Malabar Manual by William Logan

Malabar Manual by William Logan

View / download Commentary PDF digital book version.

1. COMMENTARY

CLICK HERE

2. Malabar Manual

Go back function

In a computer browser:

If you go to any other location or page by clicking on the links given here, you can come back to the previous location by keeping the Alt key on the keyboard pressed down and then pressing the Back arrow on the keyboard.

In a mobile browser:

If you go to any other location or page by clicking on the links given here, you can come back to the previous location by tapping on the Back arrow seen at the bottom of the mobile display screen.

Last edited by VED on Tue Feb 20, 2024 12:59 pm, edited 32 times in total.

Profile

0 #

William Logan's Malabar is popularly known as ‘Malabar Manual’. It is a huge book of more than 500,000 words. It might not be possible for a casual reader to imbibe all the minute bits of information from this book.

However, in this commentary of mine, I have tried to insert a lot of such bits and pieces of information, by directly quoting the lines from ‘Malabar’. On these quoted lines, I have built up a lot of arguments, and also added a lot of explanations and interpretations. I do think that it is much easy to go through my Commentary than to read the whole of William Logan's book 'Malabar'. However, the book, Malabar, contains much more items, than what this Commentary can aspire to contain.

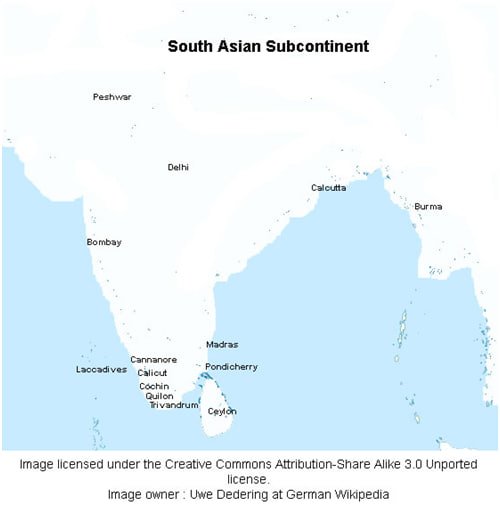

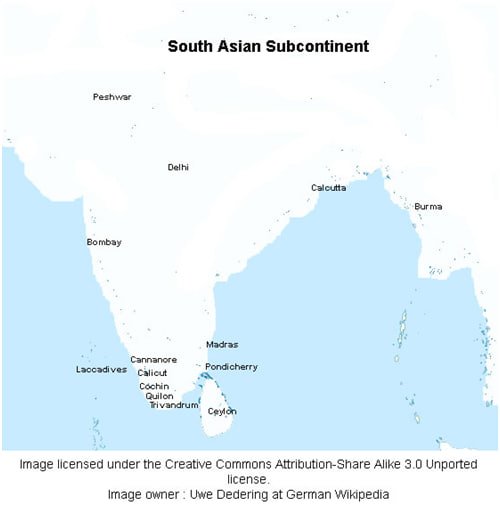

This book, Malabar, will give very detailed information on how a small group of native-Englishmen built up a great nation, by joining up extremely minute bits of barbarian and semi-barbarian geopolitical areas in the South Asian Subcontinent.

This Commentary of mine is of more than 240,000 words. I have changed the erroneous US-English spelling seen in the text, into Englander-English (English-UK). It seemed quite incongruous that an English book should have such an erroneous spelling. Maybe it is part of the doctoring done around 1950.

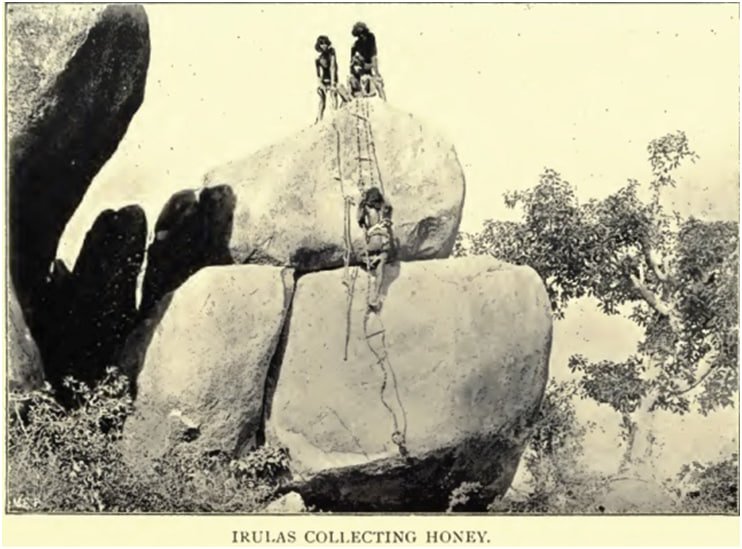

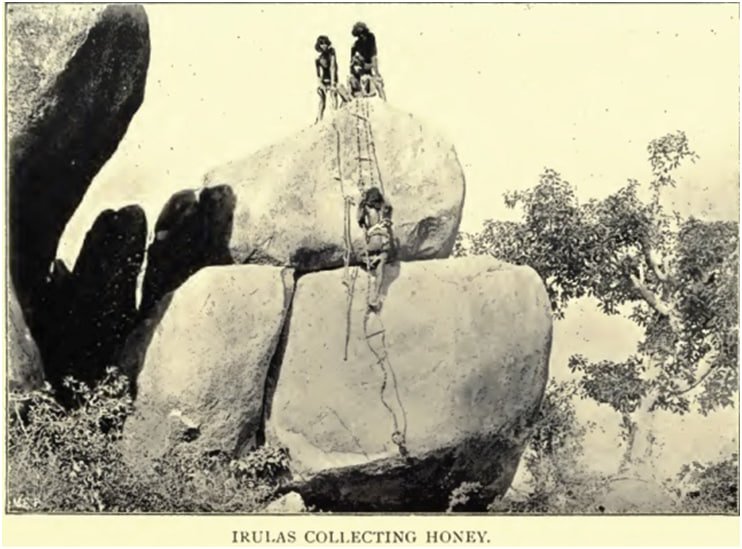

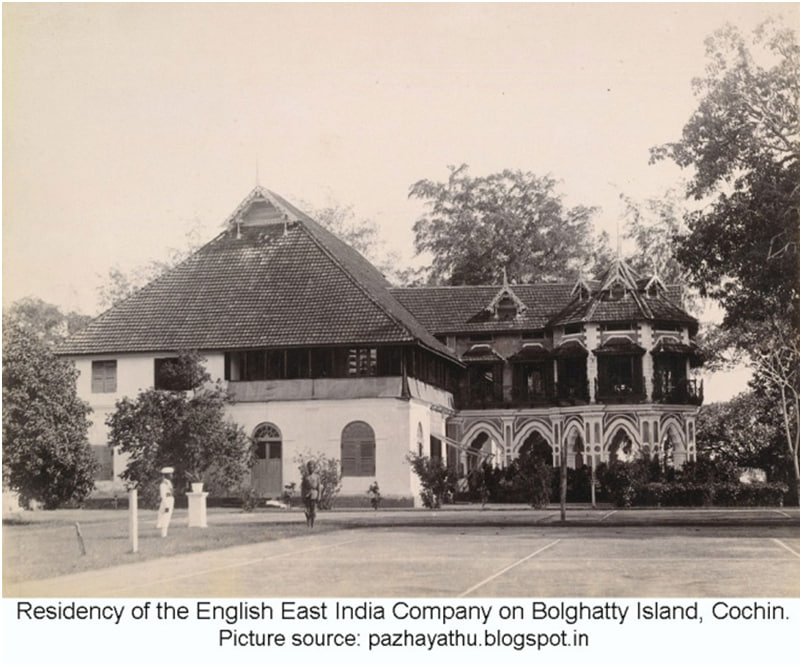

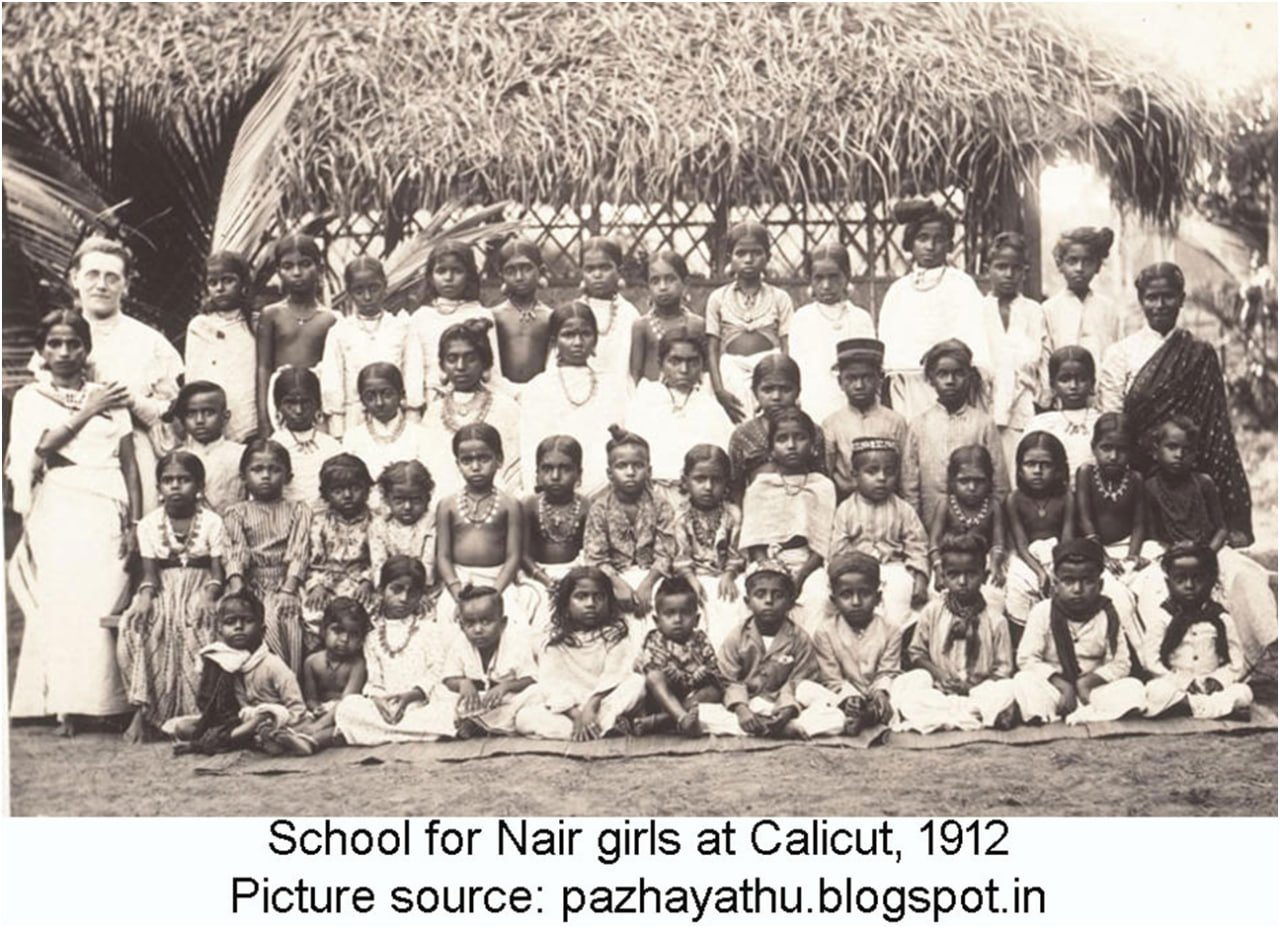

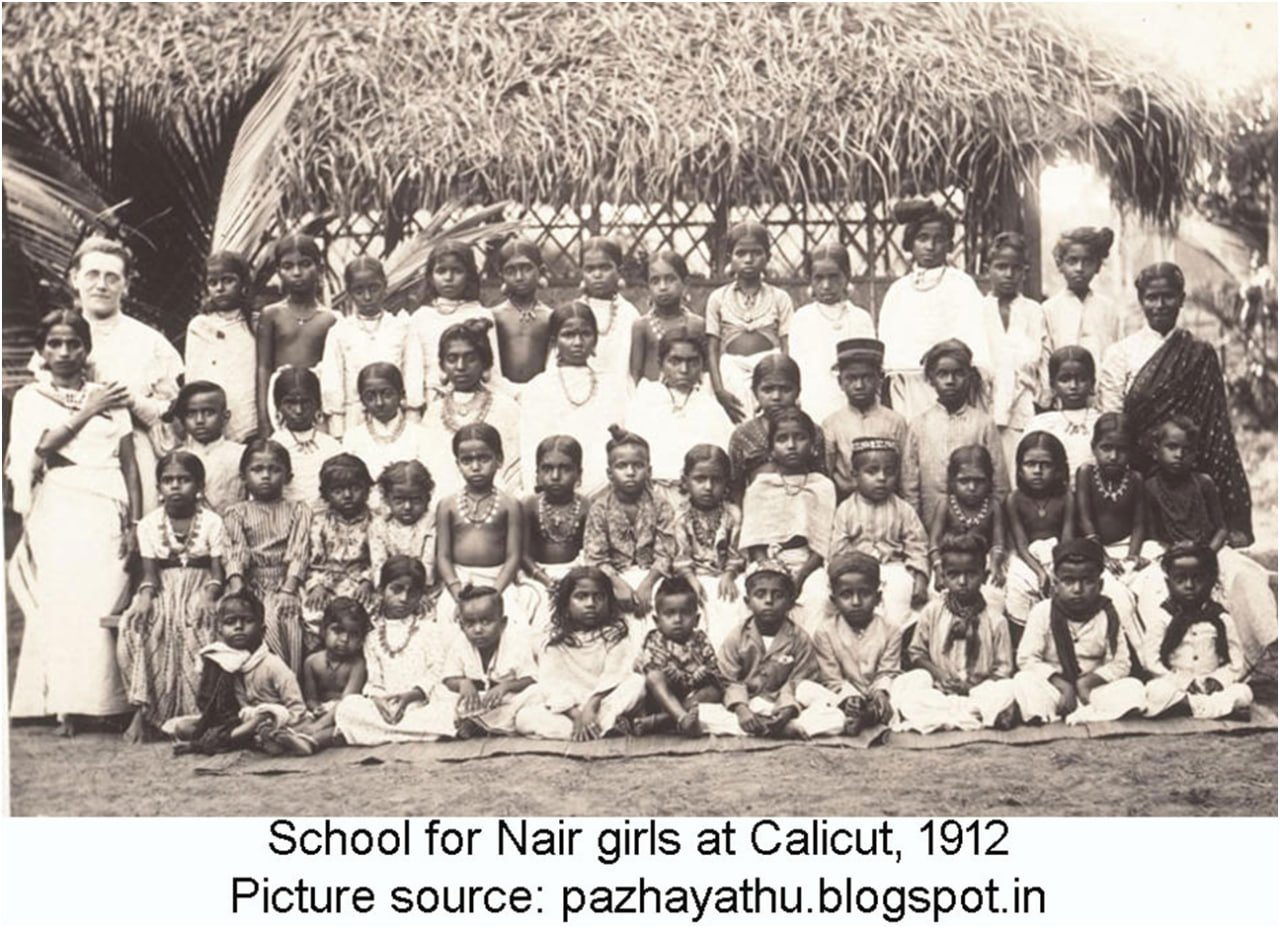

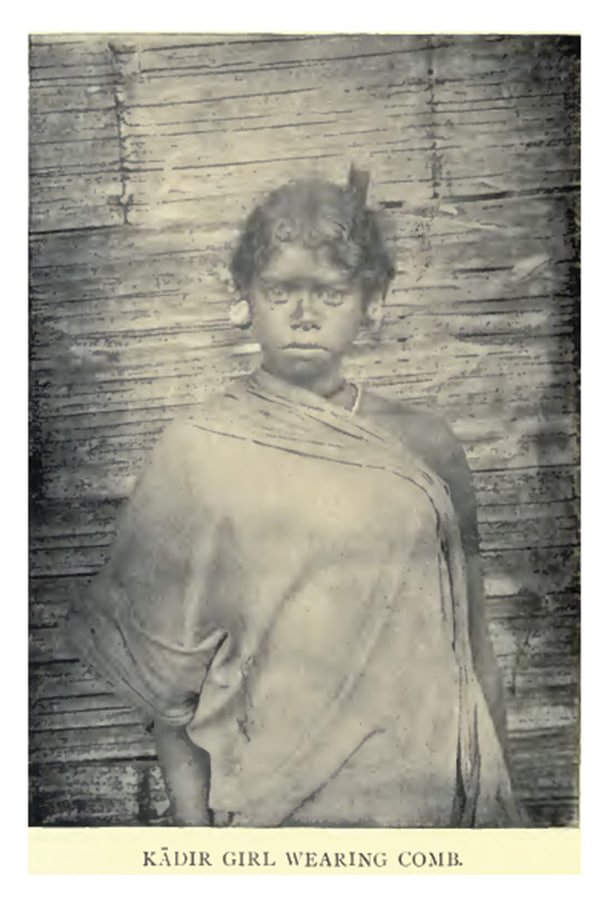

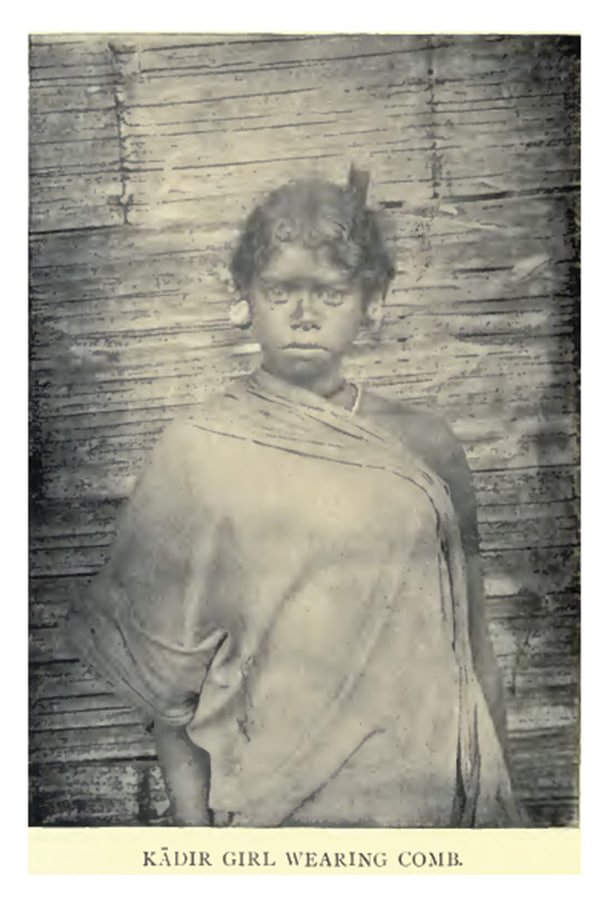

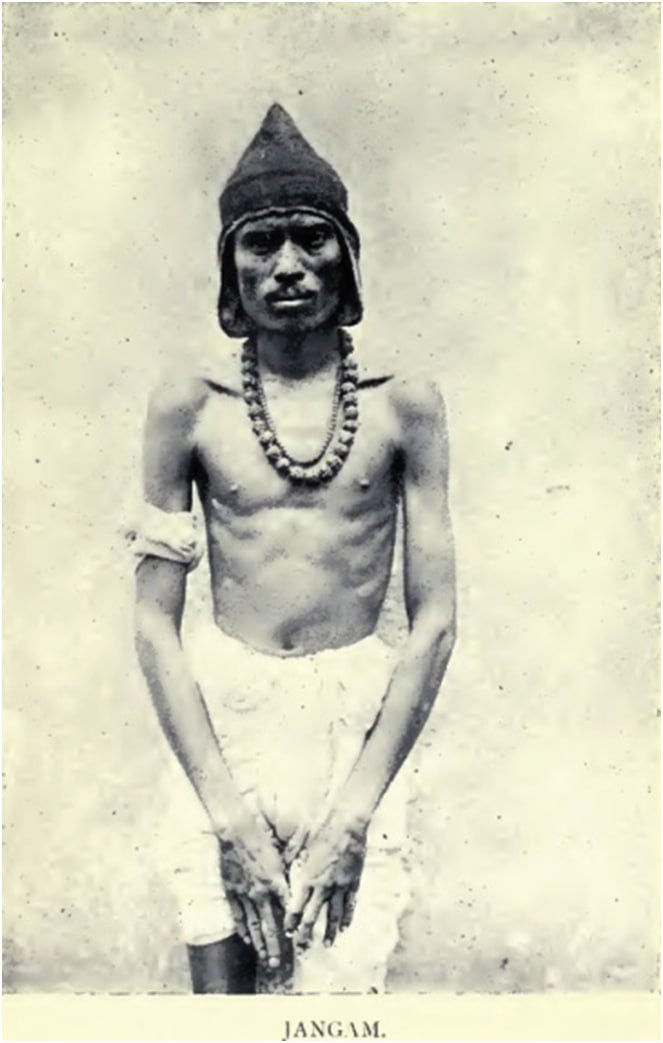

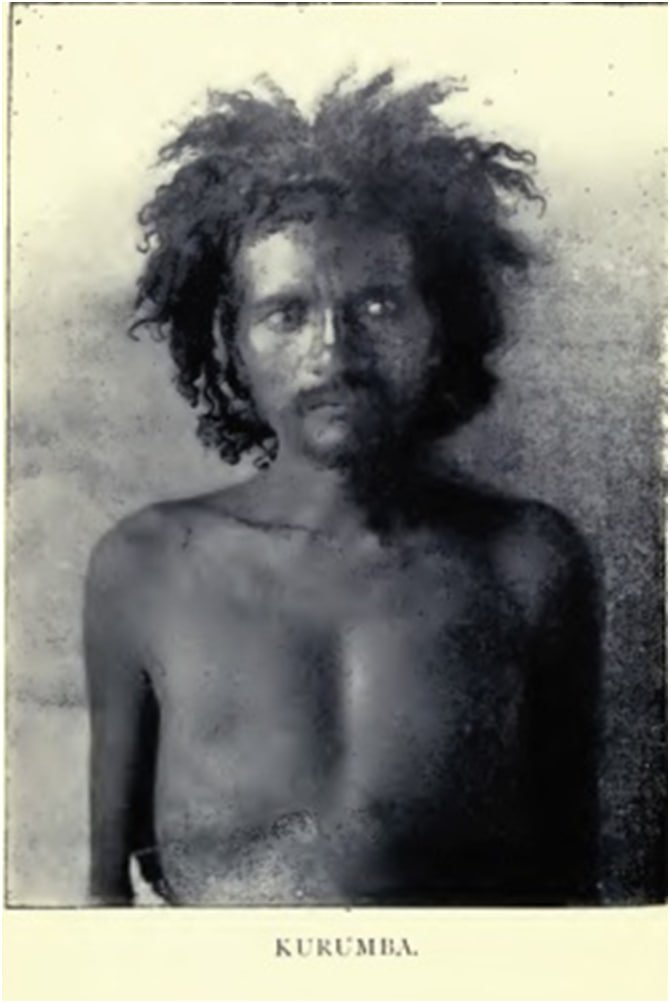

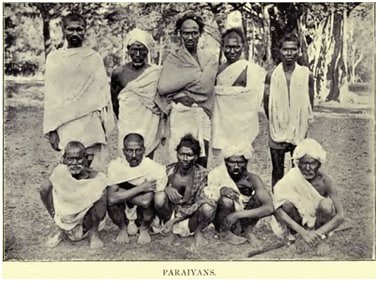

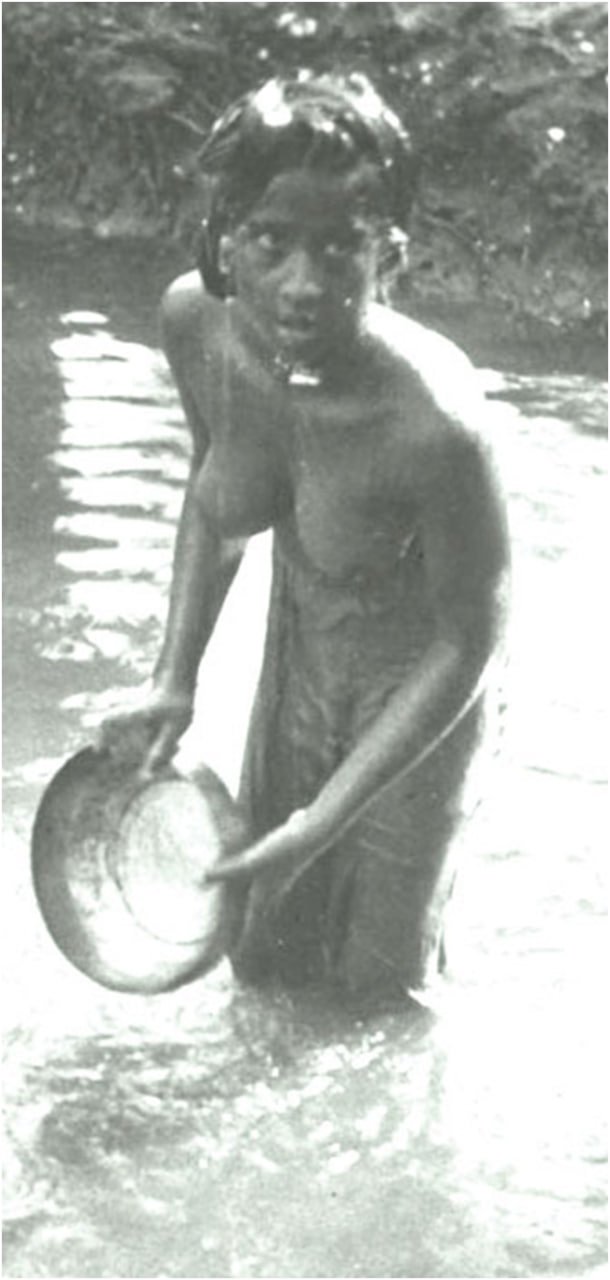

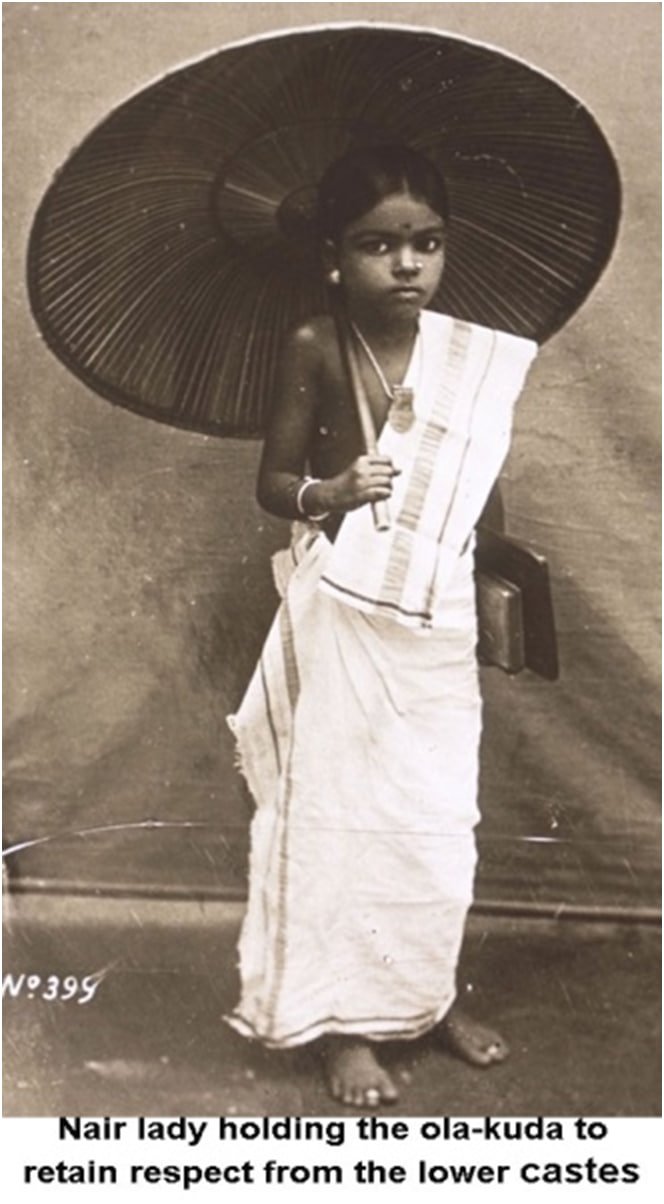

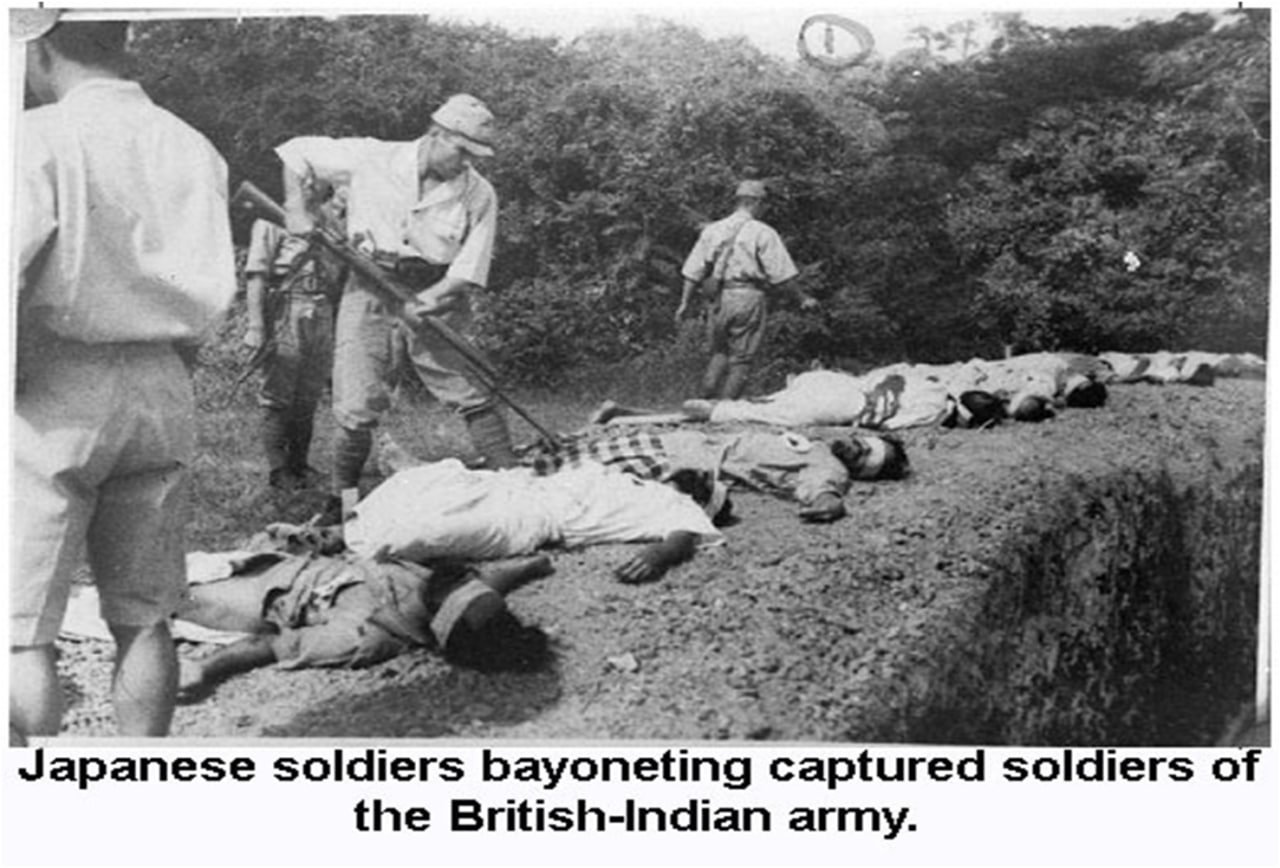

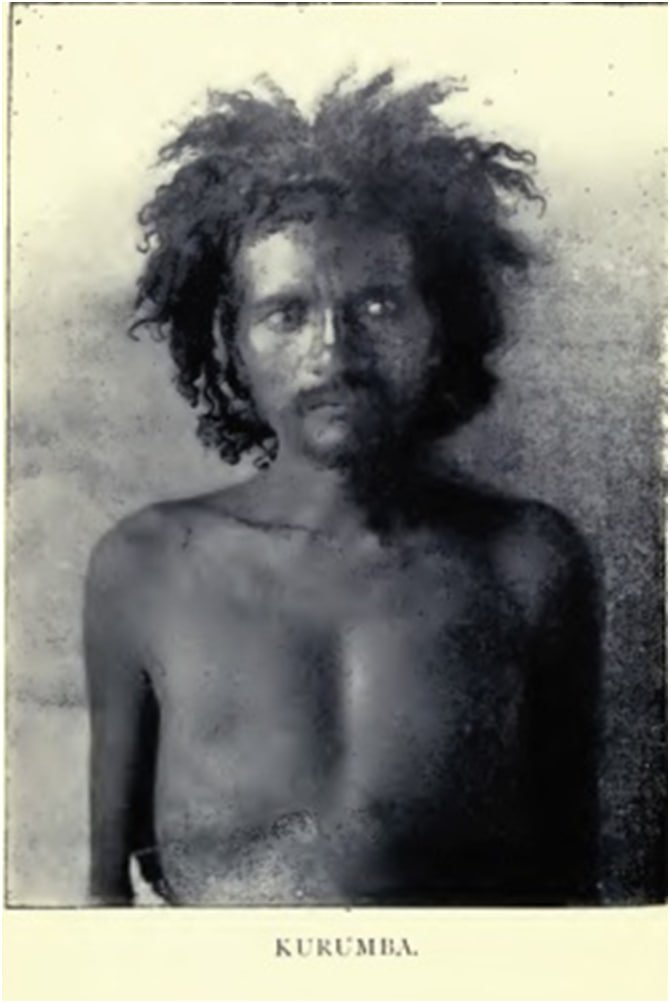

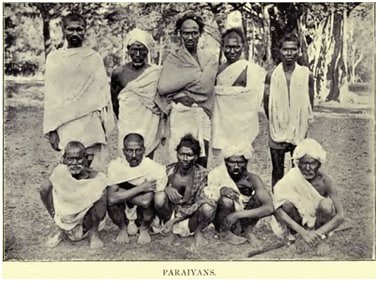

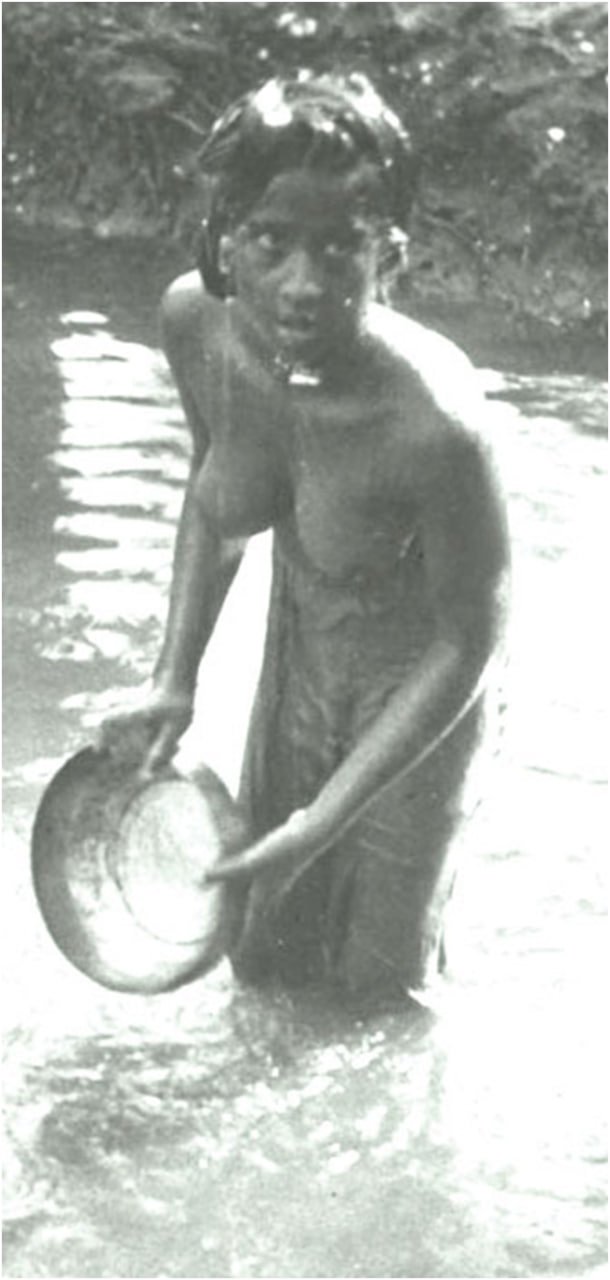

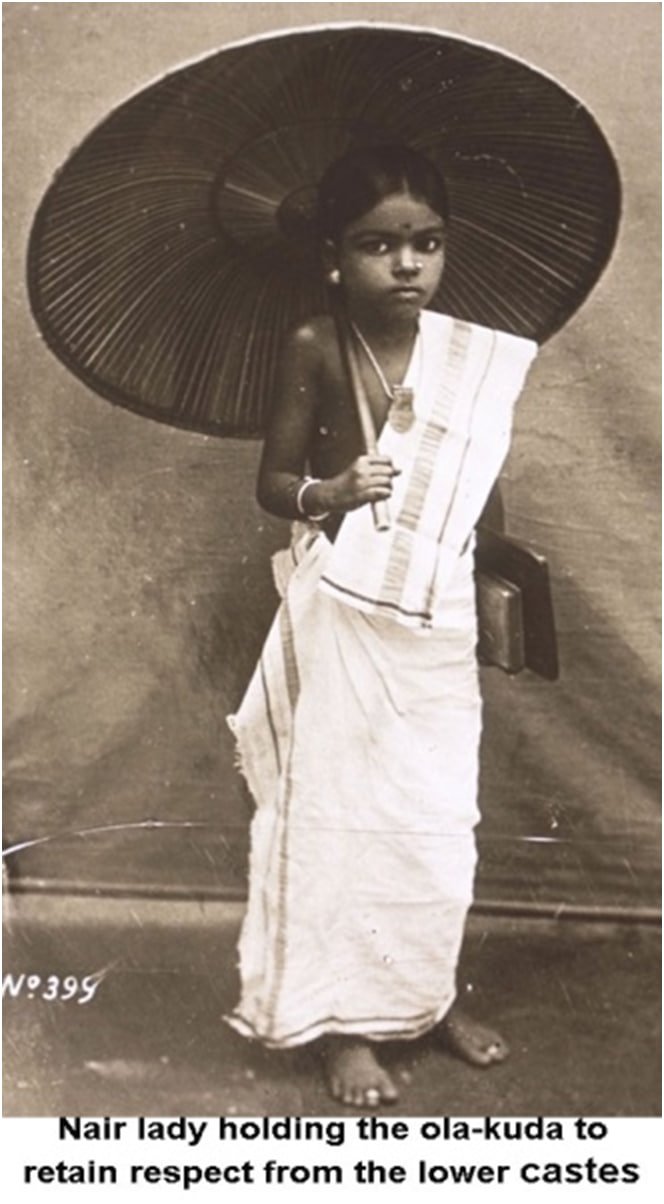

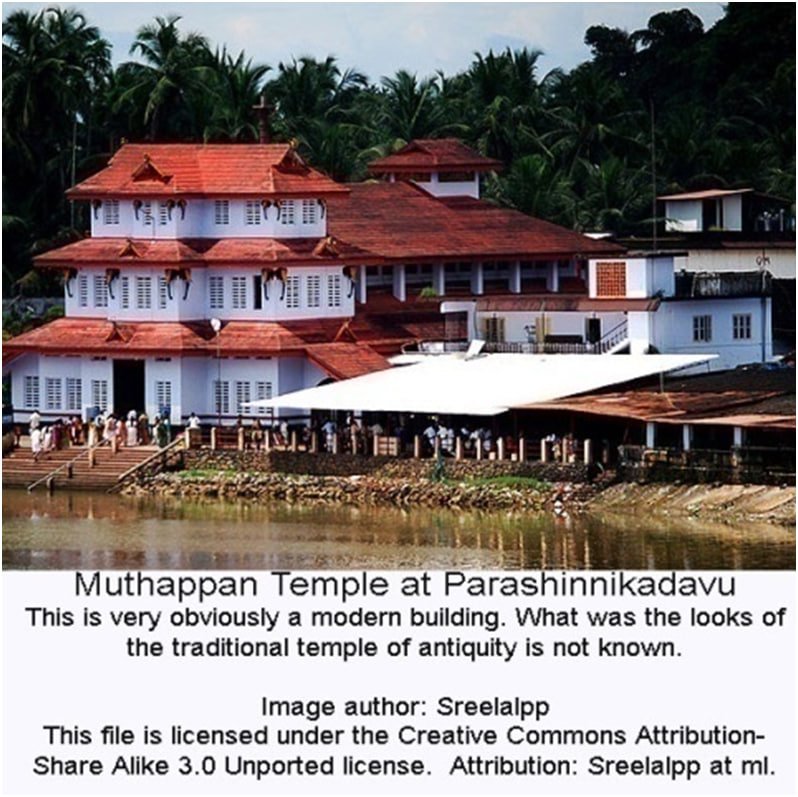

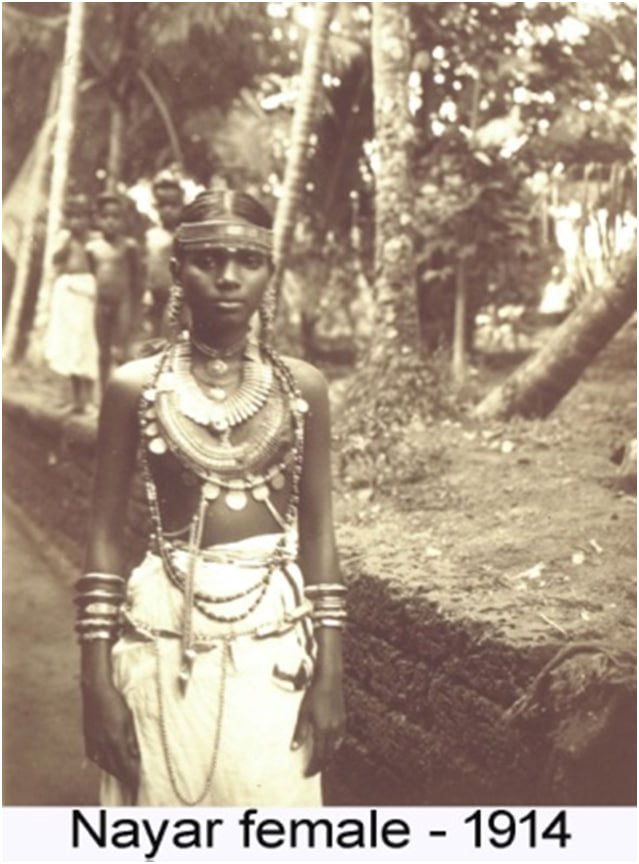

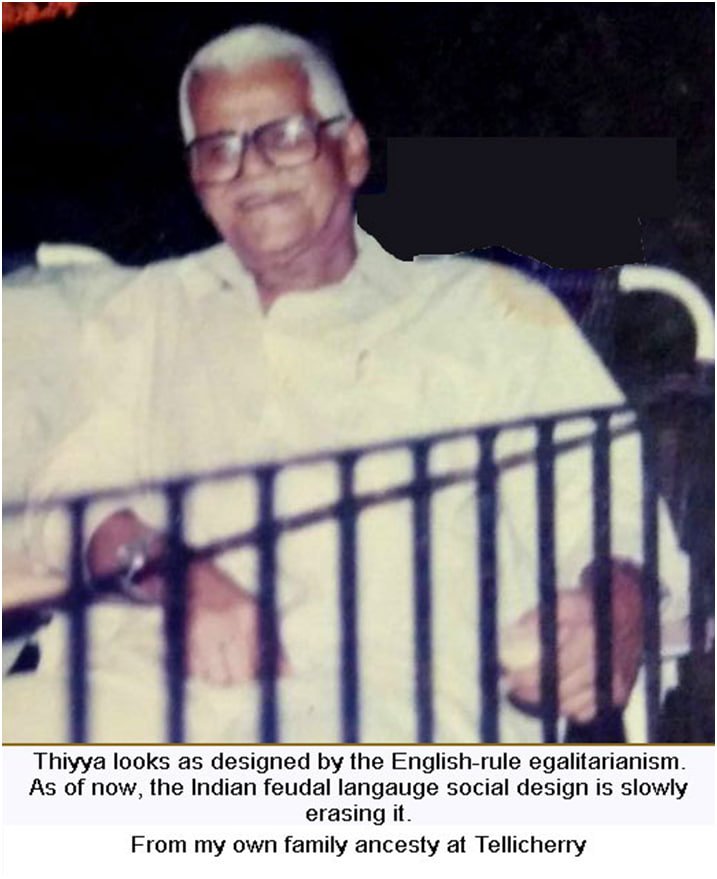

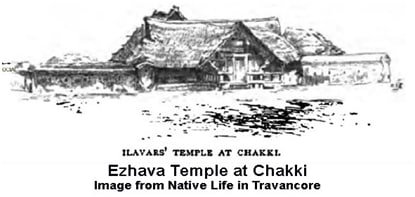

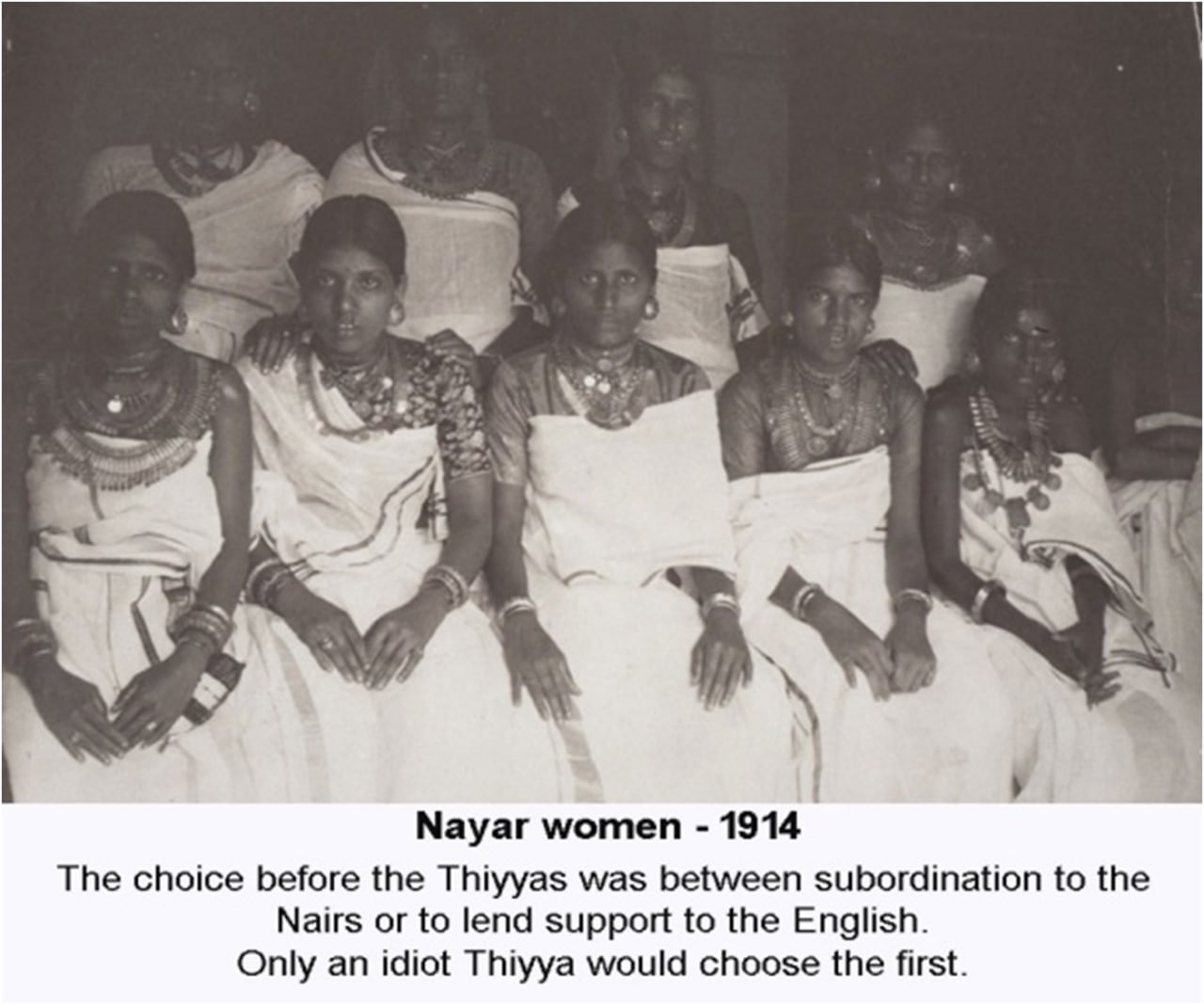

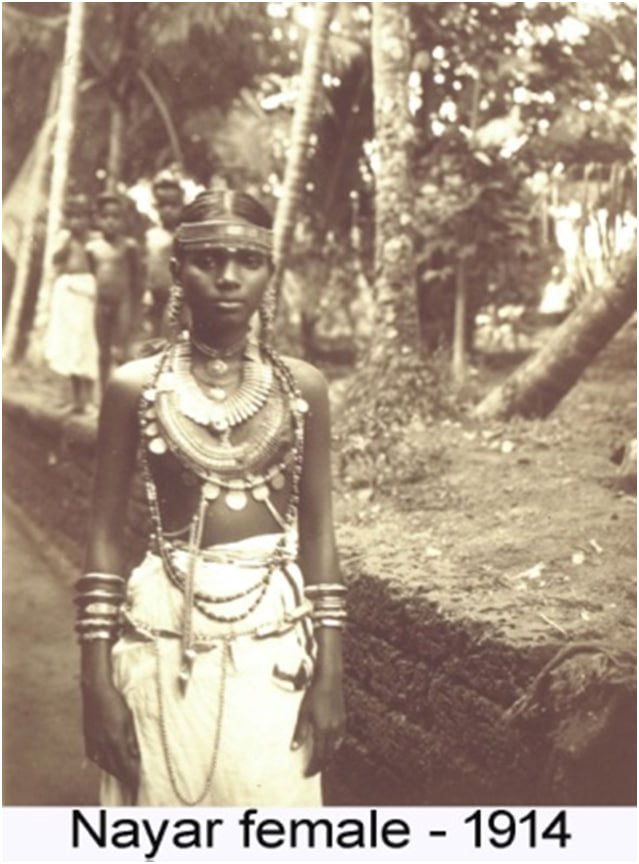

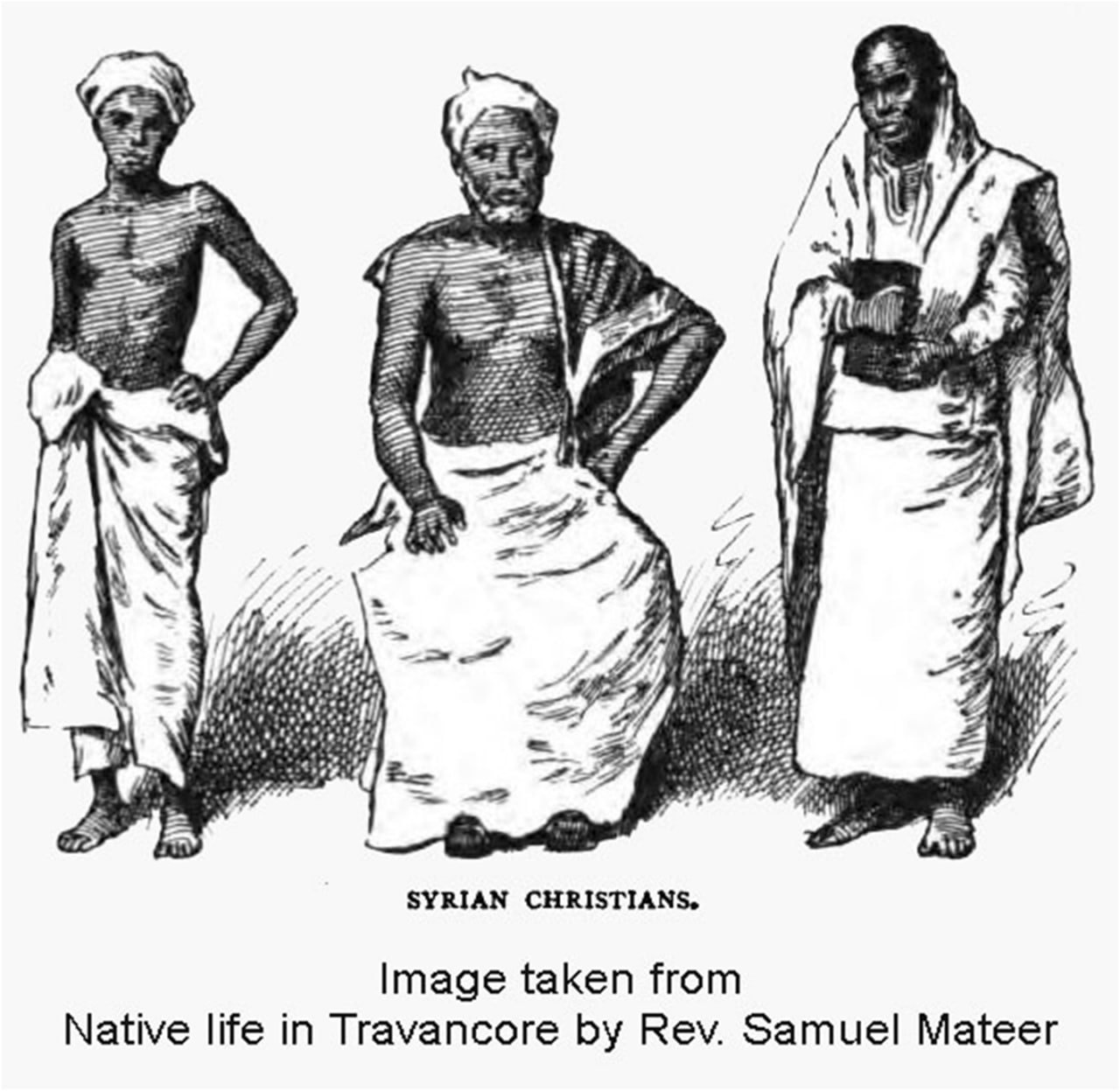

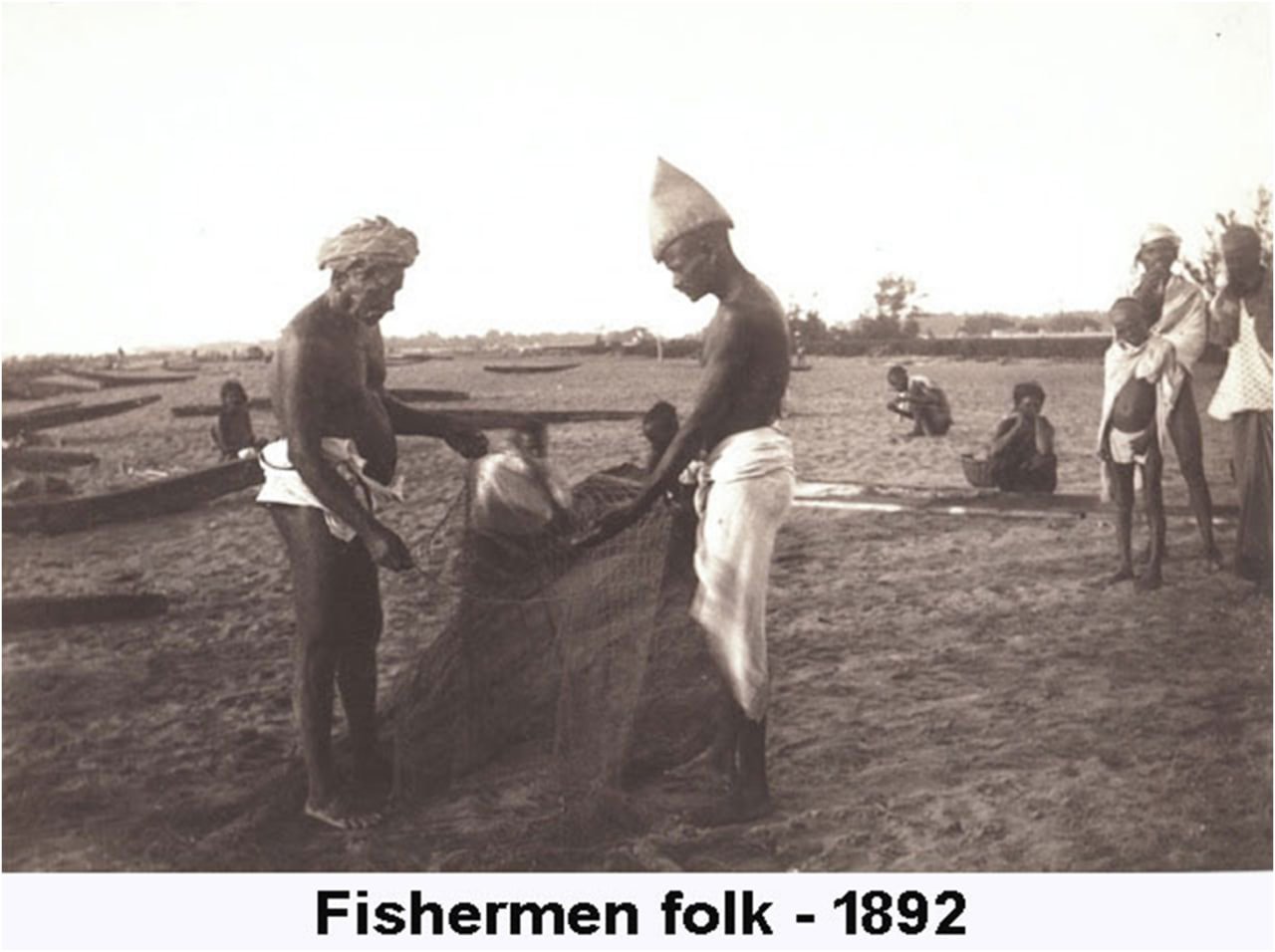

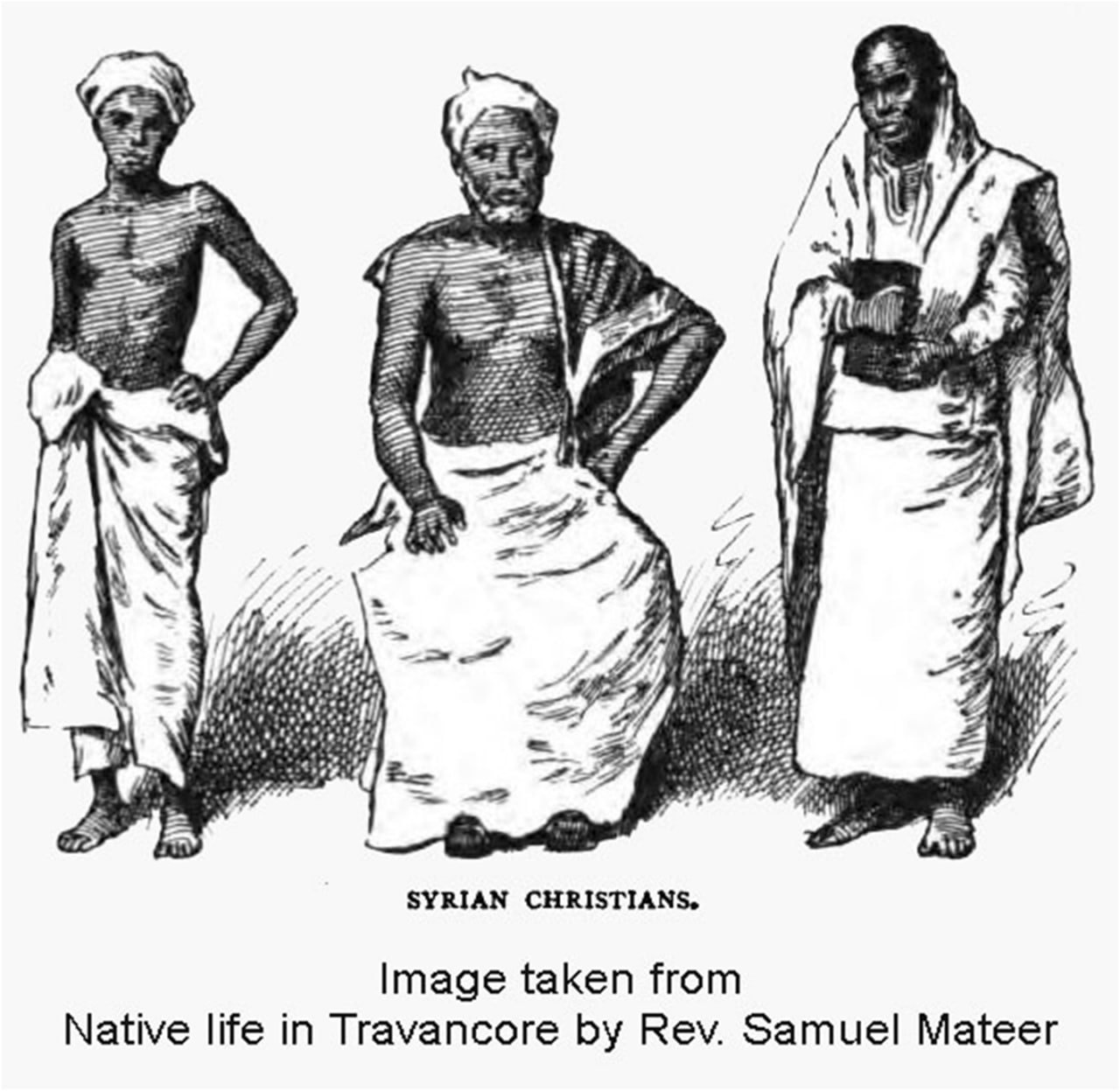

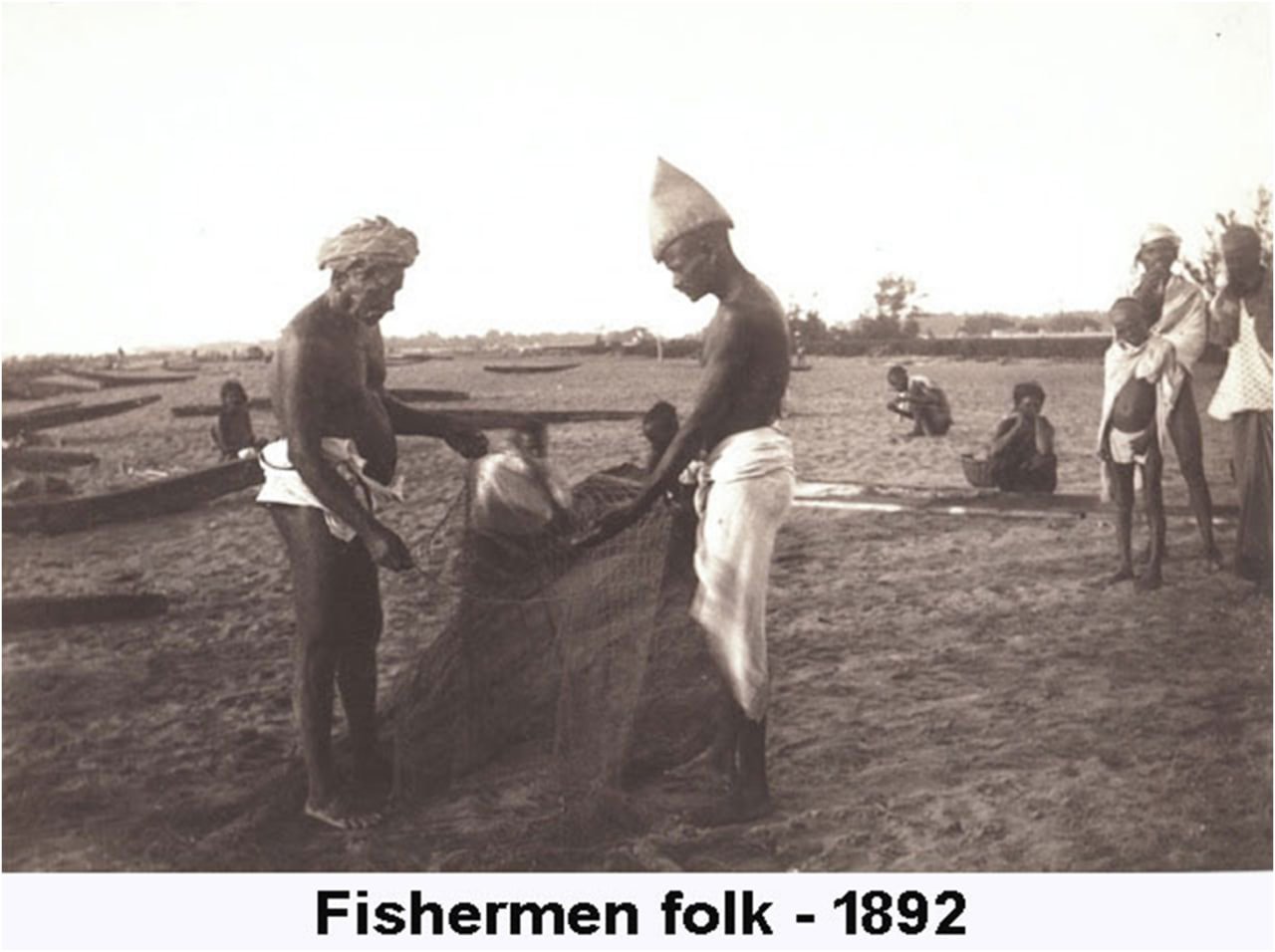

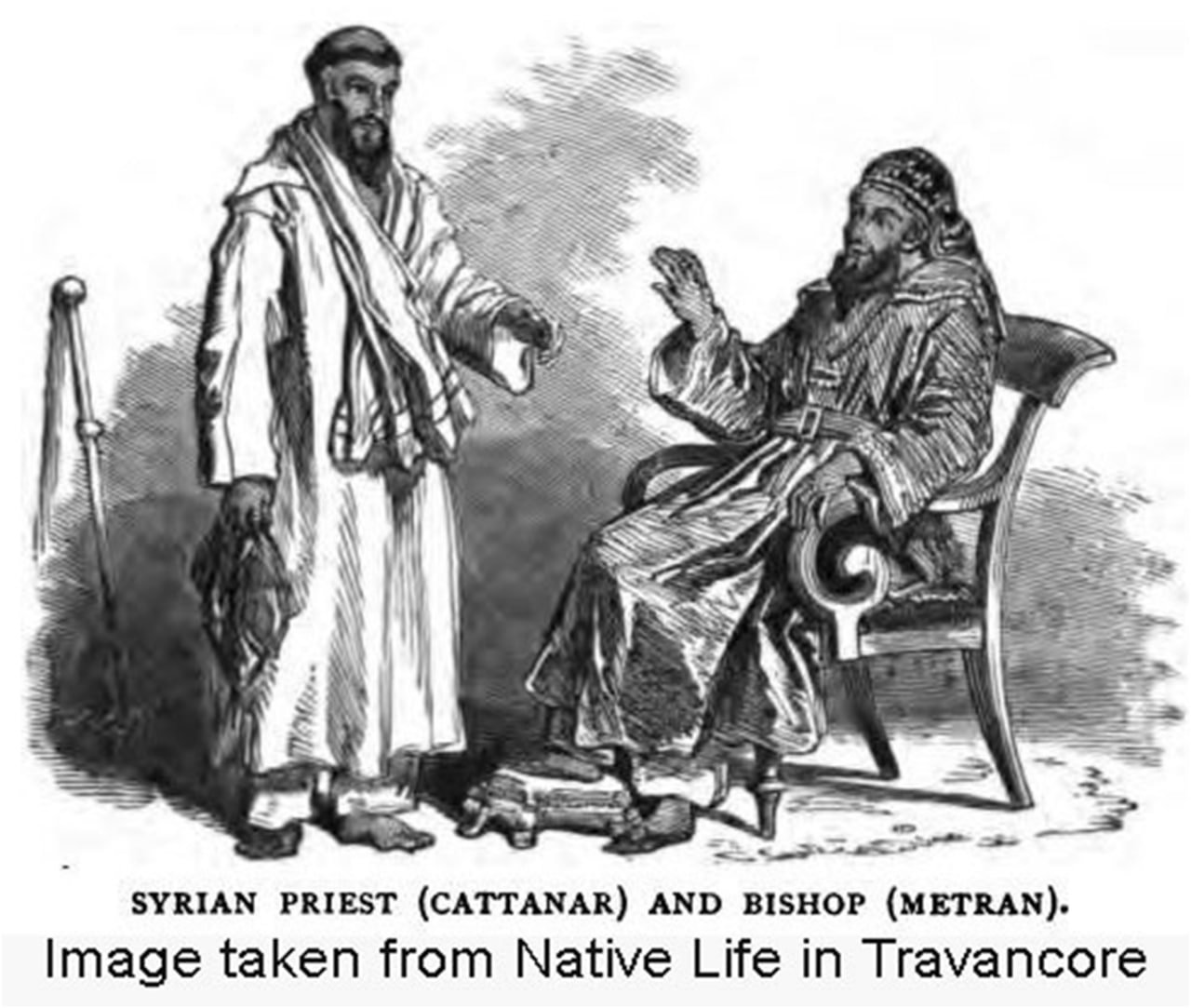

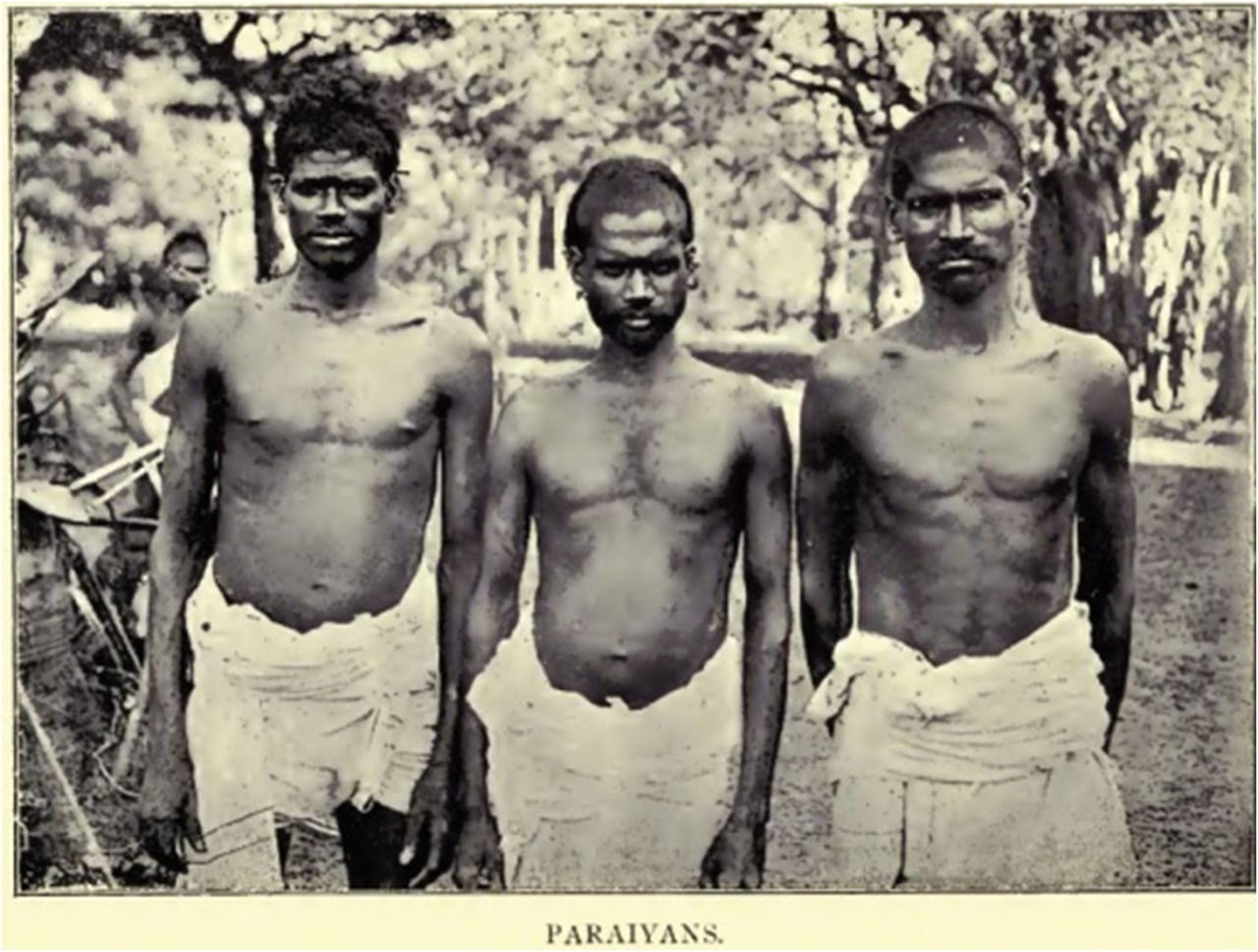

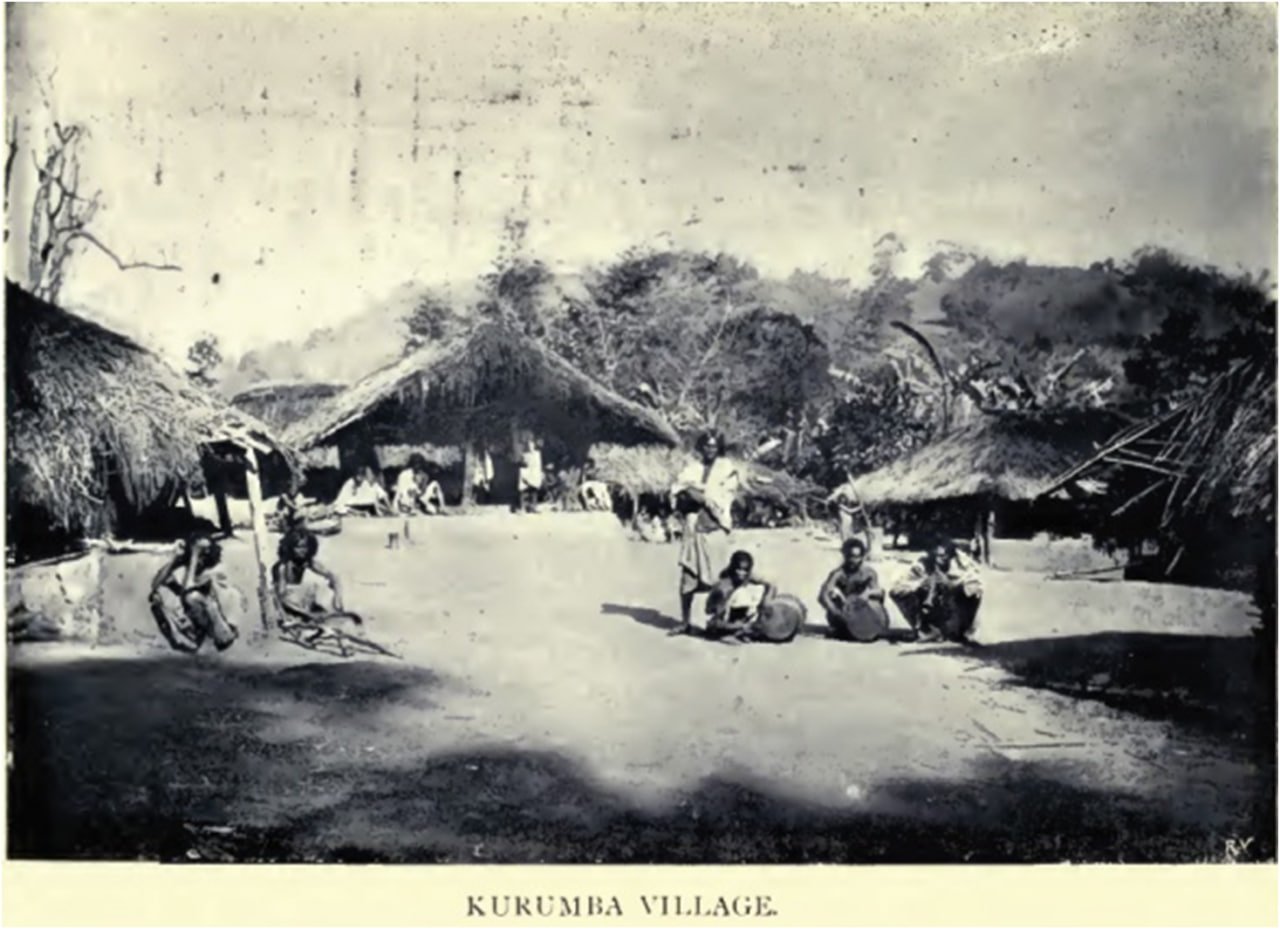

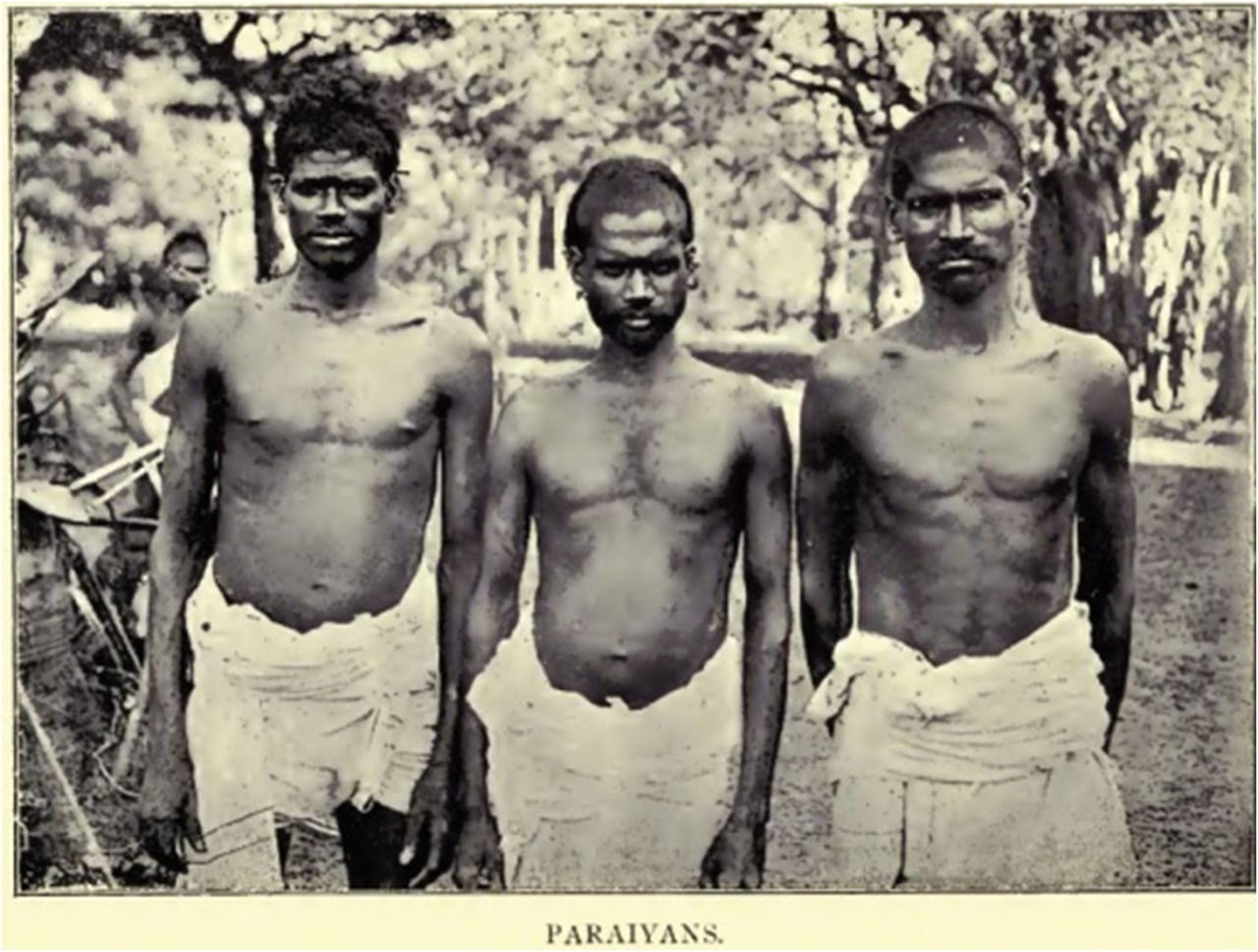

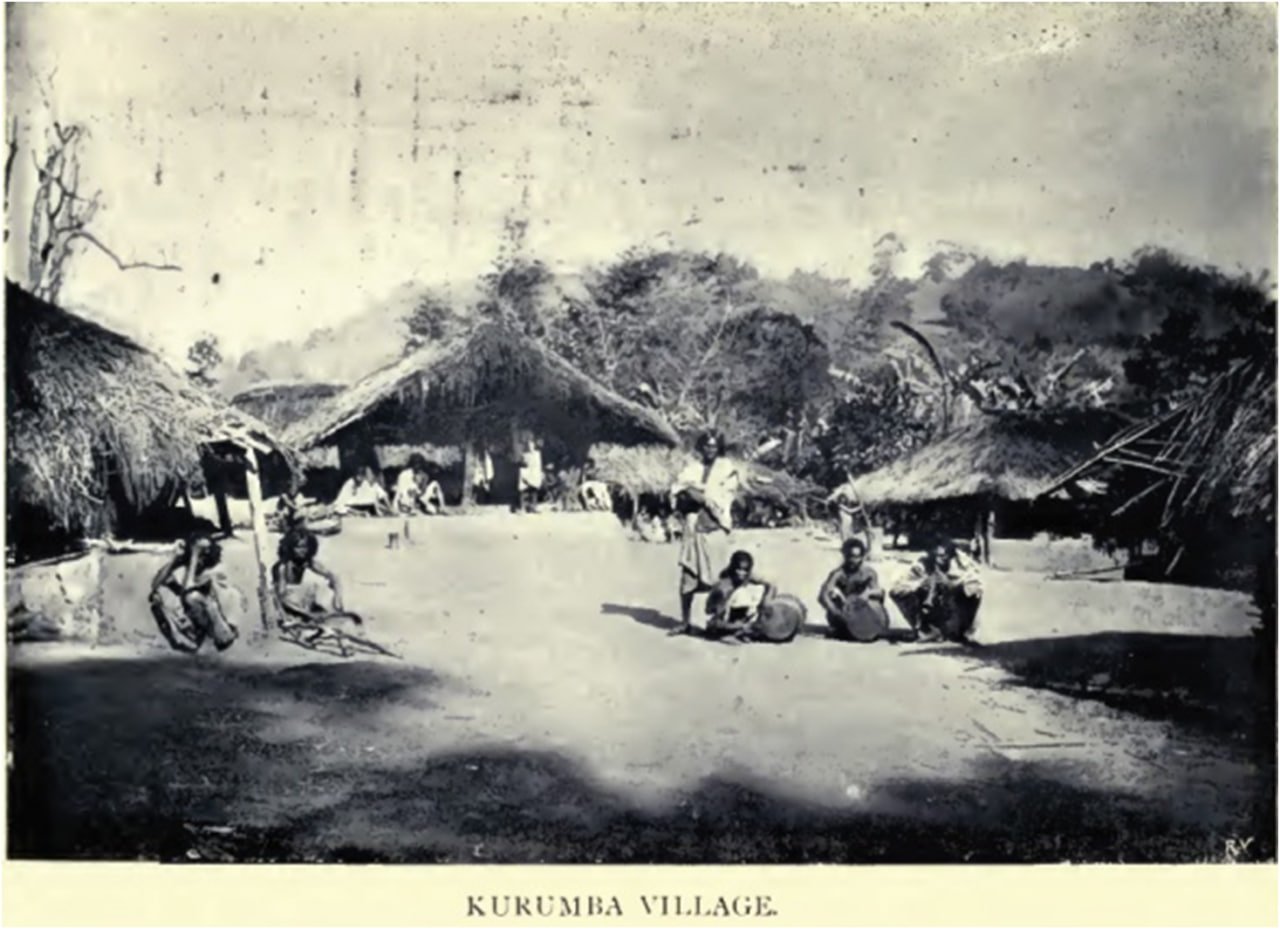

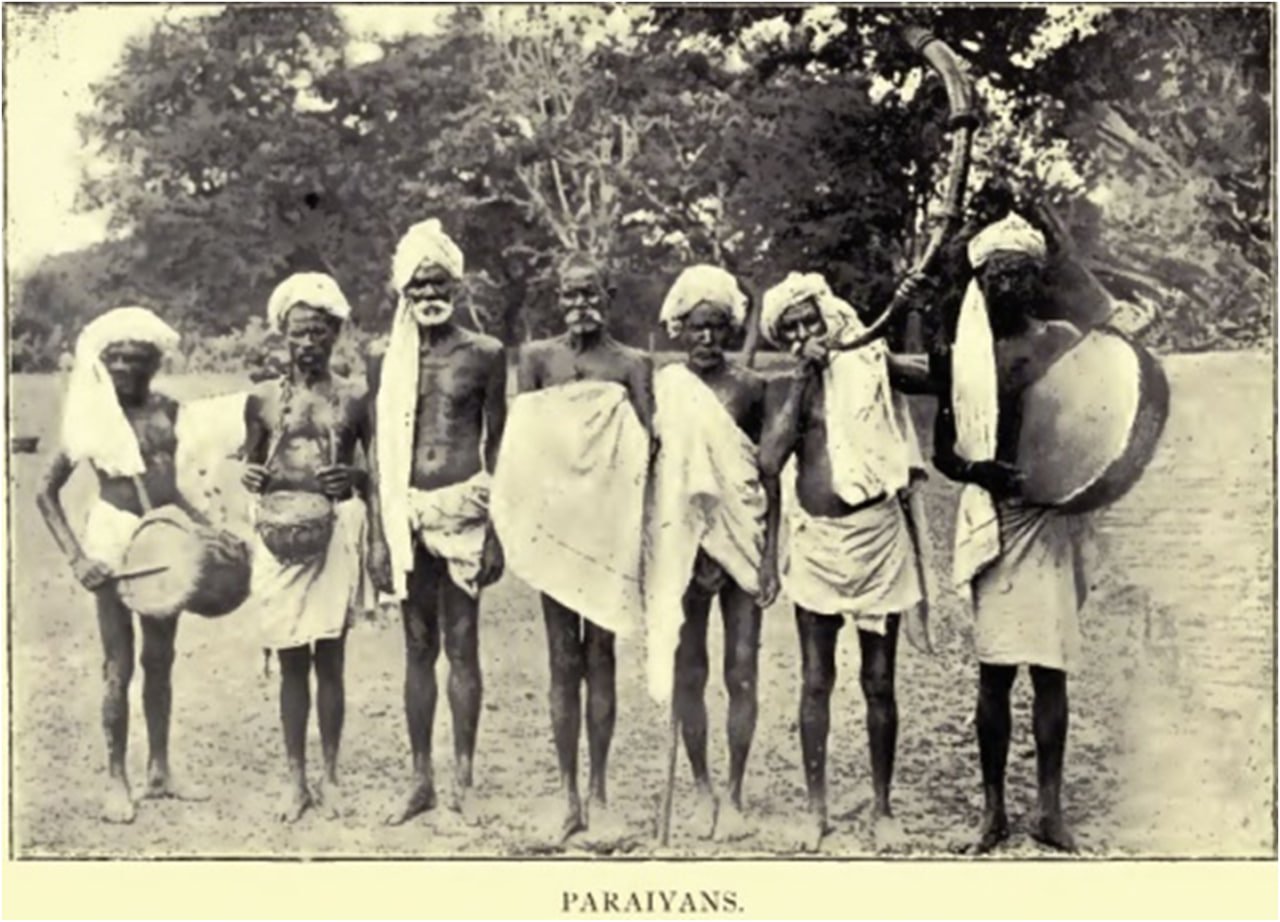

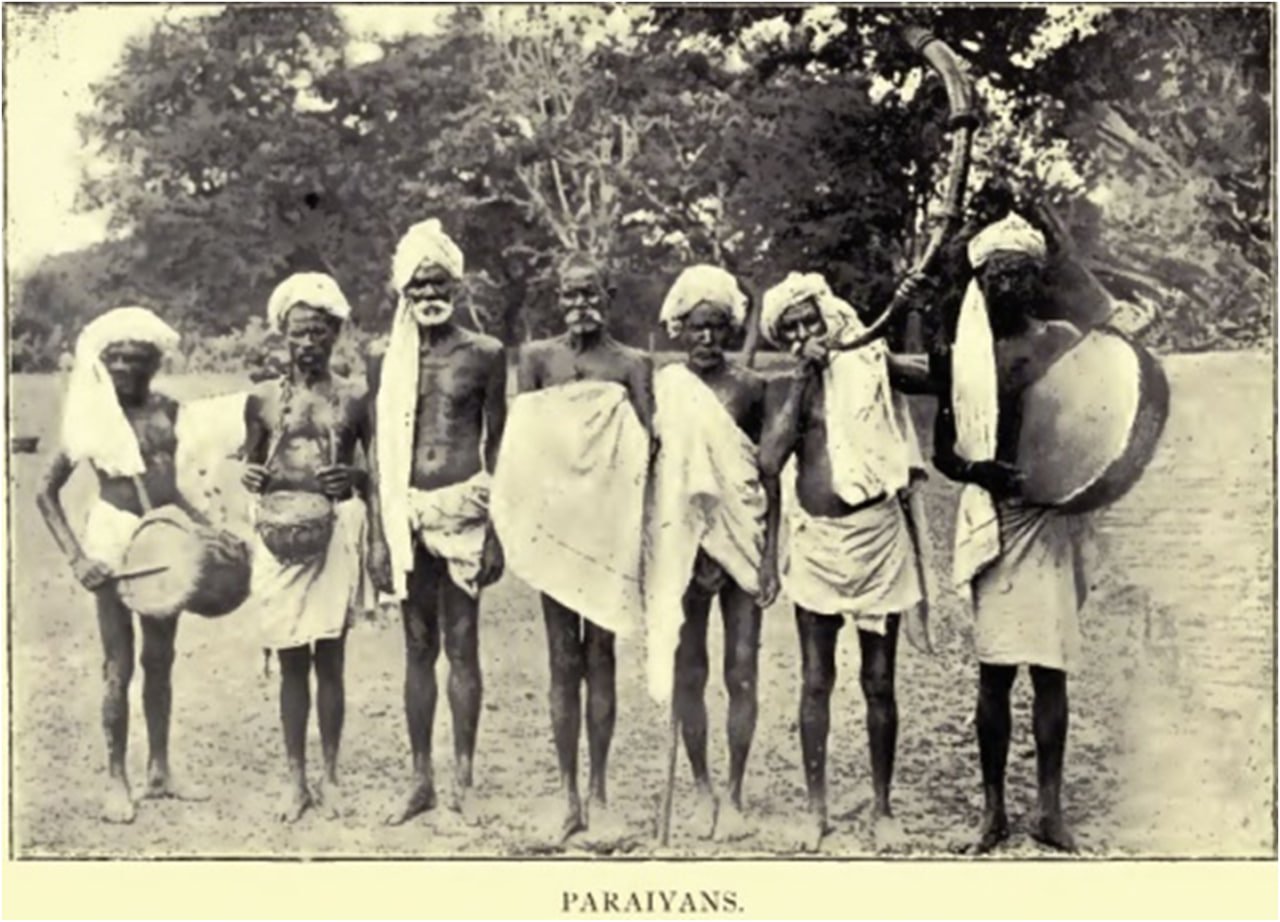

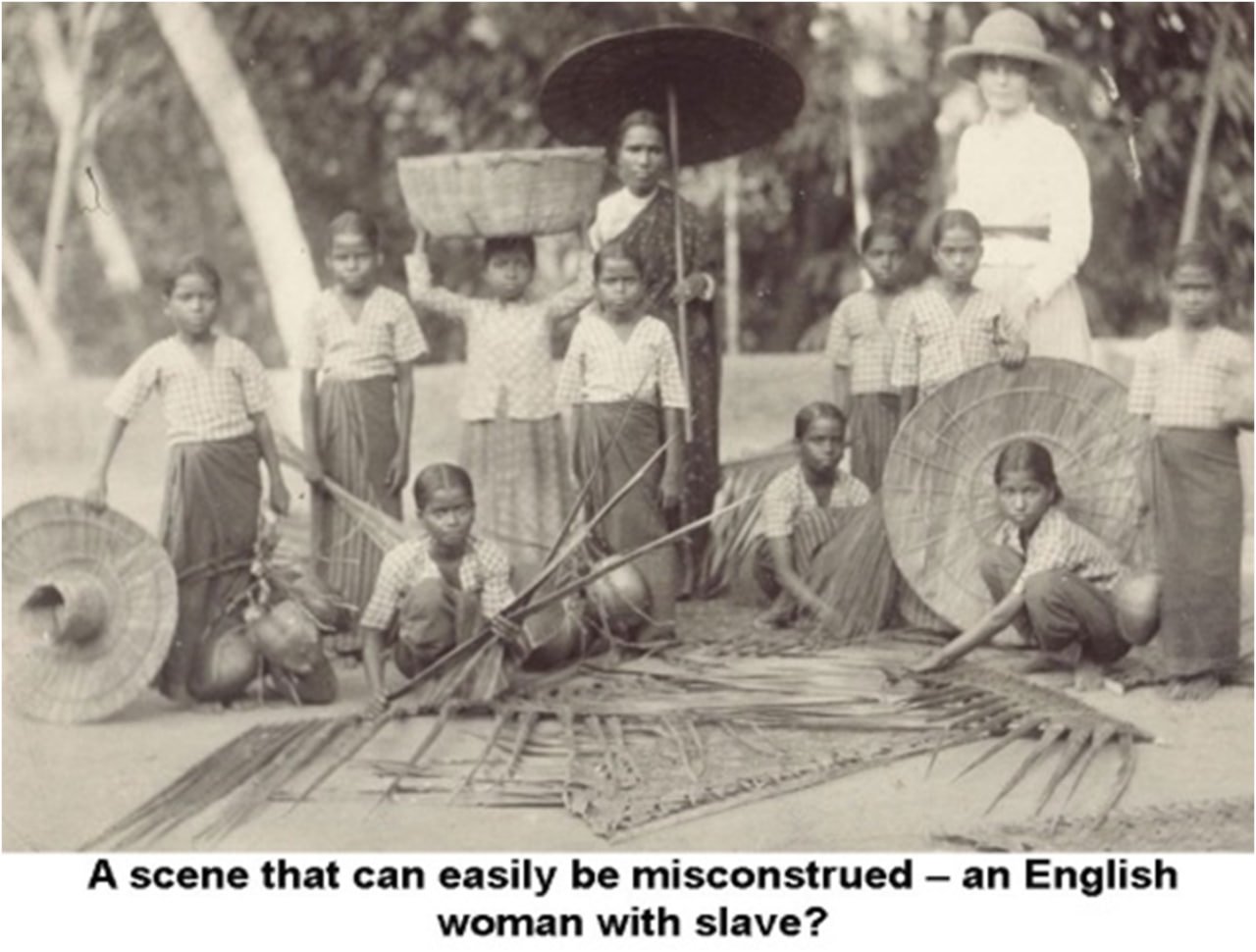

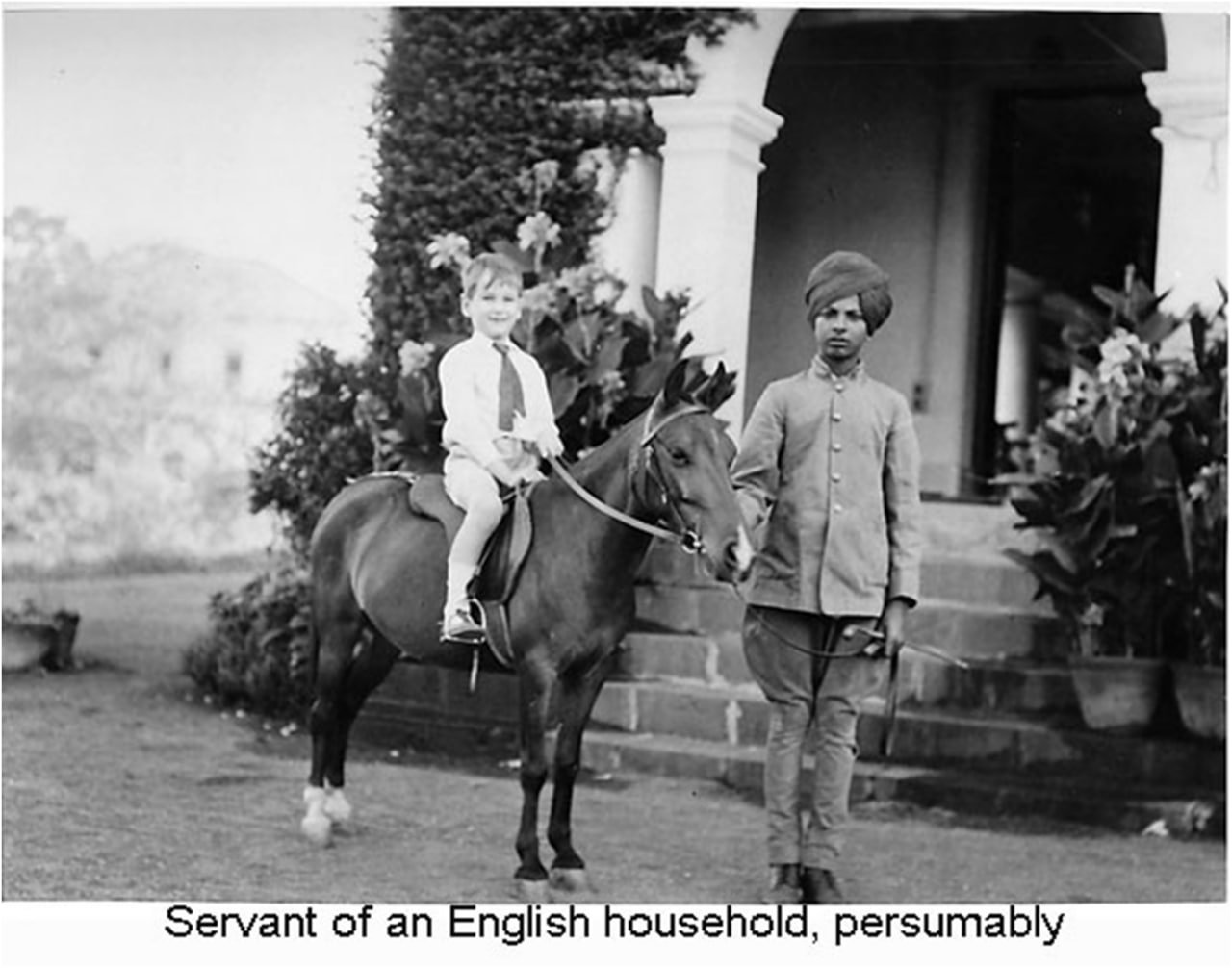

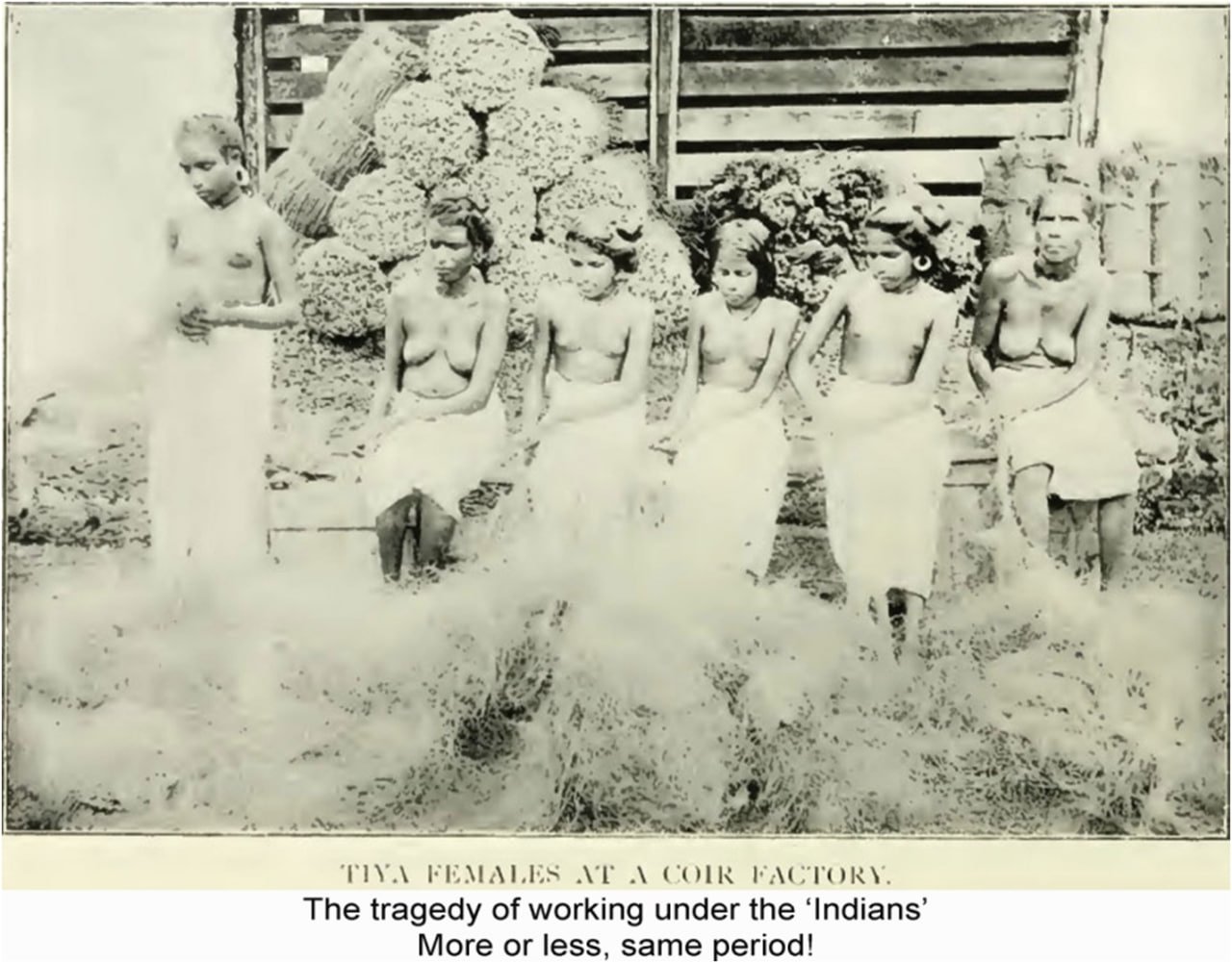

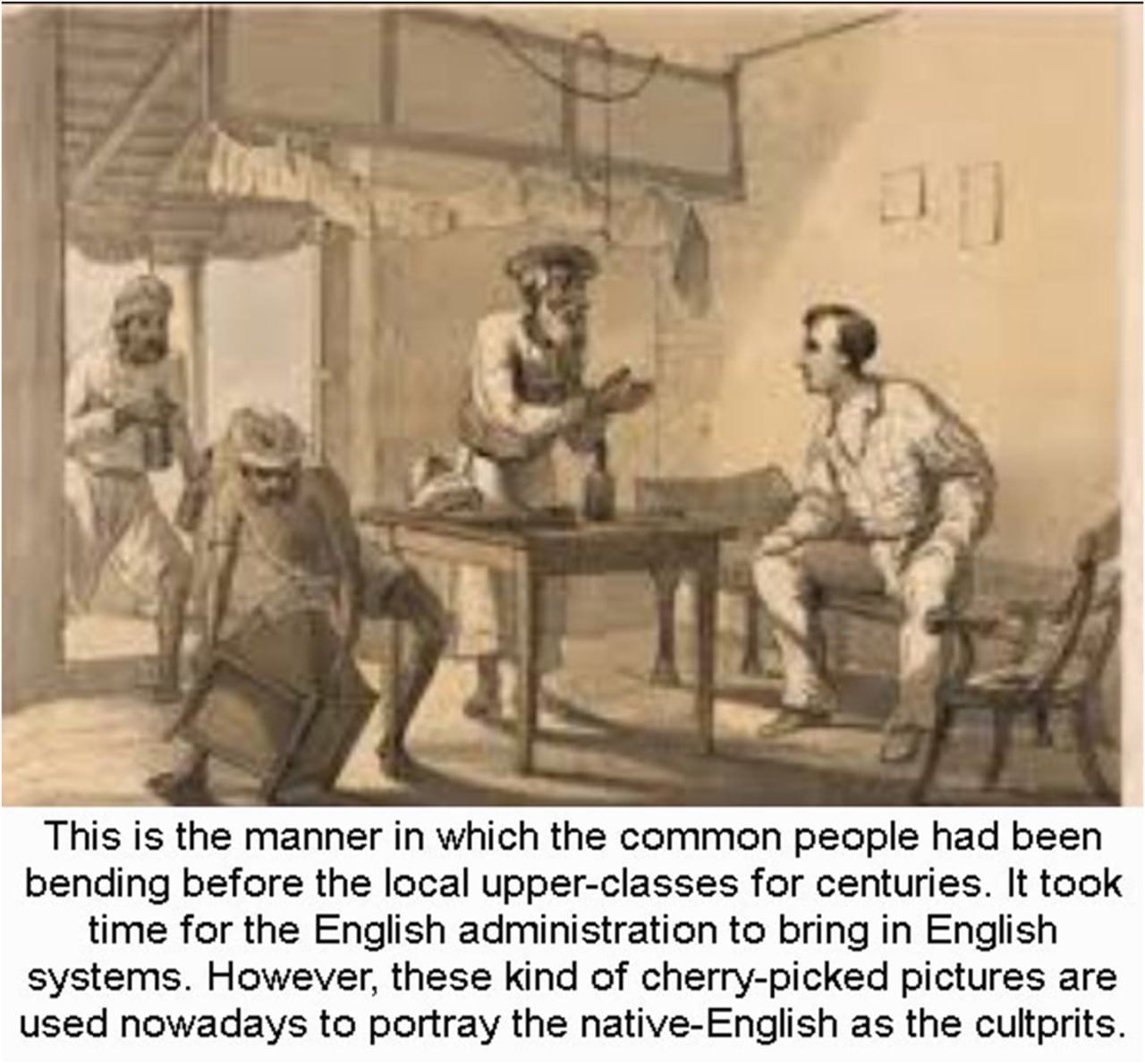

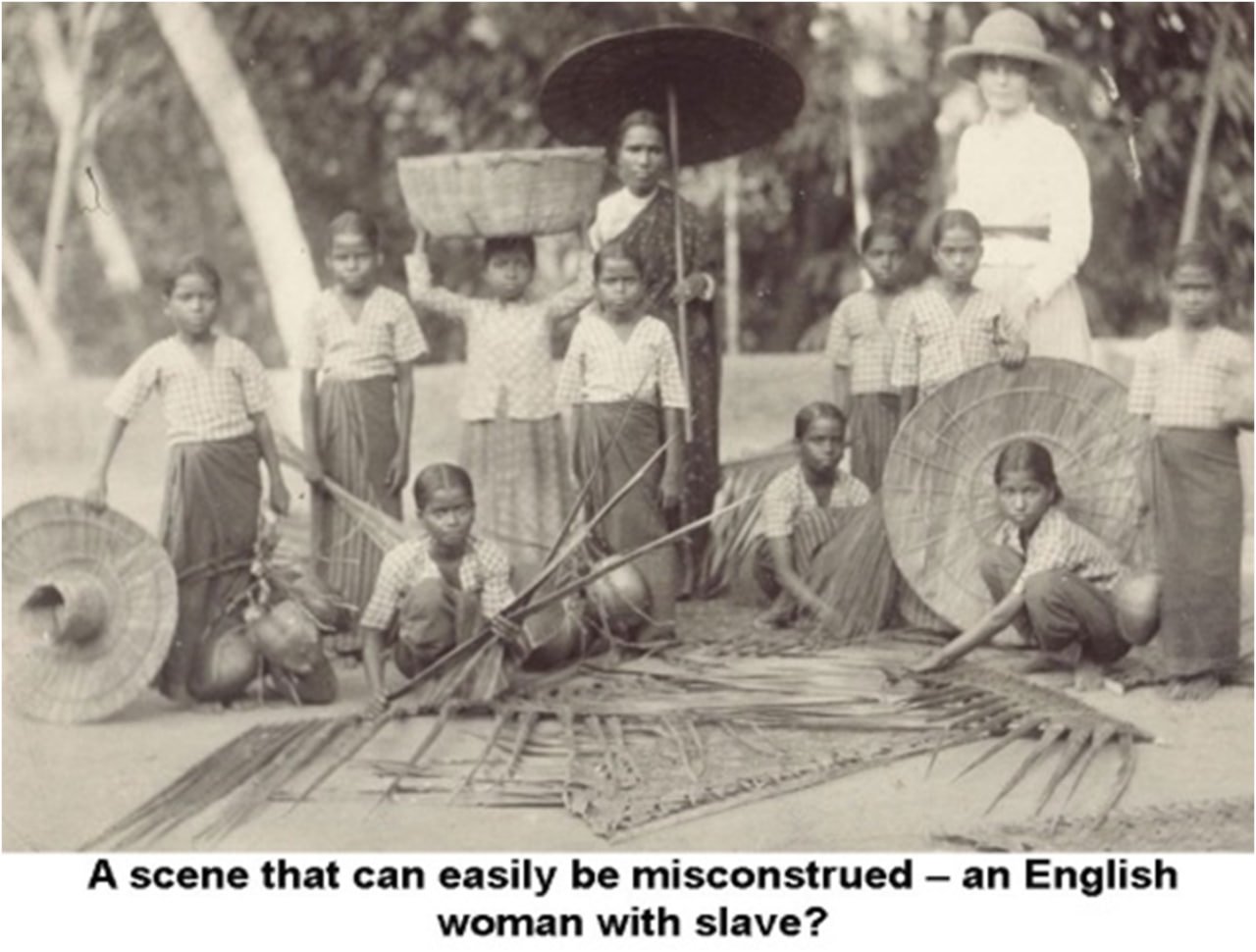

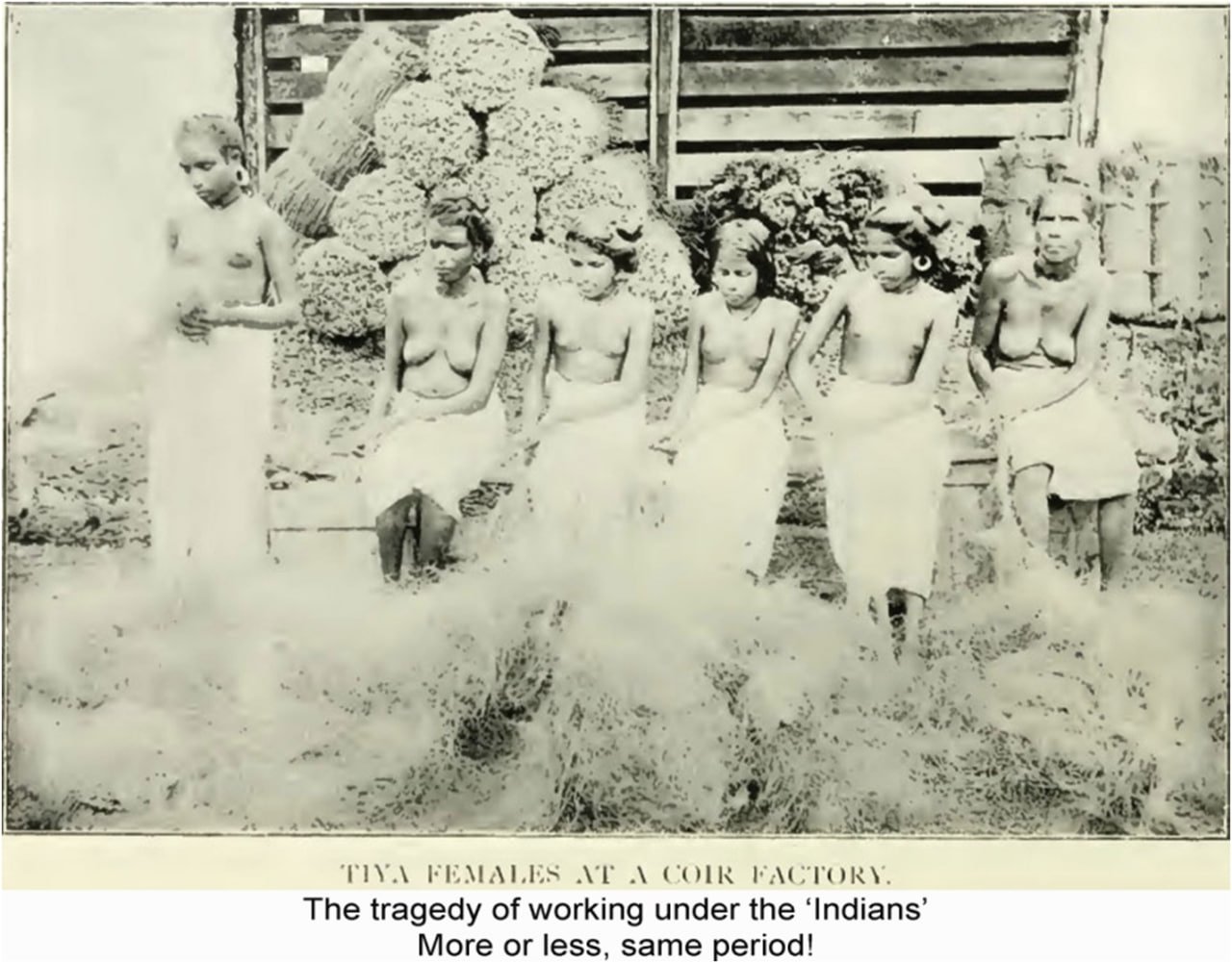

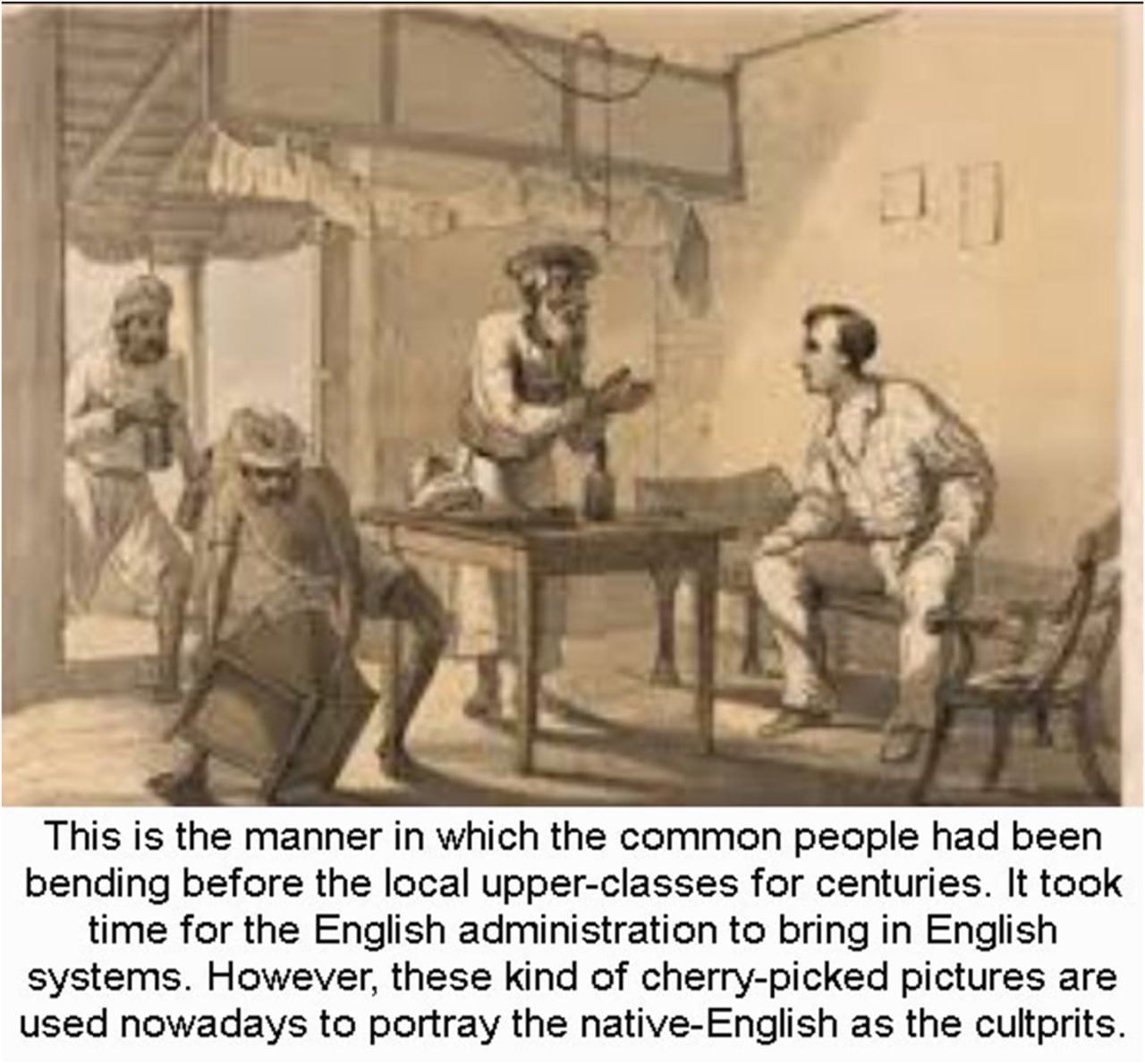

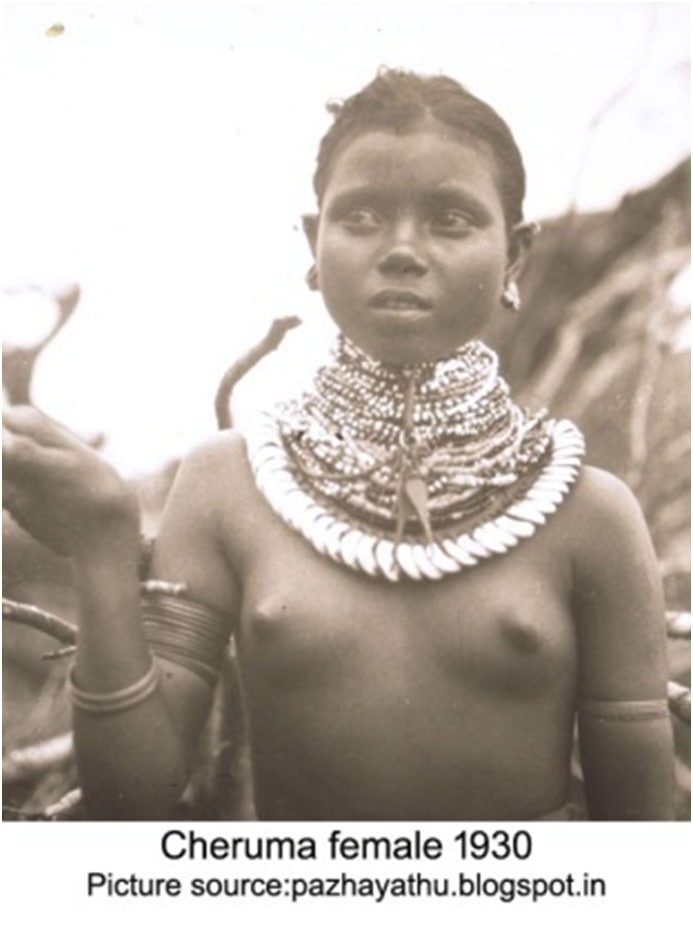

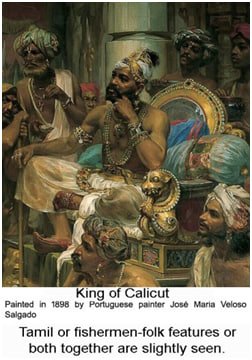

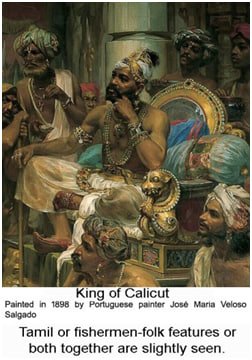

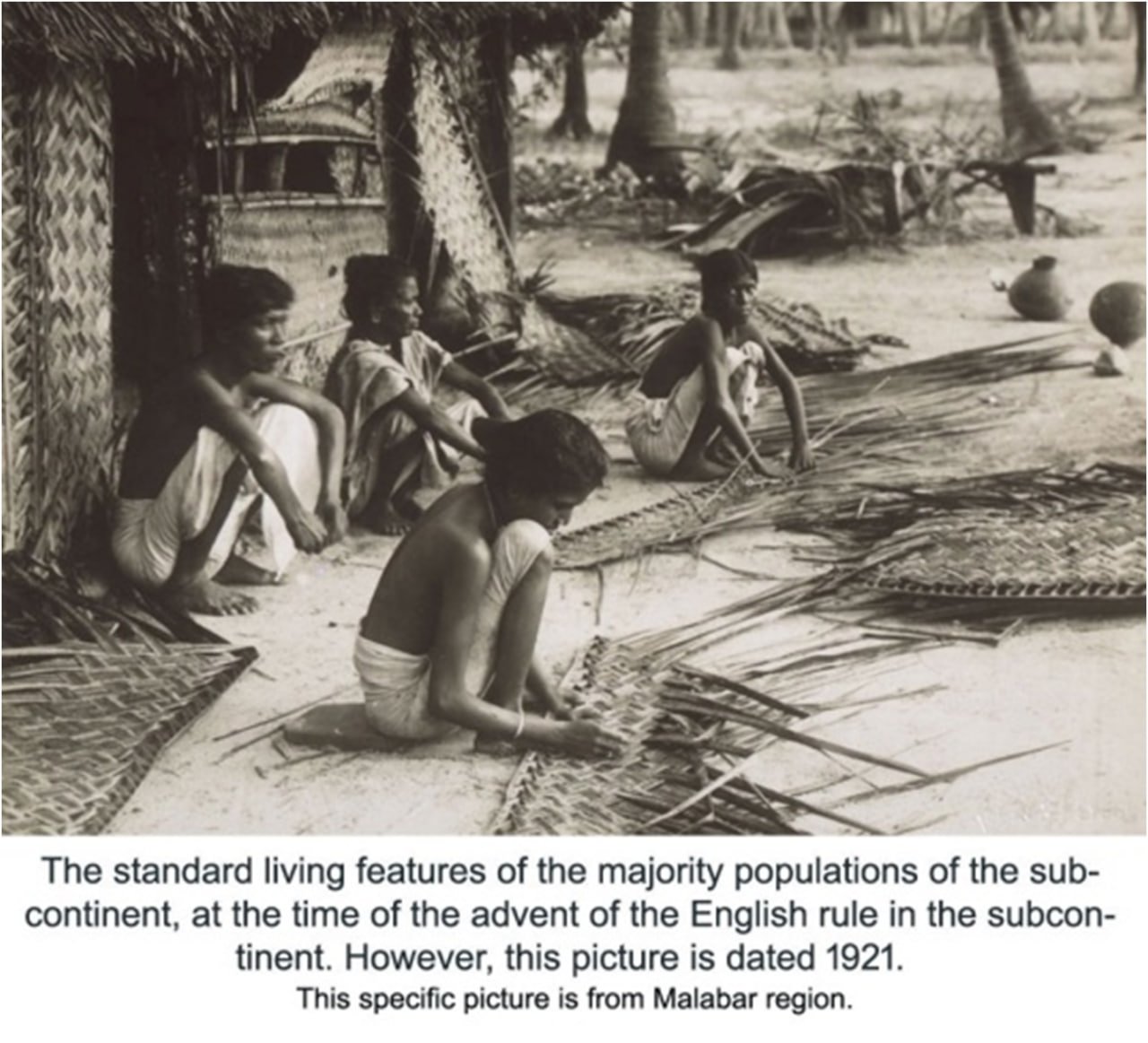

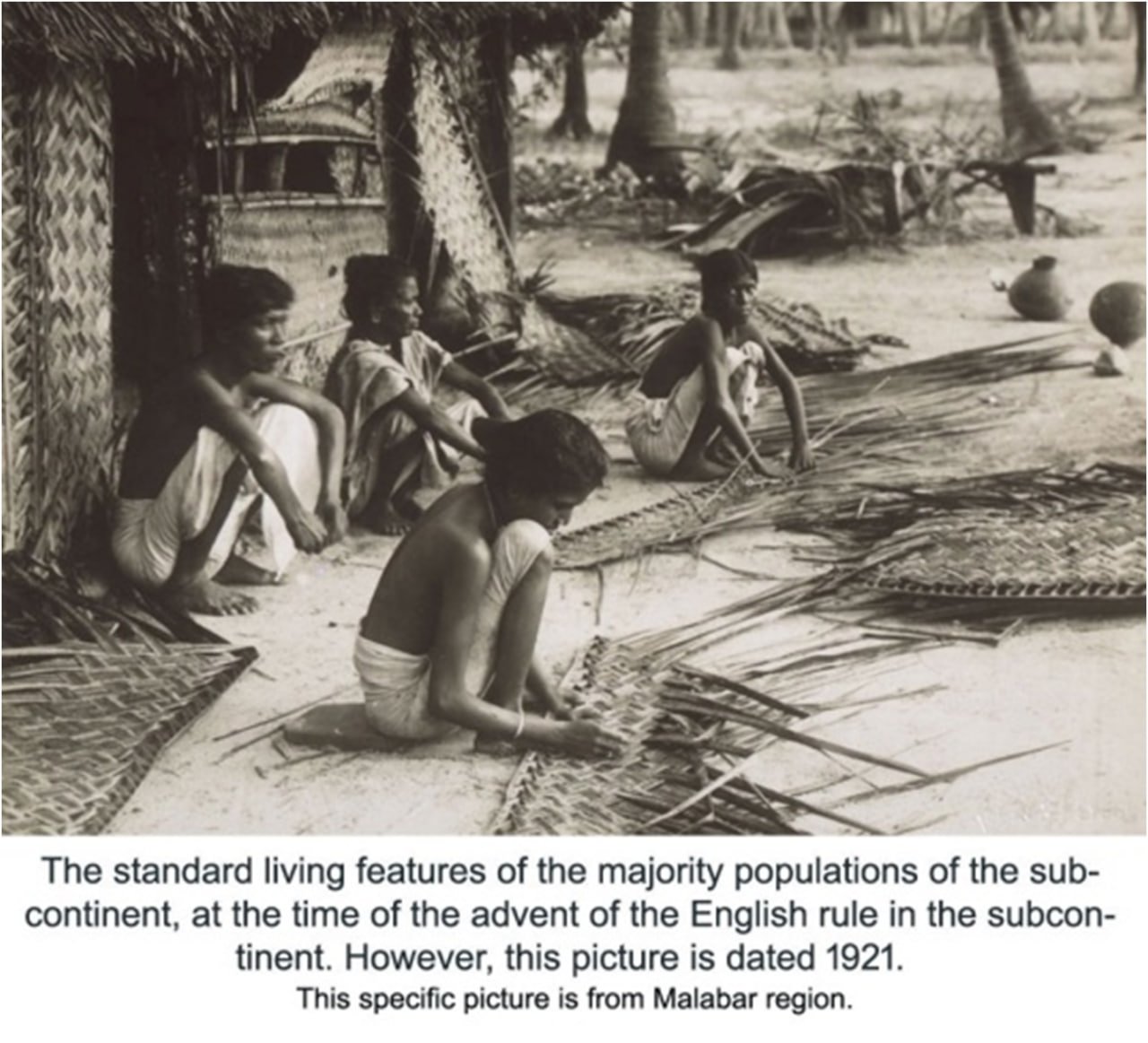

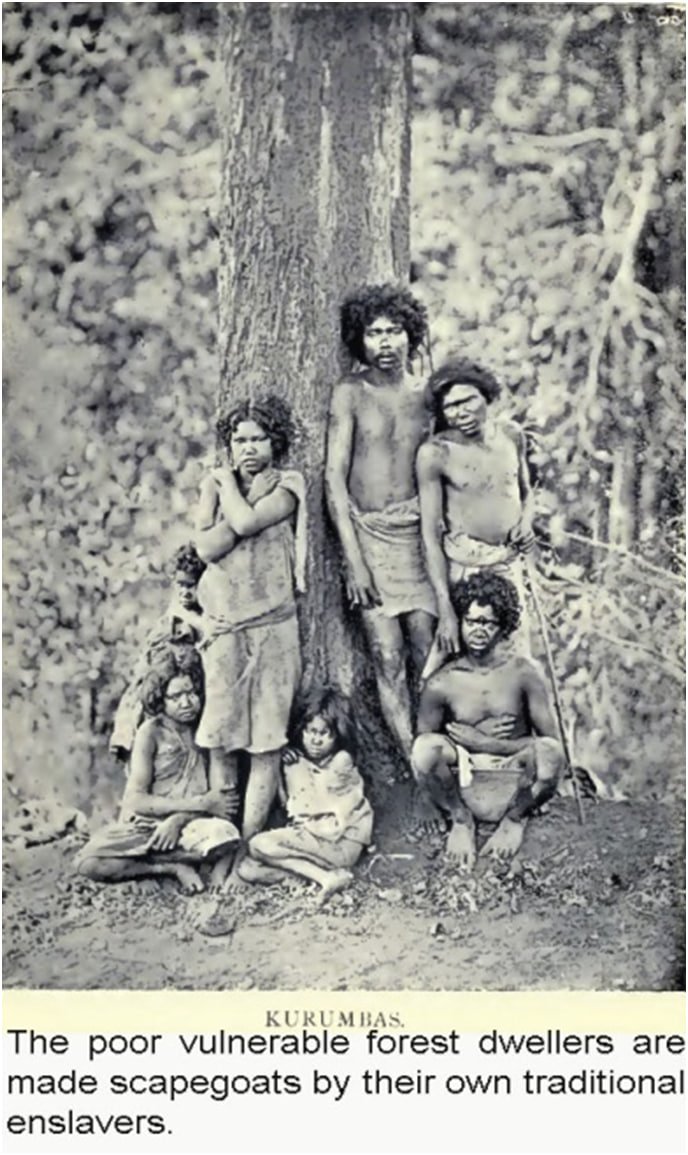

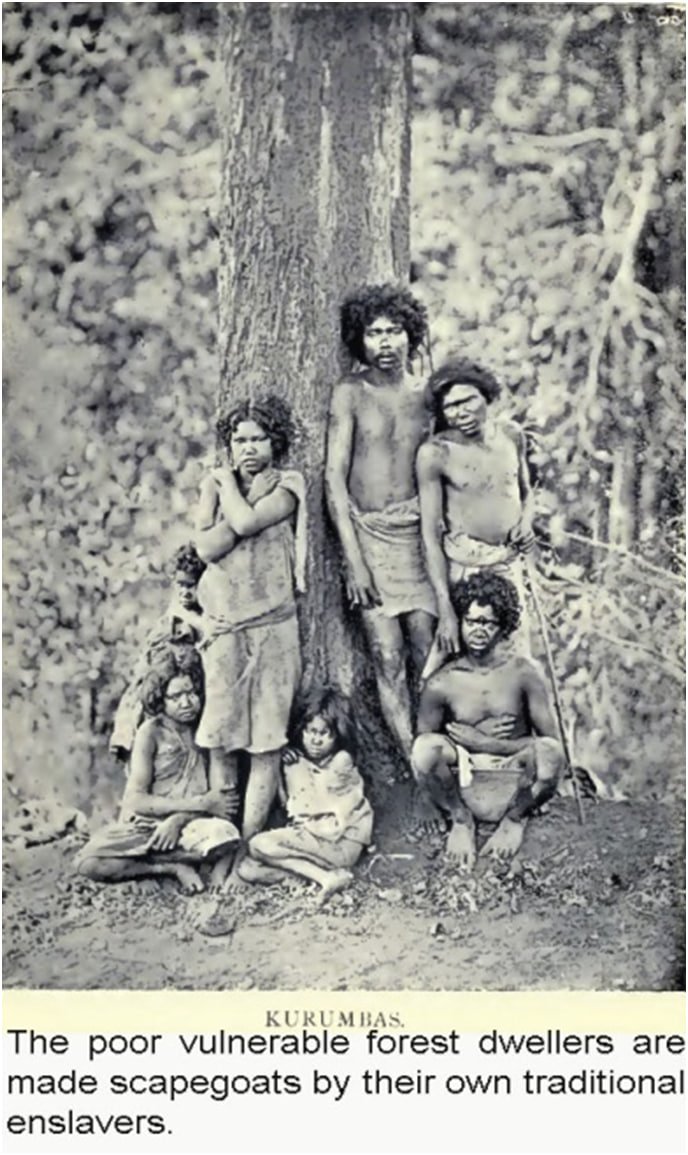

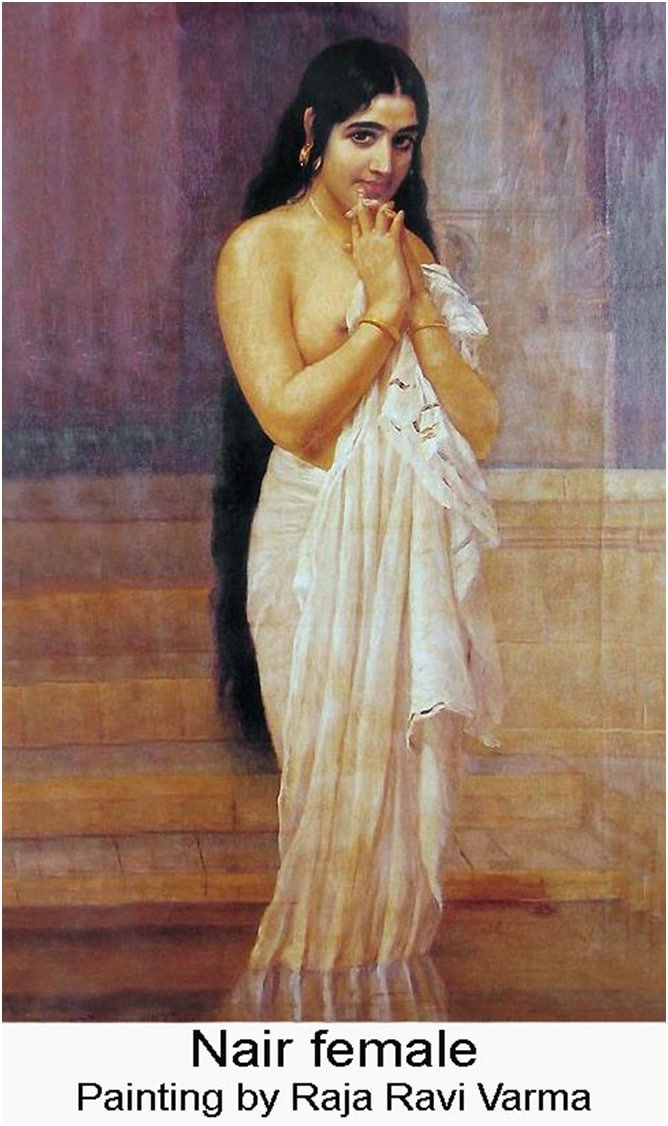

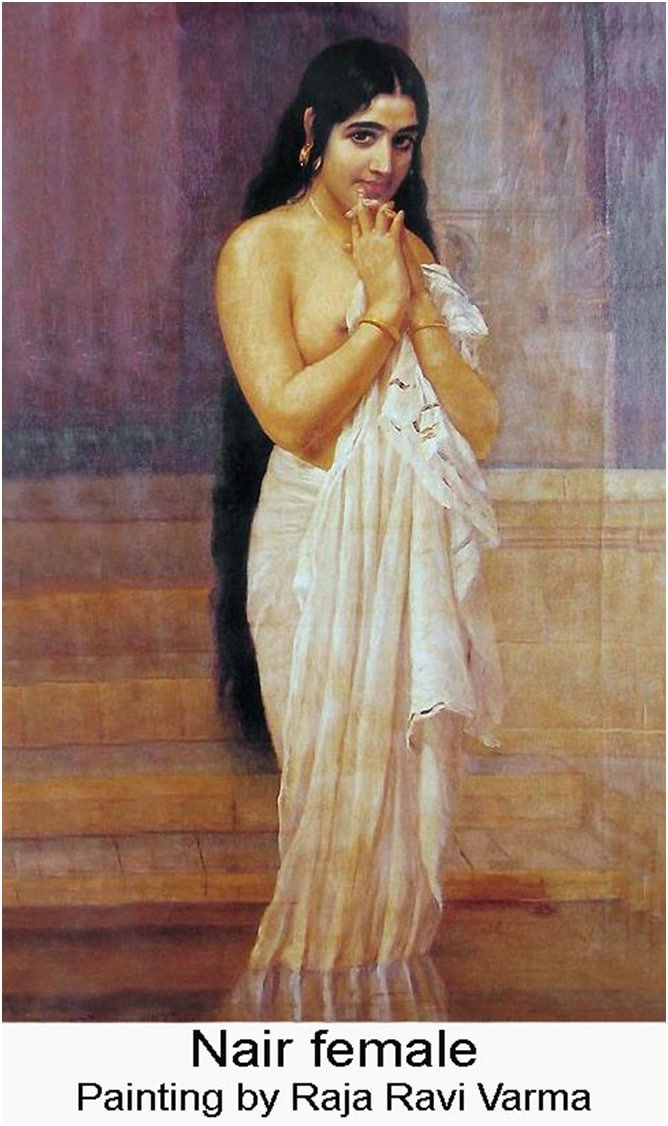

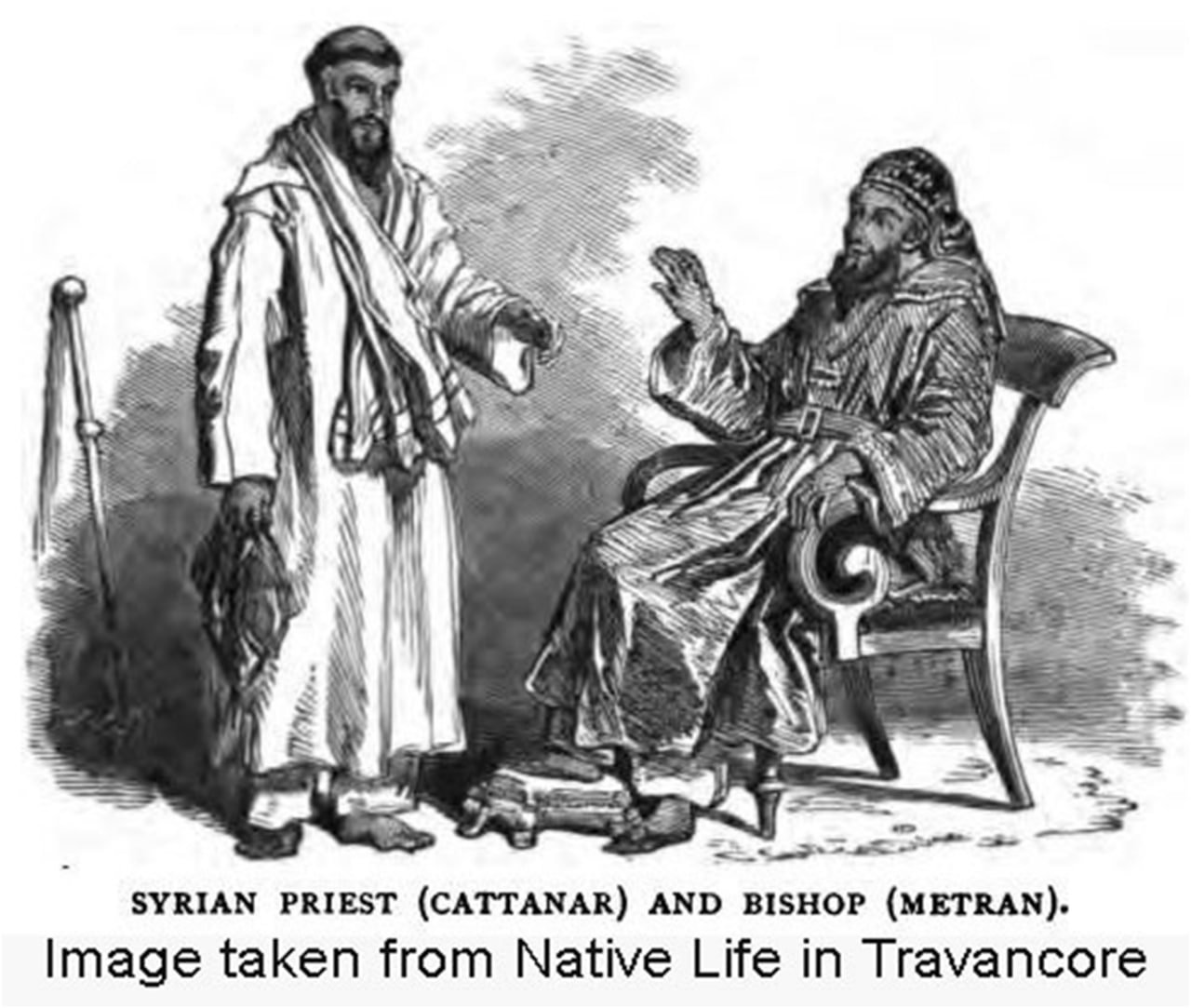

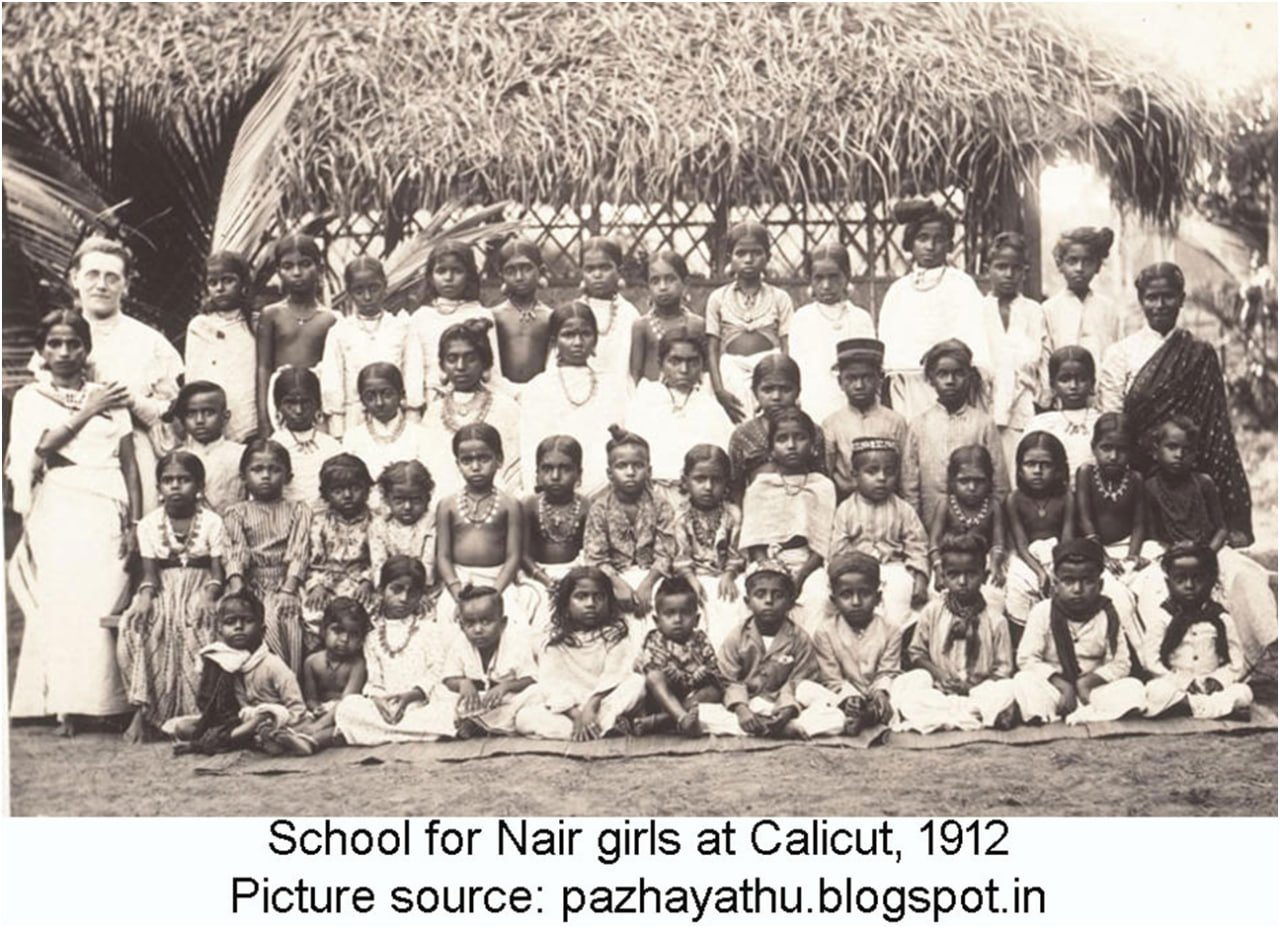

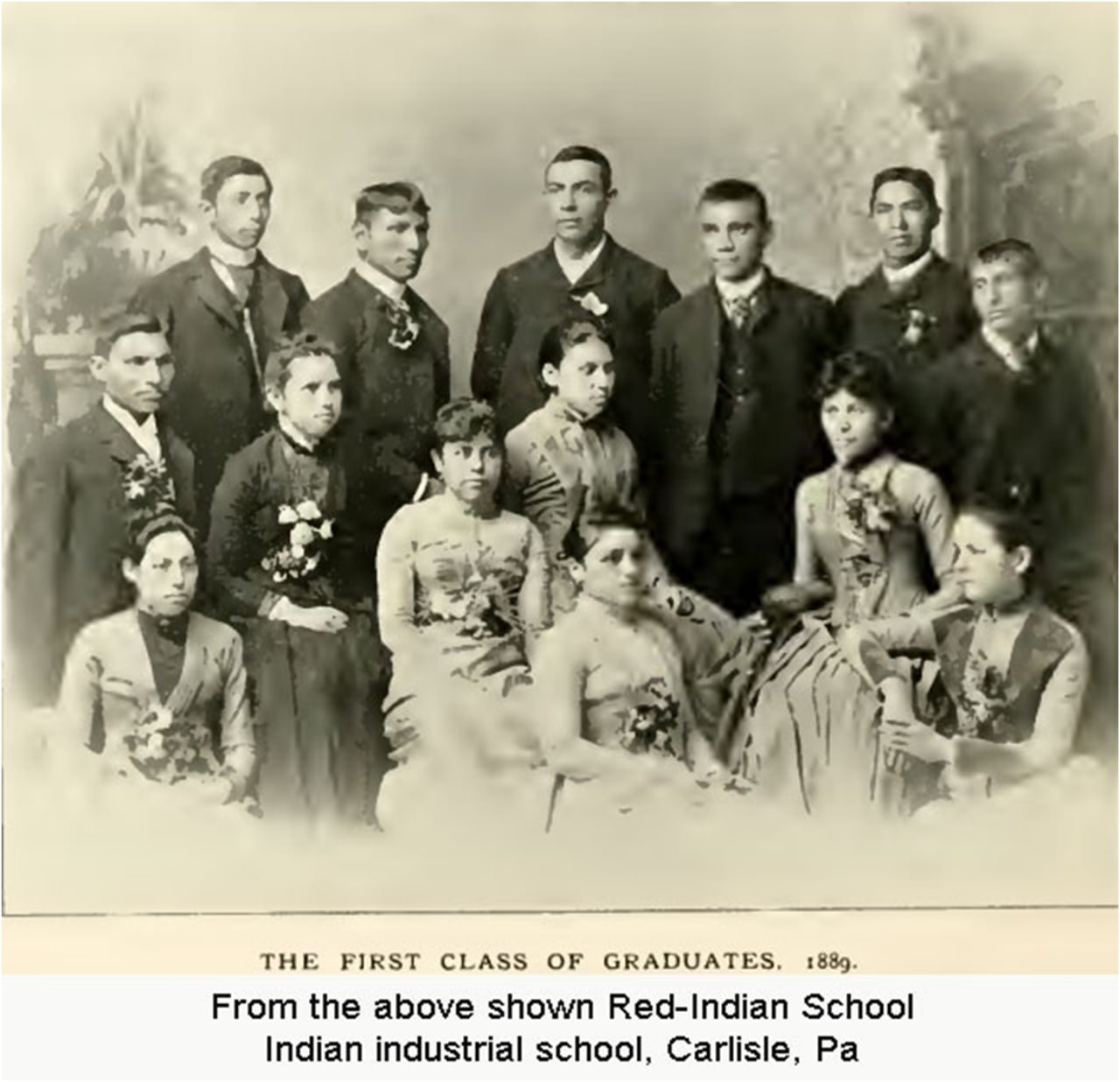

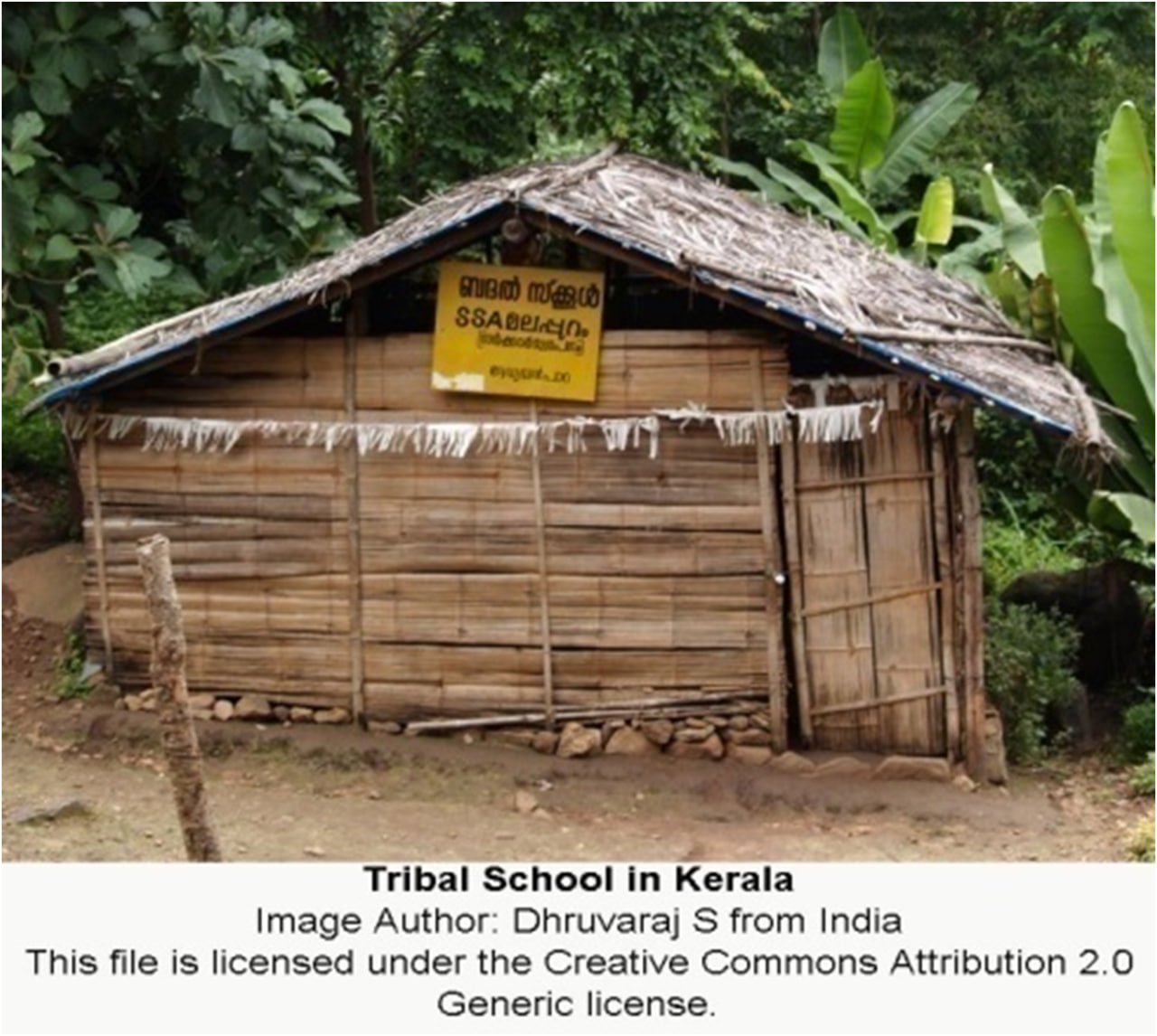

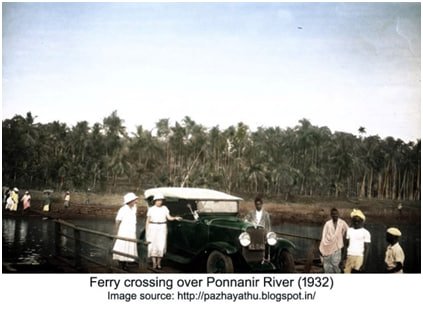

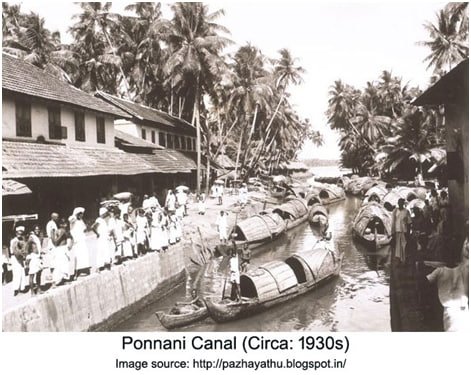

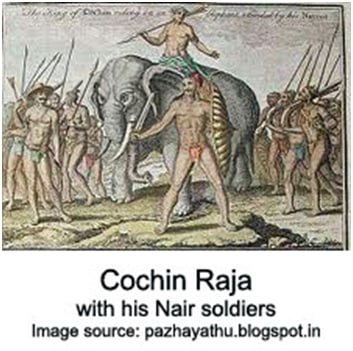

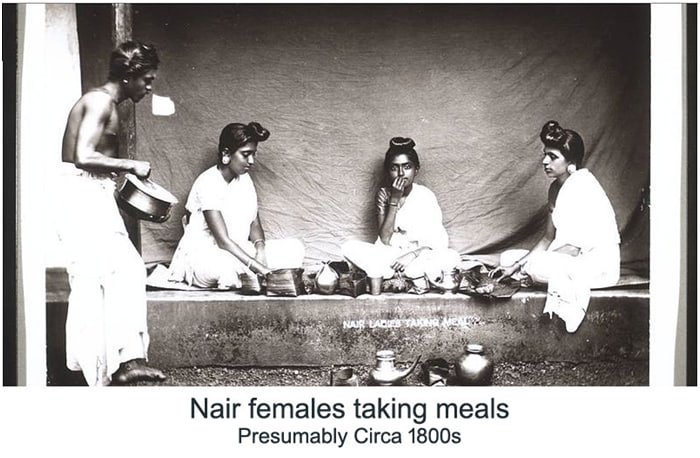

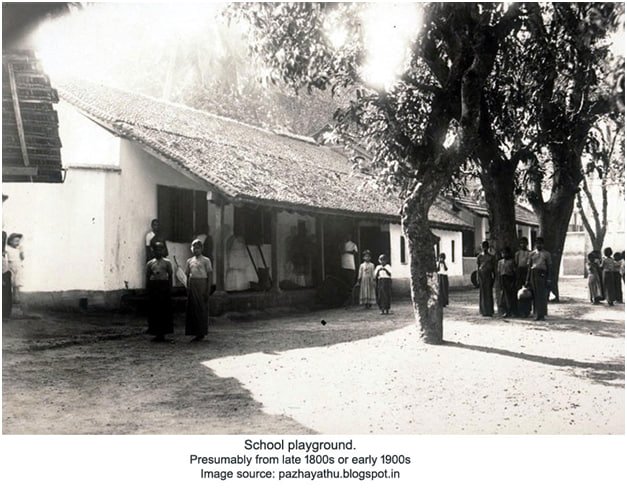

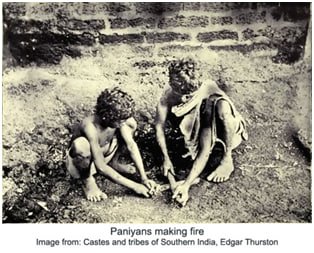

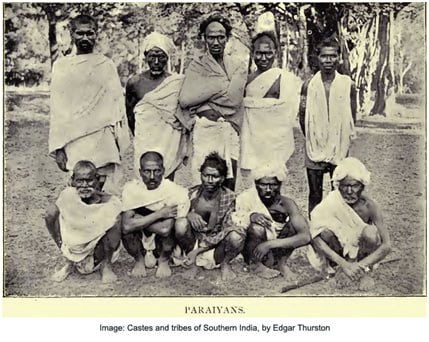

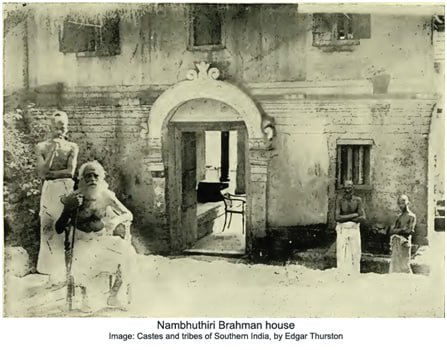

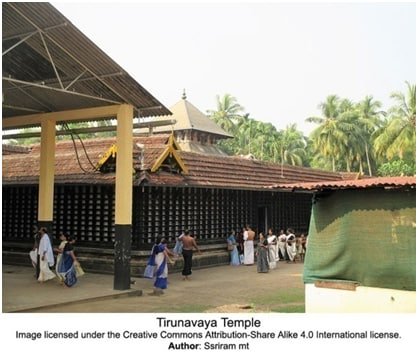

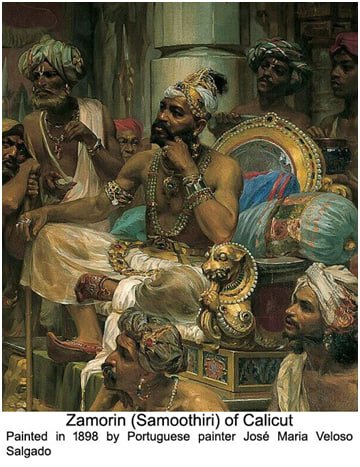

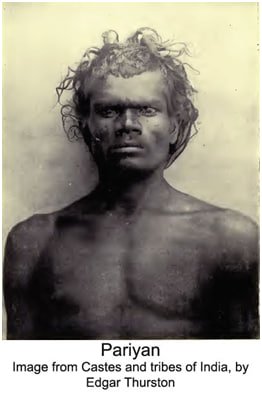

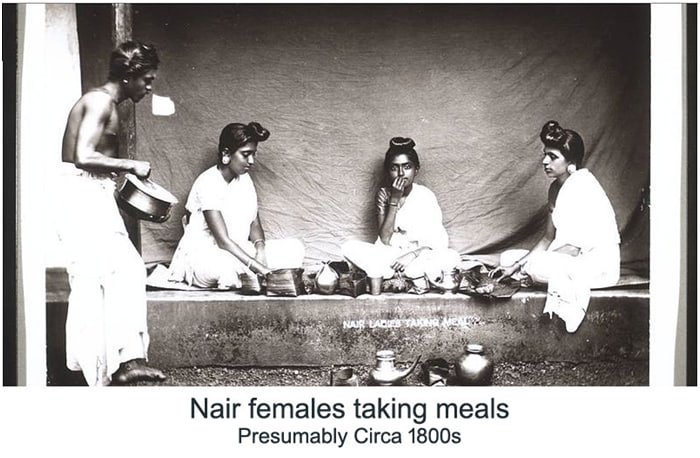

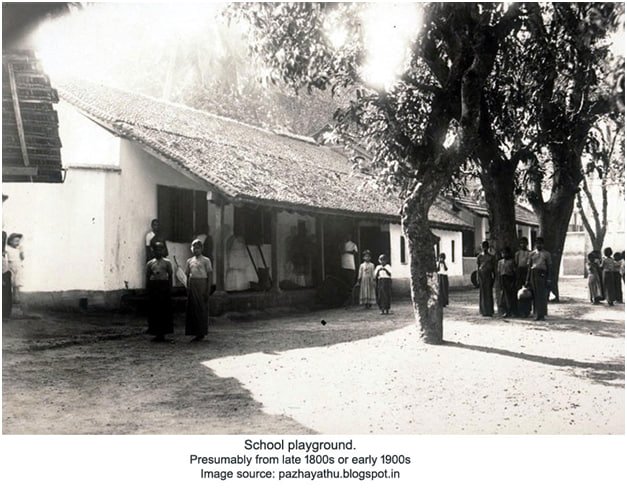

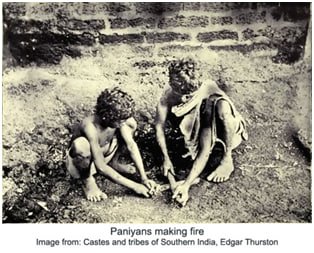

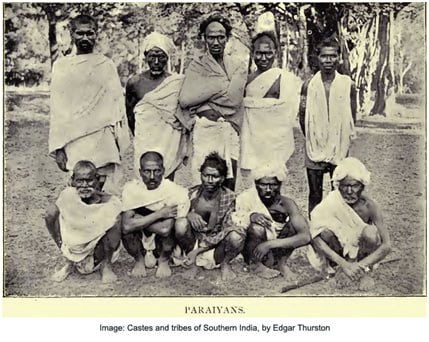

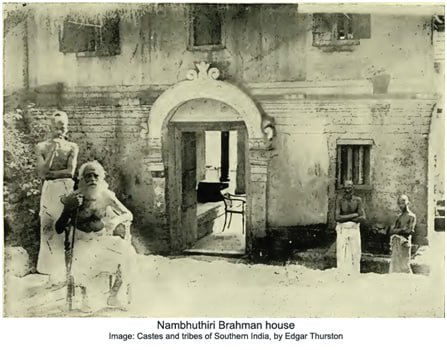

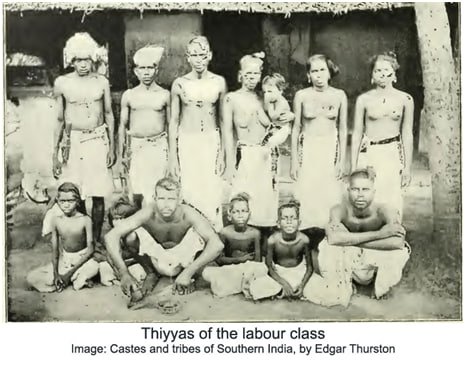

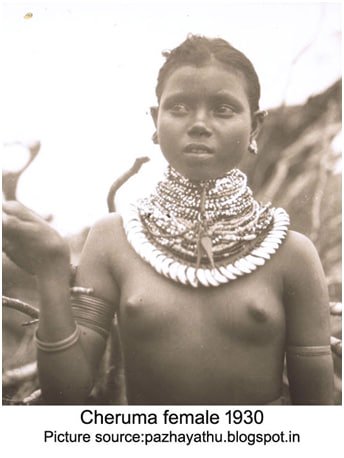

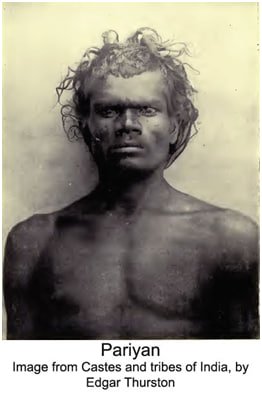

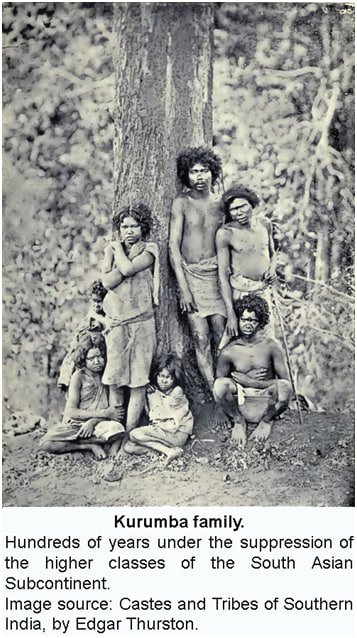

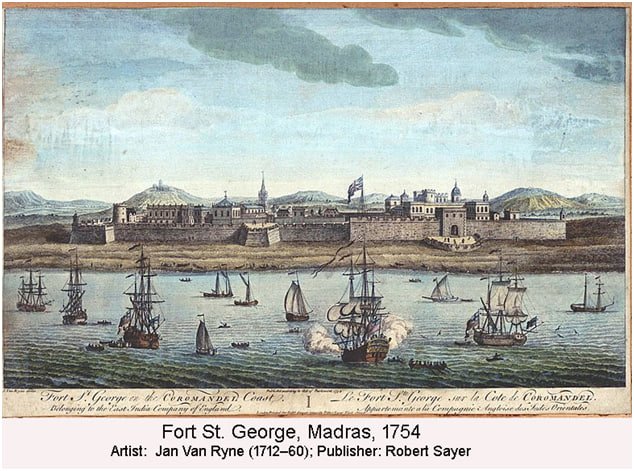

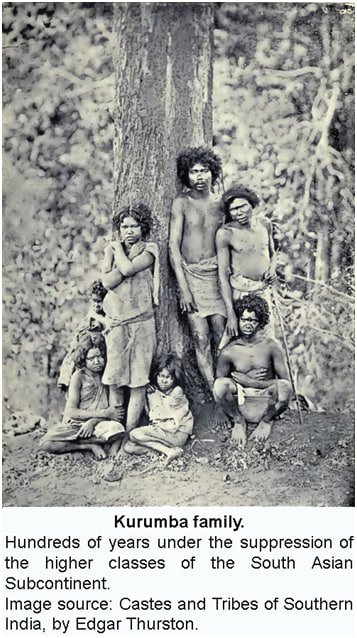

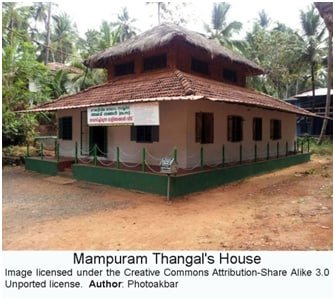

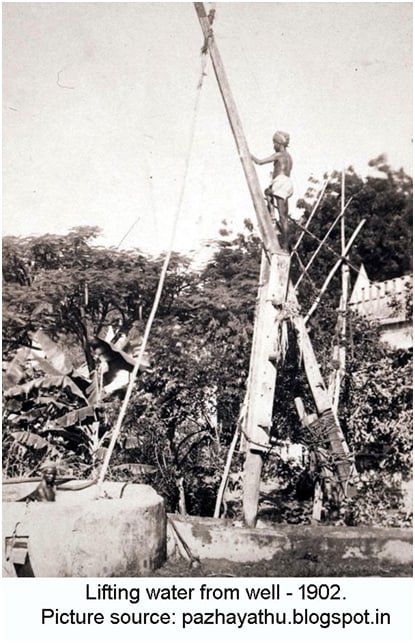

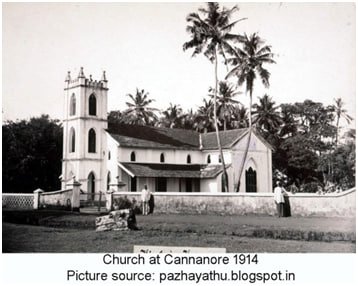

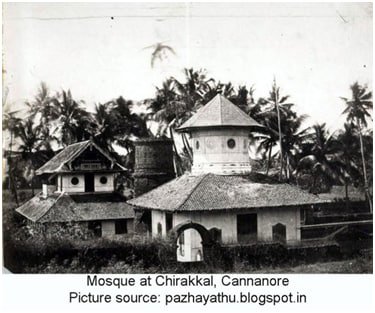

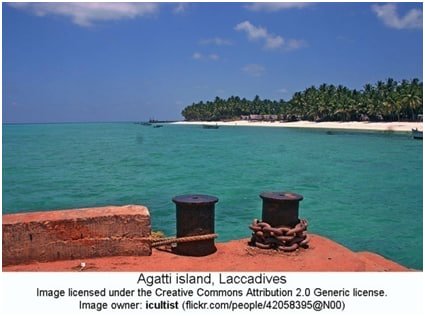

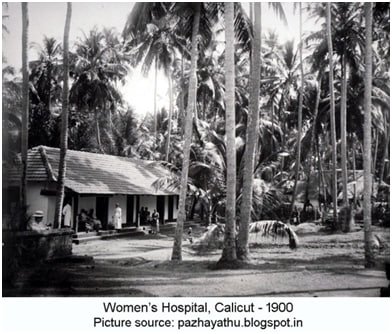

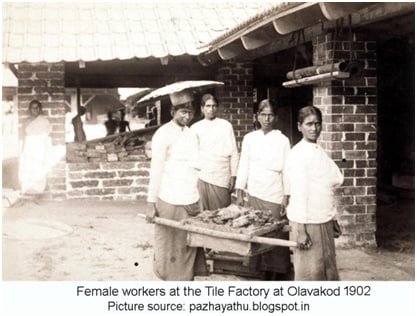

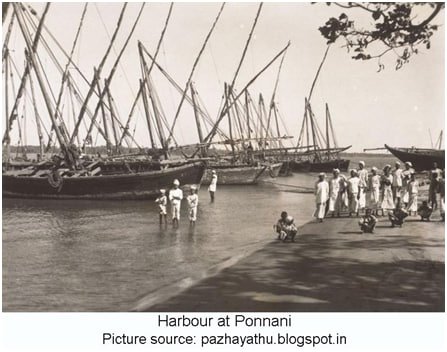

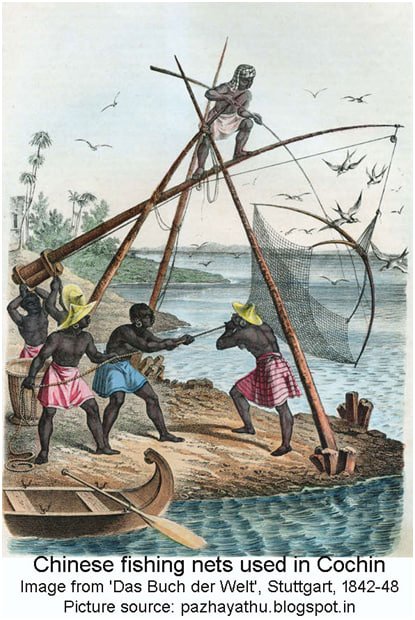

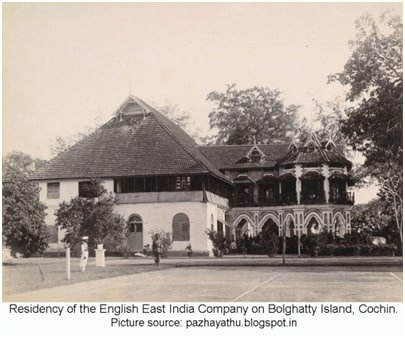

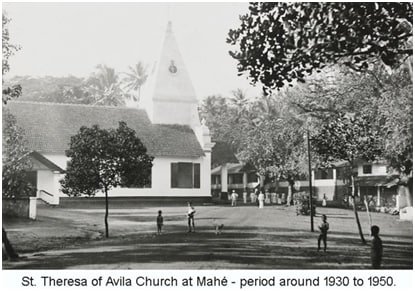

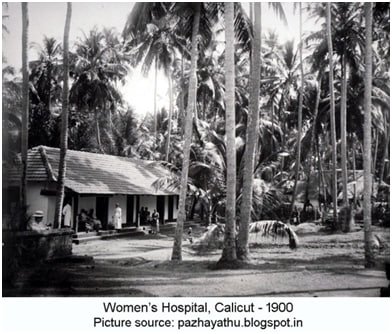

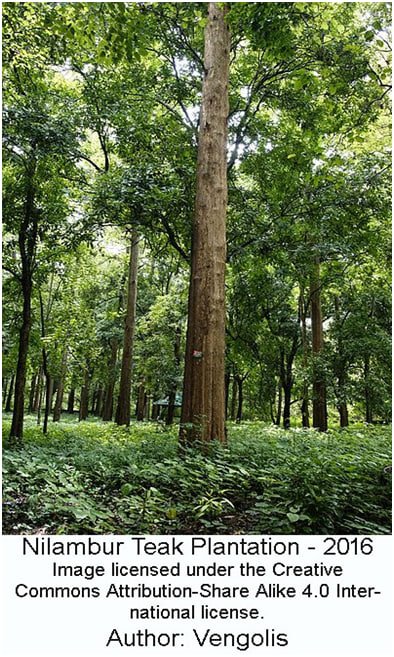

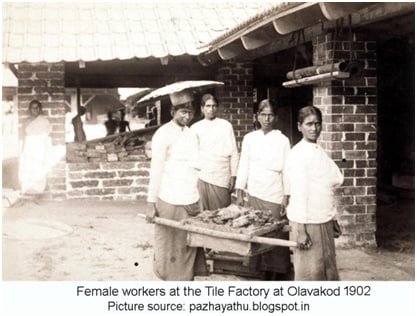

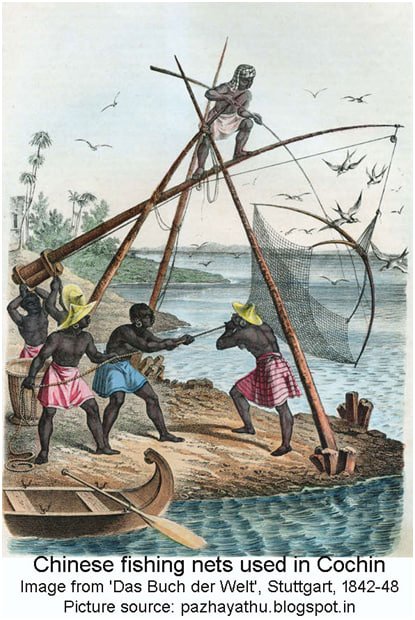

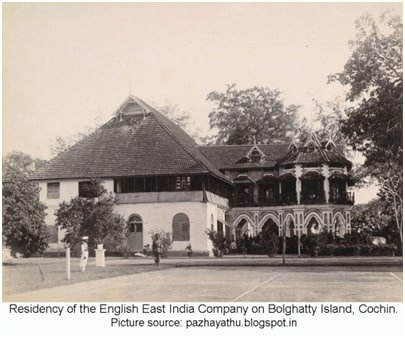

At the end of each chapter, if there is space, a picture depicting the real looks of the ordinary peoples of this subcontinent is placed. Most of them do not represent the social leaders of the place of those times. Just the oppressed peoples of the land.

However, in this commentary of mine, I have tried to insert a lot of such bits and pieces of information, by directly quoting the lines from ‘Malabar’. On these quoted lines, I have built up a lot of arguments, and also added a lot of explanations and interpretations. I do think that it is much easy to go through my Commentary than to read the whole of William Logan's book 'Malabar'. However, the book, Malabar, contains much more items, than what this Commentary can aspire to contain.

This book, Malabar, will give very detailed information on how a small group of native-Englishmen built up a great nation, by joining up extremely minute bits of barbarian and semi-barbarian geopolitical areas in the South Asian Subcontinent.

This Commentary of mine is of more than 240,000 words. I have changed the erroneous US-English spelling seen in the text, into Englander-English (English-UK). It seemed quite incongruous that an English book should have such an erroneous spelling. Maybe it is part of the doctoring done around 1950.

At the end of each chapter, if there is space, a picture depicting the real looks of the ordinary peoples of this subcontinent is placed. Most of them do not represent the social leaders of the place of those times. Just the oppressed peoples of the land.

Last edited by VED on Fri Feb 16, 2024 12:09 pm, edited 5 times in total.

Words

q #

Al-Biruni (Circa: 4 September 973 – 9 December 1048):

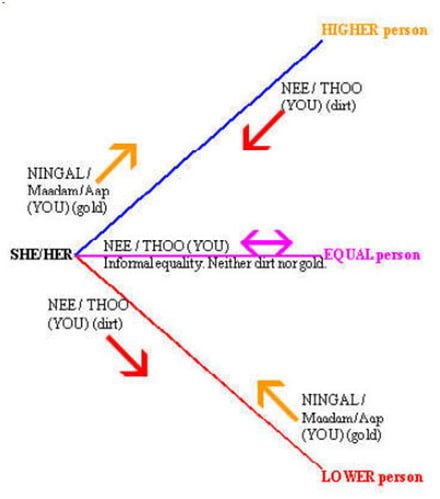

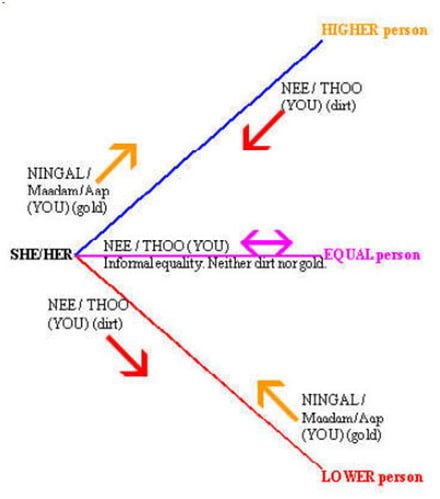

Quote from Malabar by William Logan, on the quality of the historical records of the South Asian Subcontinent:

Matthew 7:6 Bible - King James Version:

Al-Biruni (Circa: 4 September 973 – 9 December 1048):

We can only say, stupidity is an illness for which there is no cure. They (the peoples of south-Asia) believe that there is no country as great as theirs, no nation like theirs, no kings like theirs, no religion like theirs, no science like theirs.

They are arrogant, foolish and vain, self-conceited, and indifferent. They are by nature miserly in sharing their knowledge, and they take the greatest of efforts to hide it from men of another caste among their own people, and also, of course, from foreigners.

According to their firm belief, there is no other country on earth but theirs, no other race of man but theirs, and no human being besides them have any knowledge or science and such other things.

Their conceit is such that, if you inform them of any science or scholar in Khurasan and Persia, they will define you as an idiot and a liar. If they travel and mix with other people in other nations, they would change their mind fast. ....

Quote from Malabar by William Logan, on the quality of the historical records of the South Asian Subcontinent:

... and even in genuinely ancient deeds it is frequently found that the facts to be gathered from them are unreliable owing to the deeds themselves having been forged at periods long subsequent to the facts which they pretend to state.

Matthew 7:6 Bible - King James Version:

Give not that which is holy unto the dogs, neither cast ye your pearls before swine, lest they trample them under their feet, and turn again and rend you.

Last edited by VED on Fri Feb 16, 2024 12:08 pm, edited 5 times in total.

CONTENTS

contents #

CLICK HERE

Go to Malabar Manual

Please note that on a computer browser, ALT & Back arrow, will be move the page to previous view / location. On mobile devices, touching the Back arrow found on the bottom of the screen will move the page to the previous view / locatioon.

COMMENTARY CONTENTS

Cover page

Book profile

Ancient quotes relevent to South Asia

1. My aim

2. The information divide

3. The layout of the book

4. My own insertions

5. The first impressions about the contents

6. India and Indians

7. An acute sense of not understanding

8. Entering a terrible social system

9. The doctoring and the manipulations

10. Missed or unmentioned, or fallacious

11. NONSENSE

12. Nairs / Nayars

13. A digression to Thiyyas

14. Designing the background

15. Content of current-day populations

16. Nairs / Nayars

17. The Thiyya quandary

18. The terror that perched upon the Nayars

19. The entry of the Ezhavas

20. Converted Christian Church exertions

21. Ezhava-side interests

22. The takeover of Malabar

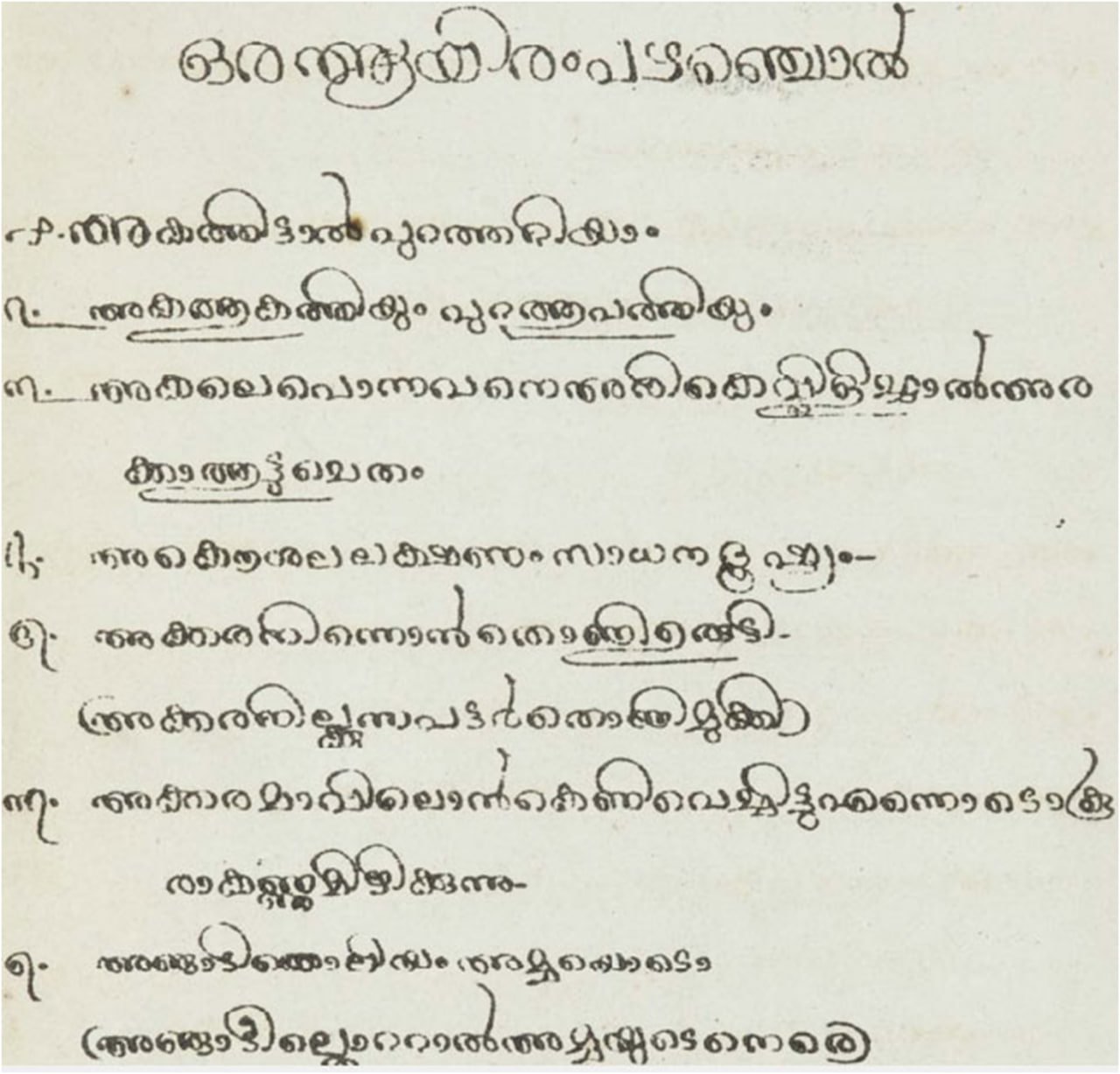

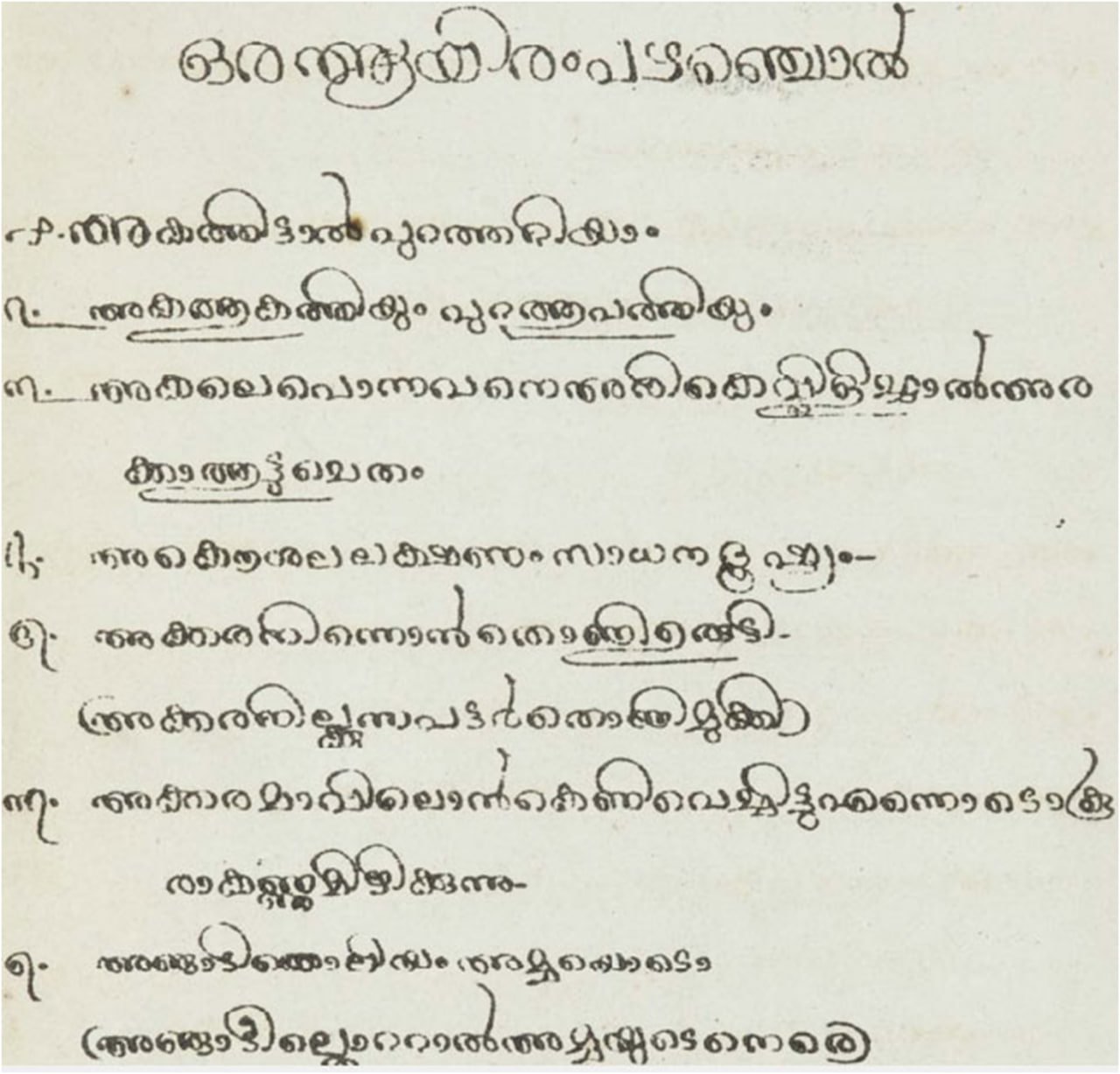

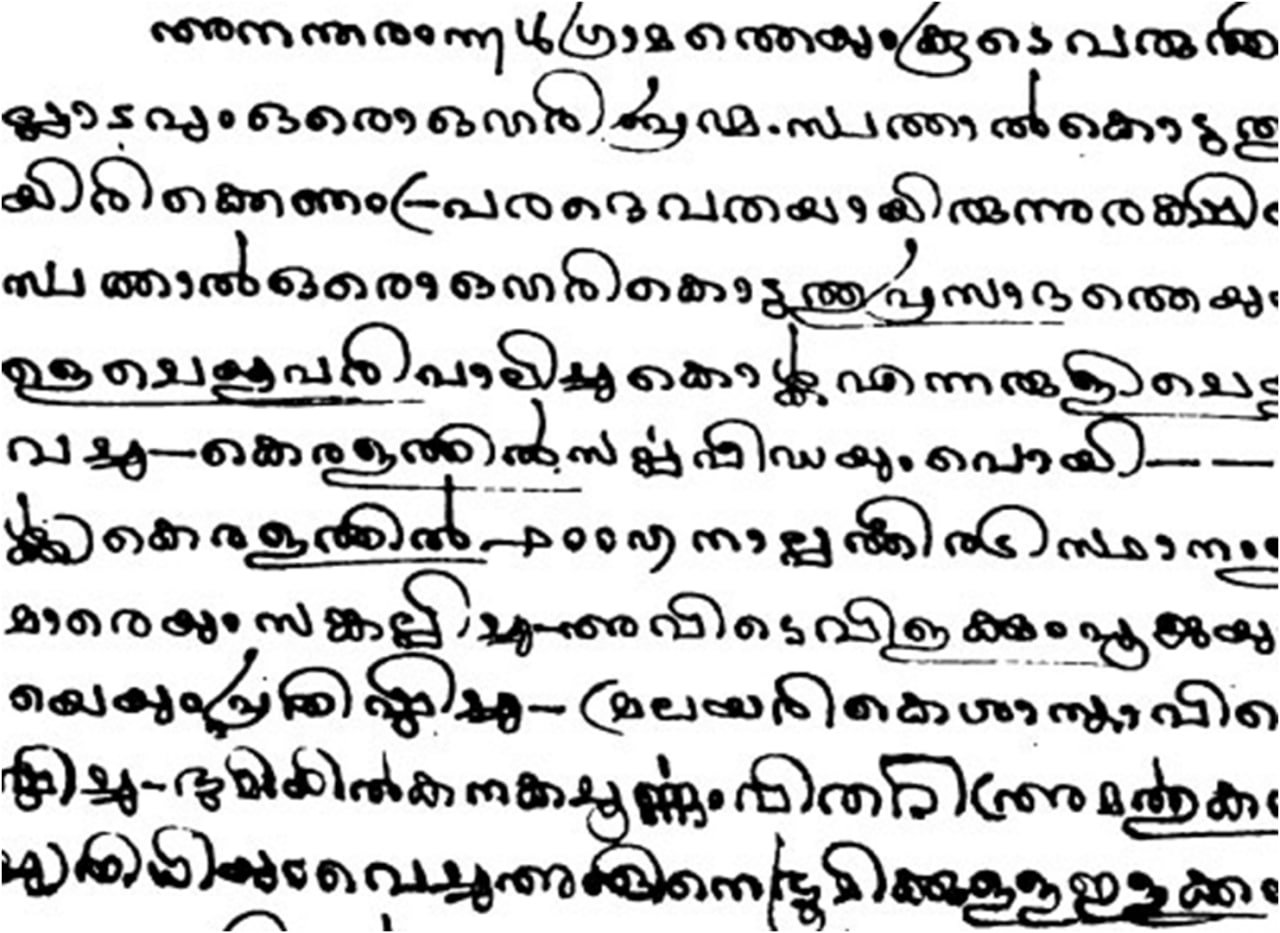

23. Keralolpathi

24. About the language Malayalam

25. Superstitions

26. Misconnecting with English

27. Feudal language

28. Claims to great antiquity

29. Piracy

30. Caste system

31. Slavery

32. The Portuguese

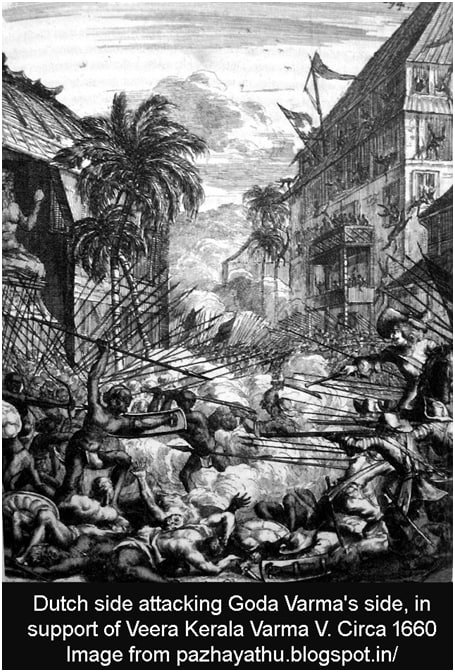

33. The Dutch

34. The French

35. The ENGLISH

36. Kottayam

37. Mappillas

38. Mappilla outrages on Nayars & Hindus

39. Mappilla outrage list

40. What is repulsive about the Muslims?

41. Hyder Ali

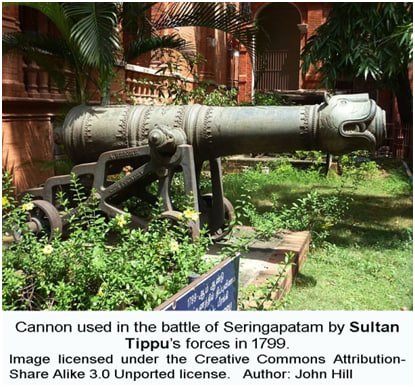

42. Sultan Tippu

43. Women

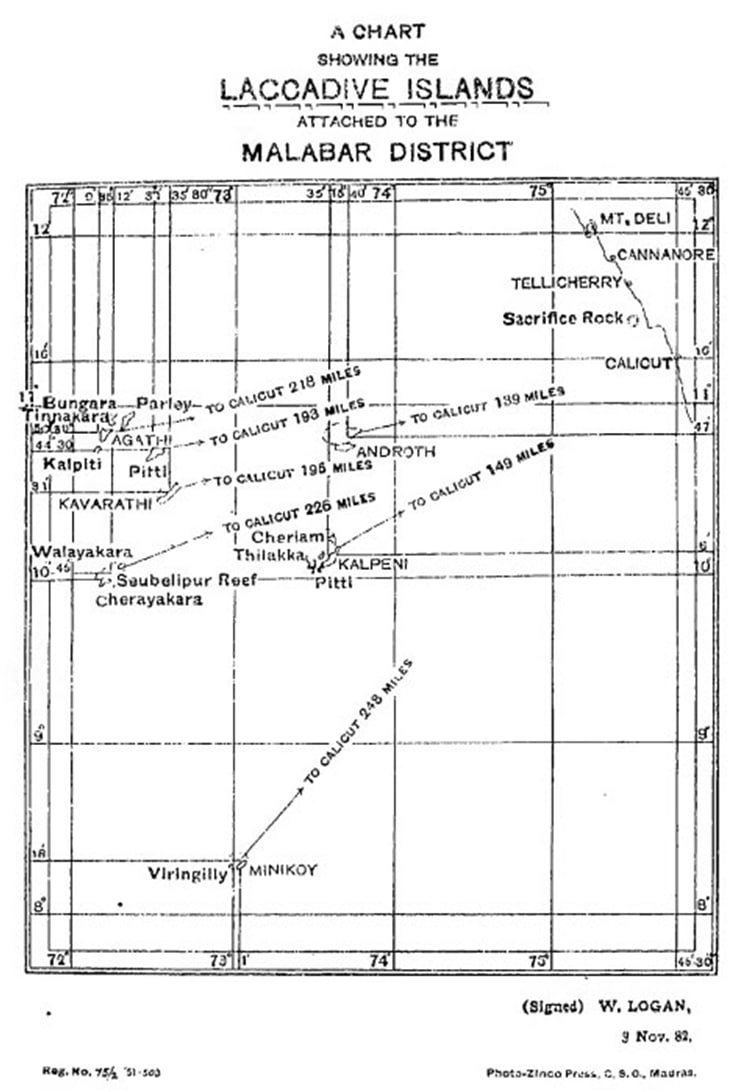

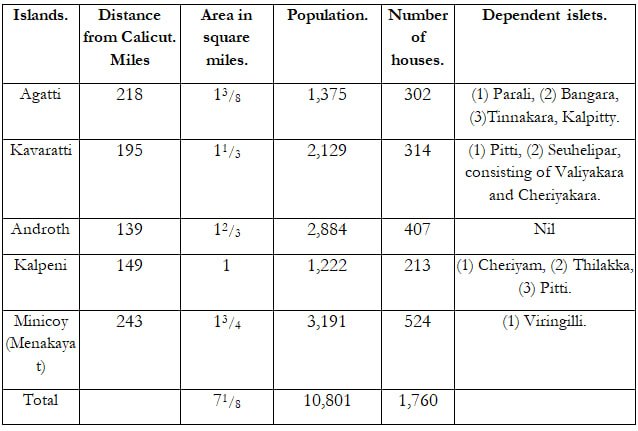

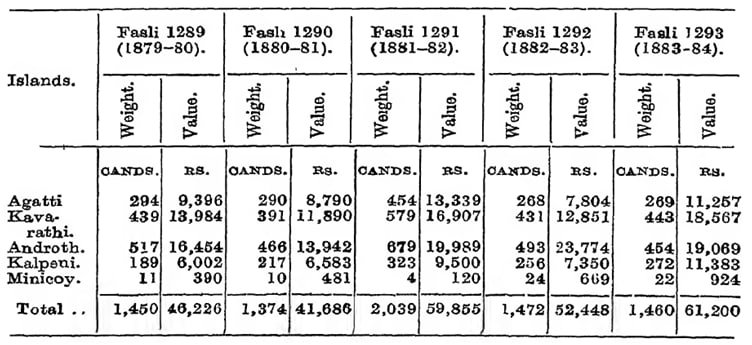

44. Laccadive Islands

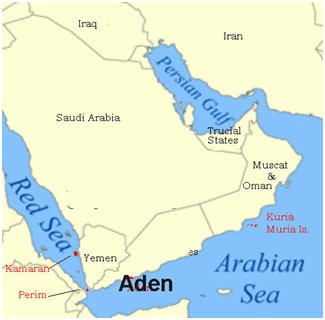

45. Ali Raja

46. Kolathiri

47. Kadathanad

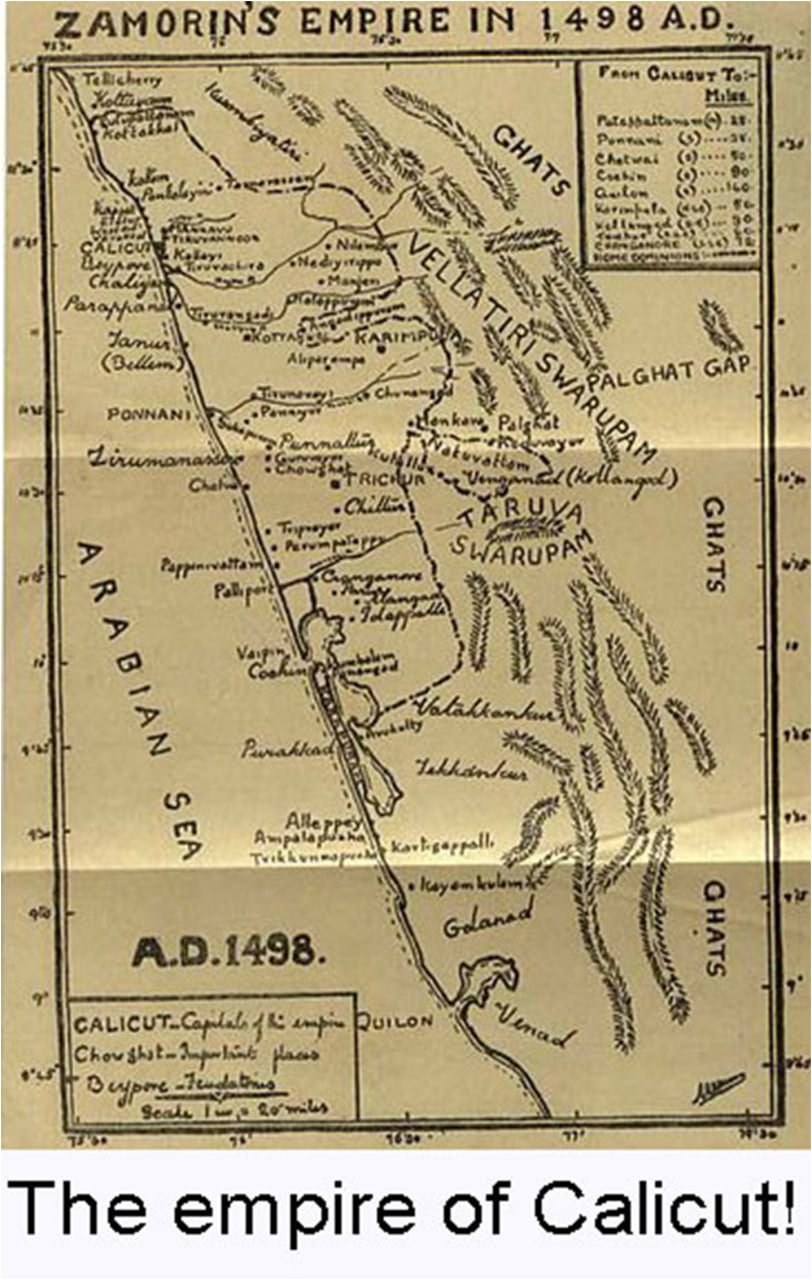

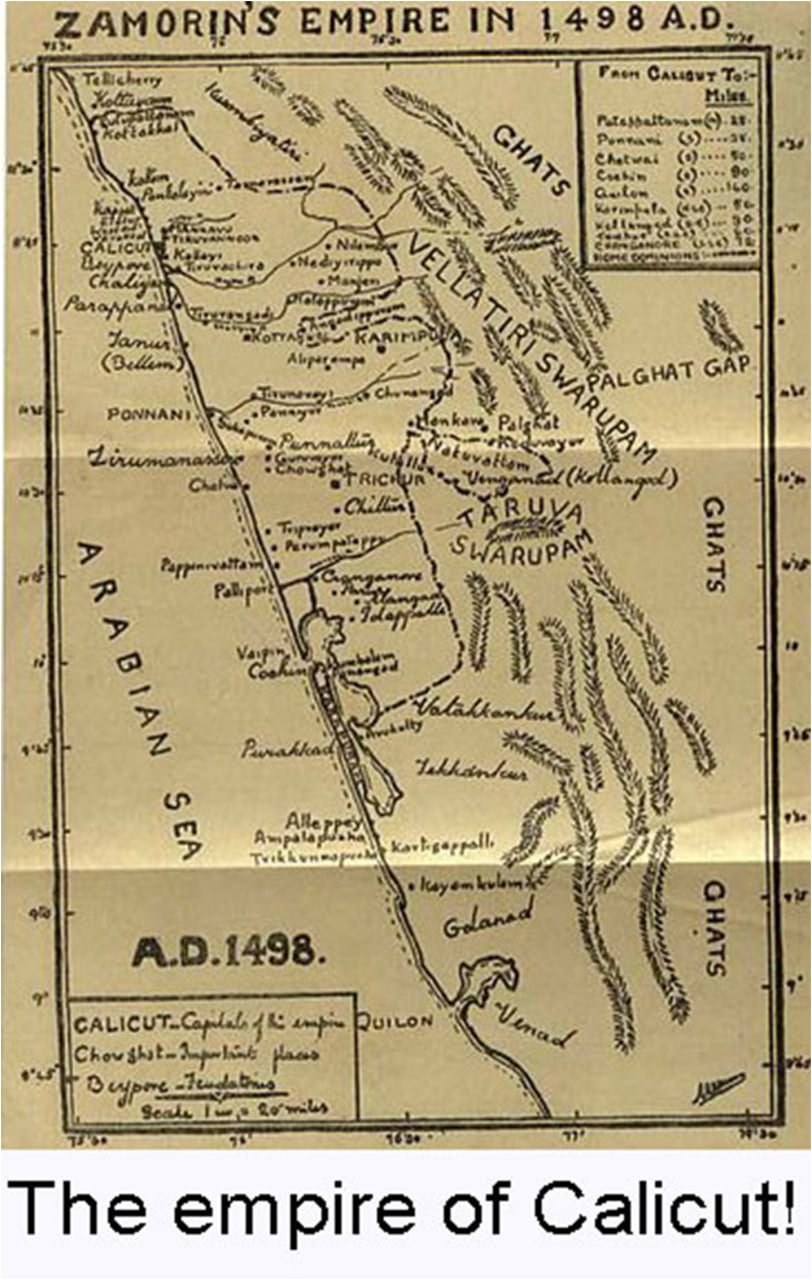

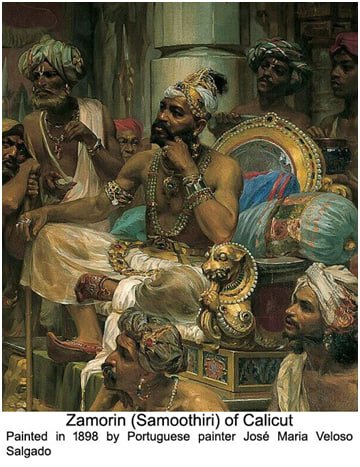

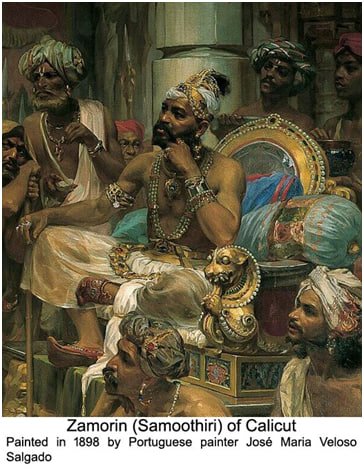

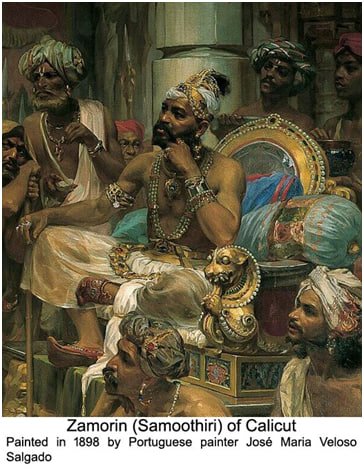

48. The Zamorin and other apparitions

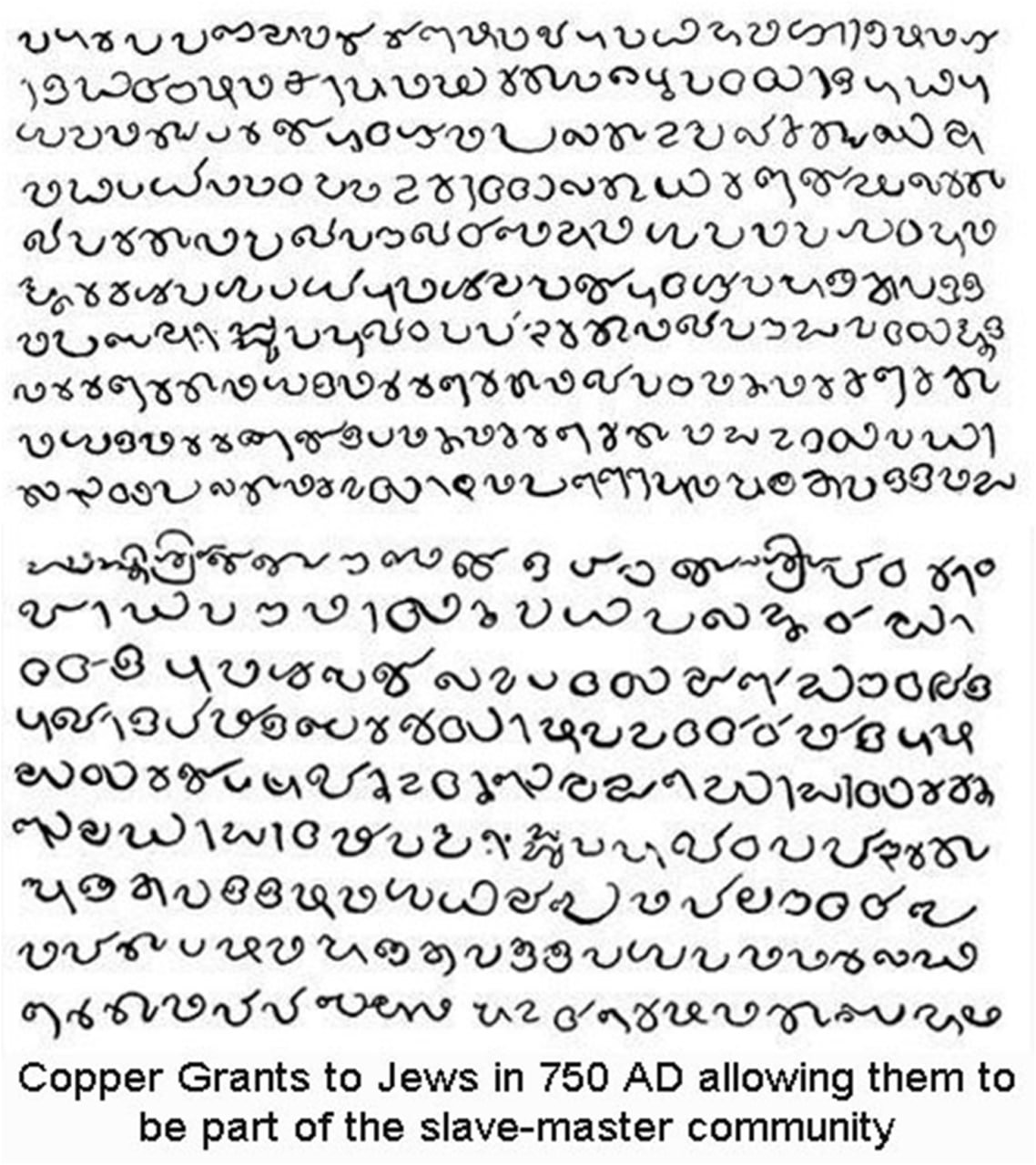

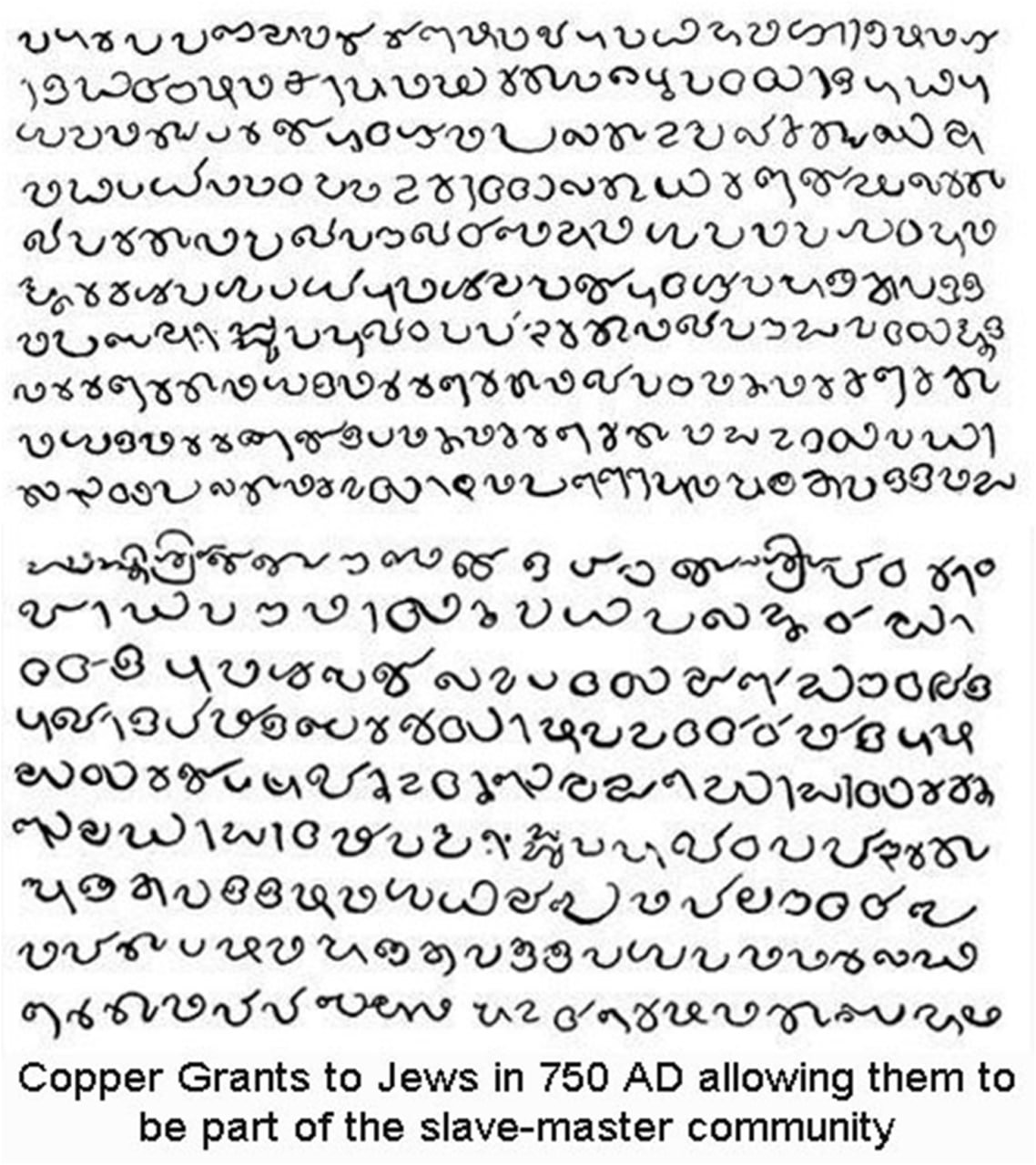

49. The Jews

50. Social customs

51. Hinduism

52. Christianity

53. Pestilence, famine etc.

54. British Malabar vs. Travancore kingdom

55. Judicial

56. Revenue and administrative changes

57. Rajas

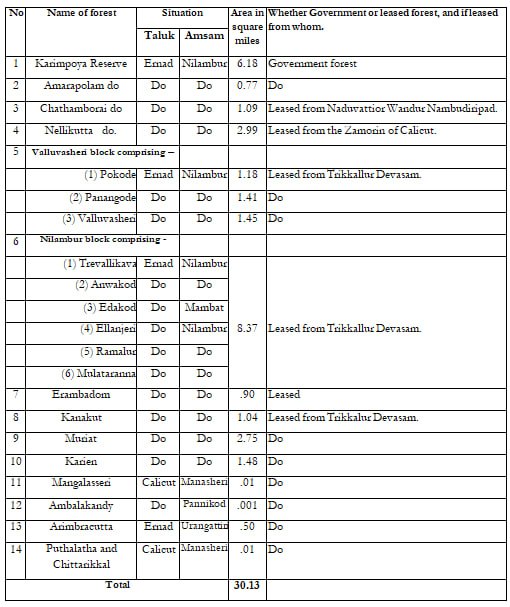

58. Forests

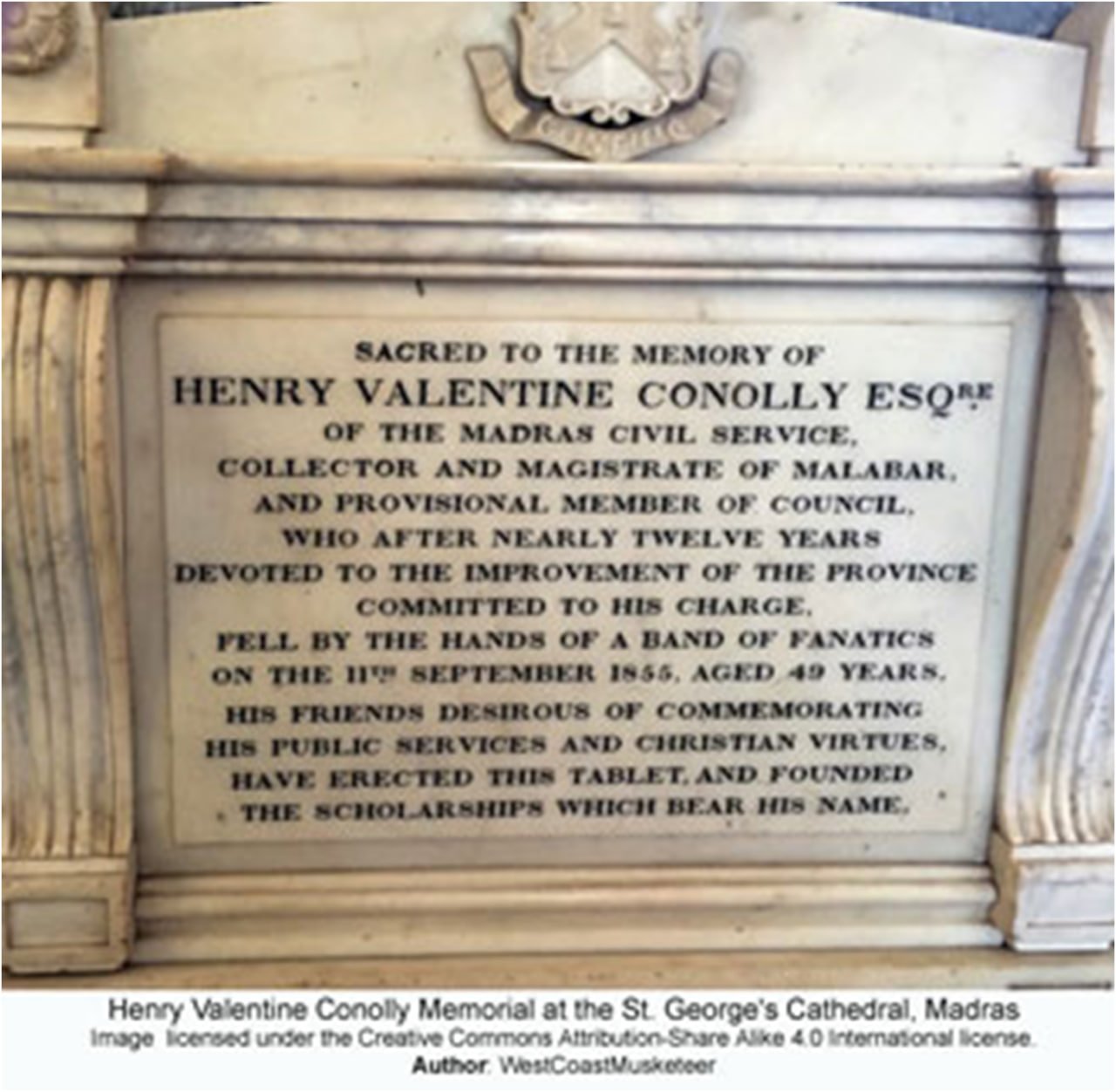

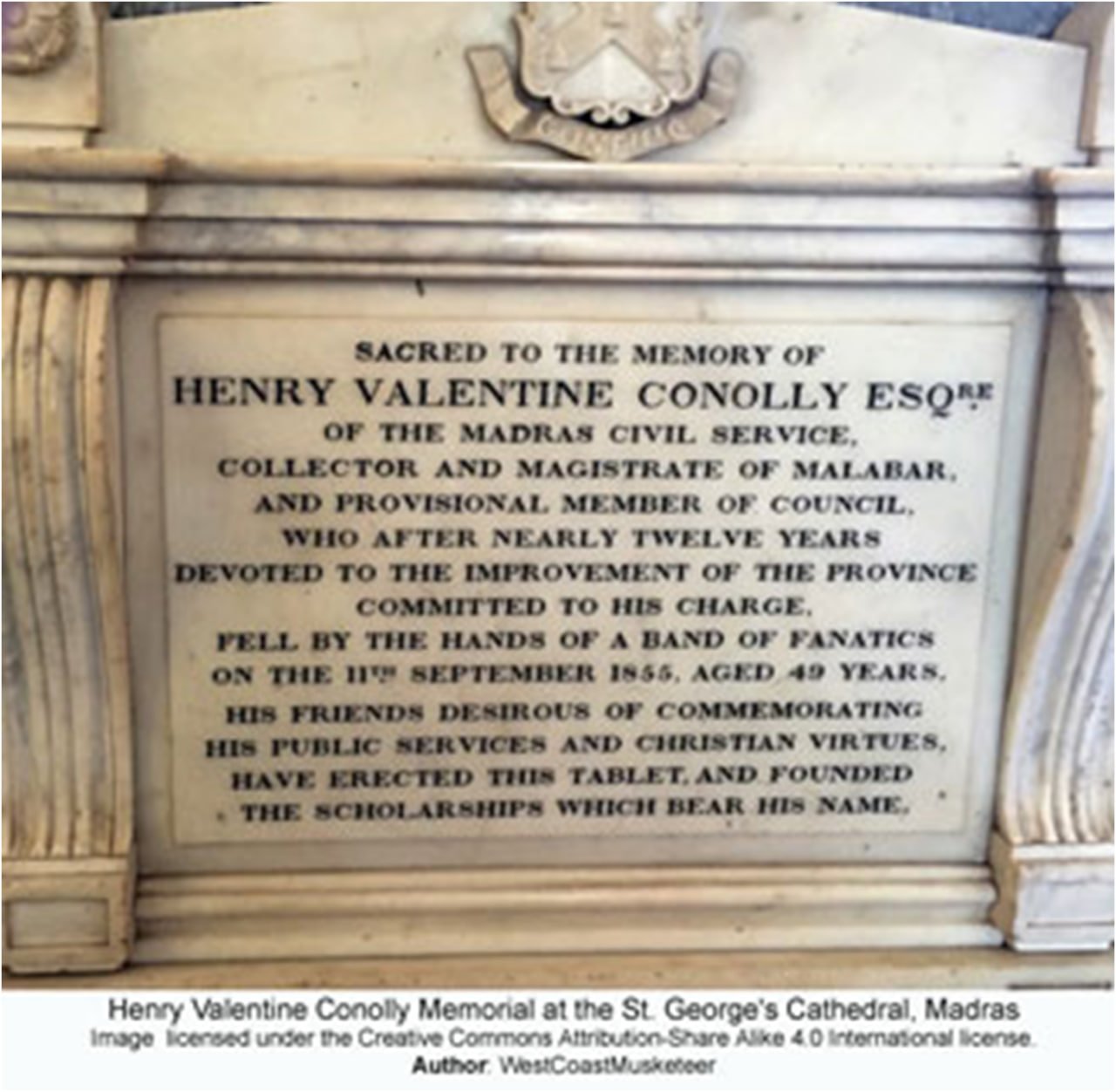

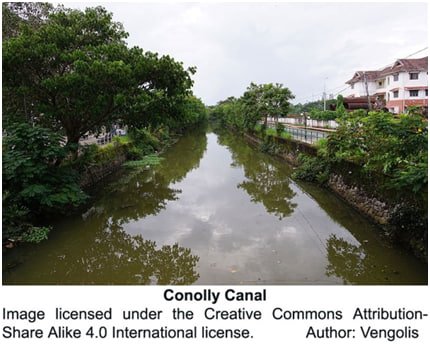

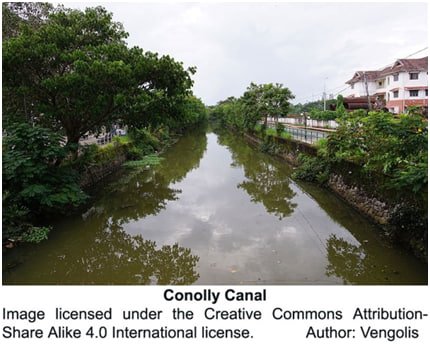

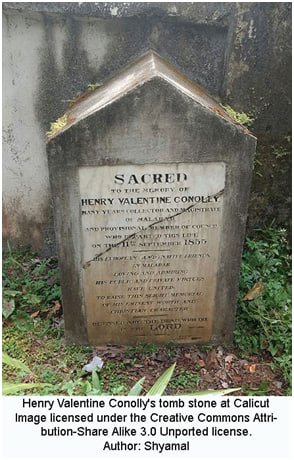

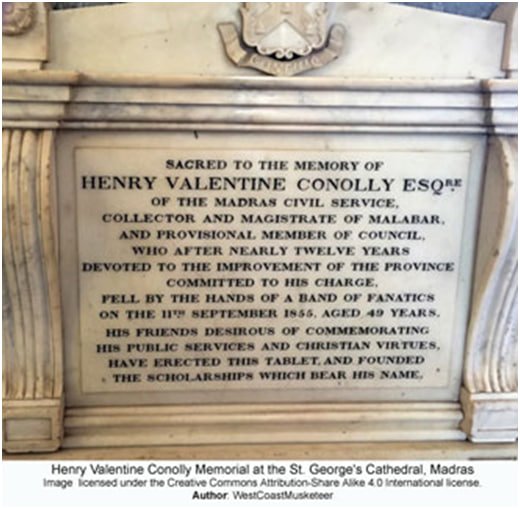

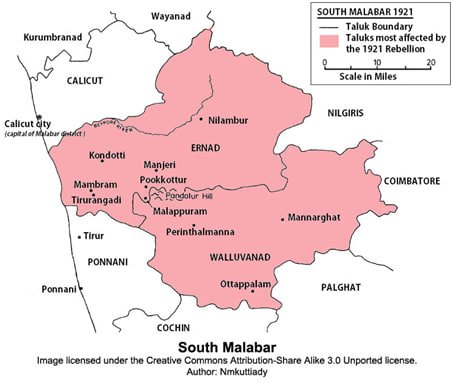

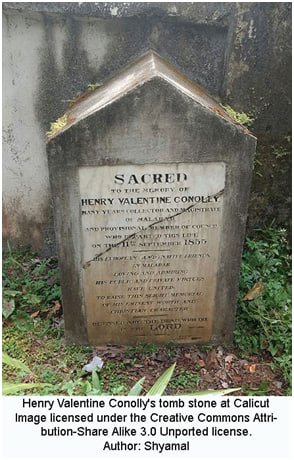

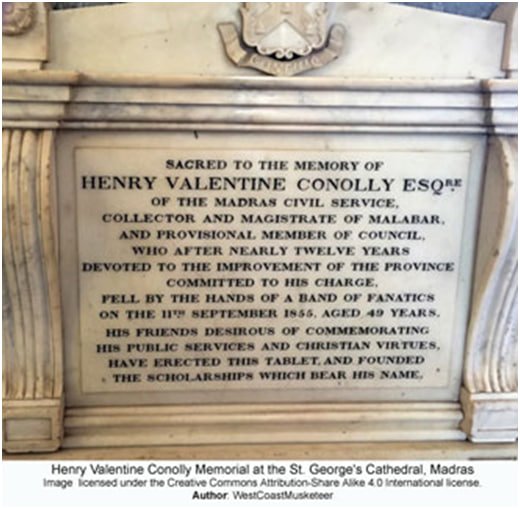

59. Henry Valentine Conolly

60. Miscellaneous notes

61. Culture of the land

62. The English efforts

63. Famines

64. Oft-mentioned objections

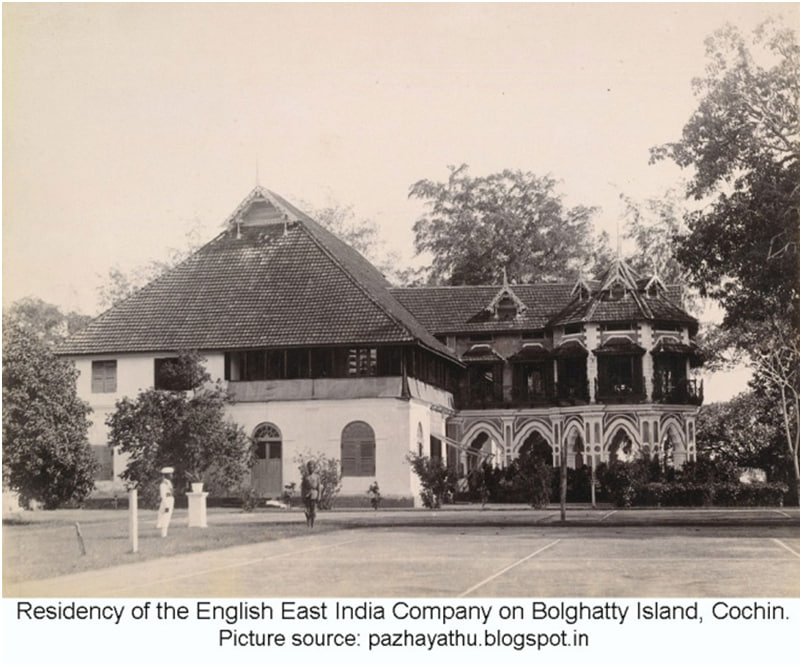

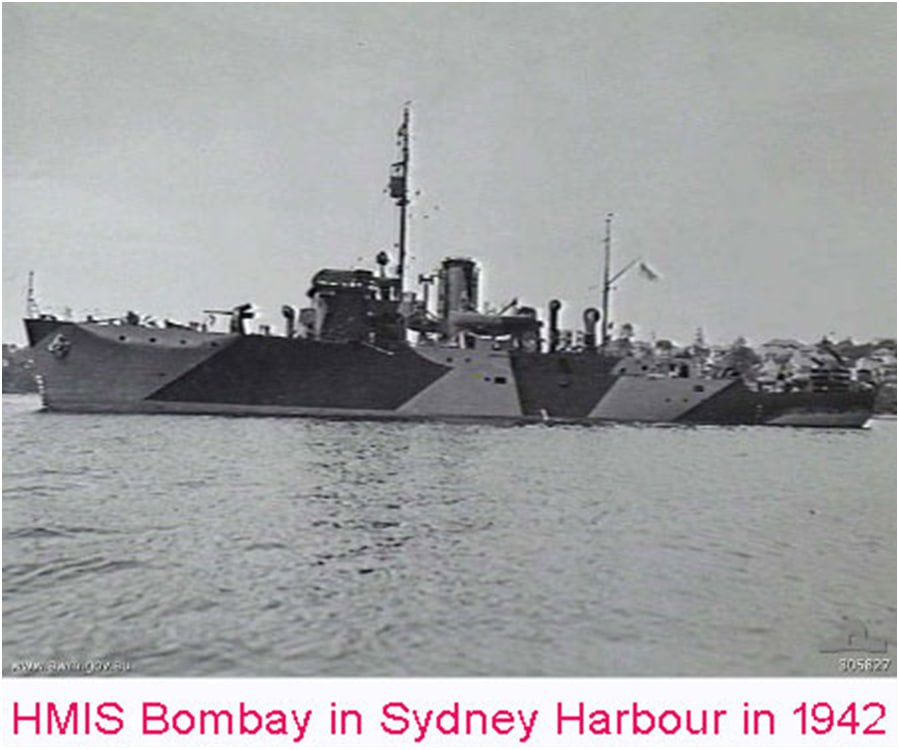

65. Photos and picture of the Colonial times

66. Payment for the Colonial deeds

67. Calculating the compensation

CLICK HERE

Go to Malabar Manual

Please note that on a computer browser, ALT & Back arrow, will be move the page to previous view / location. On mobile devices, touching the Back arrow found on the bottom of the screen will move the page to the previous view / locatioon.

COMMENTARY CONTENTS

Cover page

Book profile

Ancient quotes relevent to South Asia

1. My aim

2. The information divide

3. The layout of the book

4. My own insertions

5. The first impressions about the contents

6. India and Indians

7. An acute sense of not understanding

8. Entering a terrible social system

9. The doctoring and the manipulations

10. Missed or unmentioned, or fallacious

11. NONSENSE

12. Nairs / Nayars

13. A digression to Thiyyas

14. Designing the background

15. Content of current-day populations

16. Nairs / Nayars

17. The Thiyya quandary

18. The terror that perched upon the Nayars

19. The entry of the Ezhavas

20. Converted Christian Church exertions

21. Ezhava-side interests

22. The takeover of Malabar

23. Keralolpathi

24. About the language Malayalam

25. Superstitions

26. Misconnecting with English

27. Feudal language

28. Claims to great antiquity

29. Piracy

30. Caste system

31. Slavery

32. The Portuguese

33. The Dutch

34. The French

35. The ENGLISH

36. Kottayam

37. Mappillas

38. Mappilla outrages on Nayars & Hindus

39. Mappilla outrage list

40. What is repulsive about the Muslims?

41. Hyder Ali

42. Sultan Tippu

43. Women

44. Laccadive Islands

45. Ali Raja

46. Kolathiri

47. Kadathanad

48. The Zamorin and other apparitions

49. The Jews

50. Social customs

51. Hinduism

52. Christianity

53. Pestilence, famine etc.

54. British Malabar vs. Travancore kingdom

55. Judicial

56. Revenue and administrative changes

57. Rajas

58. Forests

59. Henry Valentine Conolly

60. Miscellaneous notes

61. Culture of the land

62. The English efforts

63. Famines

64. Oft-mentioned objections

65. Photos and picture of the Colonial times

66. Payment for the Colonial deeds

67. Calculating the compensation

a. Bringing in peace and civility

b. Emancipation of slaves

c. Educating the peoples

d. A huge egalitarian administrative system

e. Postal Department

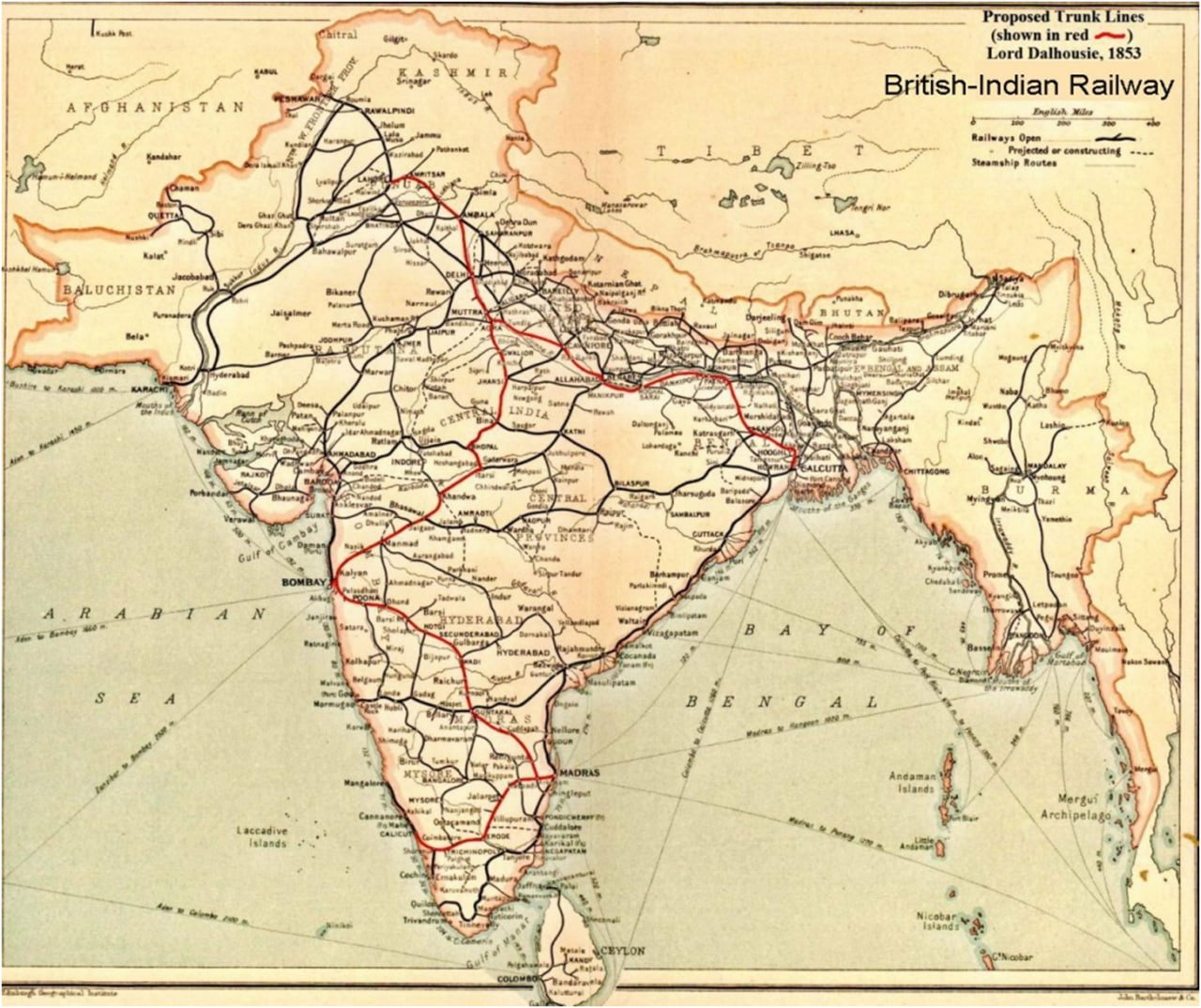

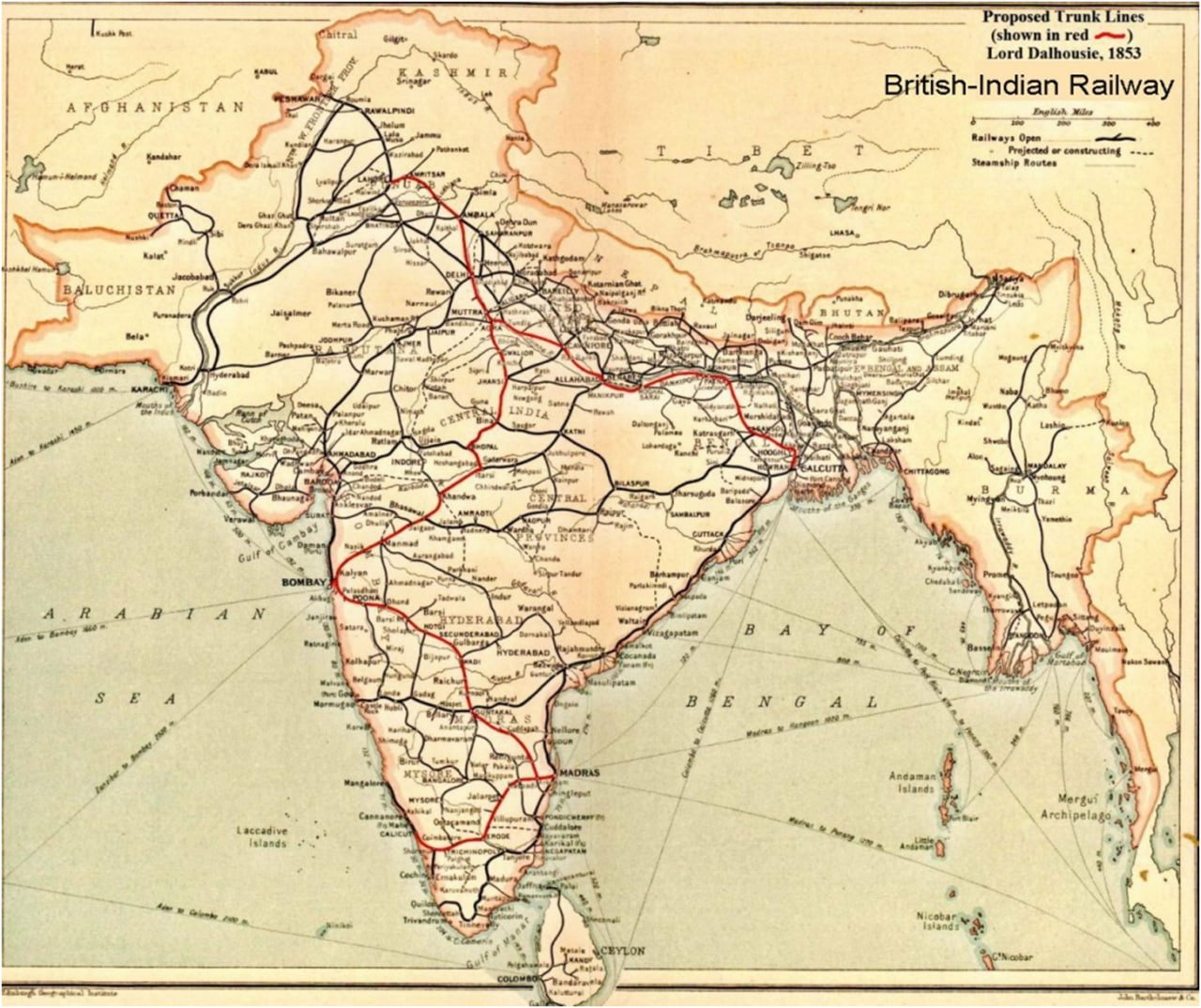

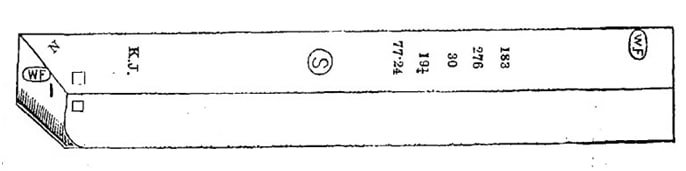

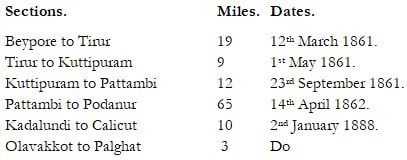

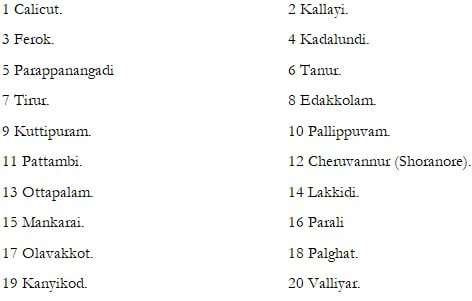

f. Railways

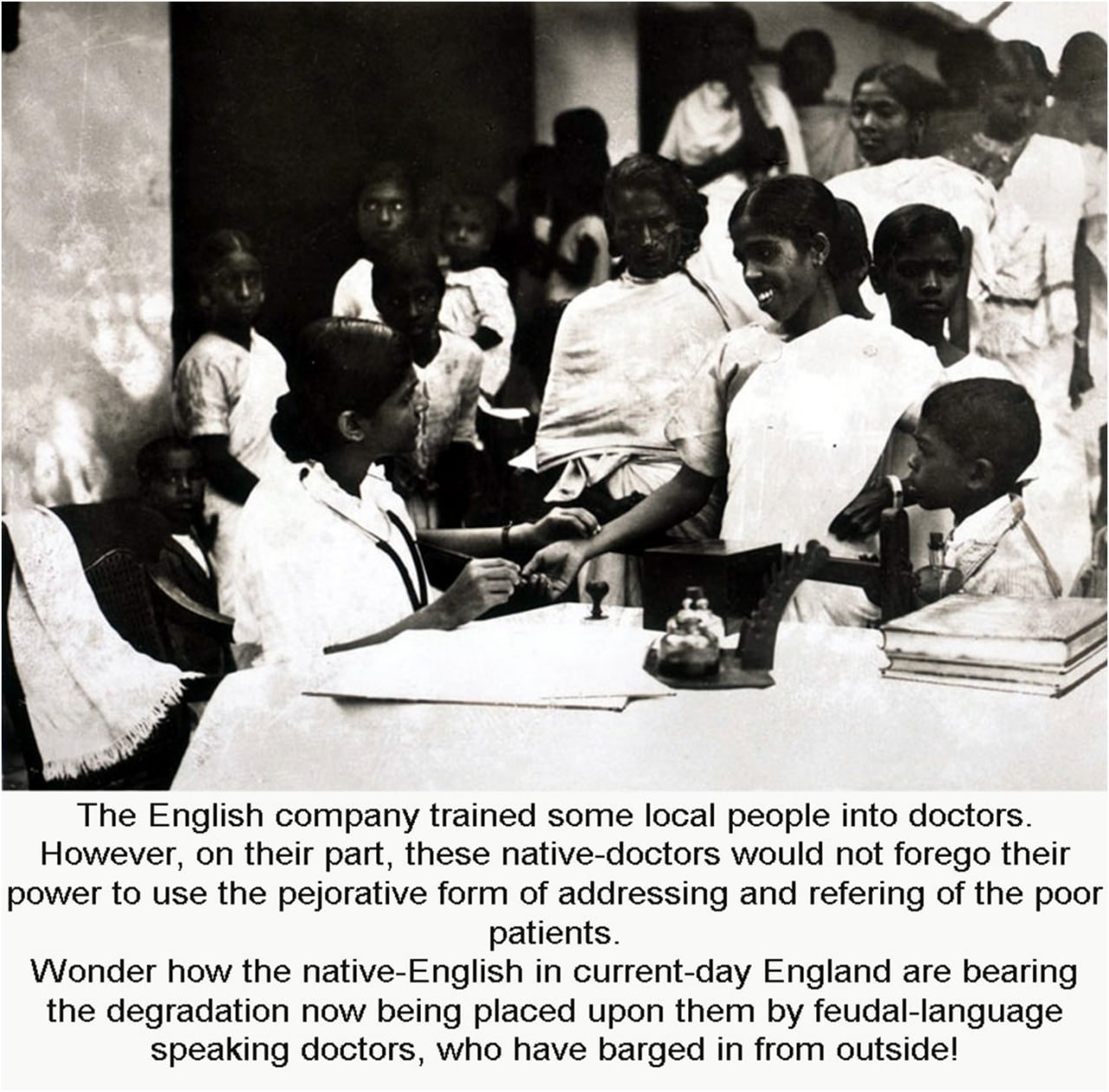

g. Hospitals and public healthcare

h. Judiciary

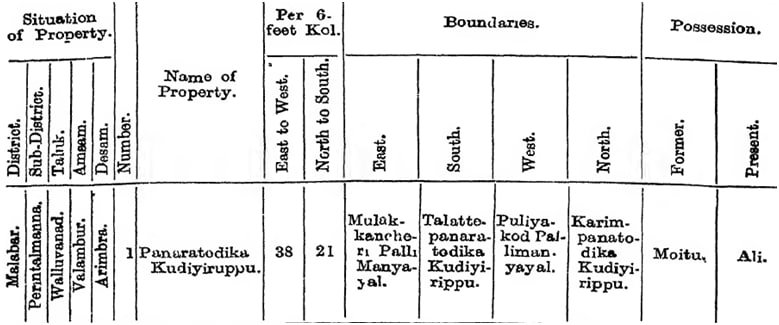

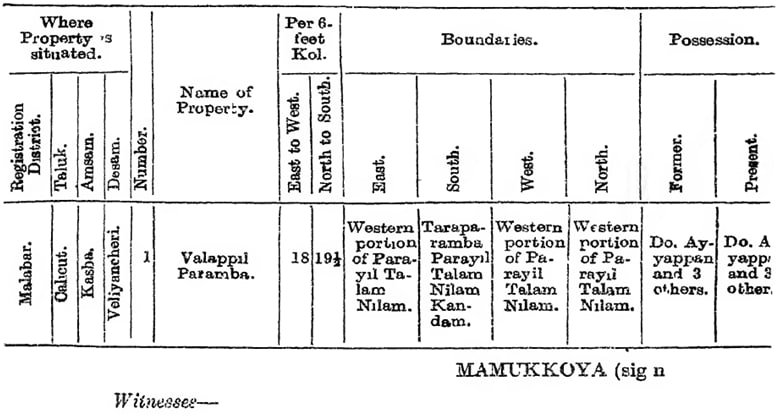

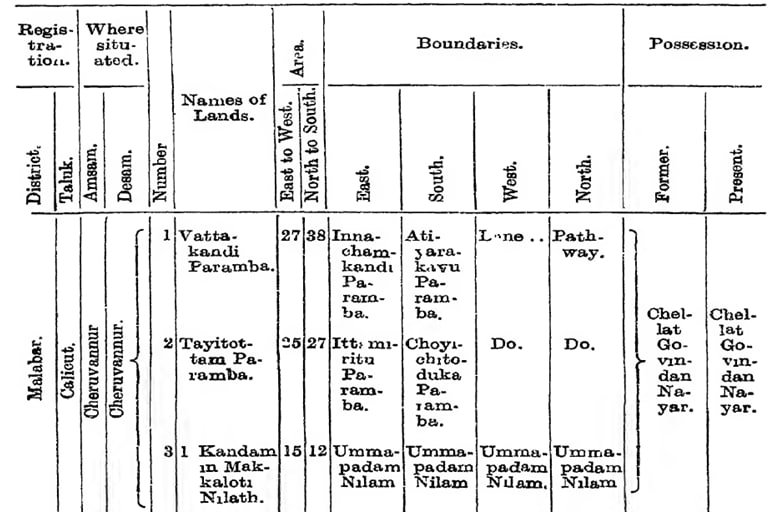

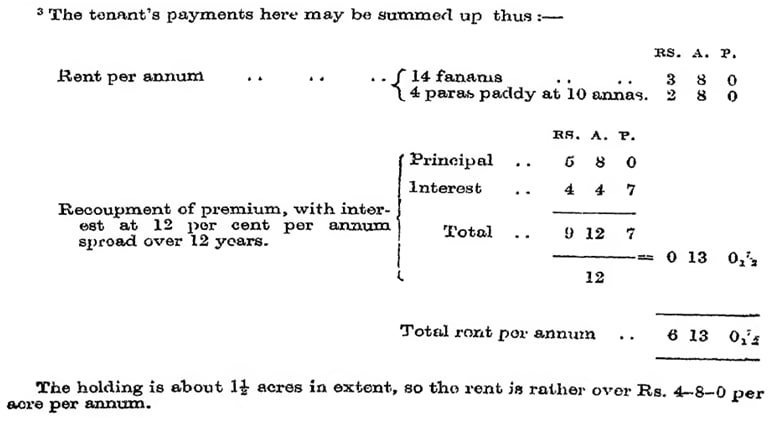

i. Land Registration Department

j. Police department

k. Public Service Commissions

l. Free trade routes

m. Sanitation

n. Public Conveniences

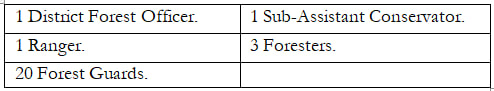

o. Forest Department

p. Indian army

q. Miscellaneous

r. Statutory councils, rules, decorum &c.

s. Now, let us speak about concepts.

t. Roadside trees

u. Freedom of press

v. Overrunning independent kingdoms

w. People quality enhancement

Complete list of Compensation dues

b. Emancipation of slaves

c. Educating the peoples

d. A huge egalitarian administrative system

e. Postal Department

f. Railways

g. Hospitals and public healthcare

h. Judiciary

i. Land Registration Department

j. Police department

k. Public Service Commissions

l. Free trade routes

m. Sanitation

n. Public Conveniences

o. Forest Department

p. Indian army

q. Miscellaneous

r. Statutory councils, rules, decorum &c.

s. Now, let us speak about concepts.

t. Roadside trees

u. Freedom of press

v. Overrunning independent kingdoms

w. People quality enhancement

Complete list of Compensation dues

Last edited by VED on Fri Feb 16, 2024 4:29 pm, edited 50 times in total.

1. My aim

1 #

First of all, I would like to place on record what my interest in this book is. I do not have any great interest in the minor details of Malabar or Travancore. Nor about the various castes and their aspirations, claims and counterclaims.

My interest is basically connected to my interest in the English colonial rule in the South Asian Subcontinent and elsewhere. I would quite categorically mention that it is ‘English colonialism’ and not British Colonialism (which has a slight connection to Irish, Gaelic and Welsh (Celtic language) populations).

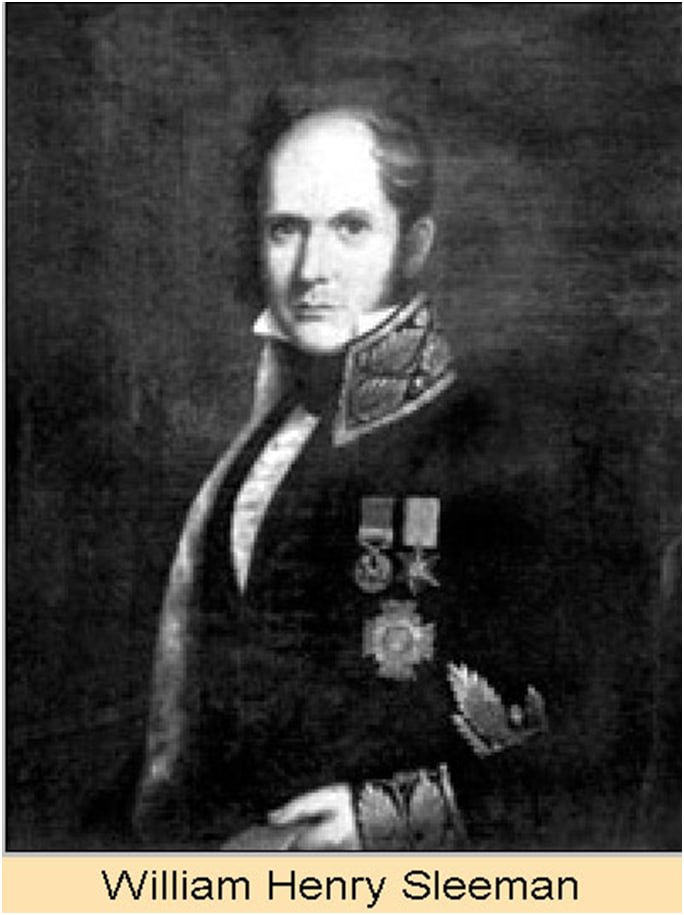

Even though I am not sure about this, I think the book Malabar was made as part of the Madras Presidency government’s endeavour to create a district manual for each of the districts of Madras Presidency. William Logan was a District Collector of the Malabar district of Madras Presidency. The time period of his work in the district is given in this book as:

6th June 1875 to 20th March 1876 (around 9 months) as Ag. Collector. From 9th May 1878 to 21st April 1879 (around 11 months) as Collector. From 23rd November 1880 to 3rd February 1881 (around 2 months) as Collector. Then from 23rd January 1883 to 17th April 1883 (around 3 months) as Collector. After all this, he is again posted as the Collector from 22nd November 1884.

In this book, the termination date of his appointment is not given. Moreover, I have no idea as to why he had a number of breaks within his tenure as the district Collector of Malabar district.

Since this book is seen as published on the 7th of January 1887, it can safely be assumed that he was working on this book during his last appointment as Collector on the 22nd of November 1884.

From this book no personal information about William Logan, Esq. can be found out or arrived at.

It is seen mentioned in a low-quality content website that he is a ‘Scottish officer’ working for the British government. Even though this categorisation of him as being different from British subjects / citizens has its own deficiencies, there are some positive points that can be attached to it also.

He has claimed the authorship of this book. There are locations where other persons are attributed as the authors of those specific locations. Also, there is this statement: QUOTE: The foot-notes to Mr. Græmo’s text are by an experienced Native Revenue Officer, Mr. P. Karunakara Menon. END OF QUOTE.

The tidy fact is that the whole book has been tampered with or doctored by many others who were the natives of this subcontinent. Their mood and mental inclinations are found in various locations of the book. The only exception might be the location where Logan himself has dealt with the history writing. More or less connected to the part where the written records from the English Factory at Tellicherry are dealt with.

His claim, asserted or hinted at, of being the author of the text wherein he is mentioned as the author is in many parts possibly a lie. In that sense, his being a ‘Scottish officer’, and not an ‘English officer’ might have some value.

The book Malabar ostensibly written by William Logan does not seem to have been written by him. It is true that there is a very specific location where it is evident that it is Logan who has written the text. However, in the vast locations of the textual matter, there are locations where it can be felt that he is not the author at all.

There are many other issues with this book. I will come to them presently. Let me first take up my own background with regard to this kind of books and scholarly writings.

I need to mention very categorically that I am not a historian or any other kind of person with any sort of academic scholarship or profundity. My own interest in this theme is basically connected to my interest in the English colonial administration and the various incidences connected to it.

I have made a similar kind of work with regard to a few other famous books. I am giving the list of them here:

1. Travancore State Nanual by V Nagam Aiya

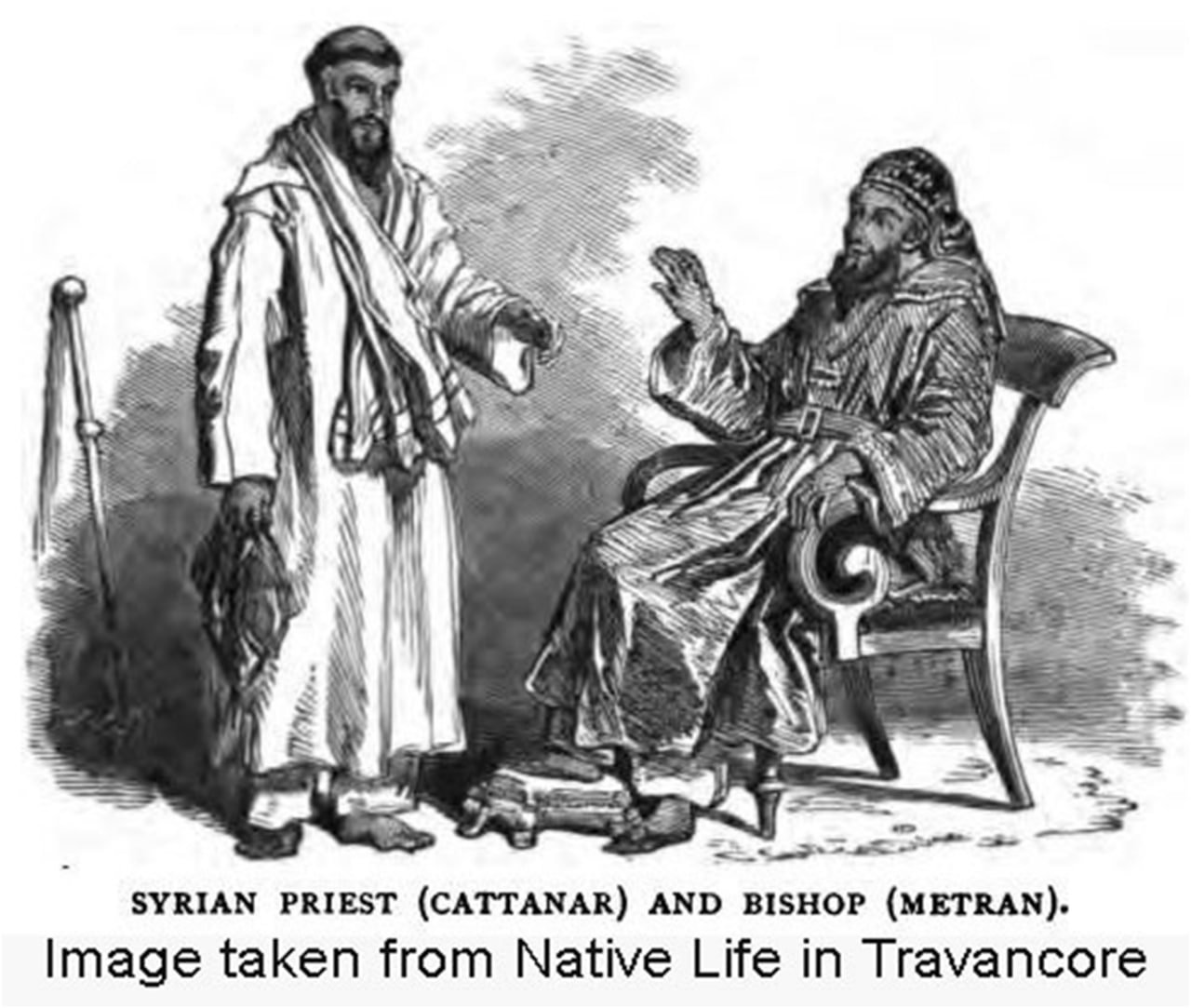

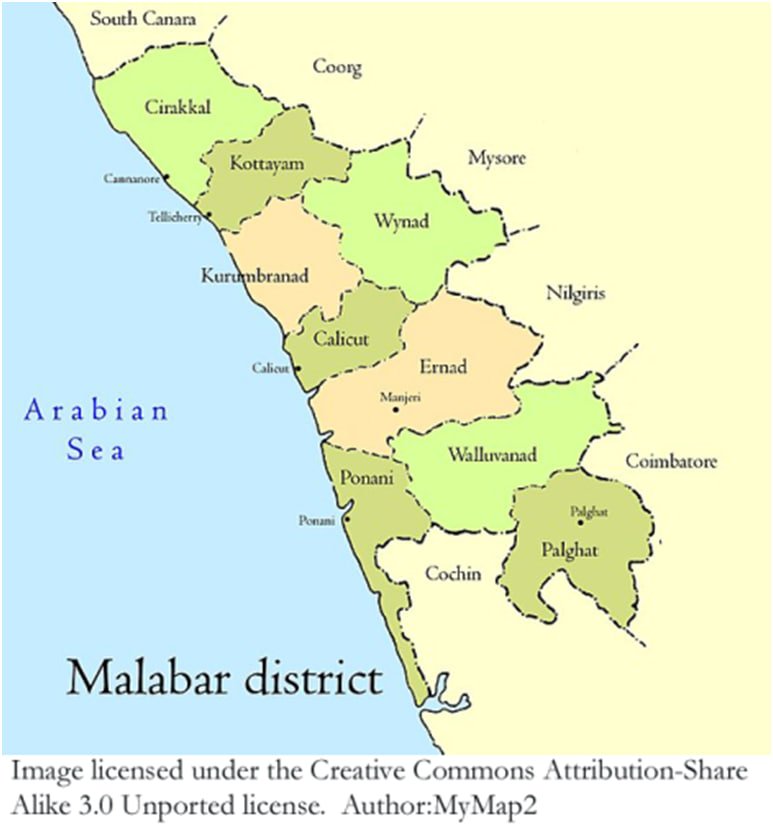

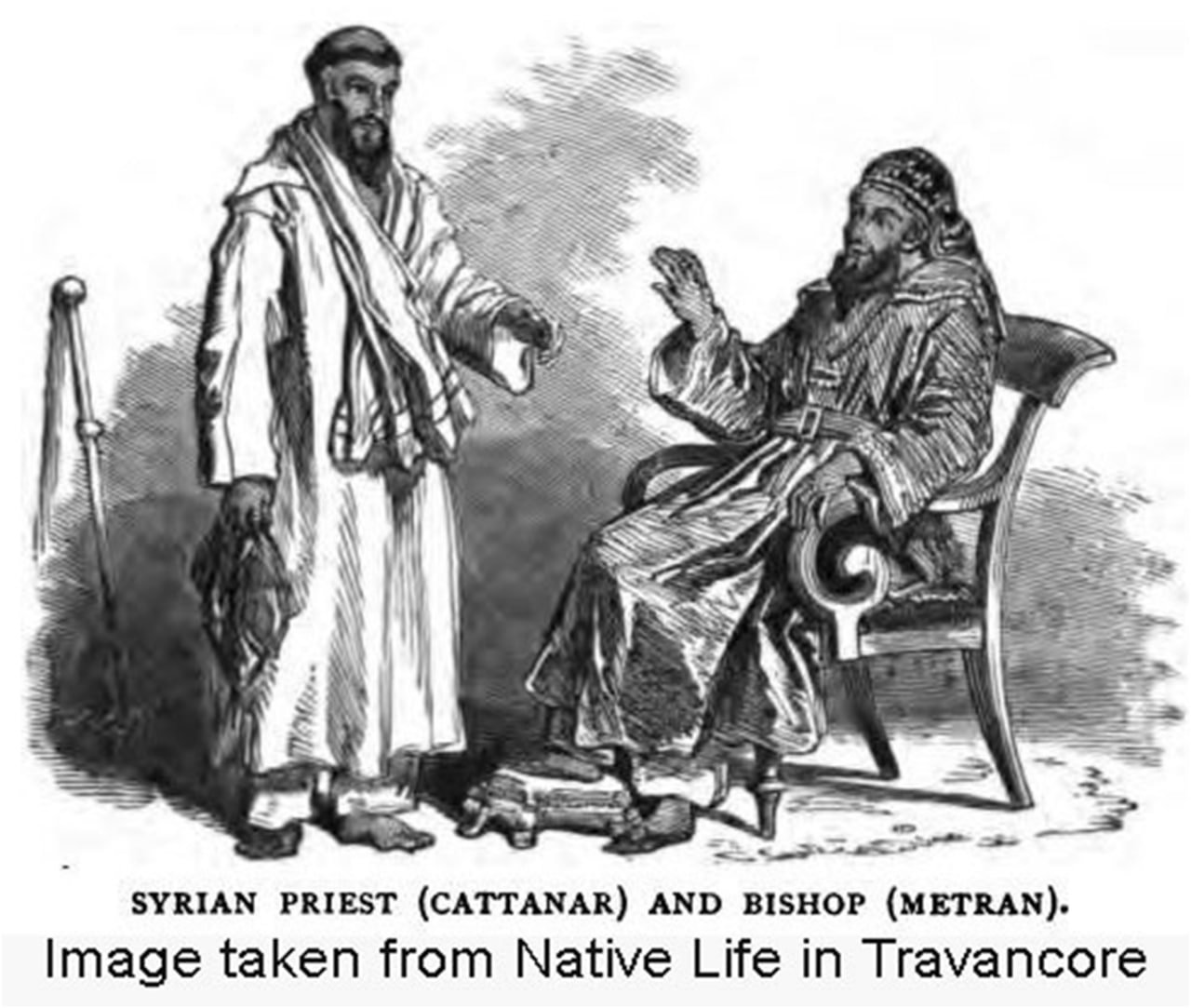

2. Native Life in Travancore by Rev. Samuel Nateer F.L.S

3. Castes & Tribes of Southern India Vol 1 by Edgar Thurston

4. Omens and superstitions of southern India by Edgar Thurston

5. The Native races of South Africa by George W. Stow, F.G.S., F.R.G.S.

6. Oscar Wilde and Myself by Alfred Bruce Douglas

7. Mein Mampf by Adolf Hitler – a demystification!

Of the above books, the first six I have recreated into much readable digital books. After that I added a commentary on the contents of each book.

For the fifth book, I have only written a commentary. No attempt was made to recreate it into a more readable digital book. For, the book is available elsewhere in many formats in very highly readable forms. Both digital as well as print version.

Why I have mentioned this much about the way I work on these books is to convey the idea that when I work on a book to create a readable digital version, I get to read the text, invariably.

In the case of this book, Malabar, I have gone through each line and paragraph. It is possible that I have missed a lot of errors in my edited version. For, I did not get ample time to proofread. For, taking out the text from very faint, scanned versions of the original book was a very time-taking work. The work was tedious. And apart from that, getting to reformat the text is an extremely slow-paced work.

But the word-by-word working on the text gave me the opportunity to go through the text in a manner which no casual reader might do. I could enter in almost every nook and corner of the textual matter. And many minor, and yet significant information have come into my notice.

Since I have done a similar work on Travancore State Manual by V Nagam Aiya and on Native Life in Travancore by Rev. Samuel Mateer, I have had the opportunity to understand the contemporary happenings of those times in the next door native-king ruled kingdom of Travancore.

Apart from all that, I do personally have a lot of information on this landscape and how it experienced and reacted to the English rule. It goes without saying that the current-day formal history assertions about the English colonial rule are totally misleading and more or less absolute lies. Even the geographical frame on which this history has been built upon is wrong and erroneous.

I have been hearing the words to the effect: Logan said this or that in his Malabar Manual, on many things concerning the history and culture of Malabar. However, it was only in this year, that is, 2017, that I got a full page copy of his Two volume book.

Even though this book is named Malabar, it is generally known as the Malabar Manual in common parlance. I think this is due to the fact that this book must have been a part of the District Manuals of Madras (circa 1880), which were written about the various districts, which were part of the Madras Presidency of the English-rule period in the Subcontinent. In fact, this is the understanding one gets from reading a reference to this book in Travancore State Manual written by V Nagam Aiya. In fact, Nagam Aiya says thus about his own book: ‘I was appointed to it with the simple instruction that the book was to be after the model of the District Manuals of Madras’.

I initiated my work on this book without having any idea as to what it contained, other than a general idea that it was a book about the Malabar district of Madras Presidency.

However, as I progressed with the work and the reading, a very ferocious feeling entered into me that this is a very contrived and doctored version of events and social realities. In the various sections of the book, wherein there is no written indication that it is not written by Logan, I have very clearly found inclinations and directions of leanings shifting. In certain areas, they are totally opposite to what had been the direction of leaning in a previous writing area.

It is very easily understood that words do have direction codes not only in their code area, but also in the real world location. A slight change of adjective can shift the direction of loyalty, fidelity and fealty from one entity to another. A hue of a hint or suggestion can shift this direction. With a single word or adjective or usage, placed in an appropriate location with meticulous precision, an individual’s bearing and aspirations can be differently defined. An explanation for an action can shift from portraying it as grand to framing it as a gratuitous deed.

Only a very minor part of this book could be the exact textual input of William Logan. Other parts of the book which are not mentioned as of others can actually be the writings of a few others.

This book has been written for the English administrators. From that perspective, there would be no attempt on the part of William Logan to fool or deceive the English administrators, with regard to the realities of the inputs of English administration. This is the only location in this book, where everything is honest.

In all the other parts, half-truths, partial truths, partial lies, total lies and total suppression of information are very rampant. Moreover, there might even be total misrepresentation of events and populations. The natives of the subcontinent who have very obviously participated in the creation of this book have made use of the opportunity presented to them to insert their own native-land mutual jealousies, repulsions, antipathies etc. in a most subtle manner. This very understated and very fine and slender manner of inserting errors into the textual content has been resorted to, just to be in sync with the general gentleness of all English colonial stances.

That was the first attempt at doctoring the contents of this book.

There was again a second attempt at doctoring the contents of this book. That was in 1951. On reading the text itself I had a terrific feeling that some terrible manipulation and doctoring had been accomplished on this book much after it had been first published in 1887. For, this book was actually an official publication of the British colonial administration in the Madras Presidency. However, the flavour of a British / English colonial book was not there in the digital copy of the book which I had in my hands. This copy had been a re-edited and reprinted work, published in 1951.

Some very fine aura of an English colonial book was seen to have been wiped out. Even though it could be quite intriguing as to why an original book had to be edited and various minor but quite critical changes had been inserted into this book, there are very many reason that why such malicious actions have been done. In fact, after the formation of three nations inside the South Asian Subcontinent, there have been many kinds of manipulations on the recorded history of the location. This has been done to suit the policy aims of the low-class nations that have sprung up in the region.

On checking the beginning part of the book, I found this writing:

QUOTE: In the year 1948, in view of the importance of the book, the Government ordered that it should be reprinted. The work of reprinting was however delayed, to some extent, owing to the pressure of work in the Government Press. While reprinting the spelling of the place names have, in some cases, been modernized.

Egmore, B. S. BALIGA,

17th September 1951 Curator, Madras Record Office

END OF QUOTE

So, that much admission from a government employee is there.

A few decades back, I was staying in a metropolitan city of India. This city had been the headquarters of one of the Presidencies of British-India. I need to explain what a Presidency is. For there might be readers who do not understand this word.

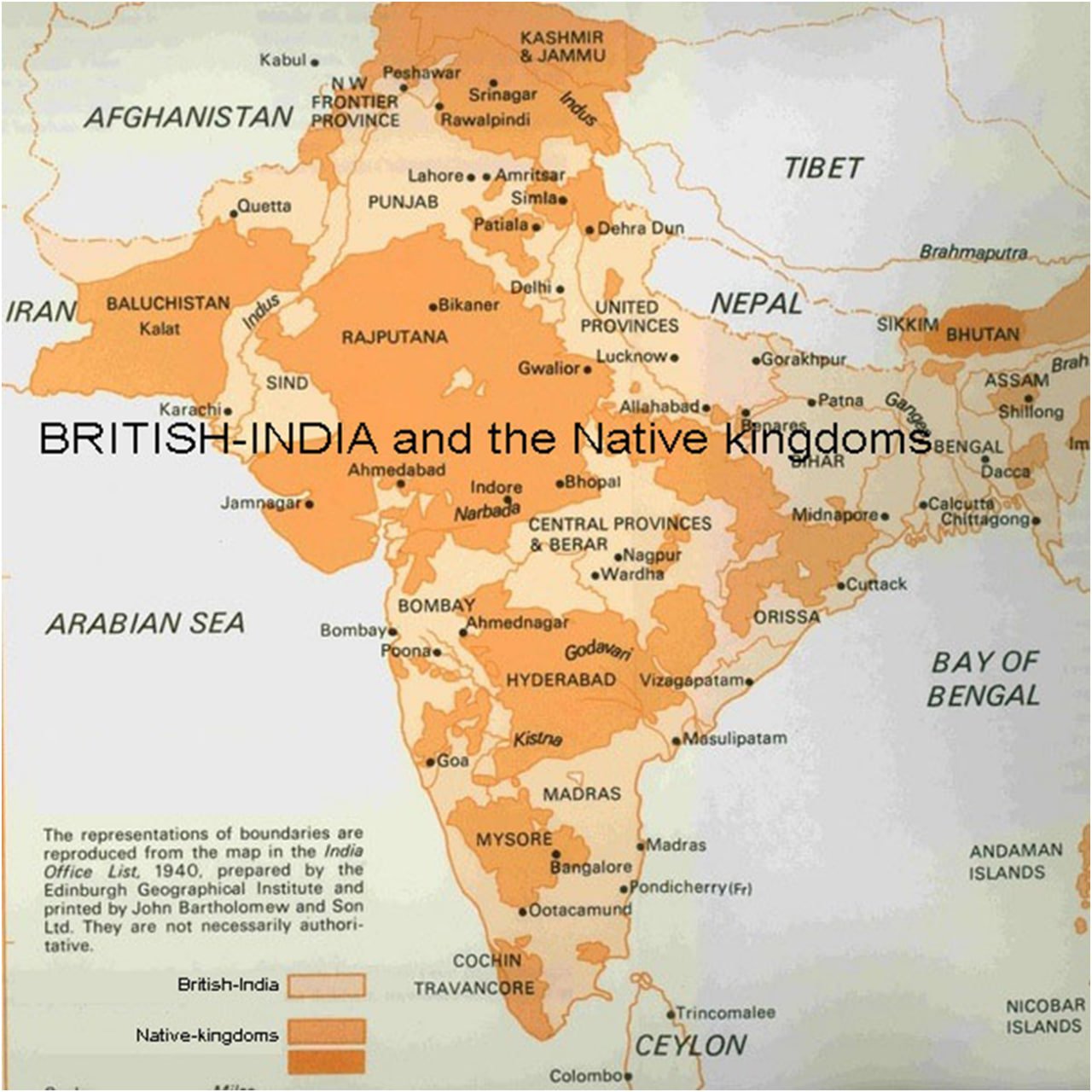

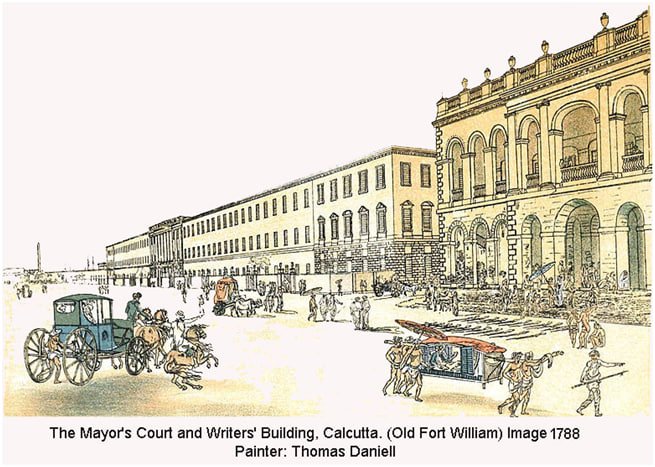

The English colonial rule in the South Asian Subcontinent actually was centred on three major cities. Bombay, Madras and Calcutta. Even though the colonial rule is generally known as British-rule and the location as British-India, there are certain basic truths to be understood. The so-called British-rule was more or less an English-rule, centred on a rule by England. It was not a Celtic language or Celtic population rule.

William Logan, who purports to be the author of this book, is not an Englishman. So to that extent, he is removed from the actual fabulous content of the English-rule in the subcontinent.

The second point to mention is that even though there is a general misunderstanding that the whole of the subcontinent was part of British-India and British-Indian administration, the rough truth is that most of the locations outside the afore-mentioned three Presidencies were not part of British-India or British-Indian administration.

However, due to the extremely fabulous content quality of the British-Indian administration, as well as the quaint refined quality, dignified way of behaviour, honourableness, sense of commitment and dependability of the English administration, all the other native-kingdoms which existed in the near proximity of the Presidencies inside the subcontinent, more or less adhered intimately to British-India without any qualms. For, there are no self-depreciating verbal usages of servitude in English. In the native feudal-languages of the location, such a connection would have affected their stature very adversely in the verbal codes. [Please read the chapter on Feudal Languages in this Commentary)

In the local culture, the exact traditional history is that of backstabbing, treachery, usurping of power, going back on word, double-crossing &c. When a very powerful political entity appeared on the scene, which was seen quite bereft of all these sinister qualities, everyone understood that it was best to connect to this entity.

However, this was to lead these kingdoms to their disaster and doom later on. For, a general feeling spread that all these kingdoms were part of British-India. Even in England this was the general feeling. An extremely disparaging usages such as ‘Princely state’ and ‘Indian Prince’ came to be used in English language to define them, due to this misunderstanding.

Actually the independent kingdoms were not ‘Princely states’. Nor were their kings mere ‘Indian princes’. They were kings. For instance, Travancore was not a Princely State. It was an independent kingdom. It was true that it was in alliance with British-India. To use this term ‘alliance’ to mention Travancore as bereft of its own sovereignty, is utter nonsense.

For, it is like saying that Kuwait is part of USA just because it is under the US protection. Or Japan, and many other similar low-class nations, which have made use of a close contact with the US to bolster up their own nations.

Travancore did mention its own stature as an independent kingdom very forcefully in a legal dispute with the Madras government.

Dewan Madava Row wrote thus to the government of the Madras Presidency in 1867: QUOTE:

(1 The jurisdiction in question is an inherent right of sovereignty

(2 The Travancore State being one ruled by its own Ruler possesses that right

(3 It has not been shown on behalf of the British Government that the Travancore State ever ceded this right because it was never ceded, and

END OF QUOTE

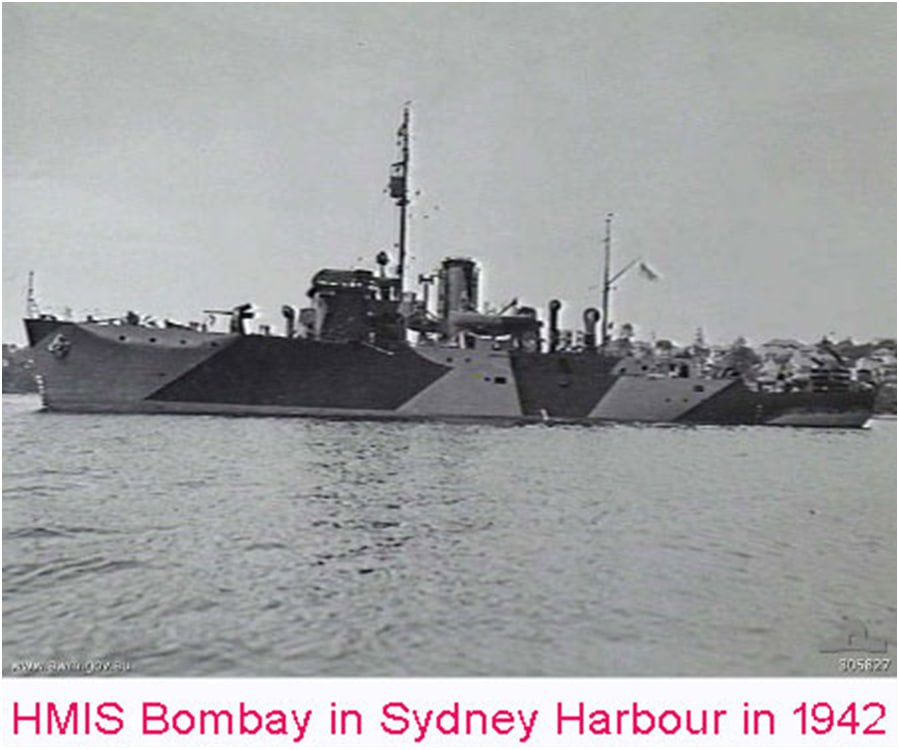

However, for the independent kingdoms in the subcontinent, this close connection with British-India later turned out to be a suicidal stranglehold. For, in the immediate aftermath of World War 2, a total madman and insane criminal became the Prime Minister of Britain. In his totally reckless administration that lasted around five years, he tumbled down the English Empire, all over the world.

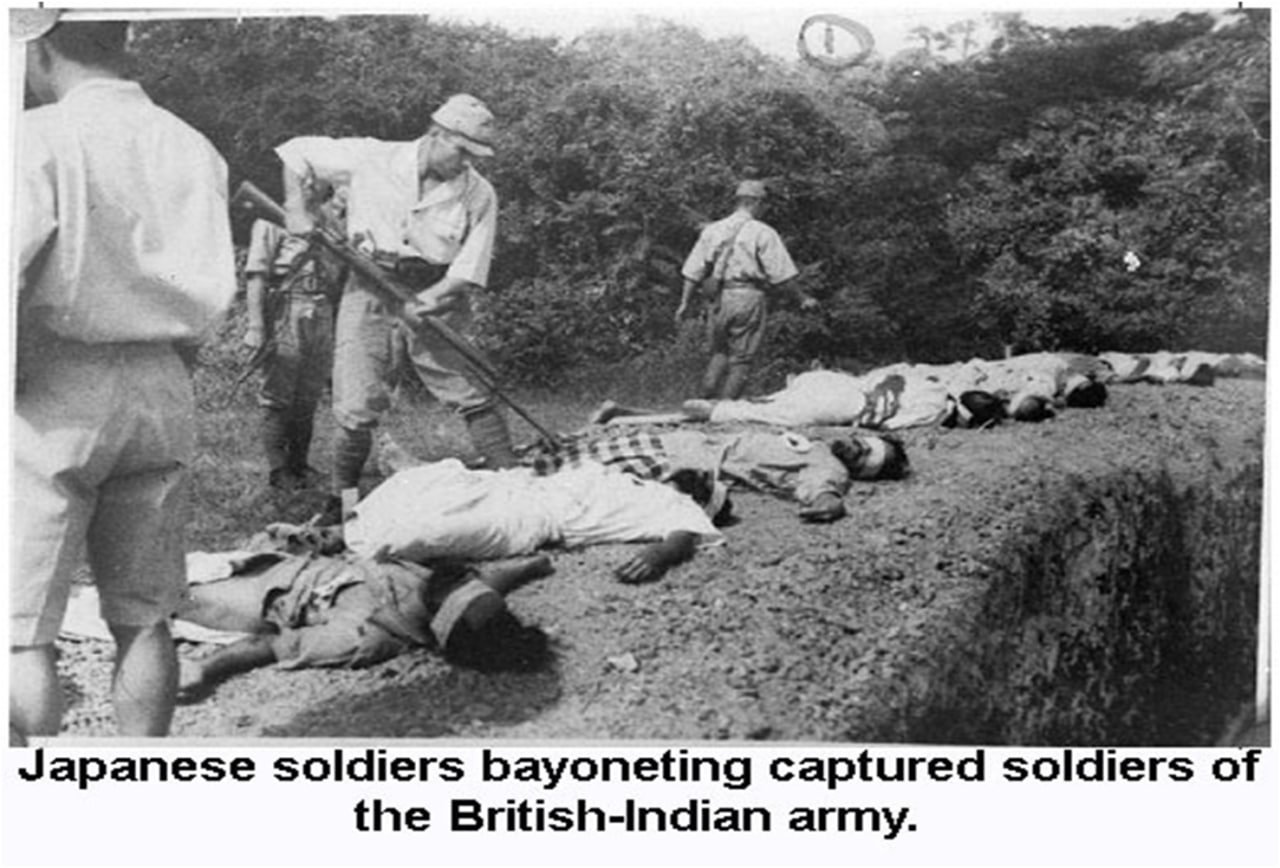

In the South Asian subcontinent, the British-Indian army was divided into two and handed over to two politicians who had very good connection to the British Labour Party leaders.

These two leaders used the might of the British-Indian army which had come into their own hands to more or less run roughshod over all the native-kingdoms of the subcontinent. They were all forcefully added to the two newly-created nations, Pakistan and India. This action might need to be discussed from a very variety of perspectives. However, this book does not aim to go into that detail.

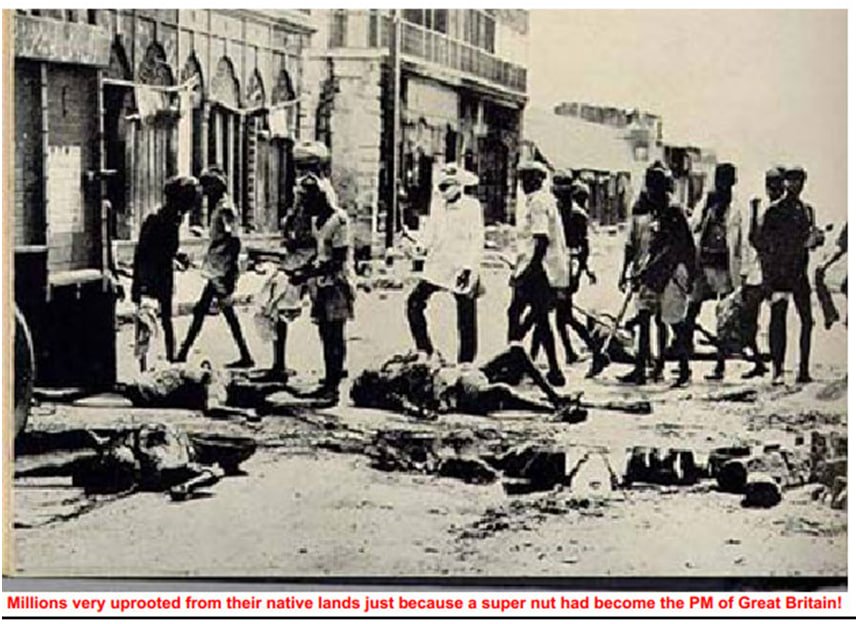

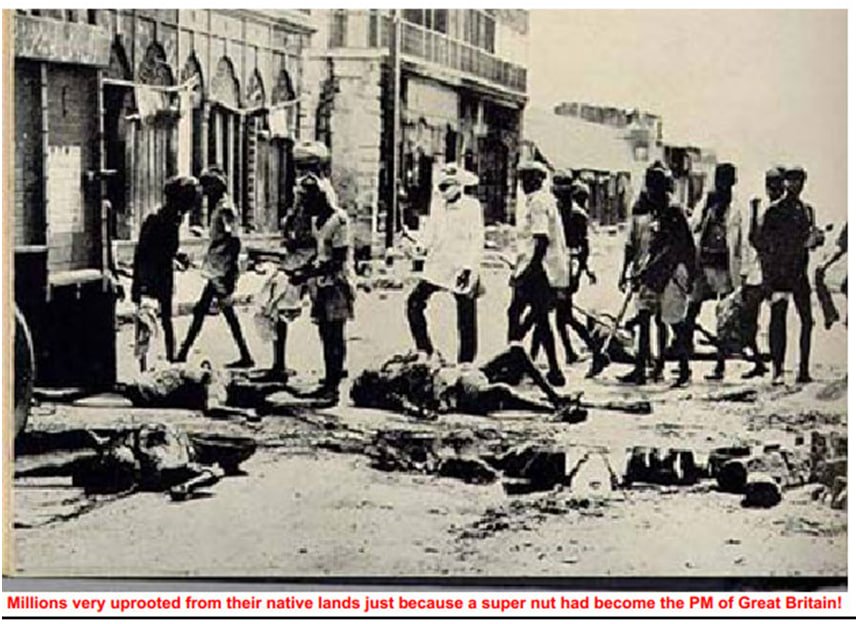

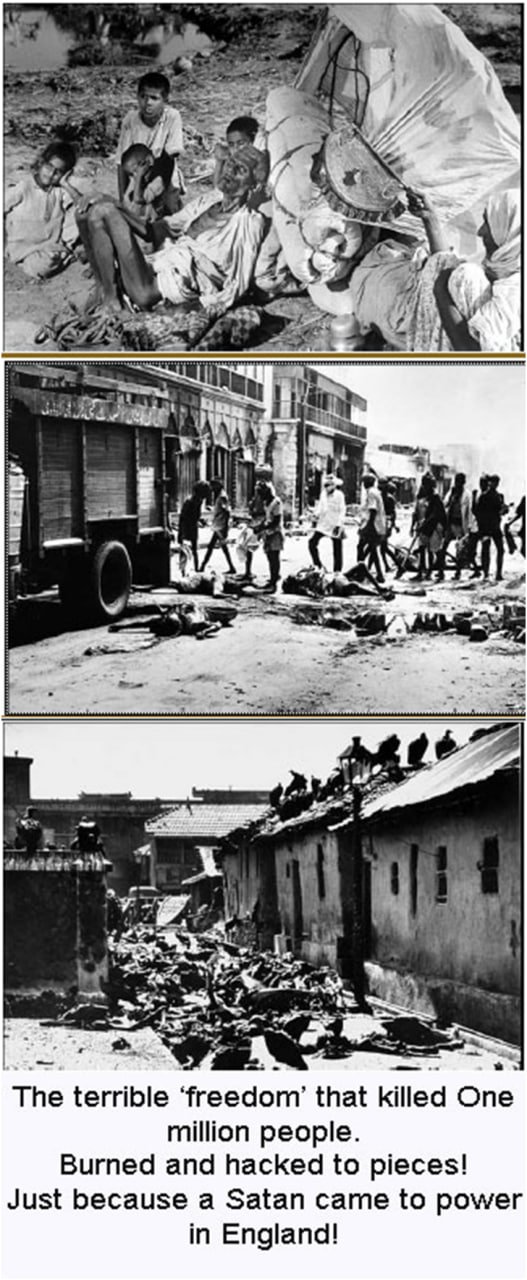

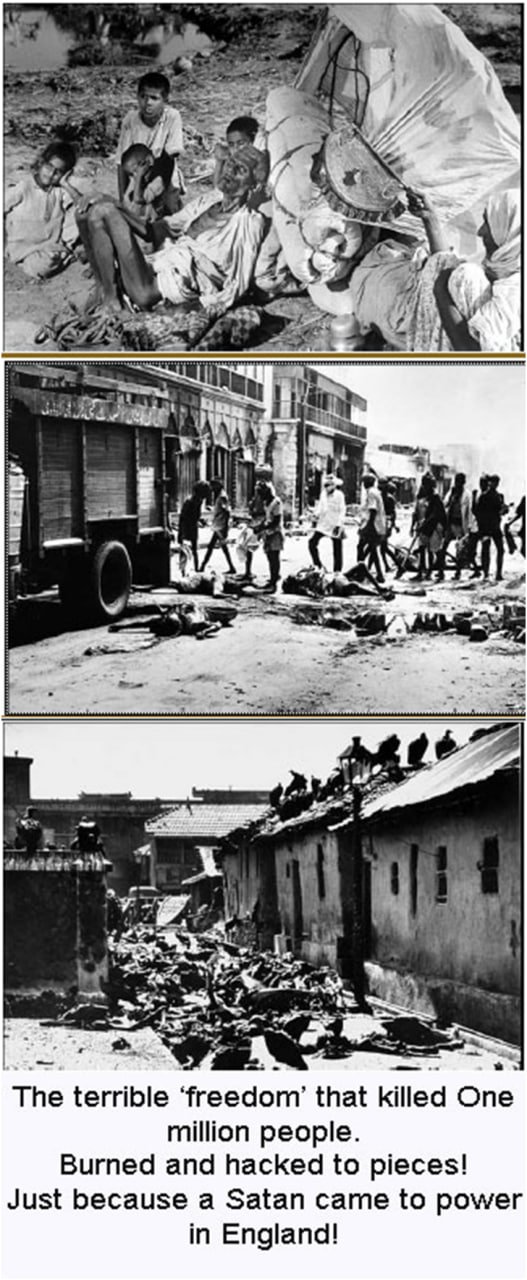

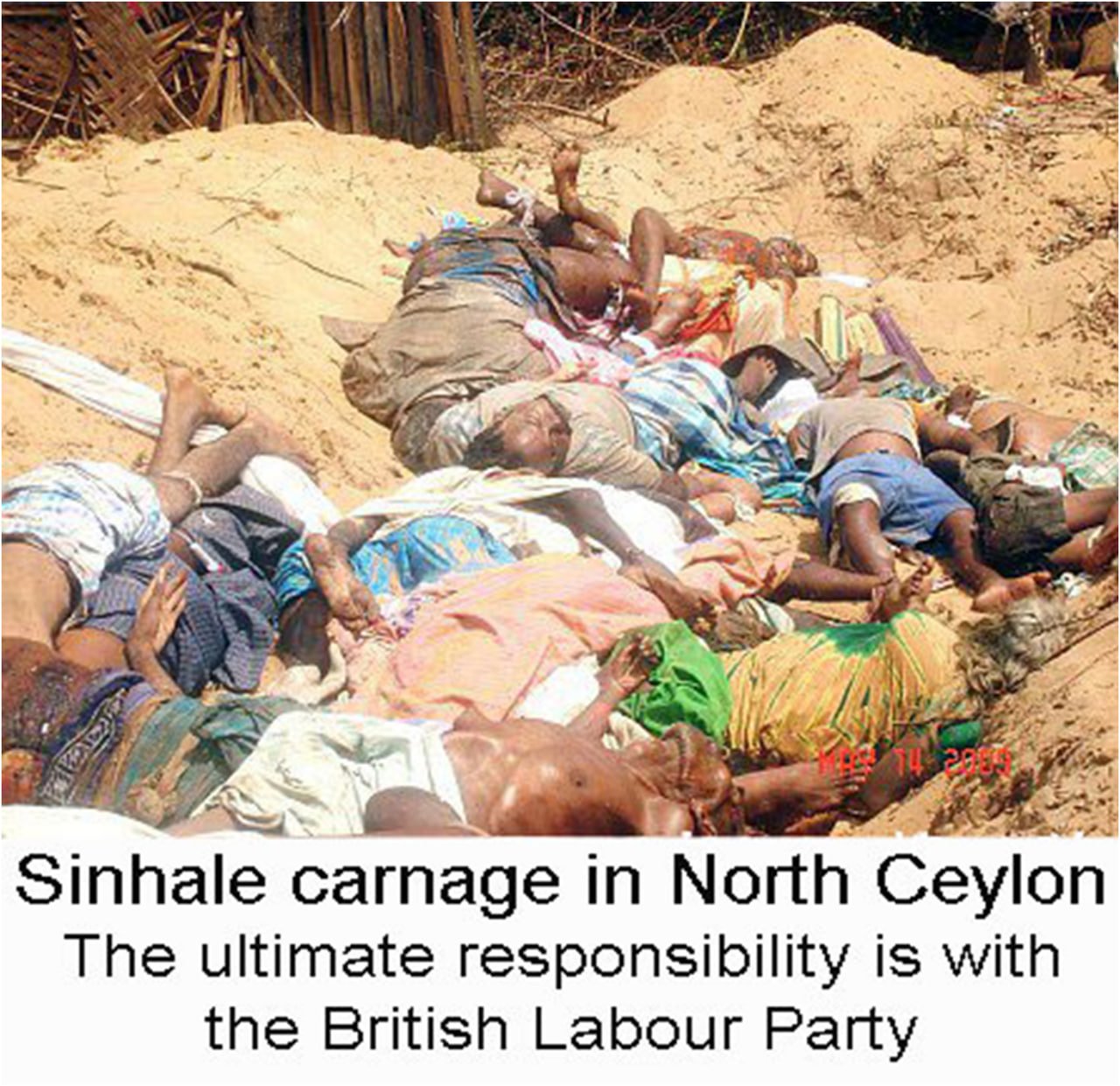

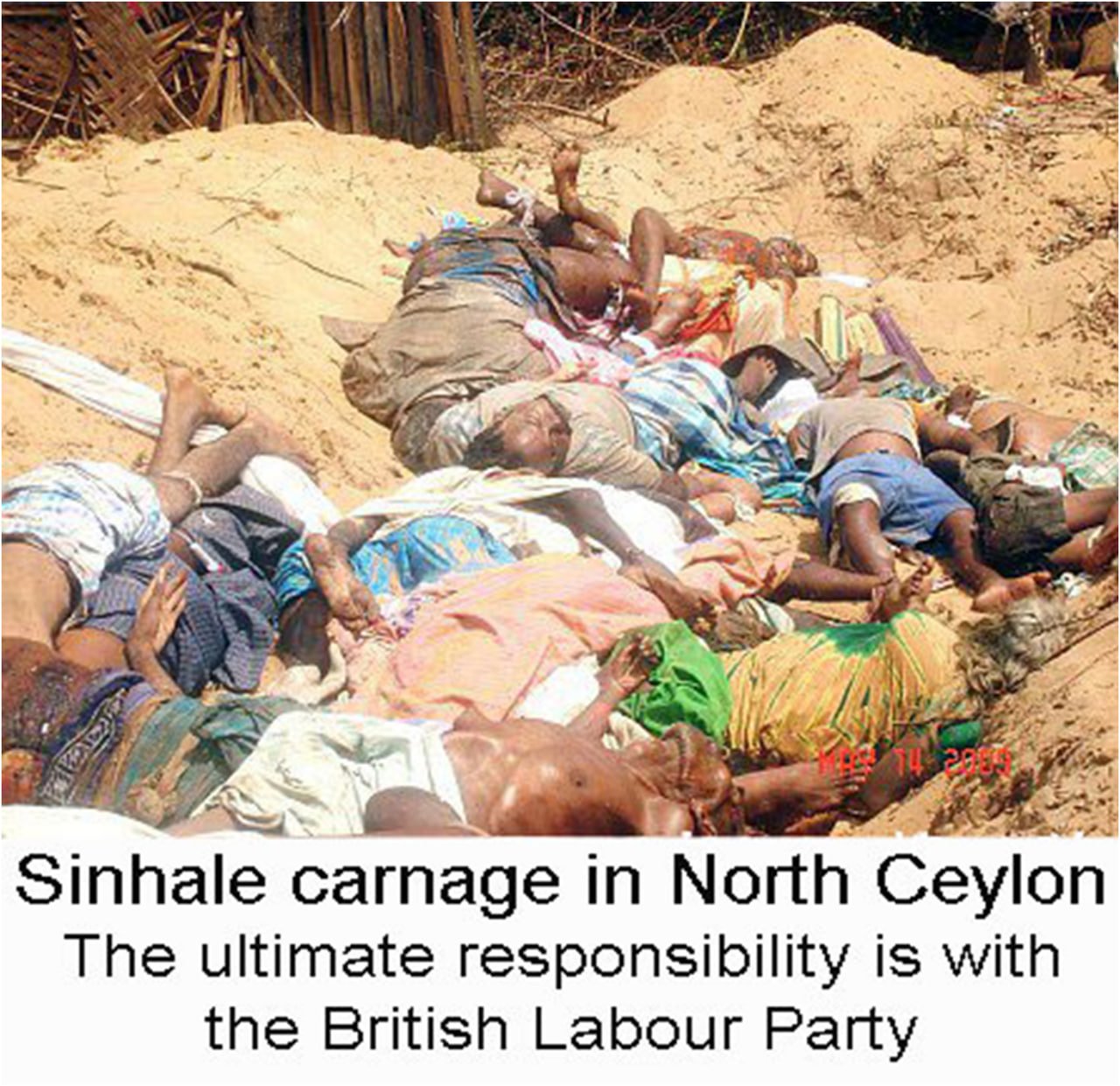

However, the dismantling of the English-rule was disastrous to the people. In the northern parts of the subcontinent, which is mainly the Hindi hinterland, a communal confrontation took place between the Muslims and the non-Muslim populations. Around 10 lakh (1 million) people were slaughtered. Burned, and hacked. Towns and villages which had lived in total peace and prosperity under the English-rule became battlegrounds. No house or household was safe. People had the heartbreaking experience of seeing their youngsters broken down physically.

This was how the two nations of Pakistan and India were founded. Compared to the other parts of the subcontinent, the average social-quality of Hindi-speakers is low. This itself is a very fabulous illustrative point. For, on seeing Hindi films one might get a feeling that the Hindi-speakers are of a very resounding quality. Even native-English nations are being befooled by the Bombay (Hindi) film world, with the cunning use of fabulous Hindi films.

However, the truth remains that all over the subcontinent, including Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, the lower-placed sections of the feudal-language speaking sections of the populations do suffer from a mental and social suppression that cannot be seen or understood in English.

Now coming back to the madman who dismantled the English-Empire in the subcontinent and elsewhere, I personally do not know what retribution he received from providence. However, for the terrible suffering he let loose all around the world in general and in the South Asian Subcontinent in particular, he deserves to rot in hell till eternity. Not only him, but all those who support his evil deed also deserve just retribution from Nemesis.

Let me go back to the point I left. I was staying in a Metropolitan city in India which had been a headquarters city of one British-Indian Presidency, a few decades back. I was quite young. I had a casual conversation with an old man who had been a contemporary of the English-rule period in the city.

I asked him about the general quality of the Englishmen who had been officers in the administration. He said, they were all quite nice. But then, they were cut-off from the people. They had around them a coterie of natives of the subcontinent. These persons were generally the Hindus (Brahmins &c.) and other higher castes. There were lower castes also. However, all of them kept the native-English officers inside a social corridor which they controlled. They acted quite nice and coy to the native-English officers. But actually they were very cunning, and self-centred and had very obvious selfish interests.

This much this man told me. However, the vast amplitude of the information is like this:

The gullible native-English officers acted as per the advice of this cunning coterie. These cunning local vested-interest groups literally fed the native-English officials with their own native-land repulsions, caste hatred, antipathies and religious hatred. And also colluded with the native business interests to influence policy decisions in the sphere of economic and fiscal matters.

Even though, it is true that the native-English officers did in many instances see through their cunning intentions, it is not easy to detach completely from its snares. For, the most powerful weapon of luring and snaring an unwary adversary used in all feudal languages nations, is the weapon of hospitality, and effusive and quite overt friendliness.

In many cases, the native-English officials understood that a native of the subcontinent is at his most dangerous stance, when he acts most friendly and helpful. This is actually a part of the code-work inside feudal languages. I will deal with that later.

Now, why did I mention this idea here?

On reading the ‘Malabar’ written by William Logan, the impression that can spring spontaneously to my mind is of a very gullible native-English administration doing its best and giving its best to a population group which they cannot understand. Actually it is not one population group that they are dealing with. They are actually dealing with a series of population groups, each one them having its own aims and ambitions, which are totally different and antagonistic to various other groups. Even though the native-English go on insisting and try to define the native populations as belonging to one nation, there is no such an idea of a Nation-state in the minds of the populace.

In fact, the very idea of a nation-state is a mad insertion by the native-English.

William Logan was authorised to write this book. He had at his command a lot of native-officials up to the level of the Deputy District Collector to help him. He allowed them to write many notes and articles, which even though he must have edited, have all messed-up the quality of the information.

Logan has the feel of having been taken for a ride. But then, it can be understood that a lot of persons have worked on this book. For, there are a lot of tables and lists. All these can be understood to have been done by other persons. The book is quite huge. It has more than five hundred thousand words (more than 5 lakh words).

It contains a number of footnotes. Many of these foot-notes alludes to or point to or quotes from many ancient or scholarly books. Some of these books are the works of other language writers or travellers.

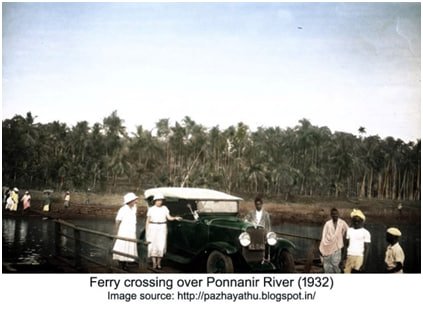

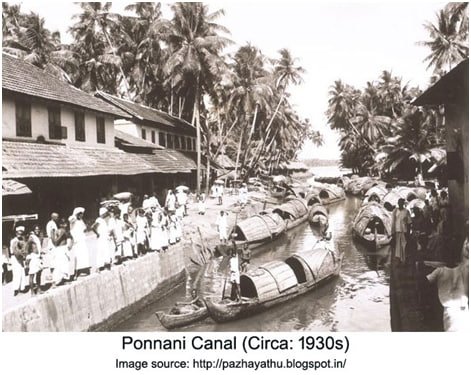

It is practically impossible for William Logan to have taken up these various books for reading and referring. Travelling in those days was quite a cumbersome action. There were many places where one could go only in a bullock cart.

Beyond all this, this book was written in a manuscript form in those days. There were no computers or any other digital gadgets available. Writing with a quill pen in itself is a very tedious work compared to current-day computer typing. Then comes the need to read and edit and correct. These are all huge labours. A few other people are necessary to do all this.

In addition to all this, William Logan was the District Collector in a district which was incessantly disturbed by communal confrontations between the Hindus and their subordinated populations on one side and Mappillas on the other.

Beyond all this, proper roadways, means of communications, waterway and boating services, administrative set-ups, policing, education, healthcare, drinking water facilities, sanitation, railways, postal services, written codes of laws and judiciary and much else were being set up for the first time in the known history of the location and population. It is only natural to bear in mind that Logan’s mind and time would be required to go into all this also.

So, from all this also it can be presumed that William Logan is not the only person who has written into the text which purports to be his writings. There is very ample indication that even the ‘PREFACE TO VOLUME I’ which purports to be his personal writing was actually some other person’s words. This ‘some other person’ is very clearly a native of the subcontinent.

But then, this action of someone else writing a Foreword or Preface is a common occurrence in the world of book publishing. However, what makes this issue mentionable here is that even in this specific Preface, the same sinister insertion of the vested-interest ideas of a particular section of the population has entered as a sort of an eerie apparition. Actually this ghostly apparition is a ubiquitous presence in almost the entirety of the book, with only one particular section alone being secluded from its presence.

Now, let me mention the words I found on the low-quality content website, to which I had alluded to earlier.

QUOTE: He was conversant in Malayalam, Tamil and Telugu. He is remembered for his 1887 guide to the Malabar District, popularly known as the Malabar Manual. Logan had a special liking for Kerala and its people. END OF QUOTE

It is quite possible that he did know Malayalam, Tamil and Telugu. However, there is no indication in this book that does substantiate this, other than a slight mention of a few Malayalam words. (The location where this is written does not seem to be Logan’s writing). That point does not matter. However, the claim that he was conversant in Malayalam has a major issue. I will take it up later.

The next point is: QUOTE: special liking for Kerala and its people END OF QUOTE

There is nothing in this book that can support a claim of his ‘special liking for the Kerala and its people’. Again, the word ‘Kerala’ has a major issue.

In fact, both the words ‘Malayalam’ and ‘Kerala’ are also part of the sinister doctoring I had mentioned earlier.

My interest is basically connected to my interest in the English colonial rule in the South Asian Subcontinent and elsewhere. I would quite categorically mention that it is ‘English colonialism’ and not British Colonialism (which has a slight connection to Irish, Gaelic and Welsh (Celtic language) populations).

Even though I am not sure about this, I think the book Malabar was made as part of the Madras Presidency government’s endeavour to create a district manual for each of the districts of Madras Presidency. William Logan was a District Collector of the Malabar district of Madras Presidency. The time period of his work in the district is given in this book as:

6th June 1875 to 20th March 1876 (around 9 months) as Ag. Collector. From 9th May 1878 to 21st April 1879 (around 11 months) as Collector. From 23rd November 1880 to 3rd February 1881 (around 2 months) as Collector. Then from 23rd January 1883 to 17th April 1883 (around 3 months) as Collector. After all this, he is again posted as the Collector from 22nd November 1884.

In this book, the termination date of his appointment is not given. Moreover, I have no idea as to why he had a number of breaks within his tenure as the district Collector of Malabar district.

Since this book is seen as published on the 7th of January 1887, it can safely be assumed that he was working on this book during his last appointment as Collector on the 22nd of November 1884.

From this book no personal information about William Logan, Esq. can be found out or arrived at.

It is seen mentioned in a low-quality content website that he is a ‘Scottish officer’ working for the British government. Even though this categorisation of him as being different from British subjects / citizens has its own deficiencies, there are some positive points that can be attached to it also.

He has claimed the authorship of this book. There are locations where other persons are attributed as the authors of those specific locations. Also, there is this statement: QUOTE: The foot-notes to Mr. Græmo’s text are by an experienced Native Revenue Officer, Mr. P. Karunakara Menon. END OF QUOTE.

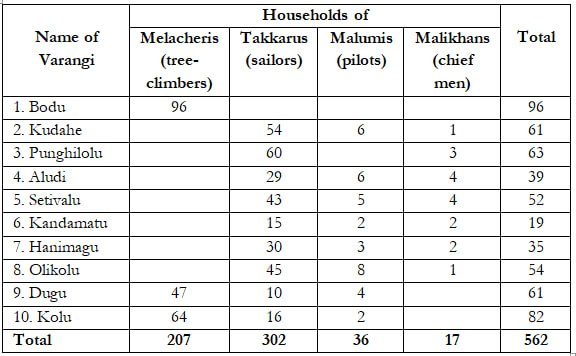

The tidy fact is that the whole book has been tampered with or doctored by many others who were the natives of this subcontinent. Their mood and mental inclinations are found in various locations of the book. The only exception might be the location where Logan himself has dealt with the history writing. More or less connected to the part where the written records from the English Factory at Tellicherry are dealt with.

His claim, asserted or hinted at, of being the author of the text wherein he is mentioned as the author is in many parts possibly a lie. In that sense, his being a ‘Scottish officer’, and not an ‘English officer’ might have some value.

The book Malabar ostensibly written by William Logan does not seem to have been written by him. It is true that there is a very specific location where it is evident that it is Logan who has written the text. However, in the vast locations of the textual matter, there are locations where it can be felt that he is not the author at all.

There are many other issues with this book. I will come to them presently. Let me first take up my own background with regard to this kind of books and scholarly writings.

I need to mention very categorically that I am not a historian or any other kind of person with any sort of academic scholarship or profundity. My own interest in this theme is basically connected to my interest in the English colonial administration and the various incidences connected to it.

I have made a similar kind of work with regard to a few other famous books. I am giving the list of them here:

1. Travancore State Nanual by V Nagam Aiya

2. Native Life in Travancore by Rev. Samuel Nateer F.L.S

3. Castes & Tribes of Southern India Vol 1 by Edgar Thurston

4. Omens and superstitions of southern India by Edgar Thurston

5. The Native races of South Africa by George W. Stow, F.G.S., F.R.G.S.

6. Oscar Wilde and Myself by Alfred Bruce Douglas

7. Mein Mampf by Adolf Hitler – a demystification!

Of the above books, the first six I have recreated into much readable digital books. After that I added a commentary on the contents of each book.

For the fifth book, I have only written a commentary. No attempt was made to recreate it into a more readable digital book. For, the book is available elsewhere in many formats in very highly readable forms. Both digital as well as print version.

Why I have mentioned this much about the way I work on these books is to convey the idea that when I work on a book to create a readable digital version, I get to read the text, invariably.

In the case of this book, Malabar, I have gone through each line and paragraph. It is possible that I have missed a lot of errors in my edited version. For, I did not get ample time to proofread. For, taking out the text from very faint, scanned versions of the original book was a very time-taking work. The work was tedious. And apart from that, getting to reformat the text is an extremely slow-paced work.

But the word-by-word working on the text gave me the opportunity to go through the text in a manner which no casual reader might do. I could enter in almost every nook and corner of the textual matter. And many minor, and yet significant information have come into my notice.

Since I have done a similar work on Travancore State Manual by V Nagam Aiya and on Native Life in Travancore by Rev. Samuel Mateer, I have had the opportunity to understand the contemporary happenings of those times in the next door native-king ruled kingdom of Travancore.

Apart from all that, I do personally have a lot of information on this landscape and how it experienced and reacted to the English rule. It goes without saying that the current-day formal history assertions about the English colonial rule are totally misleading and more or less absolute lies. Even the geographical frame on which this history has been built upon is wrong and erroneous.

I have been hearing the words to the effect: Logan said this or that in his Malabar Manual, on many things concerning the history and culture of Malabar. However, it was only in this year, that is, 2017, that I got a full page copy of his Two volume book.

Even though this book is named Malabar, it is generally known as the Malabar Manual in common parlance. I think this is due to the fact that this book must have been a part of the District Manuals of Madras (circa 1880), which were written about the various districts, which were part of the Madras Presidency of the English-rule period in the Subcontinent. In fact, this is the understanding one gets from reading a reference to this book in Travancore State Manual written by V Nagam Aiya. In fact, Nagam Aiya says thus about his own book: ‘I was appointed to it with the simple instruction that the book was to be after the model of the District Manuals of Madras’.

I initiated my work on this book without having any idea as to what it contained, other than a general idea that it was a book about the Malabar district of Madras Presidency.

However, as I progressed with the work and the reading, a very ferocious feeling entered into me that this is a very contrived and doctored version of events and social realities. In the various sections of the book, wherein there is no written indication that it is not written by Logan, I have very clearly found inclinations and directions of leanings shifting. In certain areas, they are totally opposite to what had been the direction of leaning in a previous writing area.

It is very easily understood that words do have direction codes not only in their code area, but also in the real world location. A slight change of adjective can shift the direction of loyalty, fidelity and fealty from one entity to another. A hue of a hint or suggestion can shift this direction. With a single word or adjective or usage, placed in an appropriate location with meticulous precision, an individual’s bearing and aspirations can be differently defined. An explanation for an action can shift from portraying it as grand to framing it as a gratuitous deed.

Only a very minor part of this book could be the exact textual input of William Logan. Other parts of the book which are not mentioned as of others can actually be the writings of a few others.

This book has been written for the English administrators. From that perspective, there would be no attempt on the part of William Logan to fool or deceive the English administrators, with regard to the realities of the inputs of English administration. This is the only location in this book, where everything is honest.

In all the other parts, half-truths, partial truths, partial lies, total lies and total suppression of information are very rampant. Moreover, there might even be total misrepresentation of events and populations. The natives of the subcontinent who have very obviously participated in the creation of this book have made use of the opportunity presented to them to insert their own native-land mutual jealousies, repulsions, antipathies etc. in a most subtle manner. This very understated and very fine and slender manner of inserting errors into the textual content has been resorted to, just to be in sync with the general gentleness of all English colonial stances.

That was the first attempt at doctoring the contents of this book.

There was again a second attempt at doctoring the contents of this book. That was in 1951. On reading the text itself I had a terrific feeling that some terrible manipulation and doctoring had been accomplished on this book much after it had been first published in 1887. For, this book was actually an official publication of the British colonial administration in the Madras Presidency. However, the flavour of a British / English colonial book was not there in the digital copy of the book which I had in my hands. This copy had been a re-edited and reprinted work, published in 1951.

Some very fine aura of an English colonial book was seen to have been wiped out. Even though it could be quite intriguing as to why an original book had to be edited and various minor but quite critical changes had been inserted into this book, there are very many reason that why such malicious actions have been done. In fact, after the formation of three nations inside the South Asian Subcontinent, there have been many kinds of manipulations on the recorded history of the location. This has been done to suit the policy aims of the low-class nations that have sprung up in the region.

On checking the beginning part of the book, I found this writing:

QUOTE: In the year 1948, in view of the importance of the book, the Government ordered that it should be reprinted. The work of reprinting was however delayed, to some extent, owing to the pressure of work in the Government Press. While reprinting the spelling of the place names have, in some cases, been modernized.

Egmore, B. S. BALIGA,

17th September 1951 Curator, Madras Record Office

END OF QUOTE

So, that much admission from a government employee is there.

A few decades back, I was staying in a metropolitan city of India. This city had been the headquarters of one of the Presidencies of British-India. I need to explain what a Presidency is. For there might be readers who do not understand this word.

The English colonial rule in the South Asian Subcontinent actually was centred on three major cities. Bombay, Madras and Calcutta. Even though the colonial rule is generally known as British-rule and the location as British-India, there are certain basic truths to be understood. The so-called British-rule was more or less an English-rule, centred on a rule by England. It was not a Celtic language or Celtic population rule.

William Logan, who purports to be the author of this book, is not an Englishman. So to that extent, he is removed from the actual fabulous content of the English-rule in the subcontinent.

The second point to mention is that even though there is a general misunderstanding that the whole of the subcontinent was part of British-India and British-Indian administration, the rough truth is that most of the locations outside the afore-mentioned three Presidencies were not part of British-India or British-Indian administration.

However, due to the extremely fabulous content quality of the British-Indian administration, as well as the quaint refined quality, dignified way of behaviour, honourableness, sense of commitment and dependability of the English administration, all the other native-kingdoms which existed in the near proximity of the Presidencies inside the subcontinent, more or less adhered intimately to British-India without any qualms. For, there are no self-depreciating verbal usages of servitude in English. In the native feudal-languages of the location, such a connection would have affected their stature very adversely in the verbal codes. [Please read the chapter on Feudal Languages in this Commentary)

In the local culture, the exact traditional history is that of backstabbing, treachery, usurping of power, going back on word, double-crossing &c. When a very powerful political entity appeared on the scene, which was seen quite bereft of all these sinister qualities, everyone understood that it was best to connect to this entity.

However, this was to lead these kingdoms to their disaster and doom later on. For, a general feeling spread that all these kingdoms were part of British-India. Even in England this was the general feeling. An extremely disparaging usages such as ‘Princely state’ and ‘Indian Prince’ came to be used in English language to define them, due to this misunderstanding.

Actually the independent kingdoms were not ‘Princely states’. Nor were their kings mere ‘Indian princes’. They were kings. For instance, Travancore was not a Princely State. It was an independent kingdom. It was true that it was in alliance with British-India. To use this term ‘alliance’ to mention Travancore as bereft of its own sovereignty, is utter nonsense.

For, it is like saying that Kuwait is part of USA just because it is under the US protection. Or Japan, and many other similar low-class nations, which have made use of a close contact with the US to bolster up their own nations.

Travancore did mention its own stature as an independent kingdom very forcefully in a legal dispute with the Madras government.

Dewan Madava Row wrote thus to the government of the Madras Presidency in 1867: QUOTE:

(1 The jurisdiction in question is an inherent right of sovereignty

(2 The Travancore State being one ruled by its own Ruler possesses that right

(3 It has not been shown on behalf of the British Government that the Travancore State ever ceded this right because it was never ceded, and

END OF QUOTE

However, for the independent kingdoms in the subcontinent, this close connection with British-India later turned out to be a suicidal stranglehold. For, in the immediate aftermath of World War 2, a total madman and insane criminal became the Prime Minister of Britain. In his totally reckless administration that lasted around five years, he tumbled down the English Empire, all over the world.

In the South Asian subcontinent, the British-Indian army was divided into two and handed over to two politicians who had very good connection to the British Labour Party leaders.

These two leaders used the might of the British-Indian army which had come into their own hands to more or less run roughshod over all the native-kingdoms of the subcontinent. They were all forcefully added to the two newly-created nations, Pakistan and India. This action might need to be discussed from a very variety of perspectives. However, this book does not aim to go into that detail.

However, the dismantling of the English-rule was disastrous to the people. In the northern parts of the subcontinent, which is mainly the Hindi hinterland, a communal confrontation took place between the Muslims and the non-Muslim populations. Around 10 lakh (1 million) people were slaughtered. Burned, and hacked. Towns and villages which had lived in total peace and prosperity under the English-rule became battlegrounds. No house or household was safe. People had the heartbreaking experience of seeing their youngsters broken down physically.

This was how the two nations of Pakistan and India were founded. Compared to the other parts of the subcontinent, the average social-quality of Hindi-speakers is low. This itself is a very fabulous illustrative point. For, on seeing Hindi films one might get a feeling that the Hindi-speakers are of a very resounding quality. Even native-English nations are being befooled by the Bombay (Hindi) film world, with the cunning use of fabulous Hindi films.

However, the truth remains that all over the subcontinent, including Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, the lower-placed sections of the feudal-language speaking sections of the populations do suffer from a mental and social suppression that cannot be seen or understood in English.

Now coming back to the madman who dismantled the English-Empire in the subcontinent and elsewhere, I personally do not know what retribution he received from providence. However, for the terrible suffering he let loose all around the world in general and in the South Asian Subcontinent in particular, he deserves to rot in hell till eternity. Not only him, but all those who support his evil deed also deserve just retribution from Nemesis.

Let me go back to the point I left. I was staying in a Metropolitan city in India which had been a headquarters city of one British-Indian Presidency, a few decades back. I was quite young. I had a casual conversation with an old man who had been a contemporary of the English-rule period in the city.

I asked him about the general quality of the Englishmen who had been officers in the administration. He said, they were all quite nice. But then, they were cut-off from the people. They had around them a coterie of natives of the subcontinent. These persons were generally the Hindus (Brahmins &c.) and other higher castes. There were lower castes also. However, all of them kept the native-English officers inside a social corridor which they controlled. They acted quite nice and coy to the native-English officers. But actually they were very cunning, and self-centred and had very obvious selfish interests.

This much this man told me. However, the vast amplitude of the information is like this:

The gullible native-English officers acted as per the advice of this cunning coterie. These cunning local vested-interest groups literally fed the native-English officials with their own native-land repulsions, caste hatred, antipathies and religious hatred. And also colluded with the native business interests to influence policy decisions in the sphere of economic and fiscal matters.

Even though, it is true that the native-English officers did in many instances see through their cunning intentions, it is not easy to detach completely from its snares. For, the most powerful weapon of luring and snaring an unwary adversary used in all feudal languages nations, is the weapon of hospitality, and effusive and quite overt friendliness.

In many cases, the native-English officials understood that a native of the subcontinent is at his most dangerous stance, when he acts most friendly and helpful. This is actually a part of the code-work inside feudal languages. I will deal with that later.

Now, why did I mention this idea here?

On reading the ‘Malabar’ written by William Logan, the impression that can spring spontaneously to my mind is of a very gullible native-English administration doing its best and giving its best to a population group which they cannot understand. Actually it is not one population group that they are dealing with. They are actually dealing with a series of population groups, each one them having its own aims and ambitions, which are totally different and antagonistic to various other groups. Even though the native-English go on insisting and try to define the native populations as belonging to one nation, there is no such an idea of a Nation-state in the minds of the populace.

In fact, the very idea of a nation-state is a mad insertion by the native-English.

William Logan was authorised to write this book. He had at his command a lot of native-officials up to the level of the Deputy District Collector to help him. He allowed them to write many notes and articles, which even though he must have edited, have all messed-up the quality of the information.

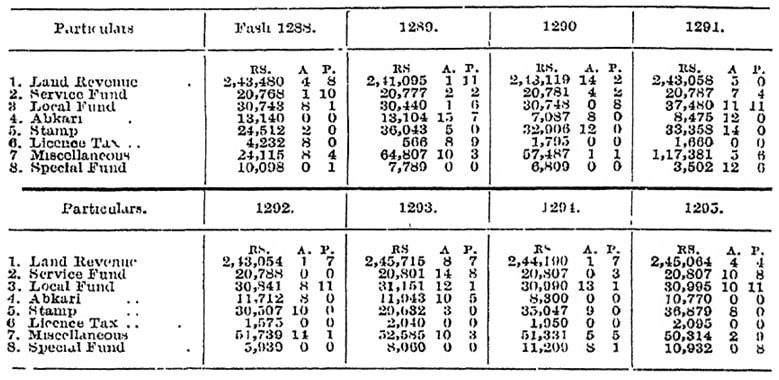

Logan has the feel of having been taken for a ride. But then, it can be understood that a lot of persons have worked on this book. For, there are a lot of tables and lists. All these can be understood to have been done by other persons. The book is quite huge. It has more than five hundred thousand words (more than 5 lakh words).

It contains a number of footnotes. Many of these foot-notes alludes to or point to or quotes from many ancient or scholarly books. Some of these books are the works of other language writers or travellers.

It is practically impossible for William Logan to have taken up these various books for reading and referring. Travelling in those days was quite a cumbersome action. There were many places where one could go only in a bullock cart.

Beyond all this, this book was written in a manuscript form in those days. There were no computers or any other digital gadgets available. Writing with a quill pen in itself is a very tedious work compared to current-day computer typing. Then comes the need to read and edit and correct. These are all huge labours. A few other people are necessary to do all this.

In addition to all this, William Logan was the District Collector in a district which was incessantly disturbed by communal confrontations between the Hindus and their subordinated populations on one side and Mappillas on the other.

Beyond all this, proper roadways, means of communications, waterway and boating services, administrative set-ups, policing, education, healthcare, drinking water facilities, sanitation, railways, postal services, written codes of laws and judiciary and much else were being set up for the first time in the known history of the location and population. It is only natural to bear in mind that Logan’s mind and time would be required to go into all this also.

So, from all this also it can be presumed that William Logan is not the only person who has written into the text which purports to be his writings. There is very ample indication that even the ‘PREFACE TO VOLUME I’ which purports to be his personal writing was actually some other person’s words. This ‘some other person’ is very clearly a native of the subcontinent.

But then, this action of someone else writing a Foreword or Preface is a common occurrence in the world of book publishing. However, what makes this issue mentionable here is that even in this specific Preface, the same sinister insertion of the vested-interest ideas of a particular section of the population has entered as a sort of an eerie apparition. Actually this ghostly apparition is a ubiquitous presence in almost the entirety of the book, with only one particular section alone being secluded from its presence.

Now, let me mention the words I found on the low-quality content website, to which I had alluded to earlier.

QUOTE: He was conversant in Malayalam, Tamil and Telugu. He is remembered for his 1887 guide to the Malabar District, popularly known as the Malabar Manual. Logan had a special liking for Kerala and its people. END OF QUOTE

It is quite possible that he did know Malayalam, Tamil and Telugu. However, there is no indication in this book that does substantiate this, other than a slight mention of a few Malayalam words. (The location where this is written does not seem to be Logan’s writing). That point does not matter. However, the claim that he was conversant in Malayalam has a major issue. I will take it up later.

The next point is: QUOTE: special liking for Kerala and its people END OF QUOTE

There is nothing in this book that can support a claim of his ‘special liking for the Kerala and its people’. Again, the word ‘Kerala’ has a major issue.

In fact, both the words ‘Malayalam’ and ‘Kerala’ are also part of the sinister doctoring I had mentioned earlier.

Last edited by VED on Mon Jun 16, 2025 5:45 am, edited 10 times in total.

2. The information divide

2 #

There is a huge information divide between native-English speakers and feudal-language speakers. It is possible for feudal-language speakers to understand the very simple social logic of native-English speakers. However, the reverse is not true.

Feudal-language social systems are quite complicated. What is seen on the surface has no connection with reality. Why this is so has to be explained in detail.

Feudal-language social systems are quite complicated. What is seen on the surface has no connection with reality. Why this is so has to be explained in detail.

Last edited by VED on Fri Feb 16, 2024 12:16 pm, edited 3 times in total.

3. The layout of the book

3 #

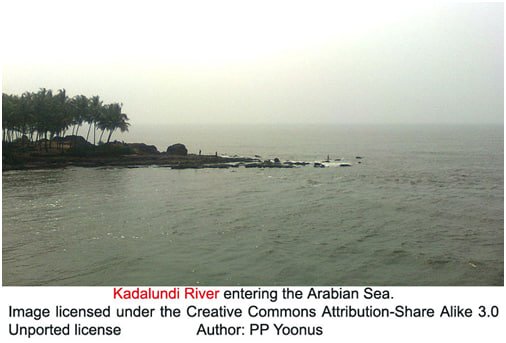

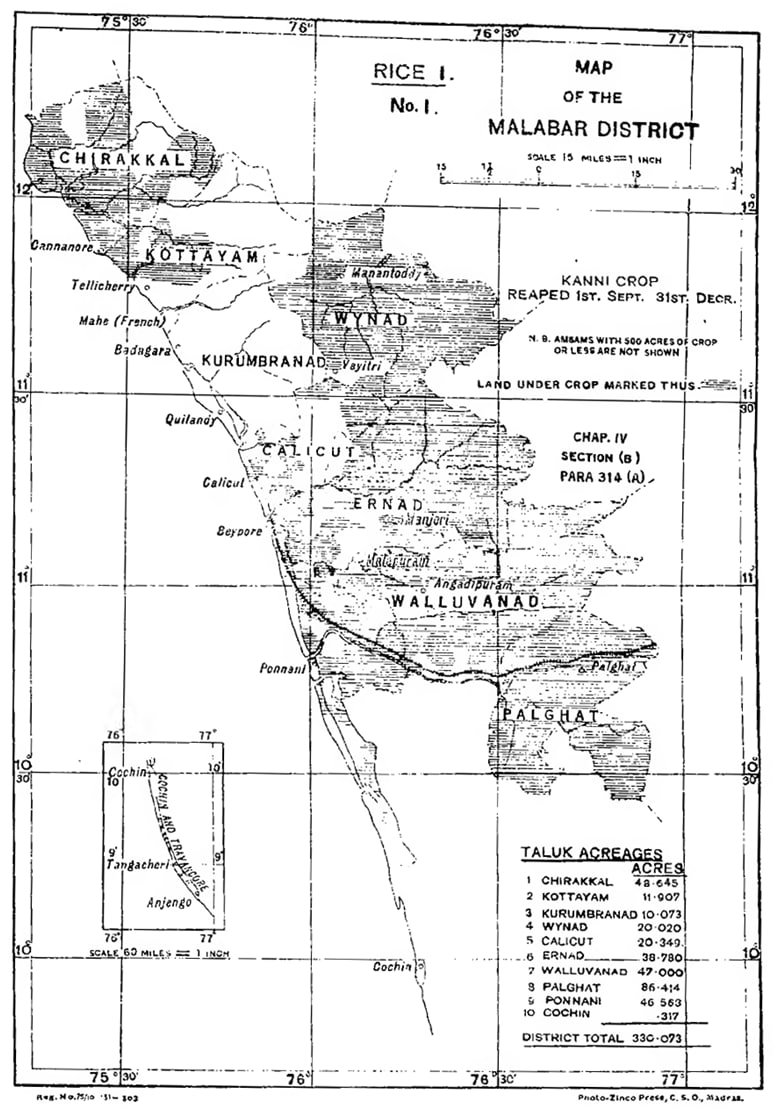

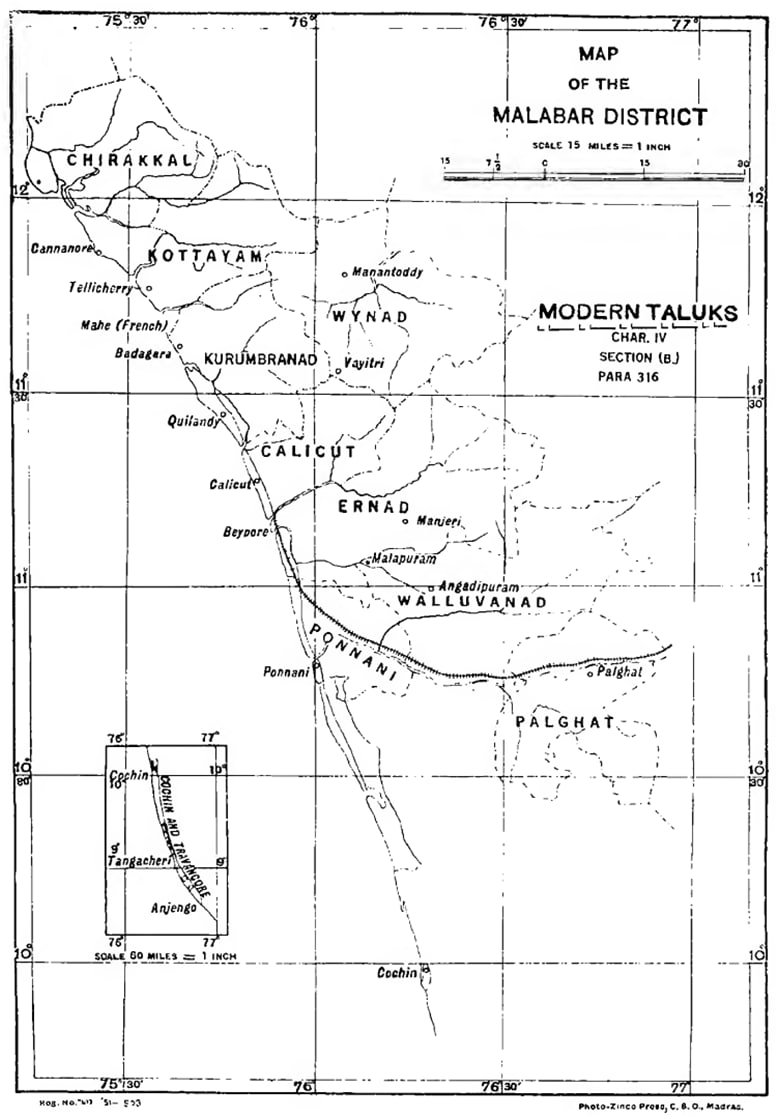

The original book was published in two volumes. Volume One contains the following Chapters: The District, The people, History and This Land.

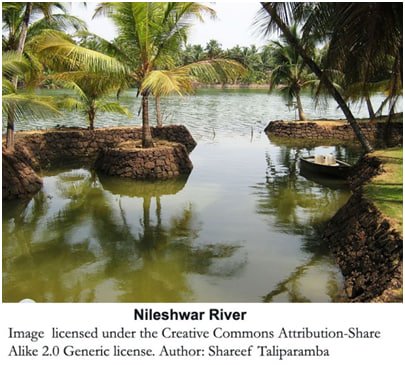

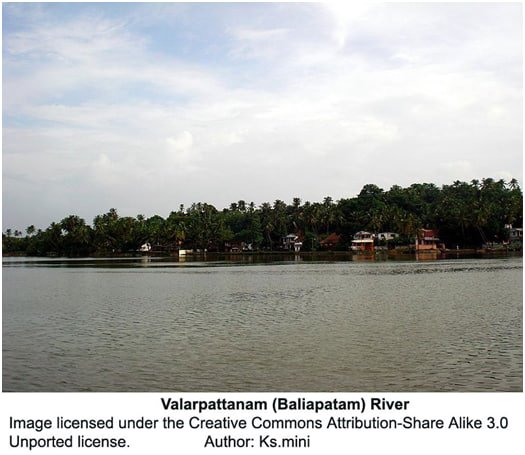

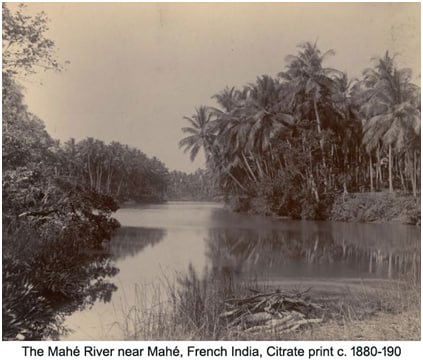

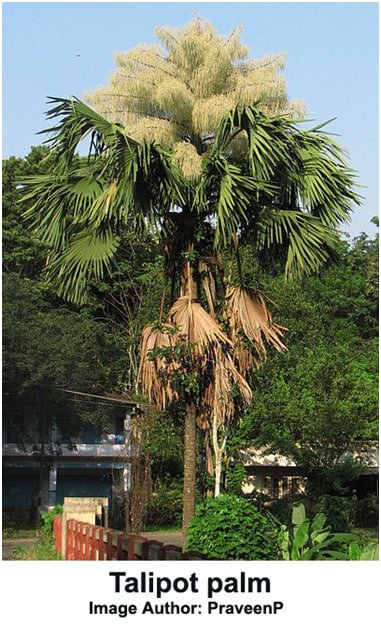

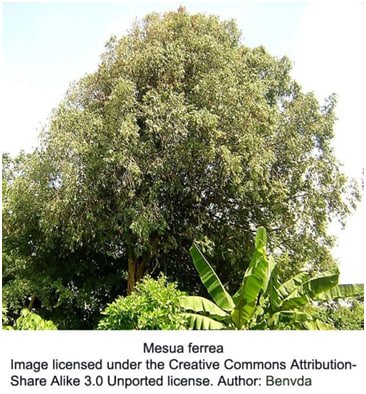

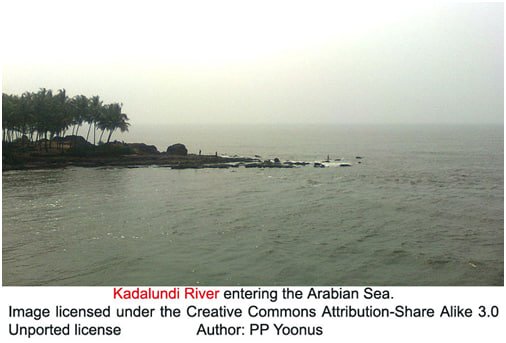

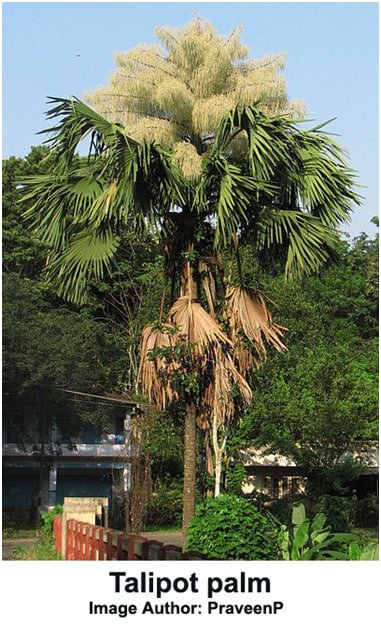

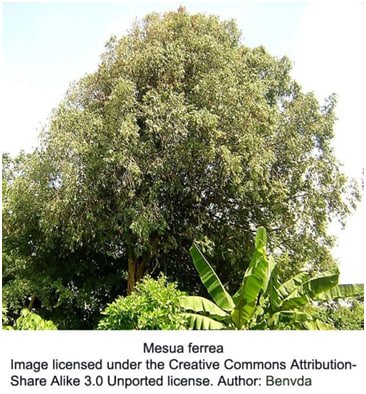

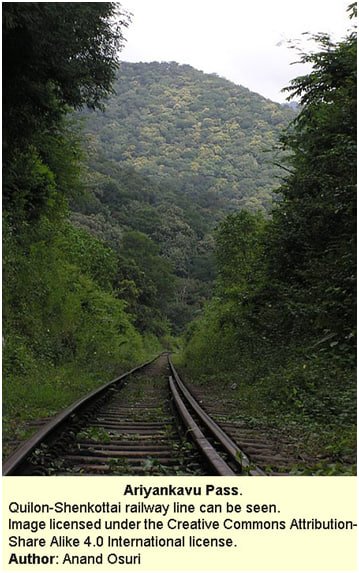

The first chapter, The District deals with the physical features, rivers, mountains, the Fauna and Flora, Road, passes, railway, Port facilities etc. The Fauna and Flora section has been written by Rhodes Morgan, F.Z.S., Member of the British Ornithologists Union, District Forest Officer, Malabar.

The second chapter is about the people, population, villages, towns, habitation, rural organisation, language, literature and state of awareness of the people, caste issue and occupation, manners and customs, religions, famines, diseases and treatment.

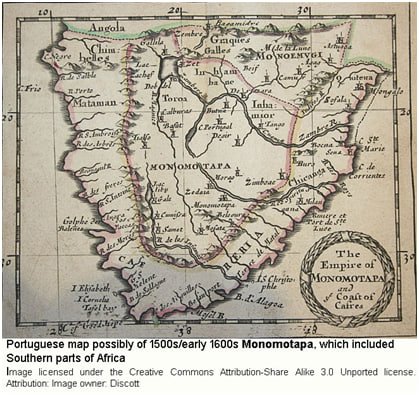

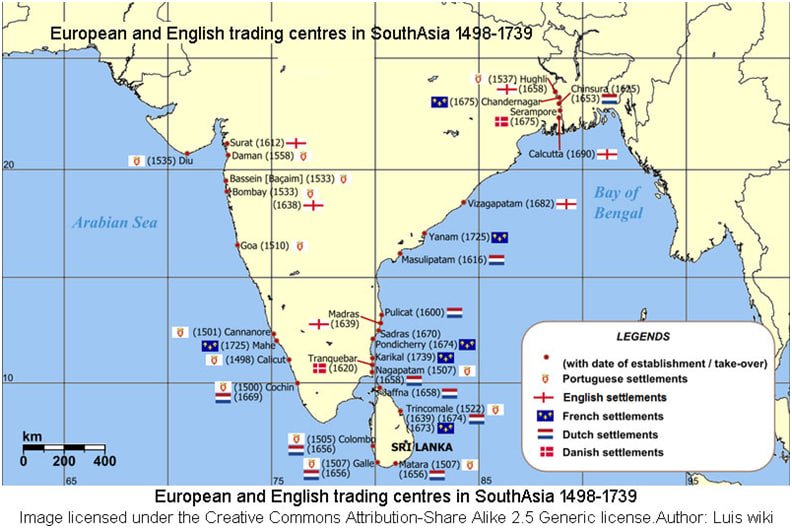

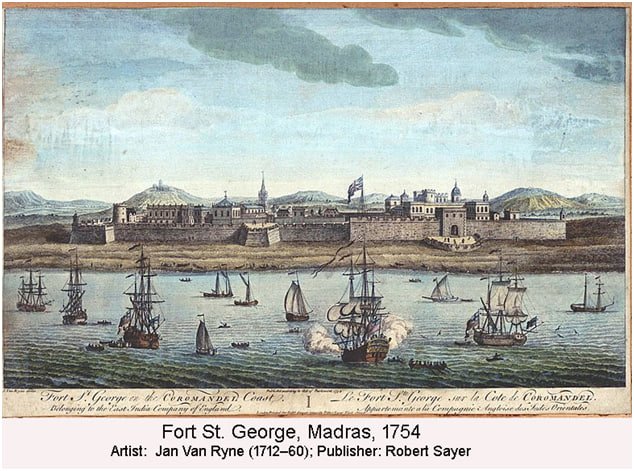

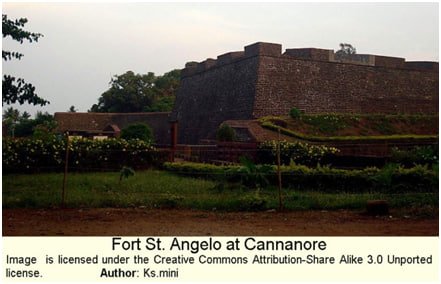

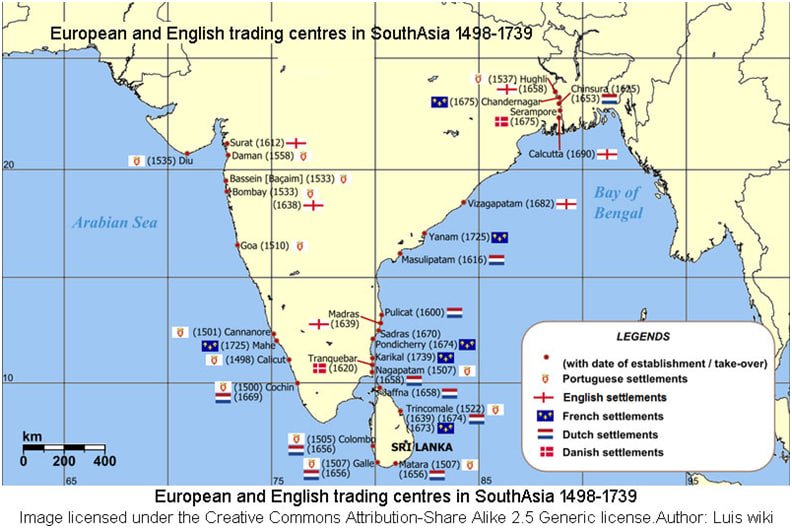

The third chapter is about History of the location. Commencing from the traditions that gives a hint of the antiquity of the place, it moves on to time when Portuguese traders tried to set up a trading centre here. Then came the Dutch and after them the arrival of the English traders.

The fourth chapter is This Land. In this location, the attempts to understand the land tenures and land revenue systems are seen. The focus is on the English Factory at Tellicherry. The writing moves through the various minor historical incidences that slowly lead to the establishment of an English administrative system in Malabar.

With the exception of the Flora and Fauna section, I think that whole book has ostensibly been written by William Logan. That is the impression that comes out.

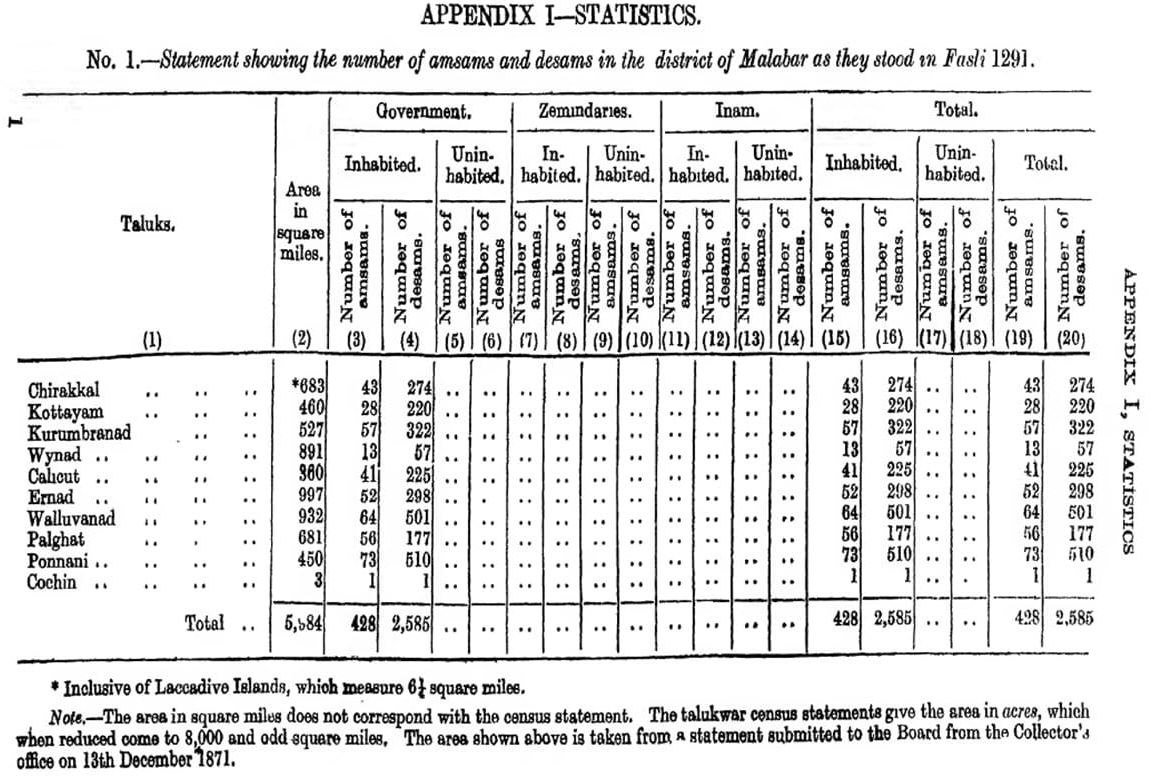

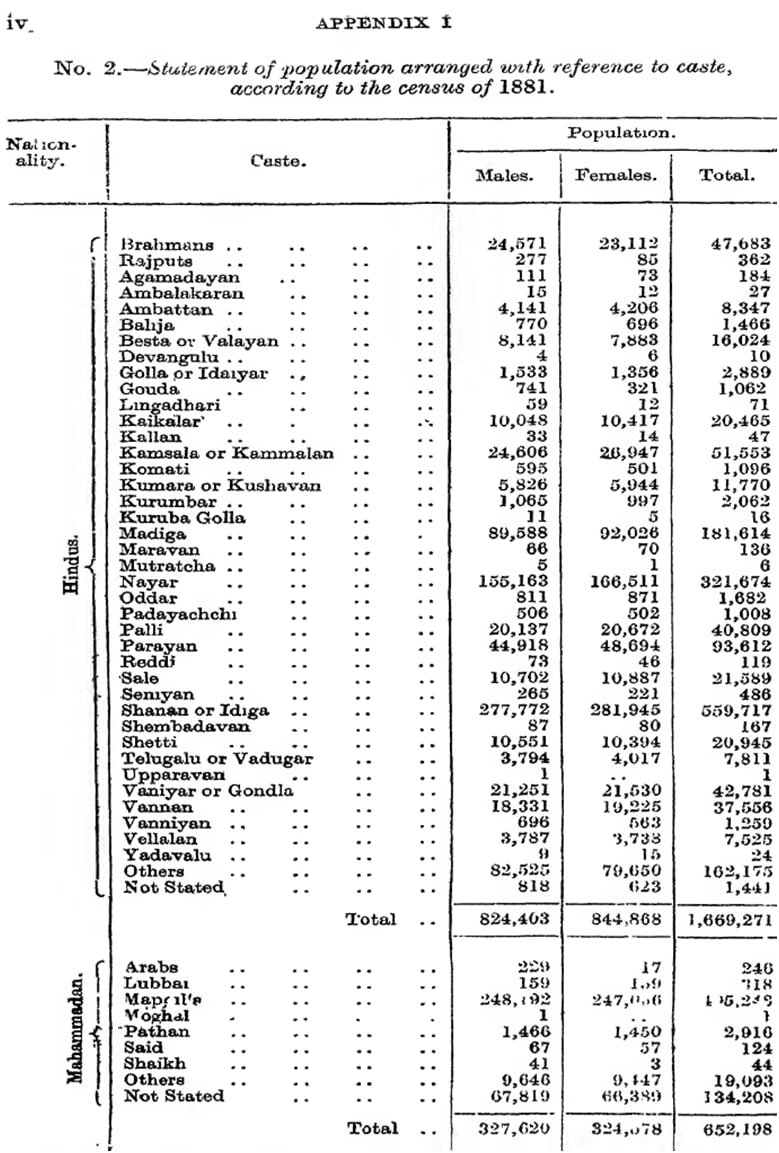

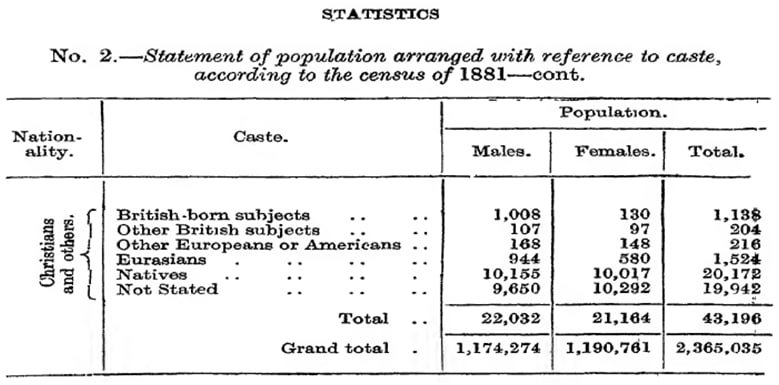

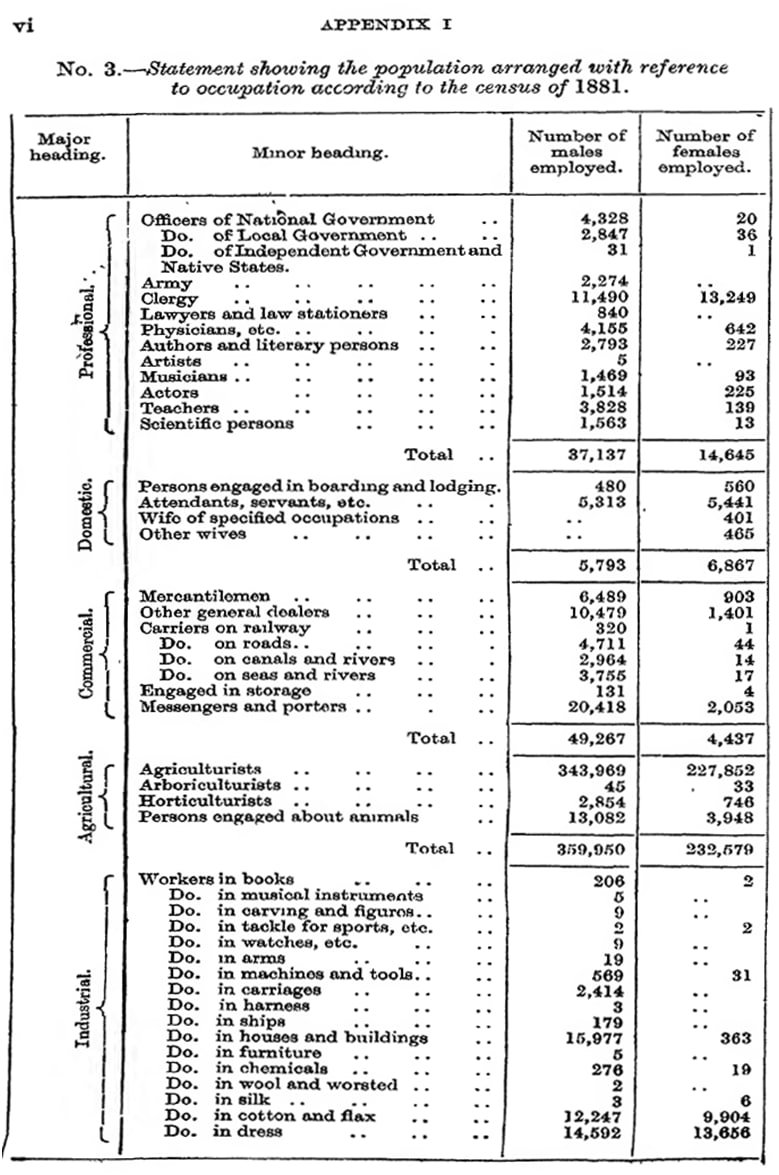

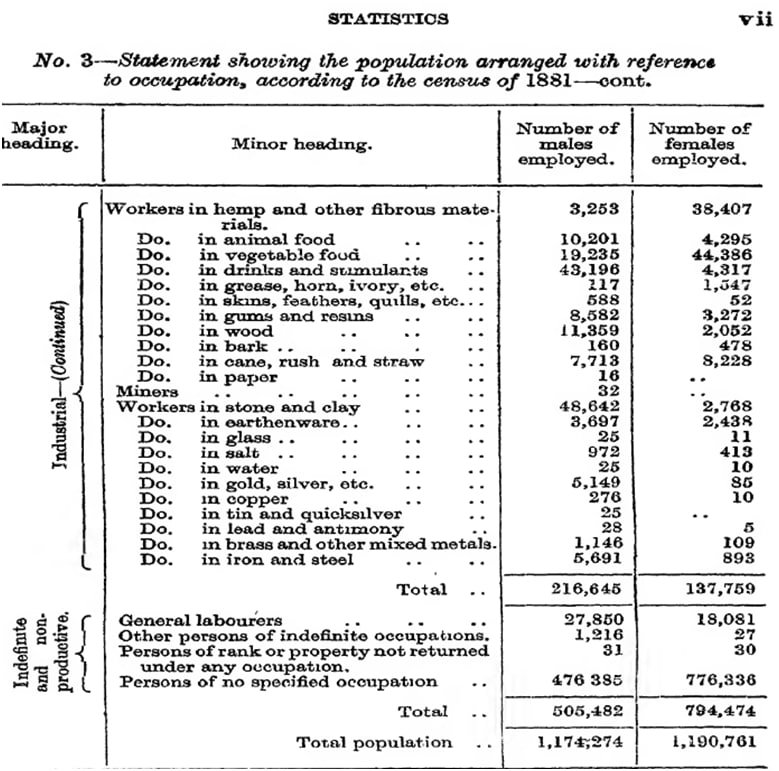

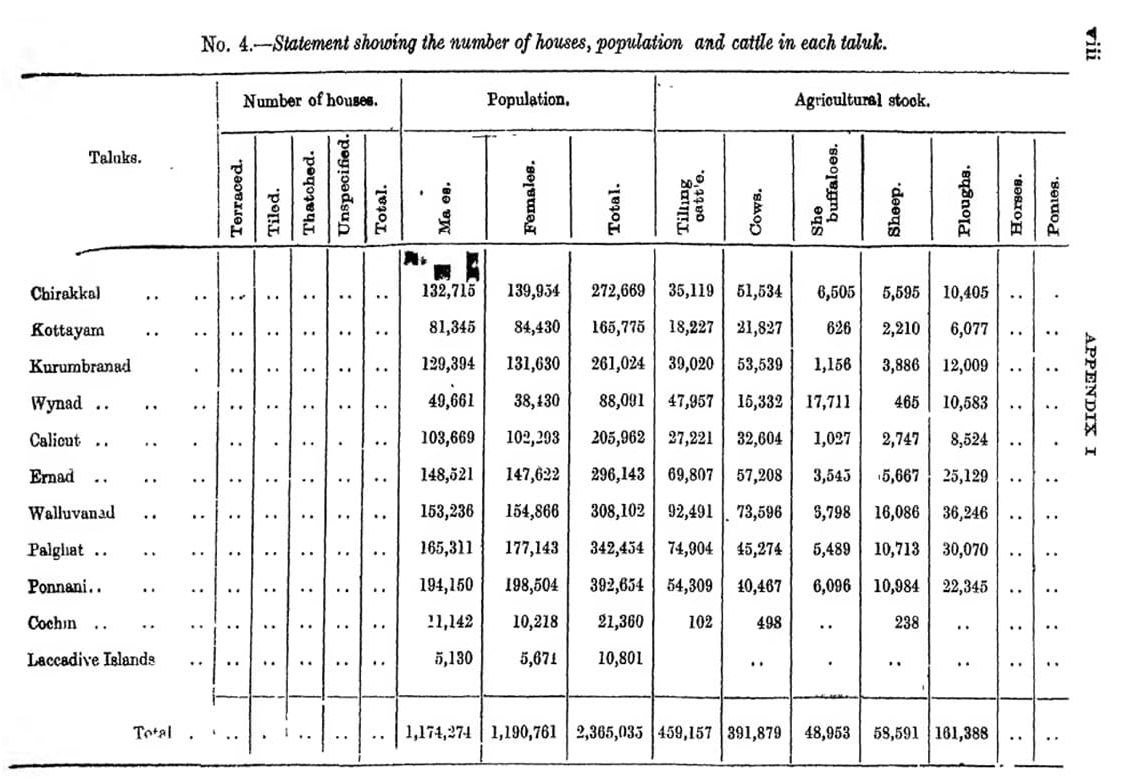

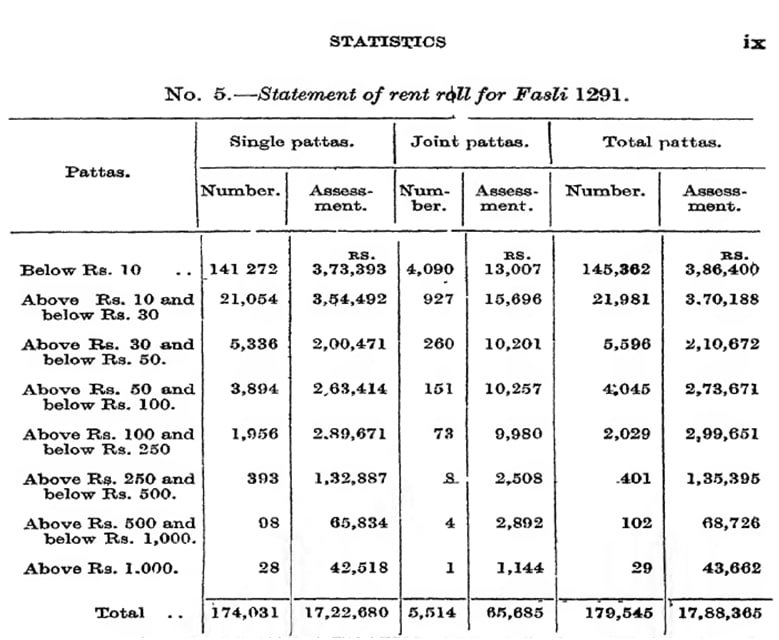

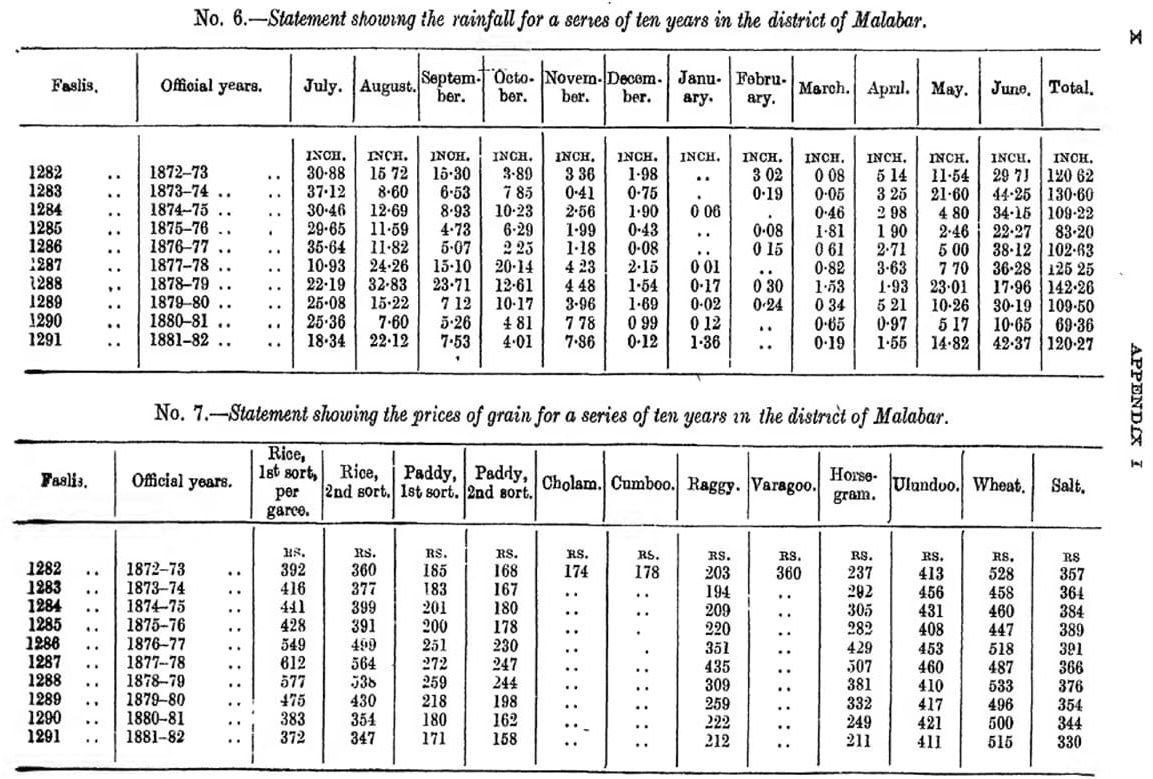

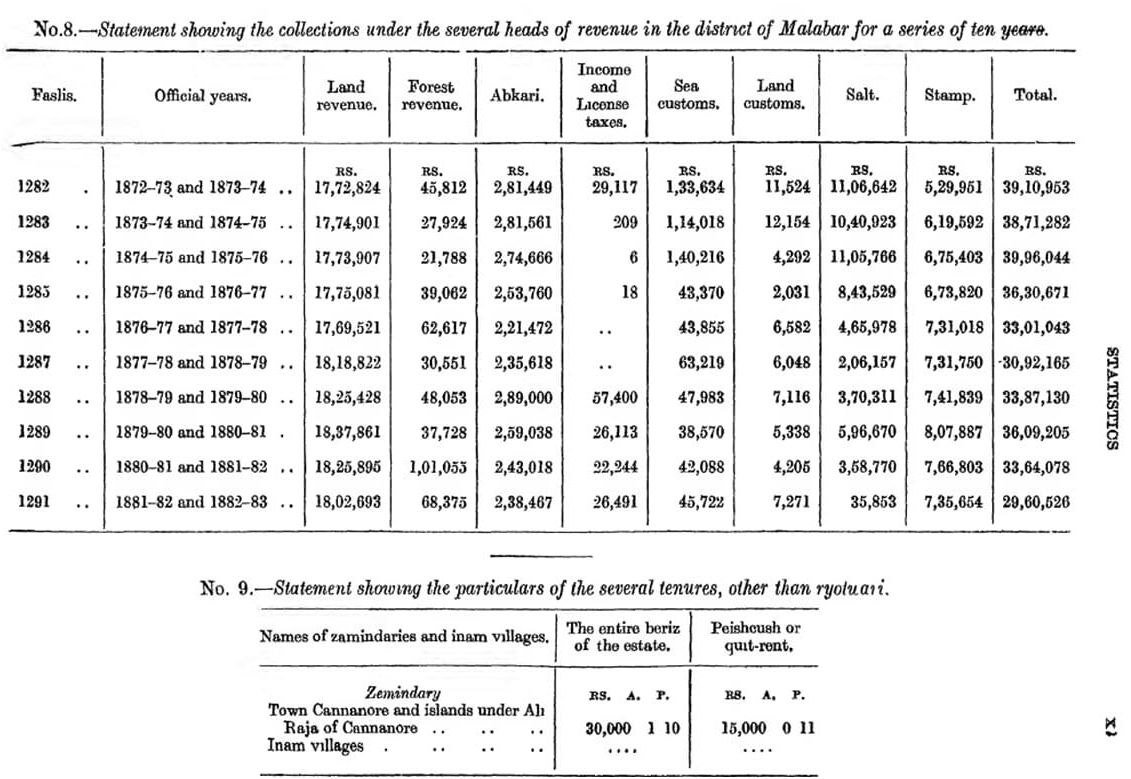

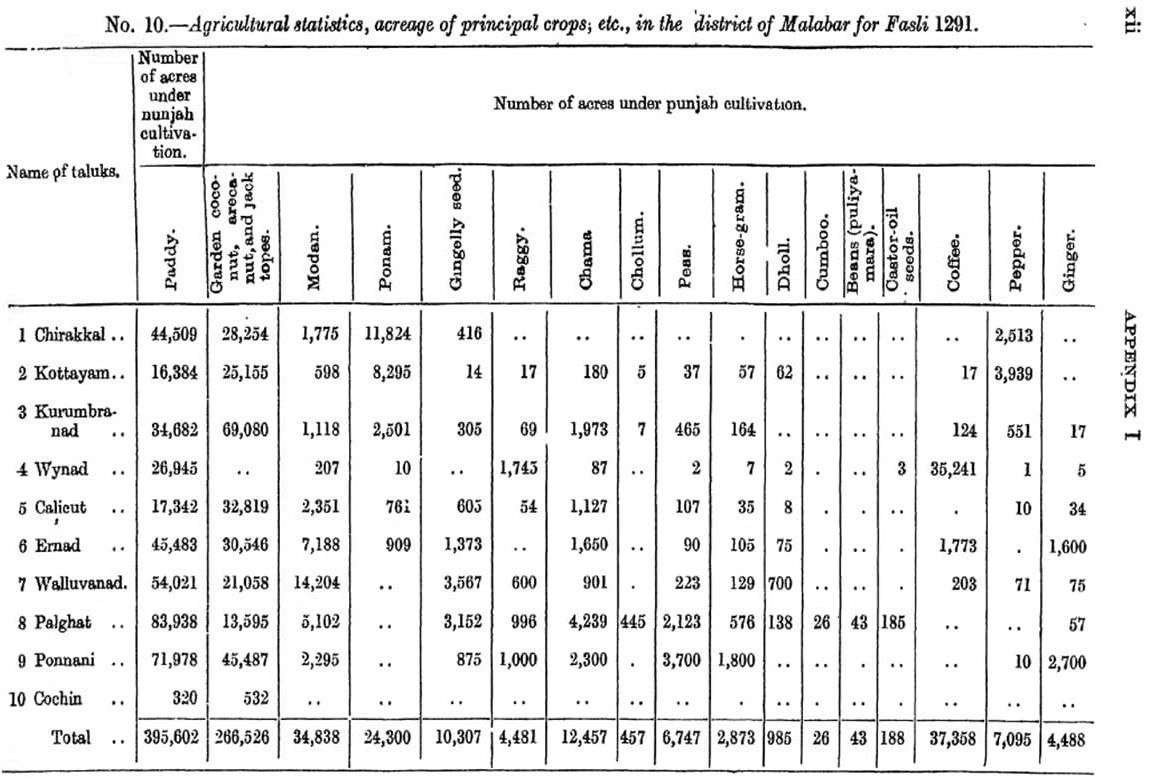

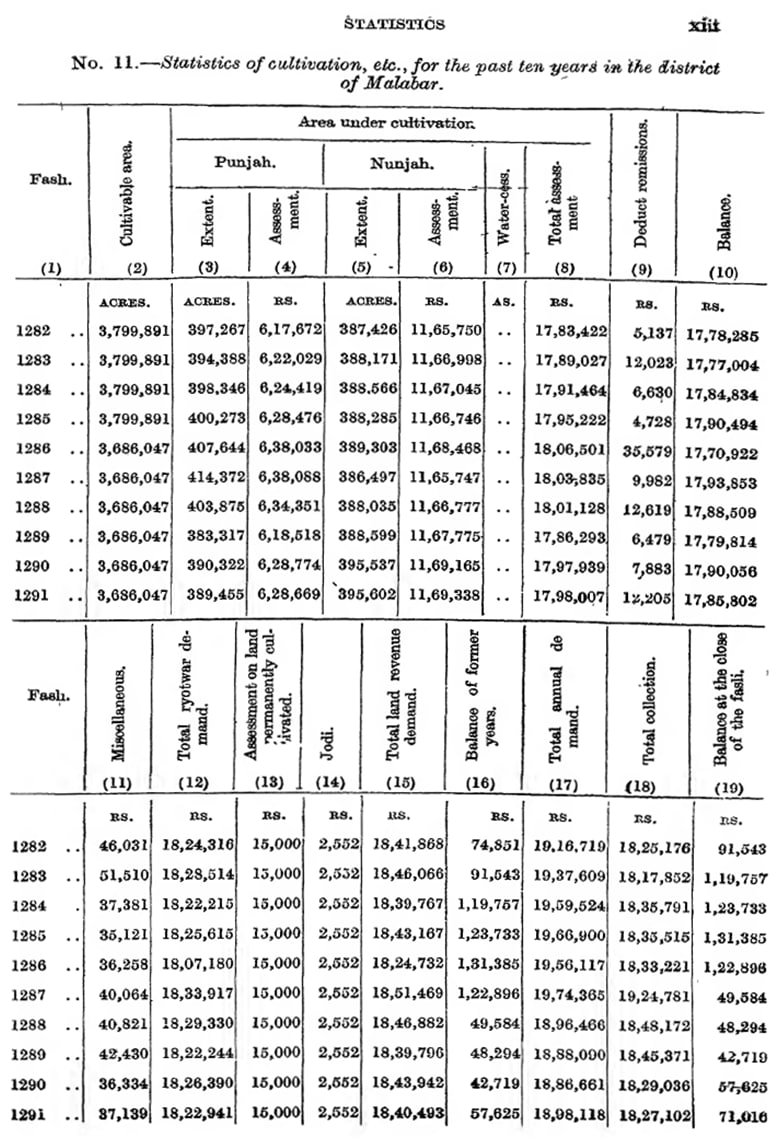

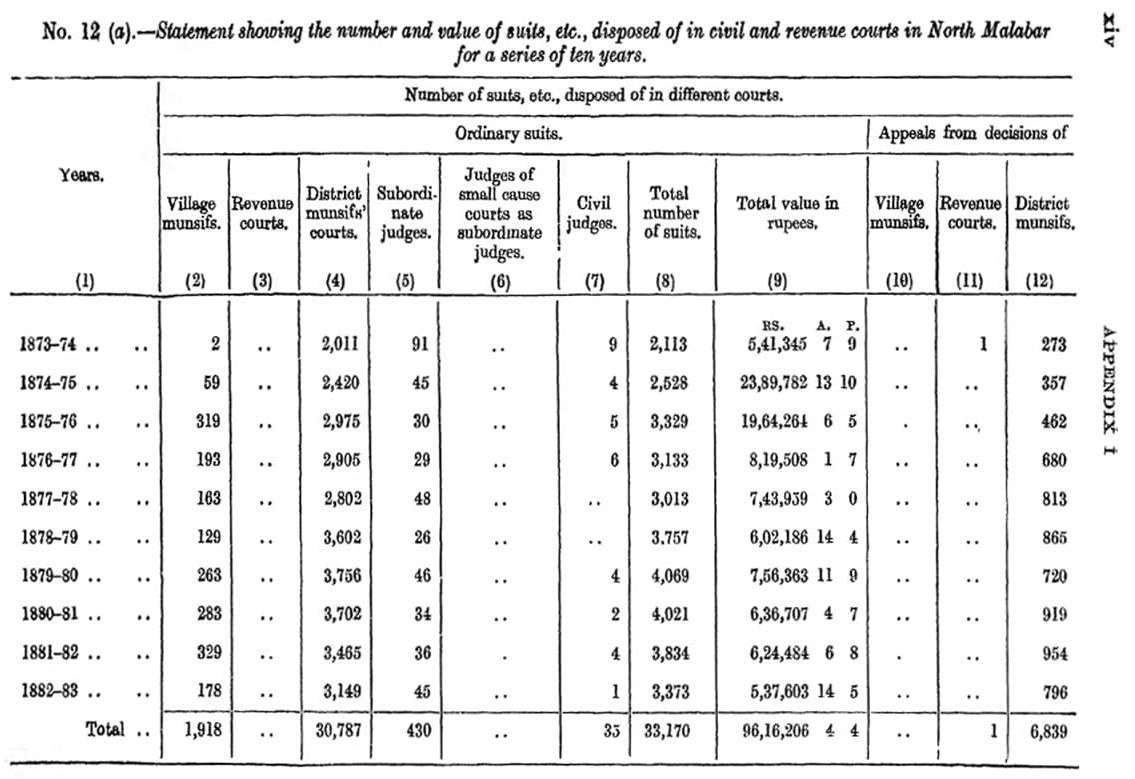

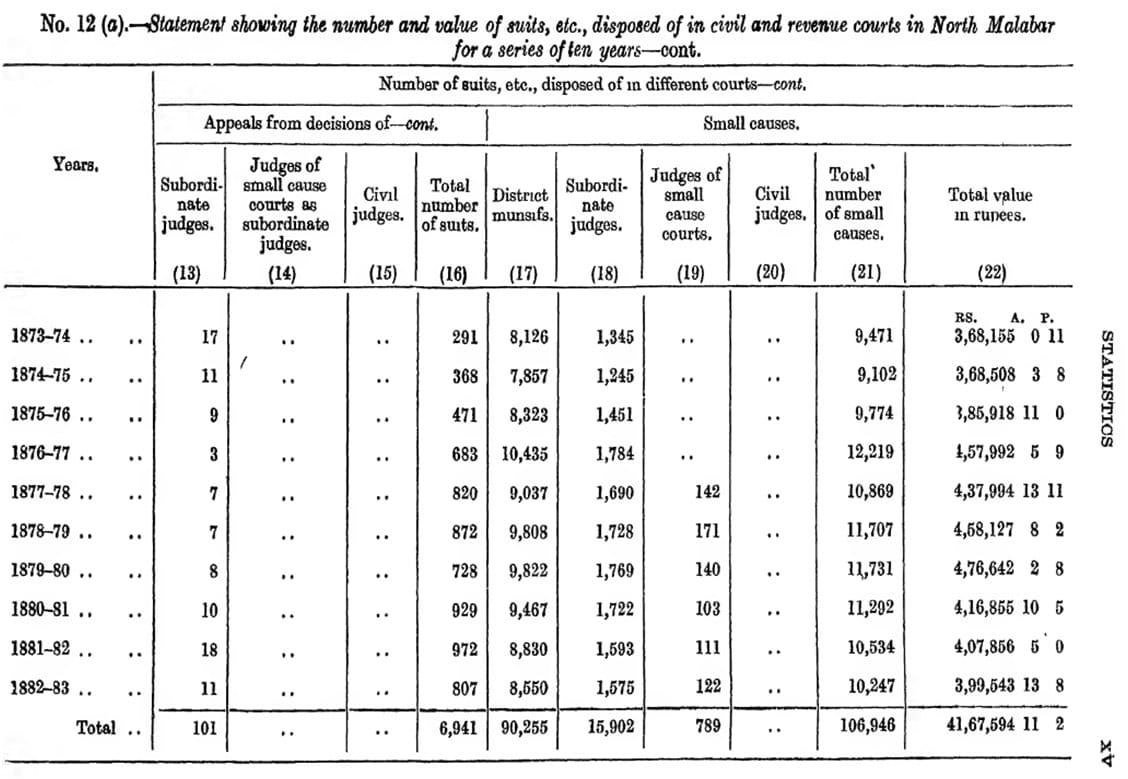

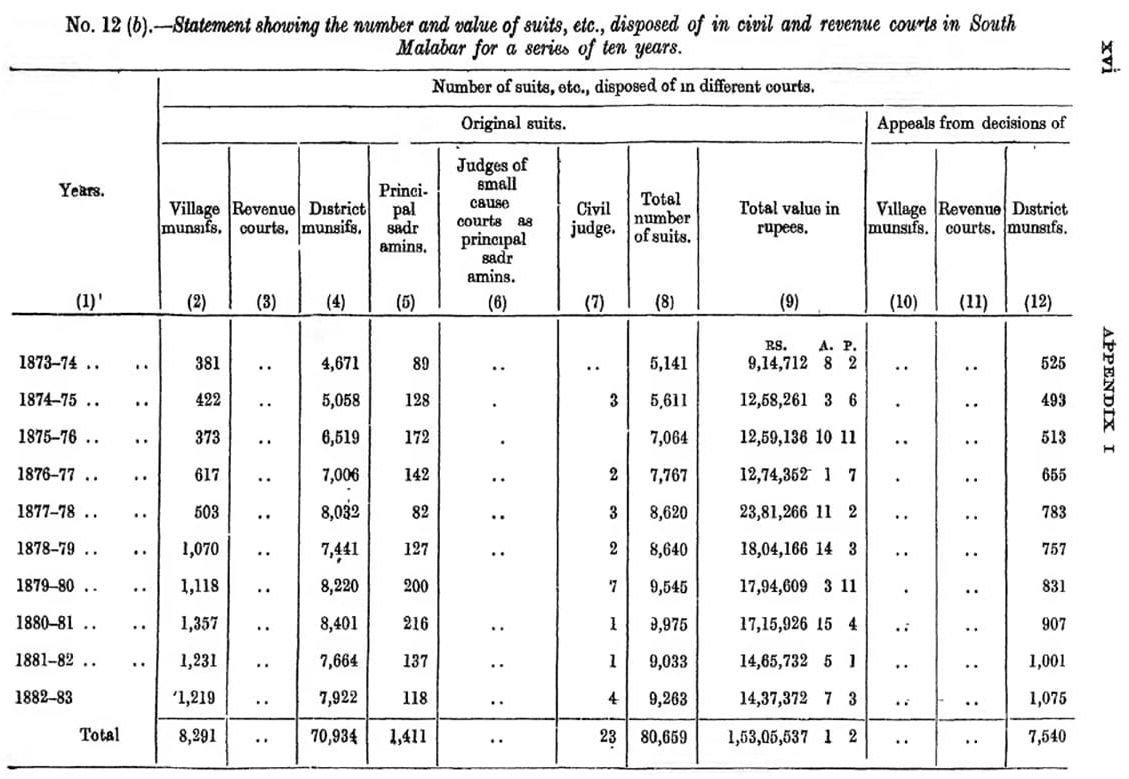

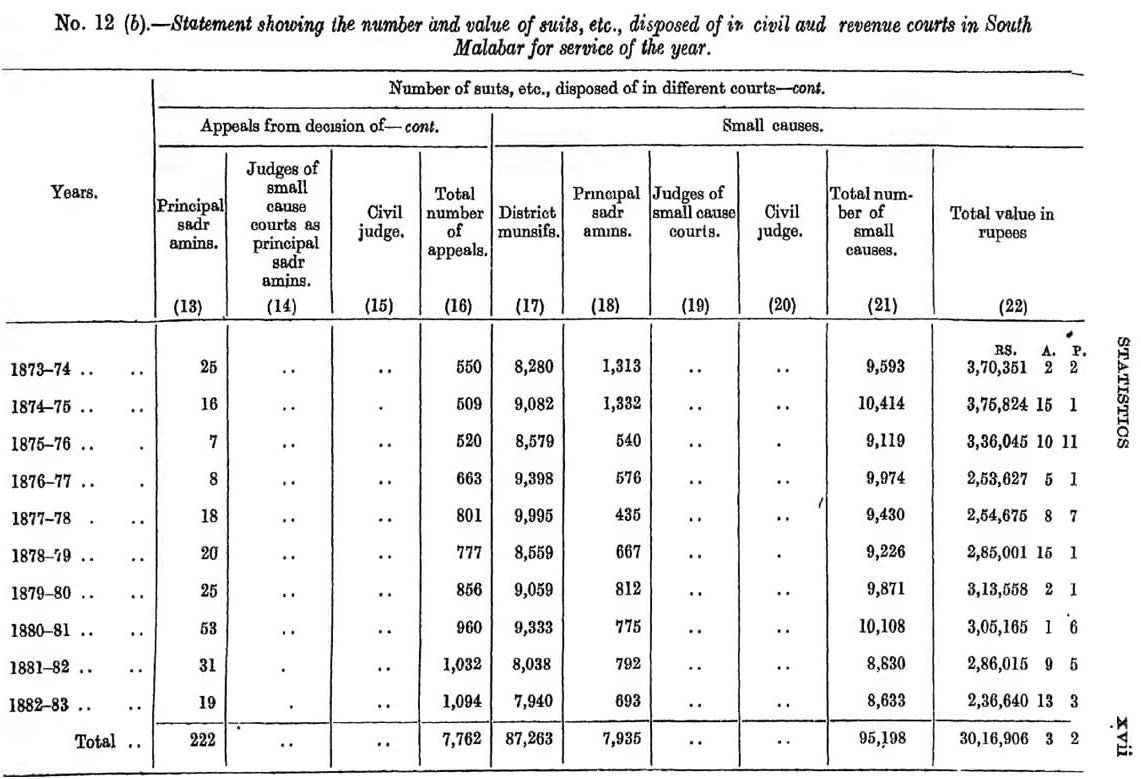

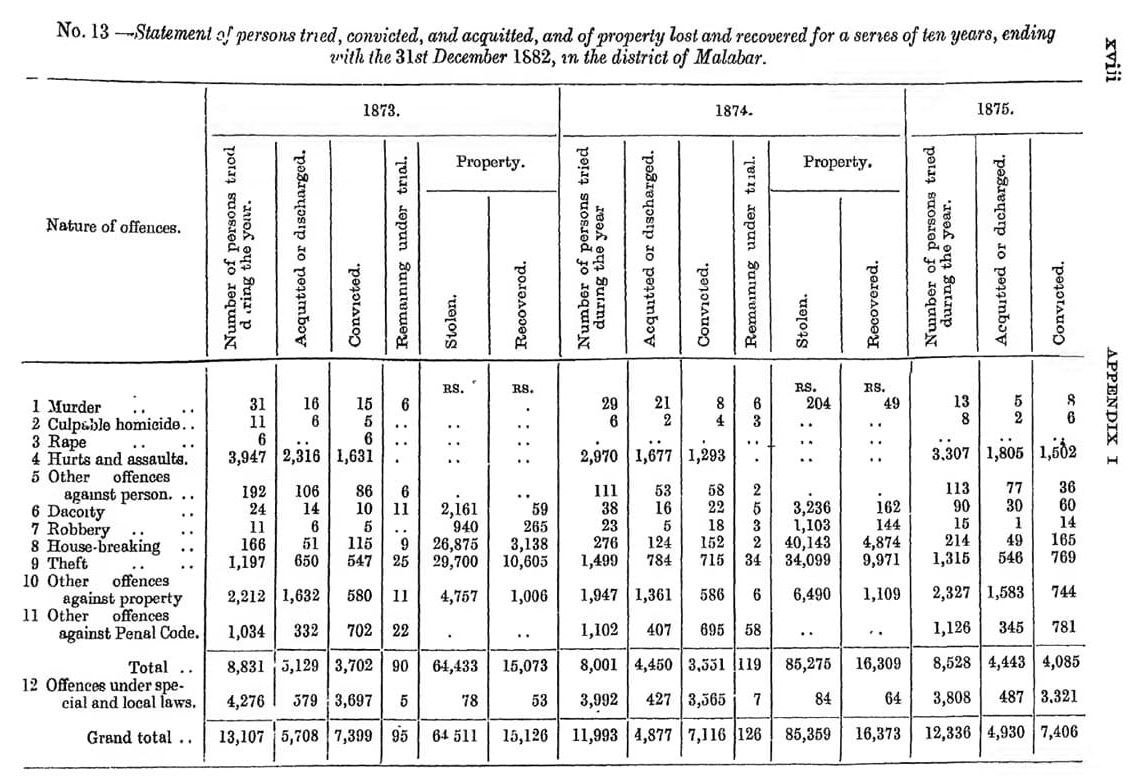

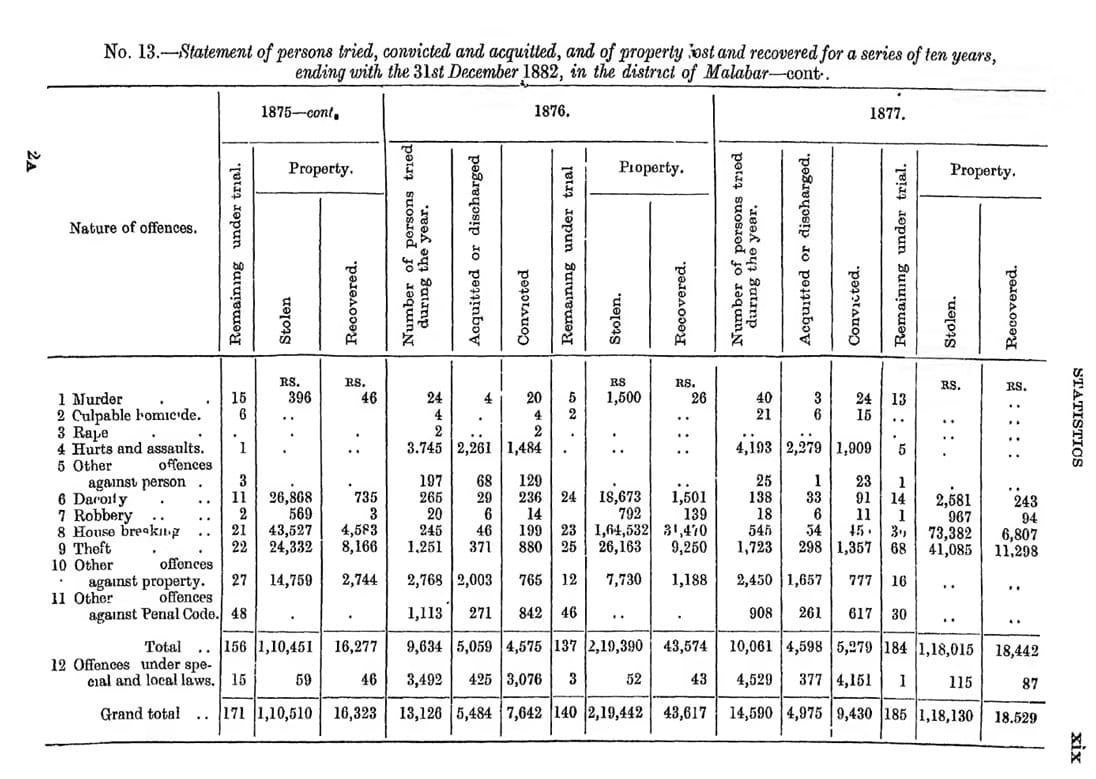

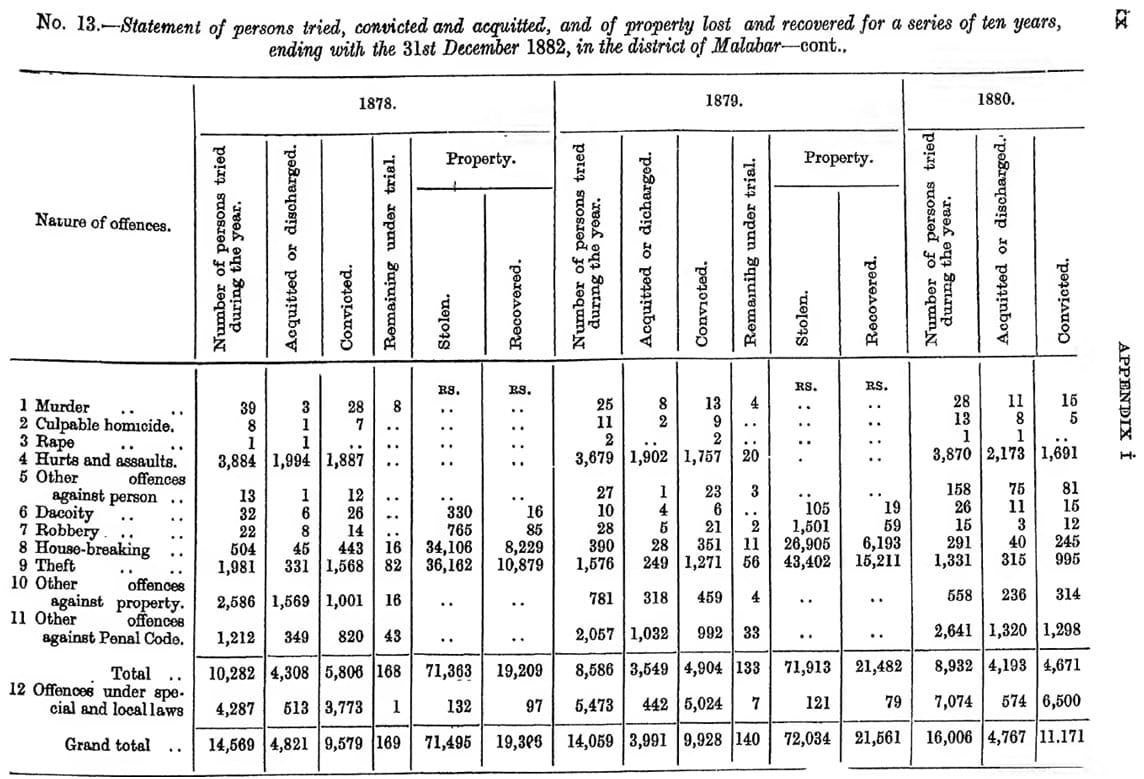

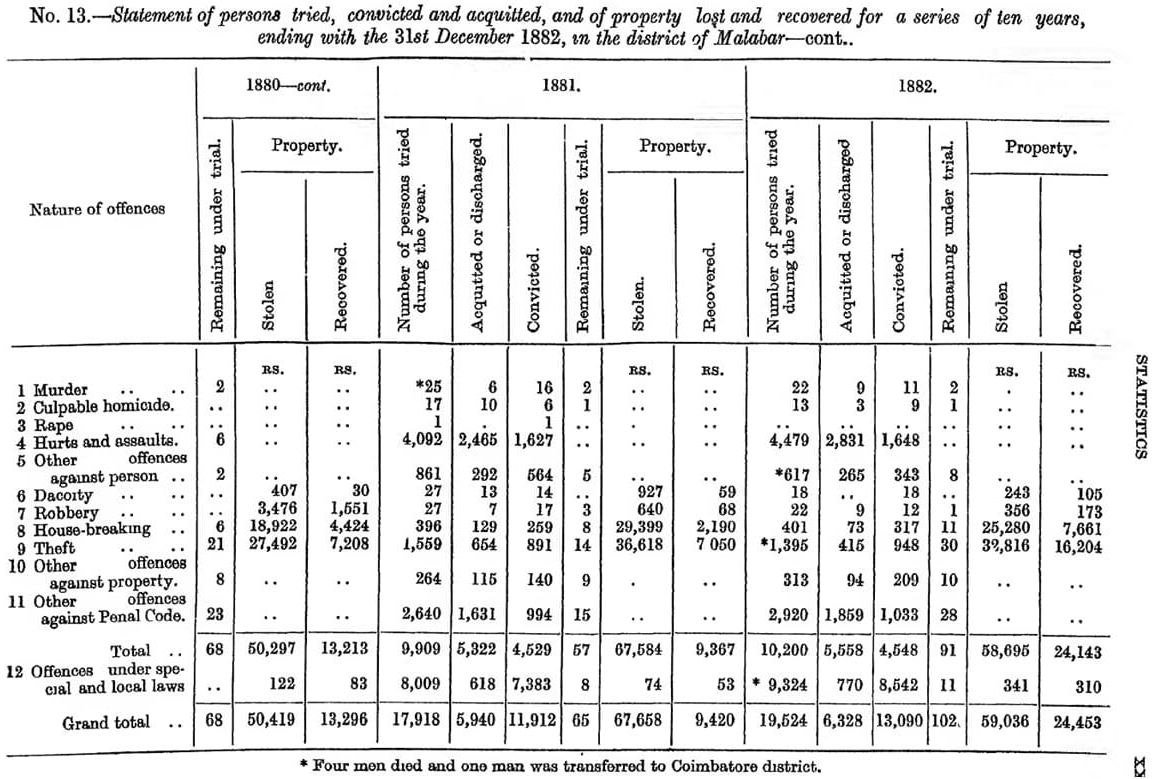

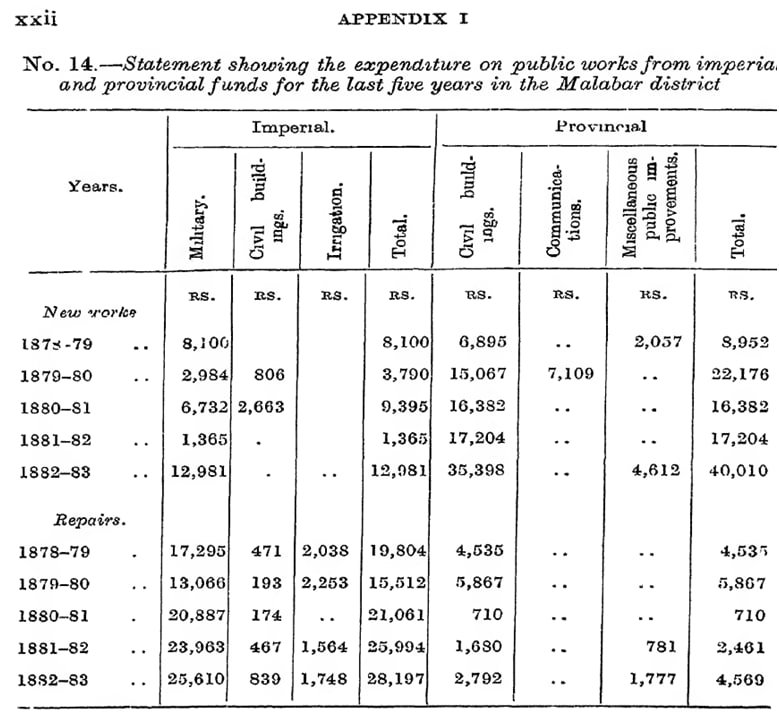

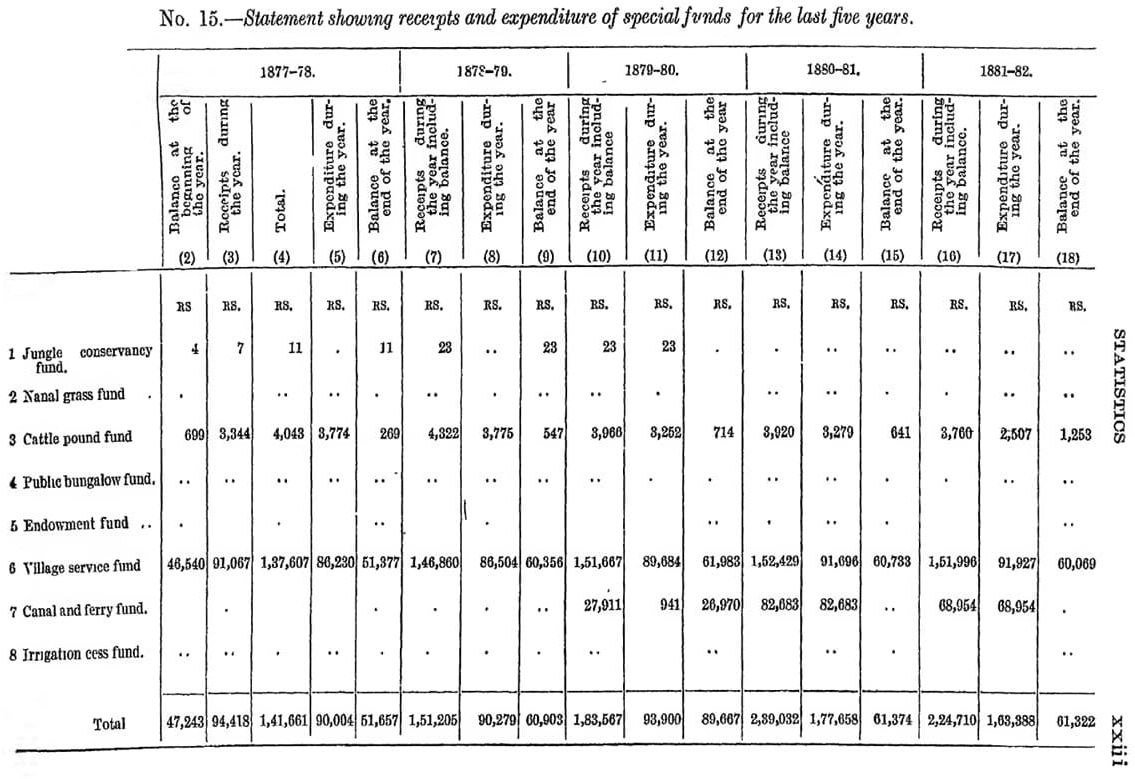

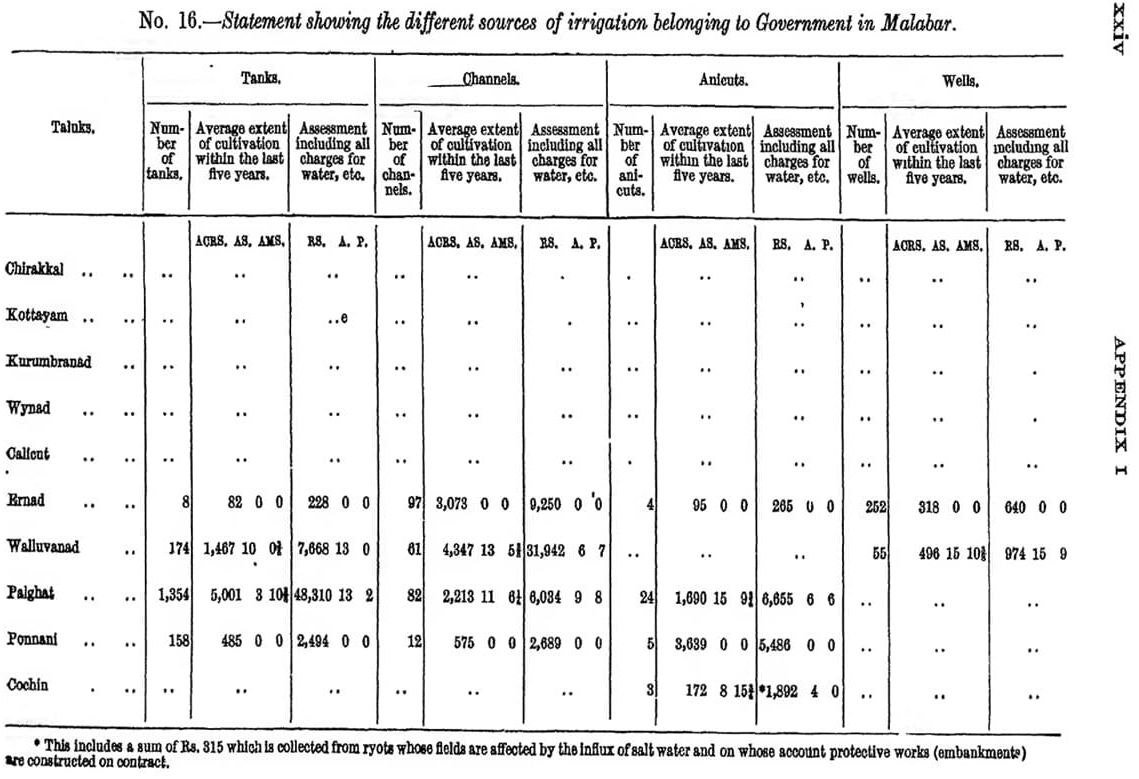

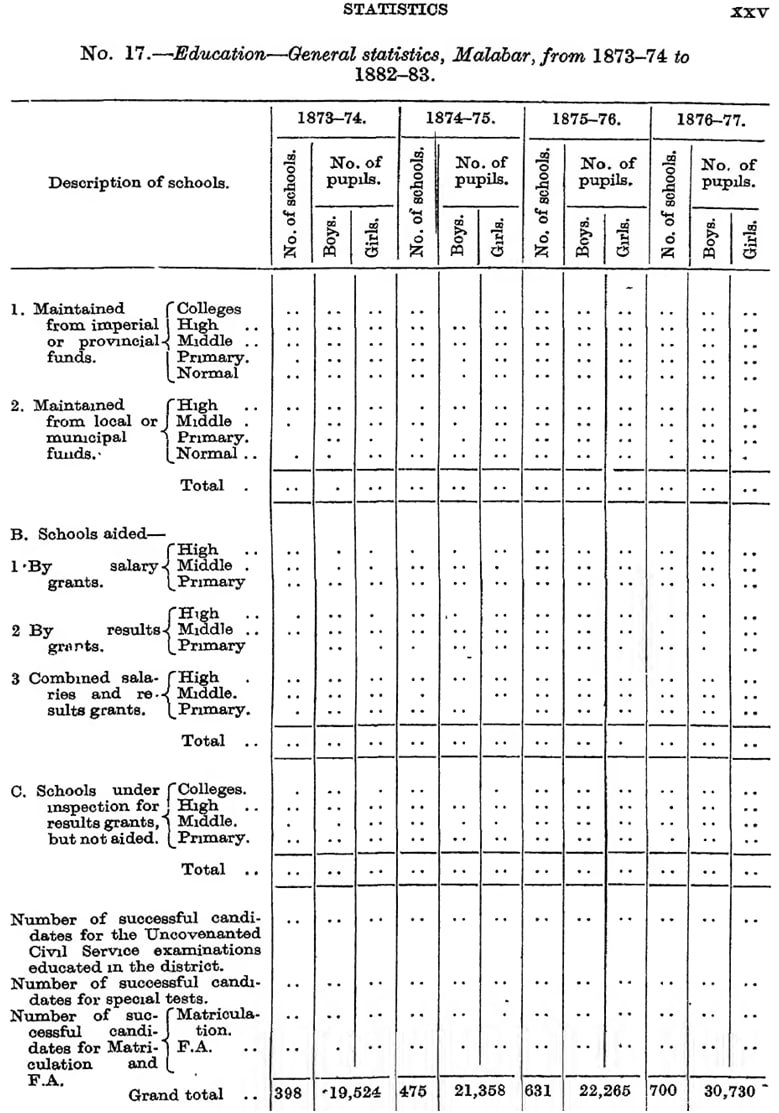

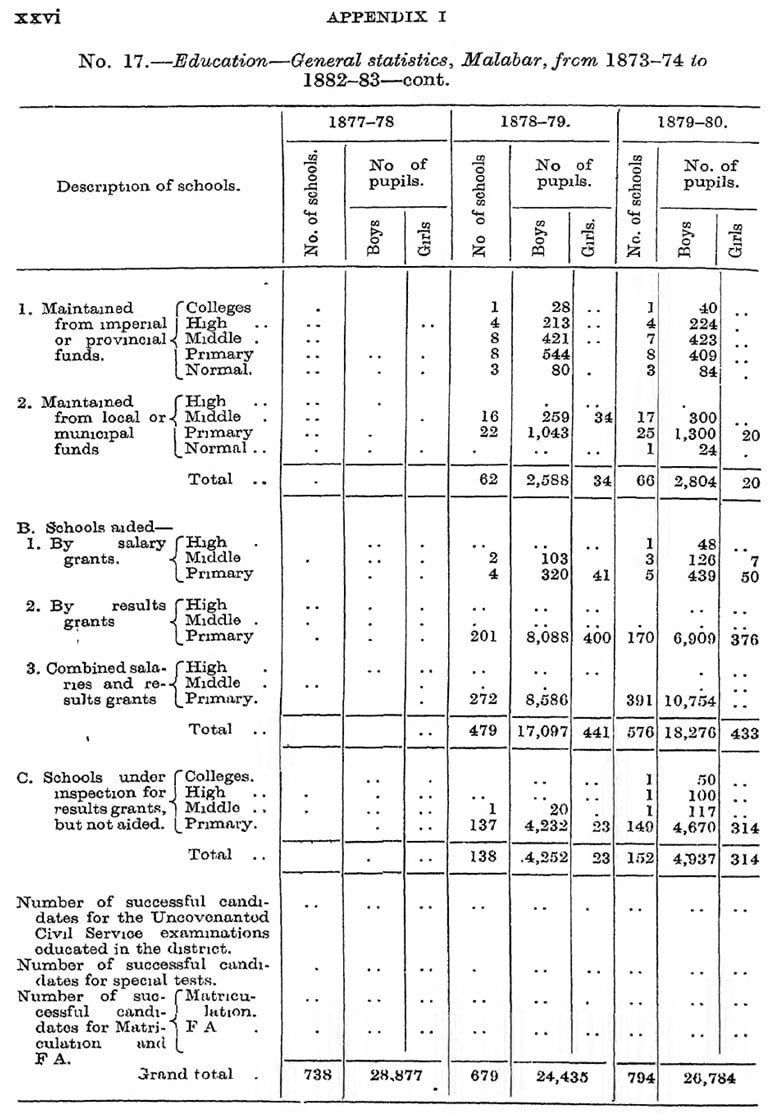

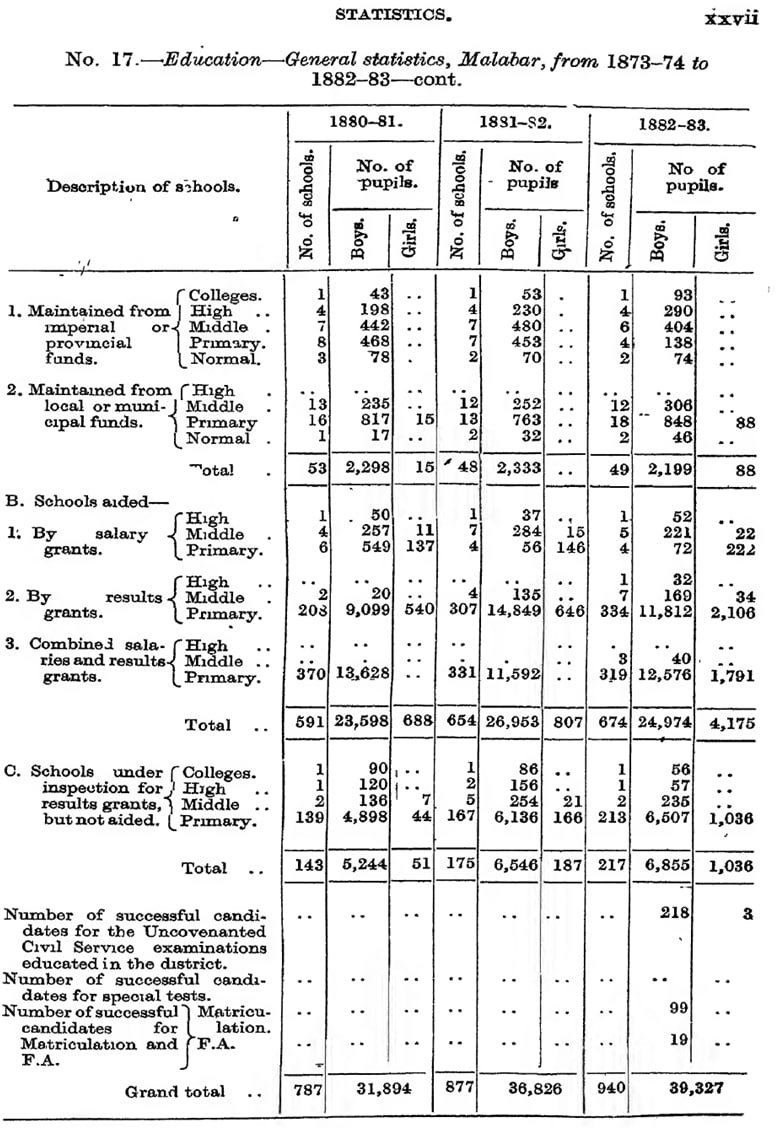

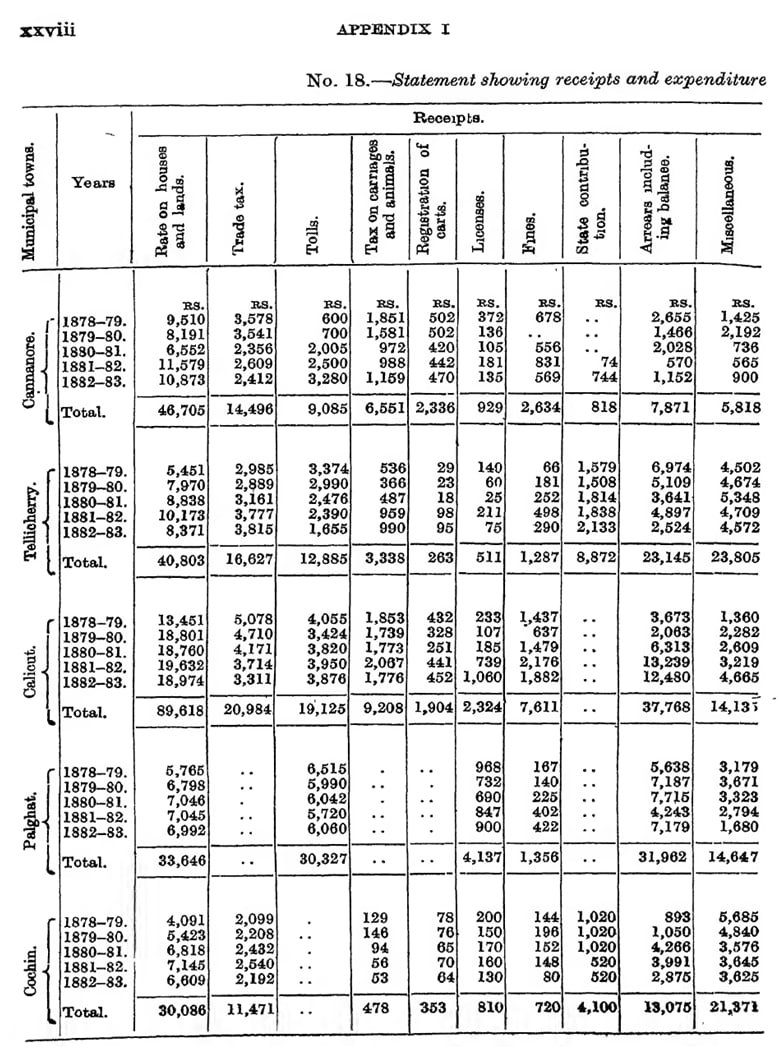

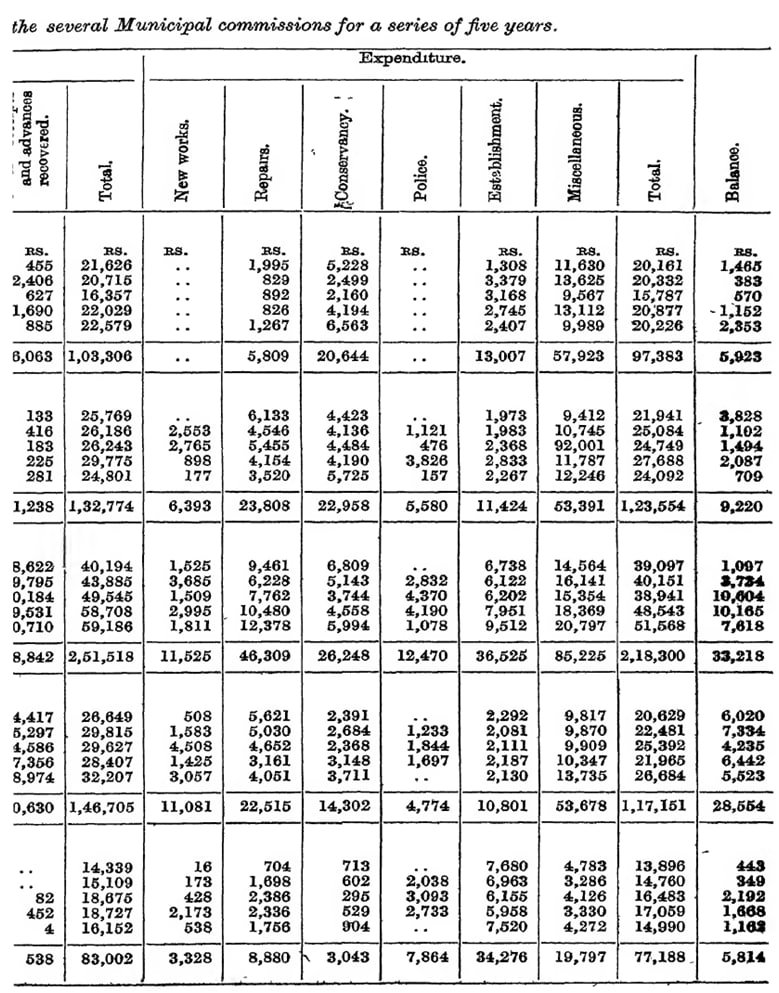

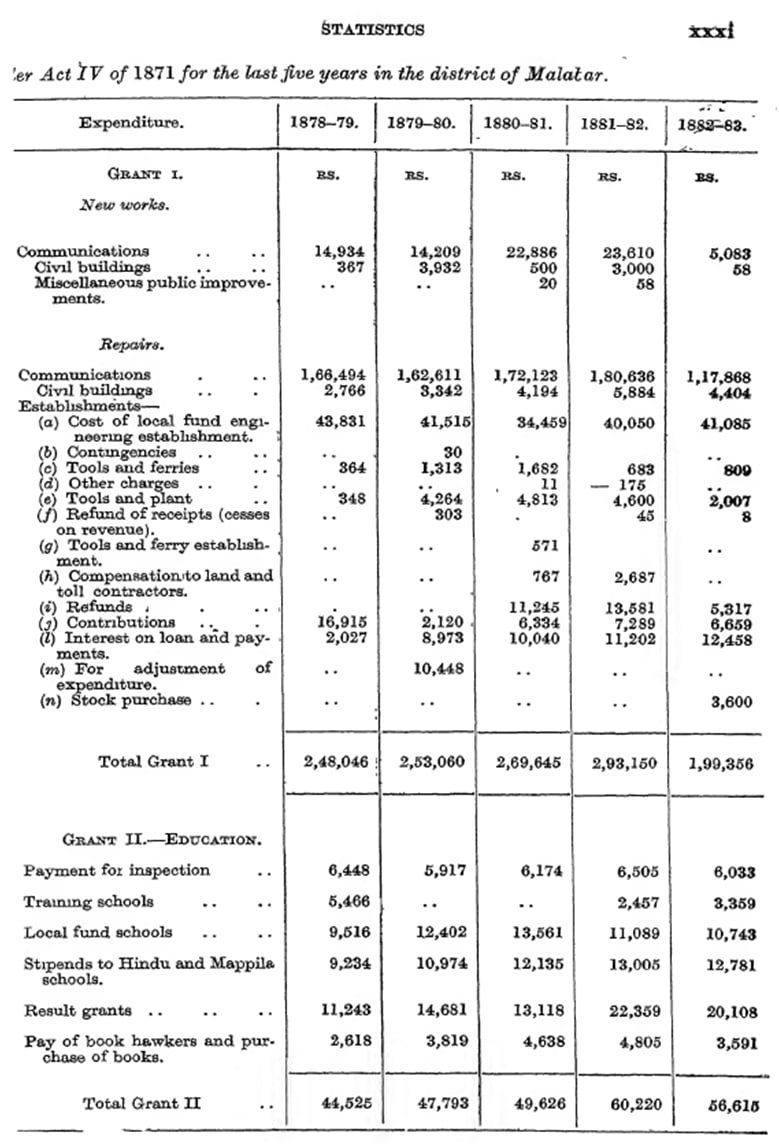

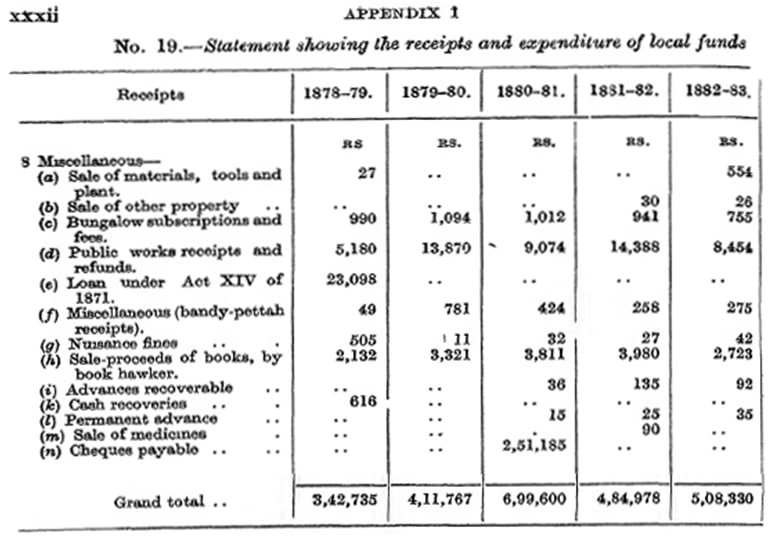

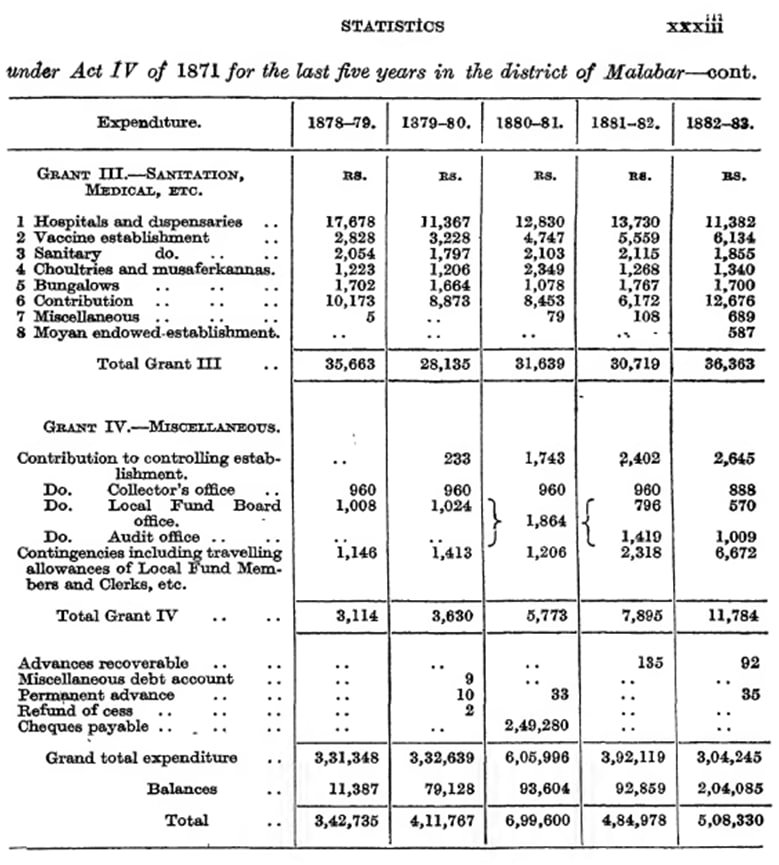

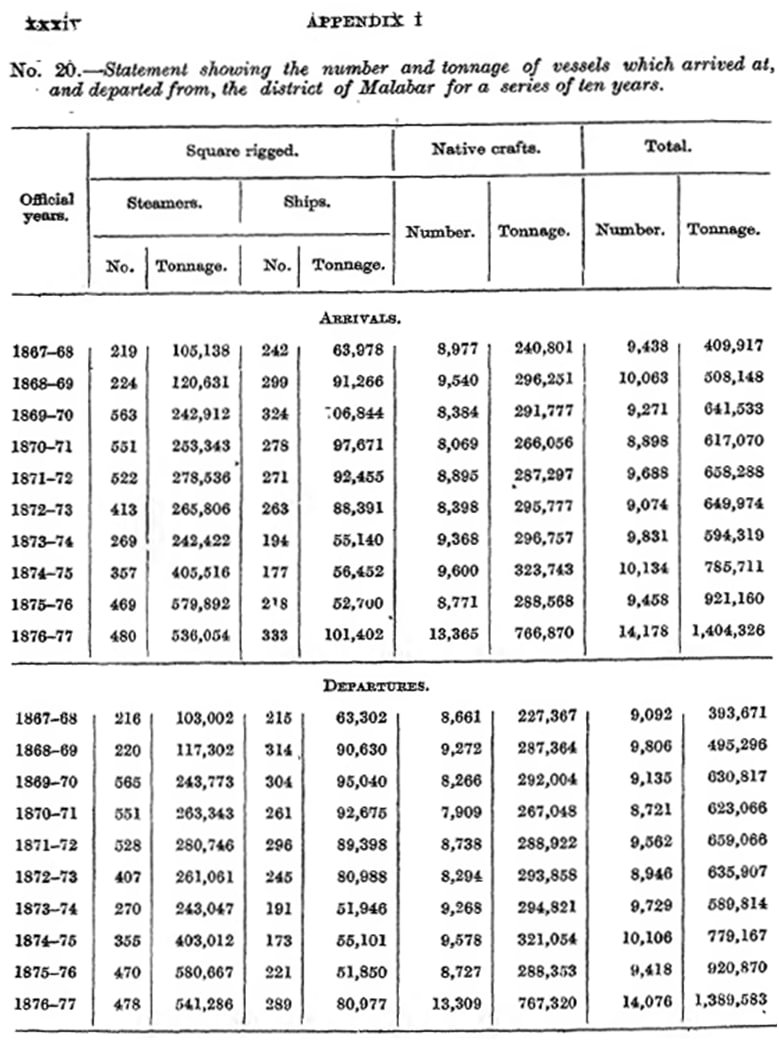

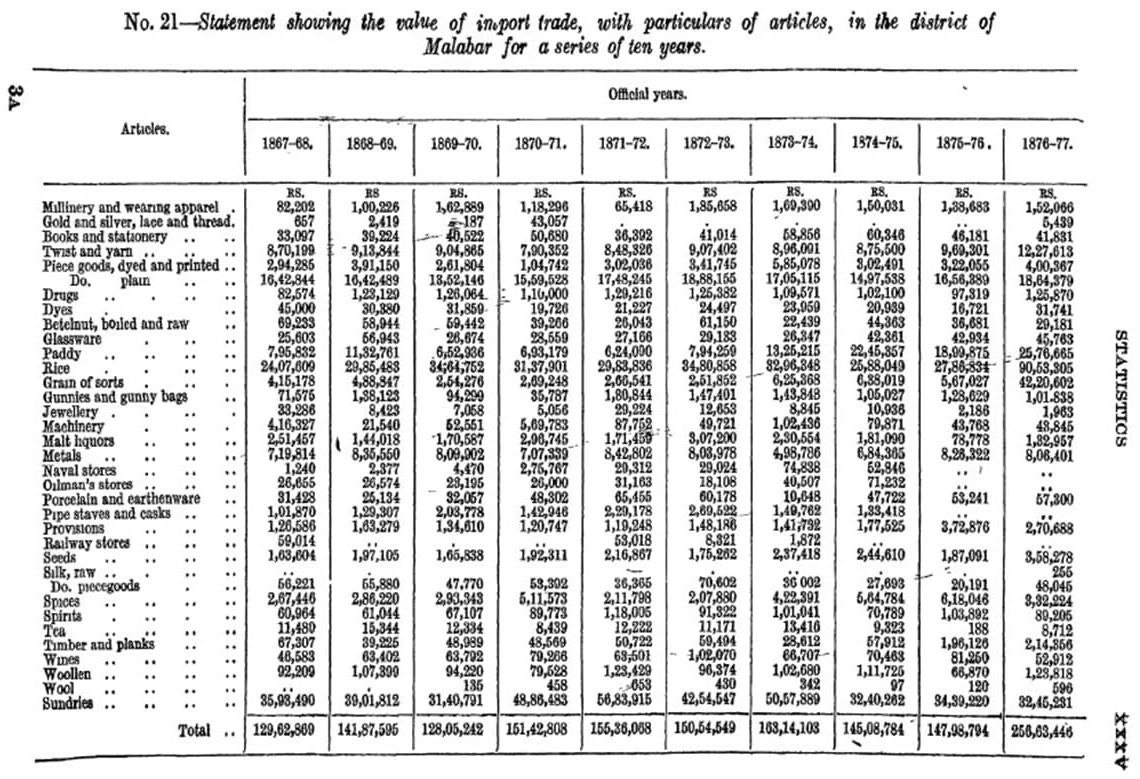

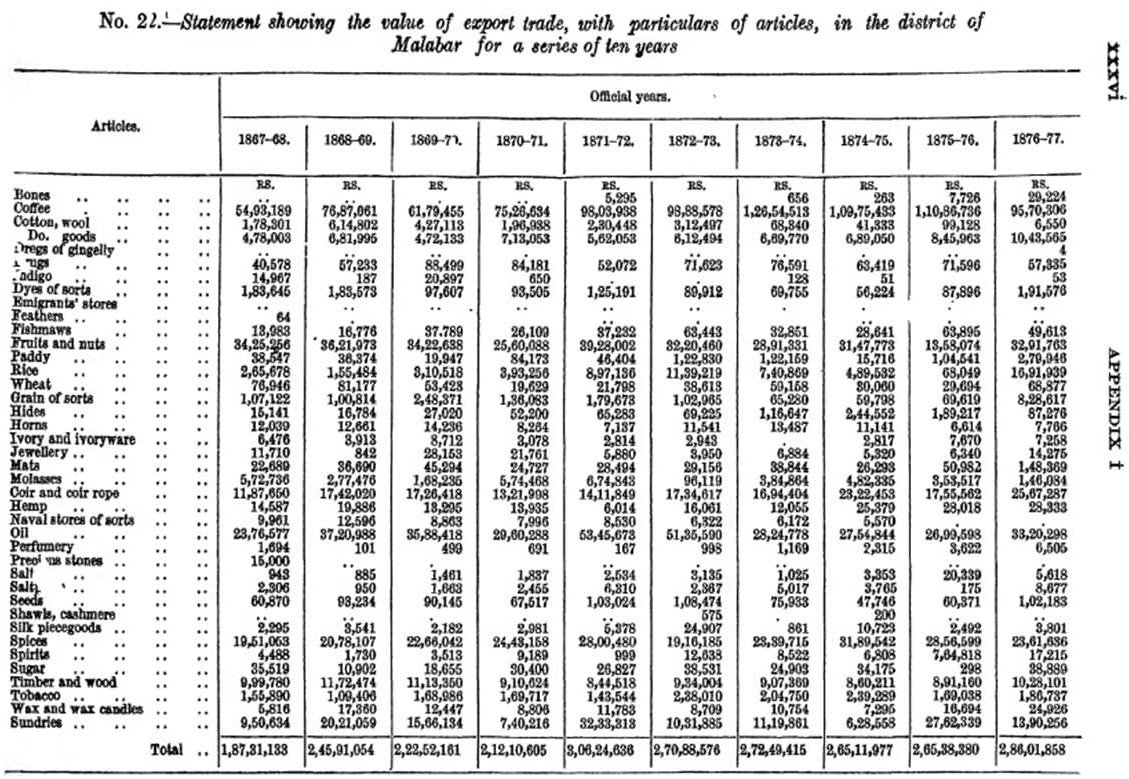

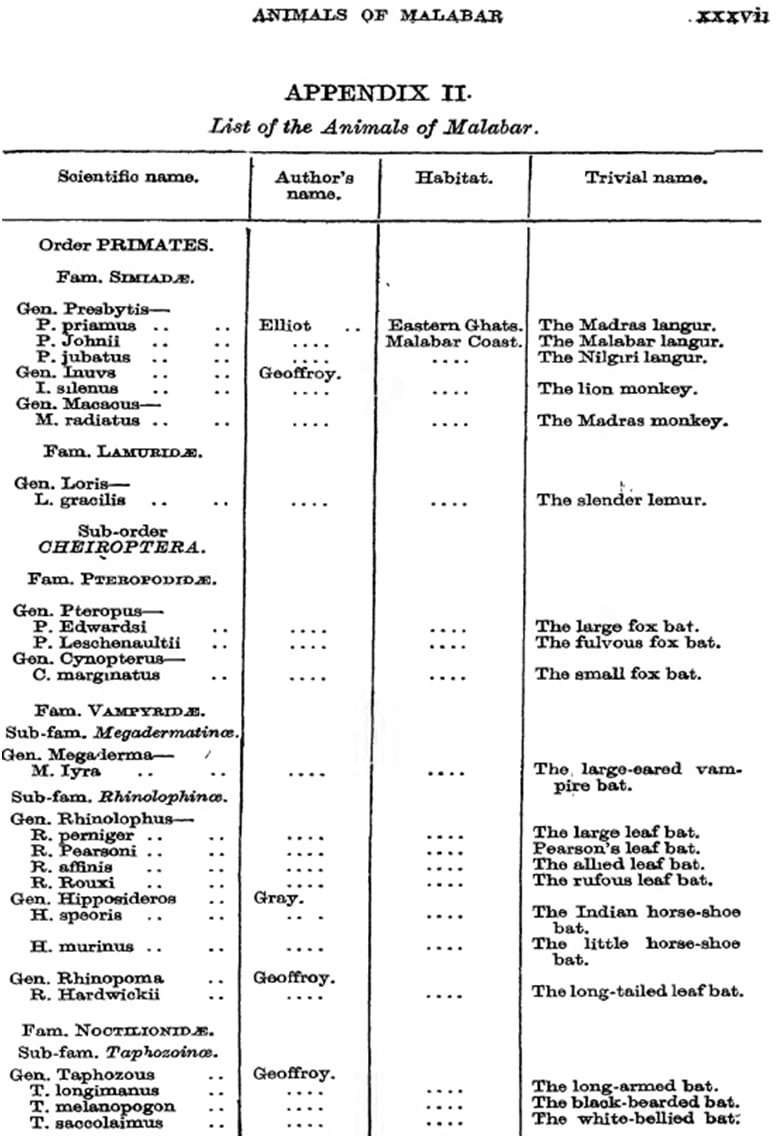

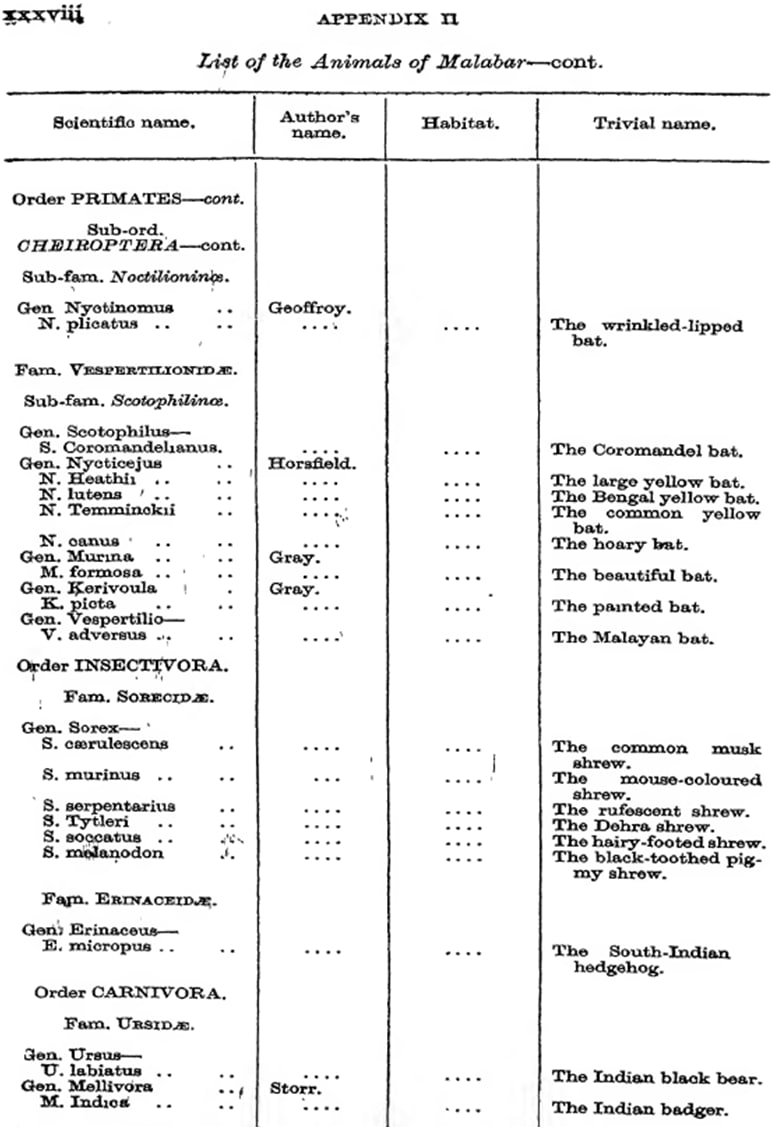

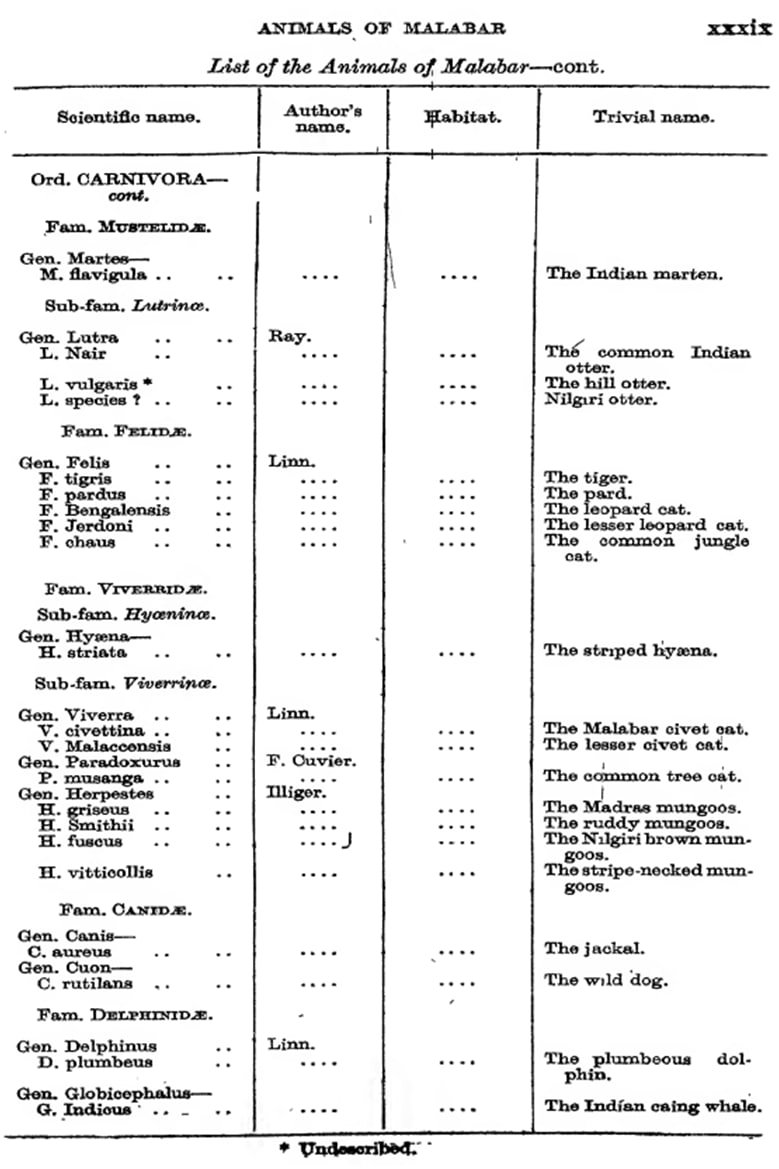

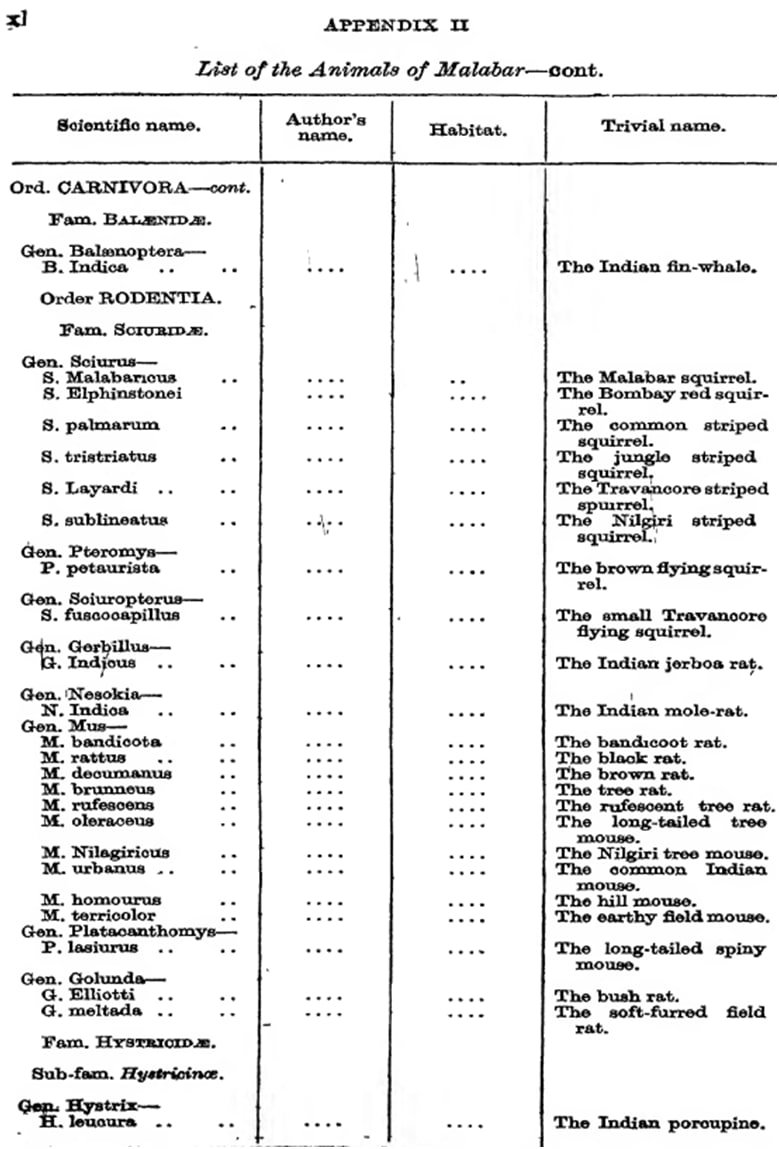

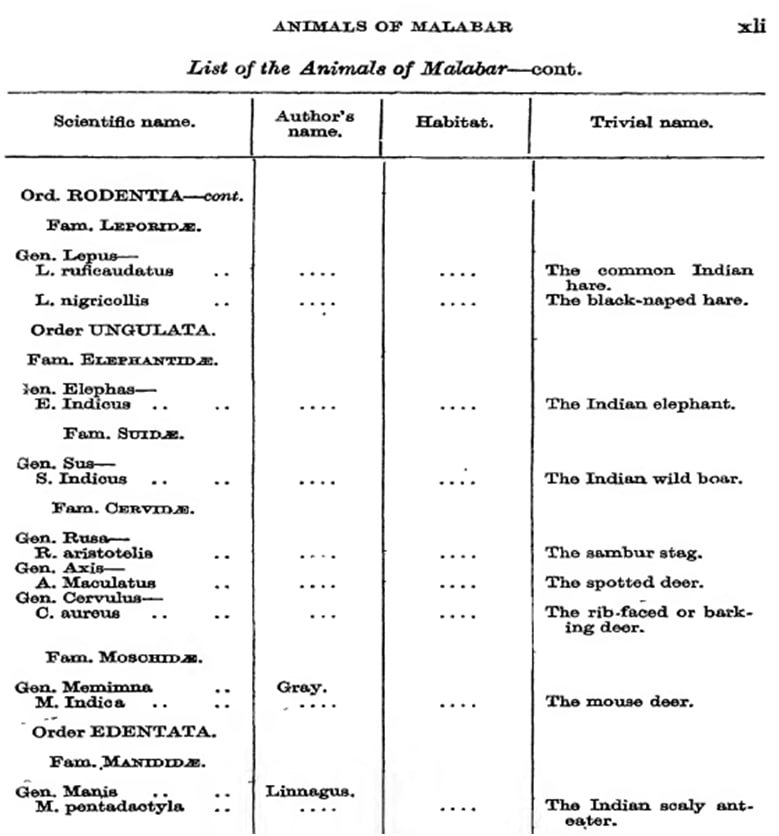

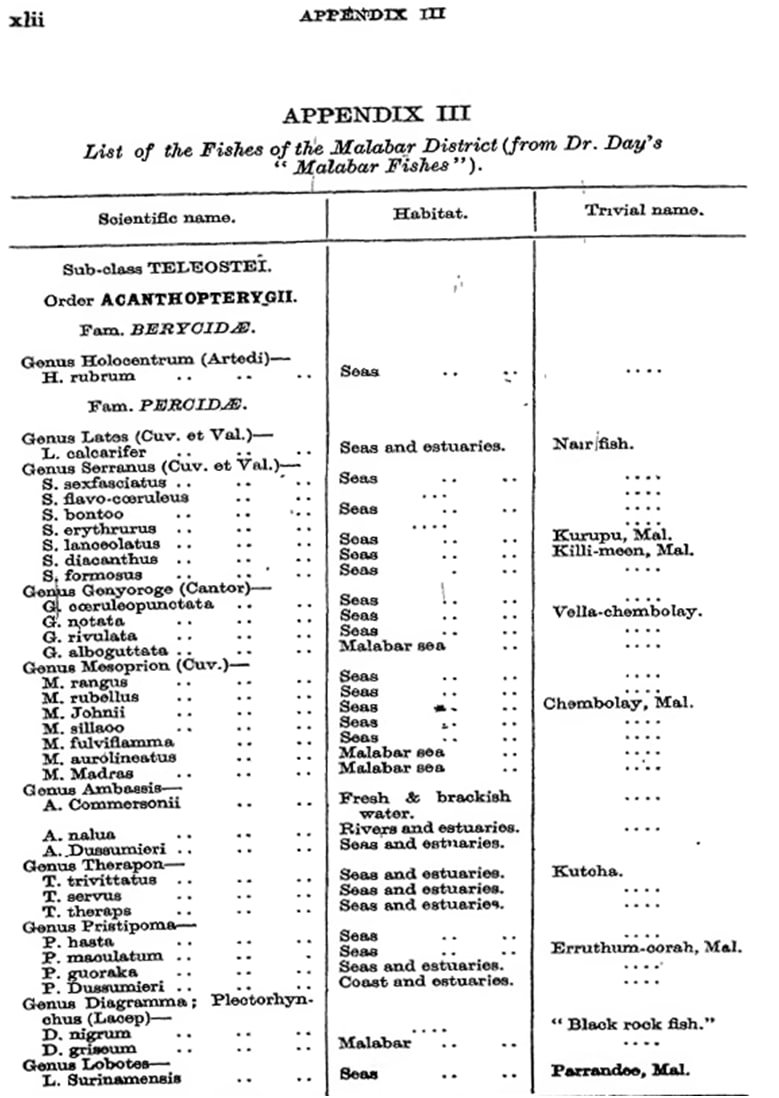

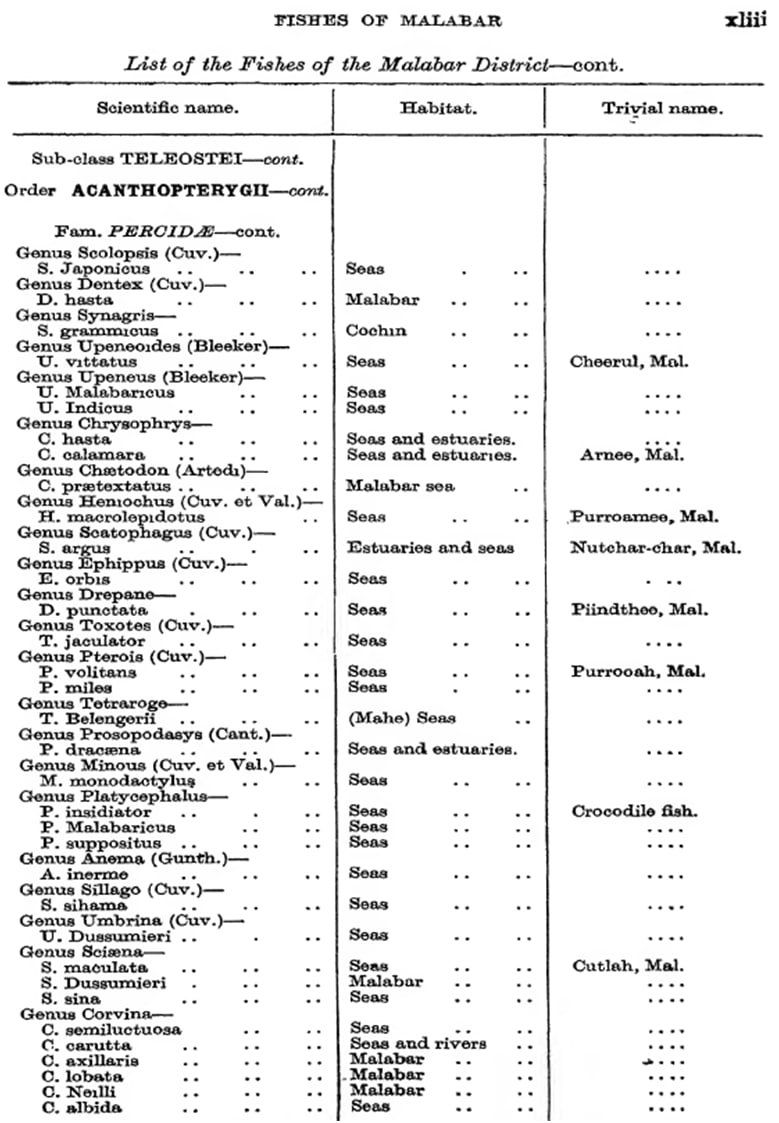

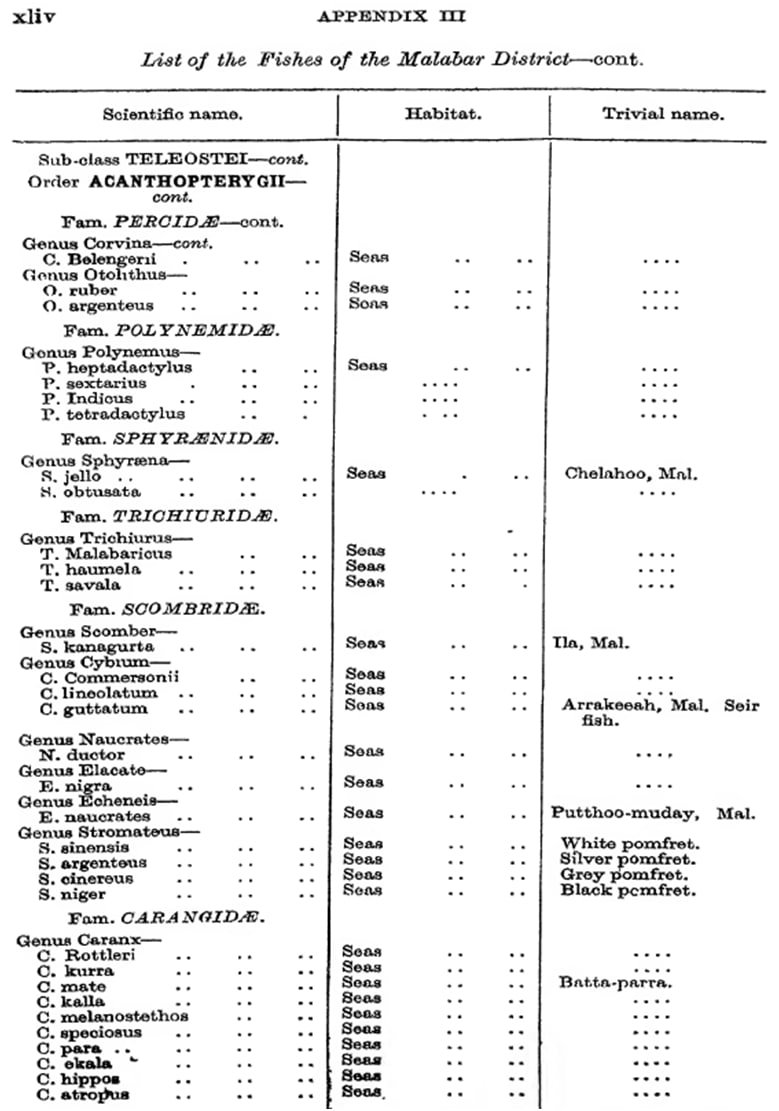

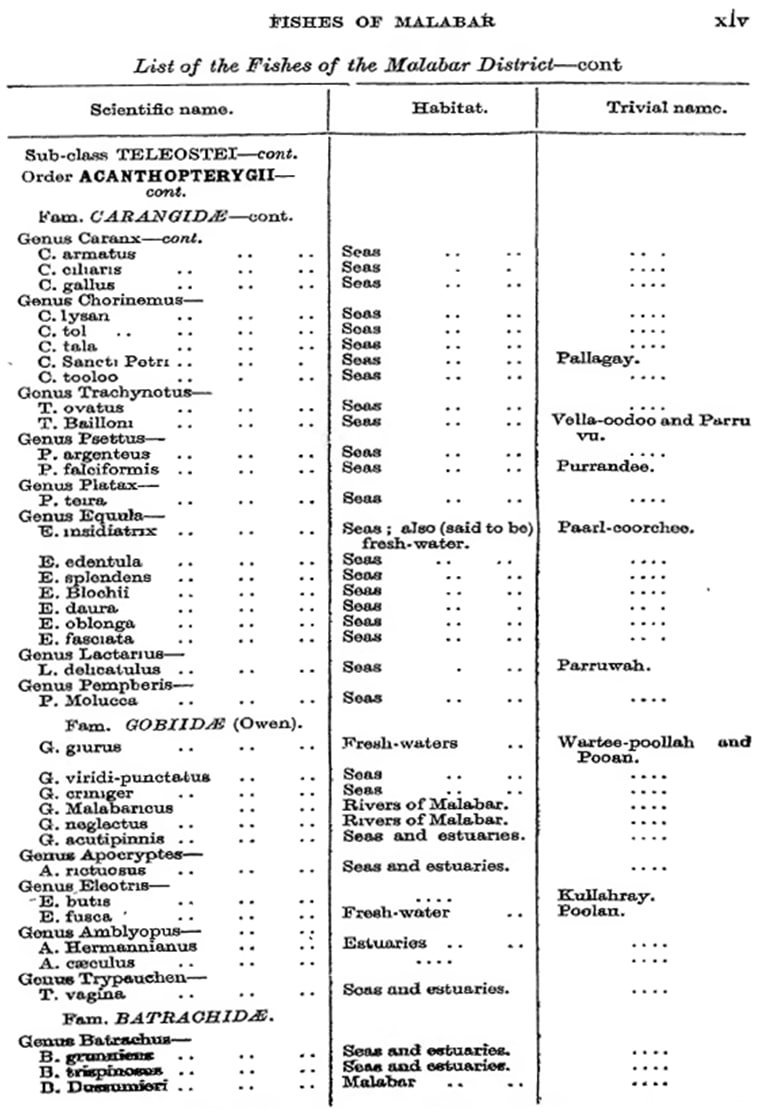

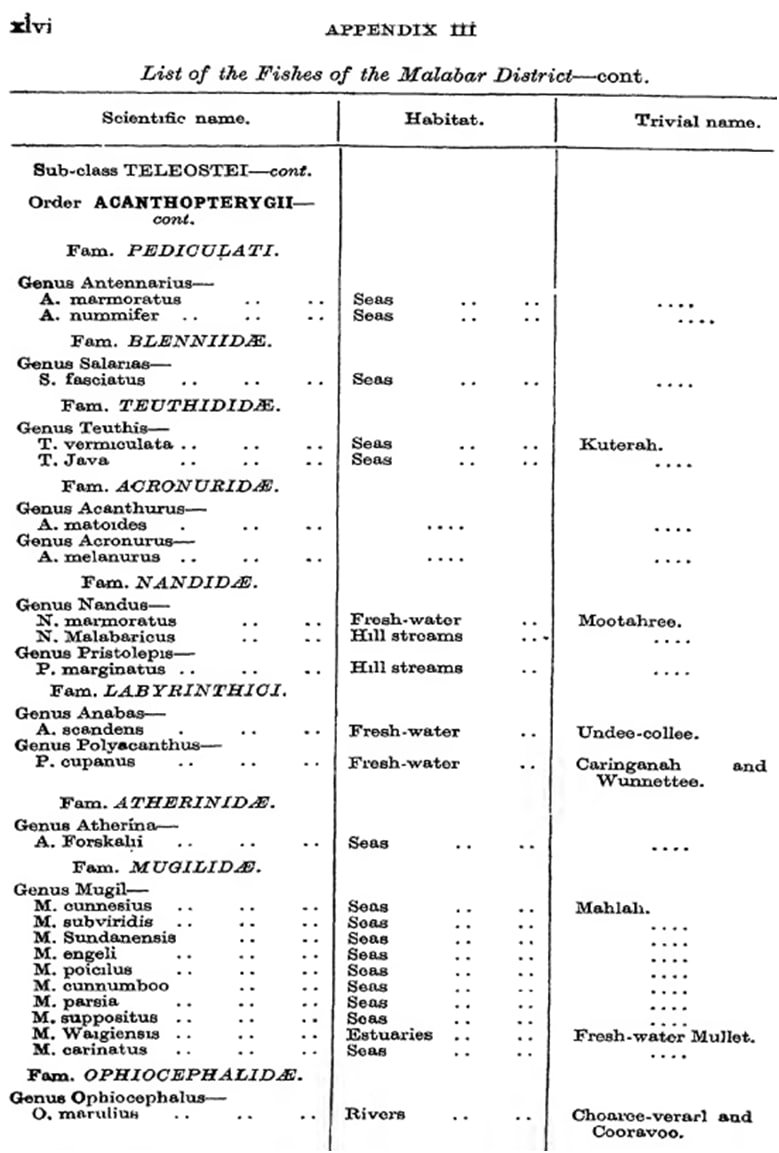

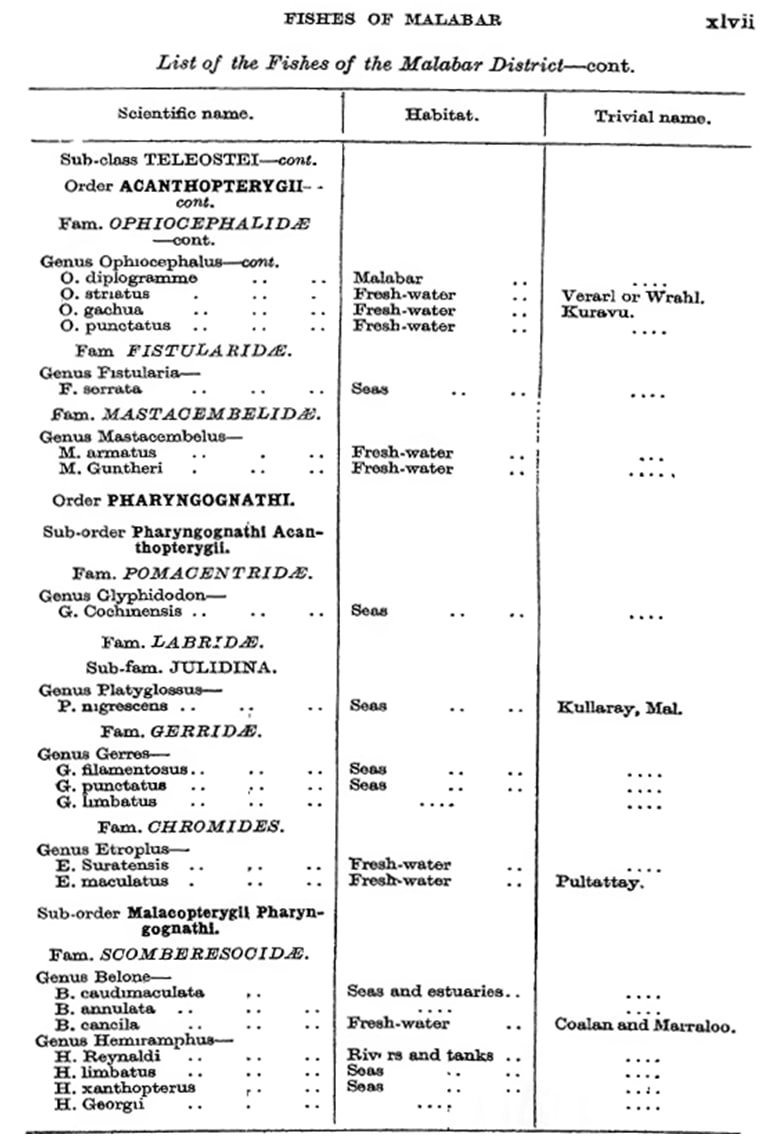

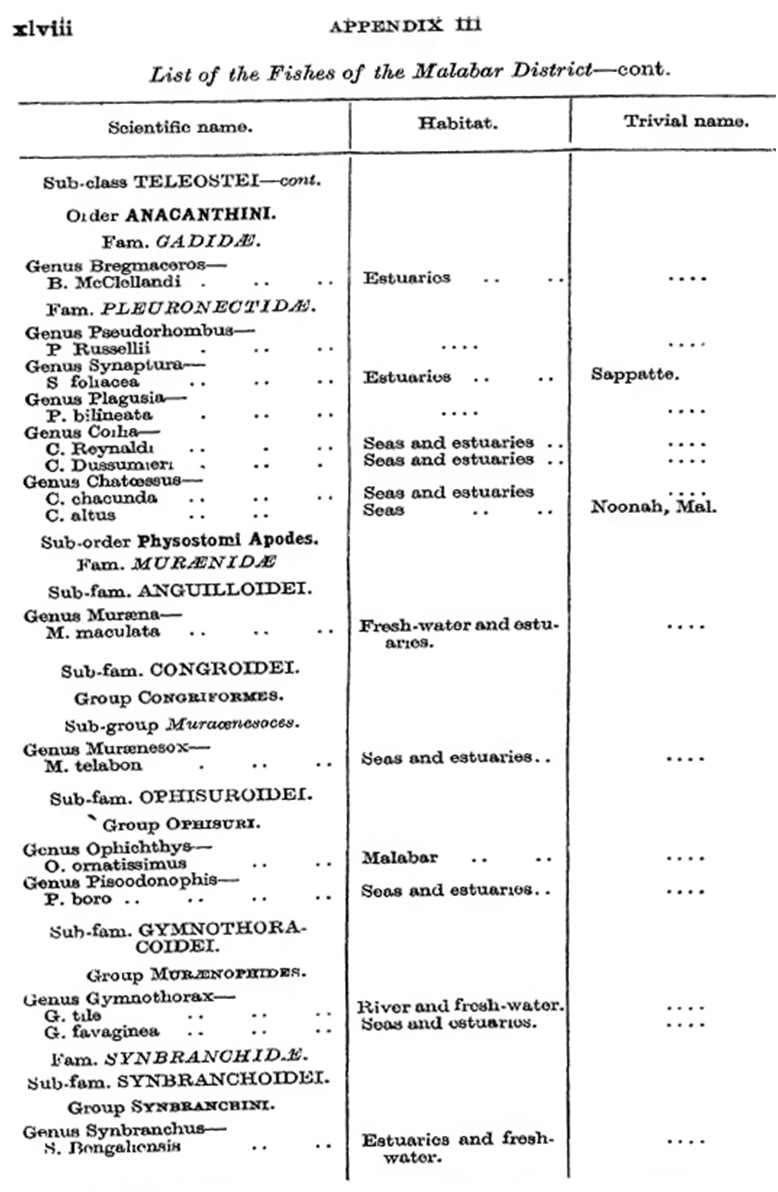

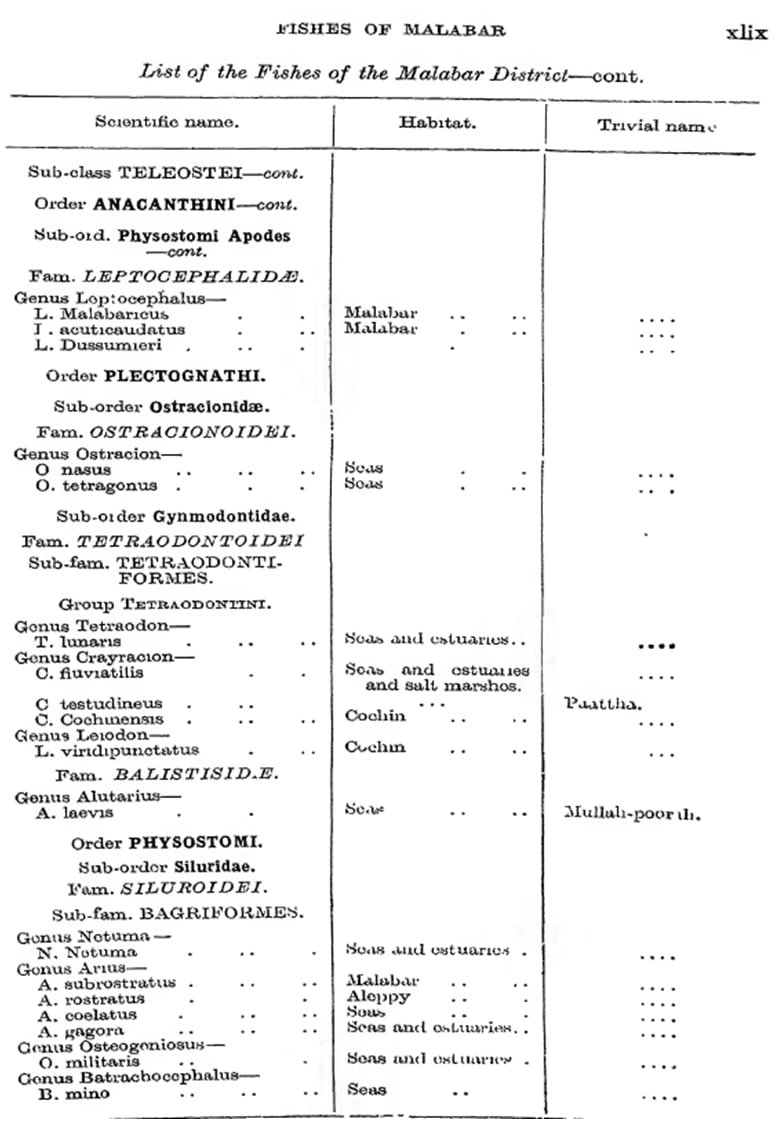

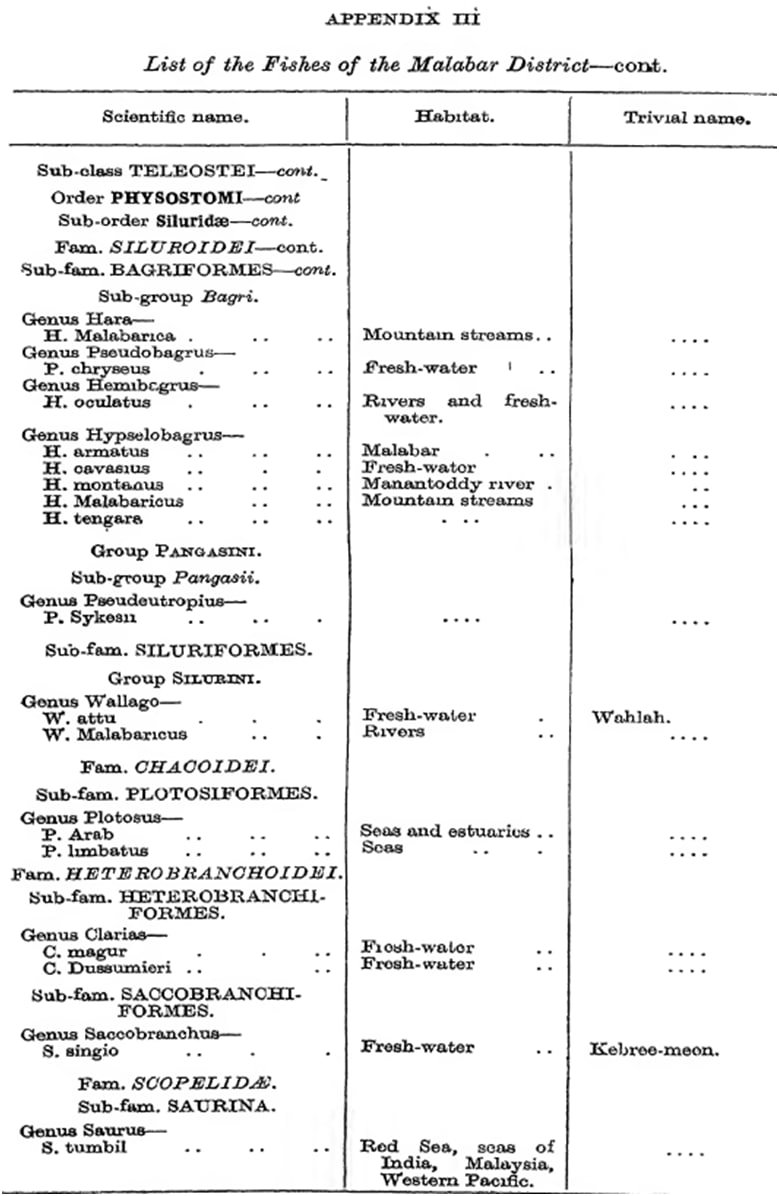

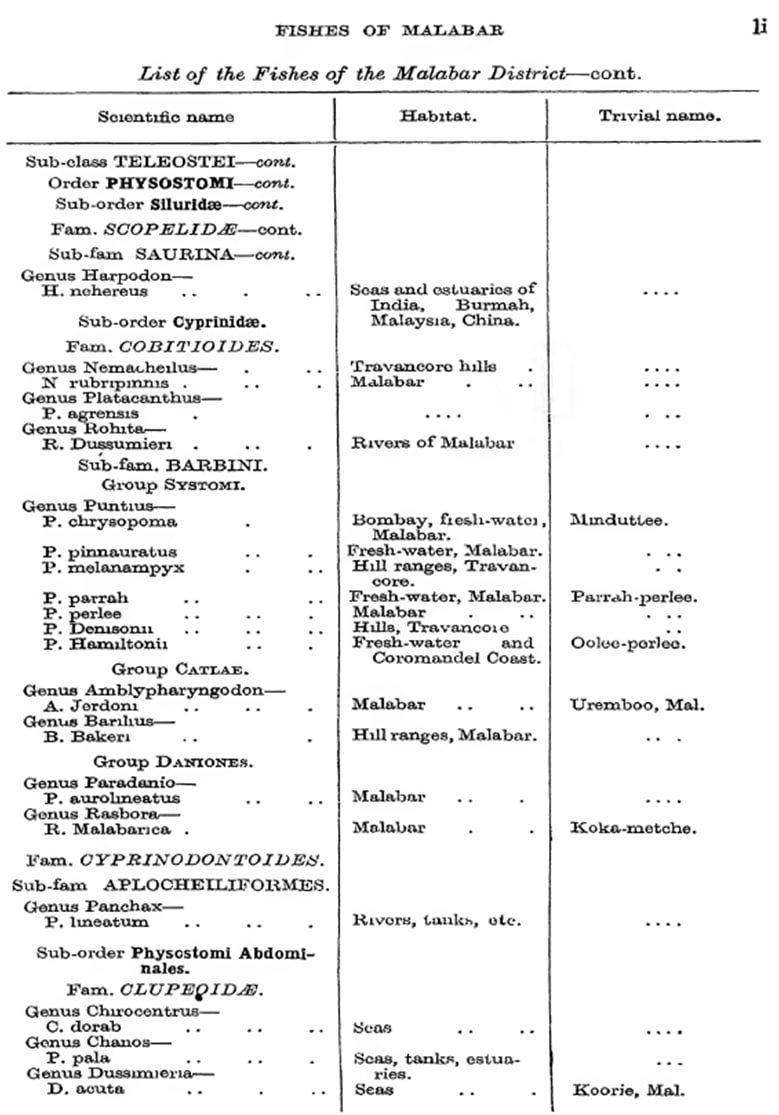

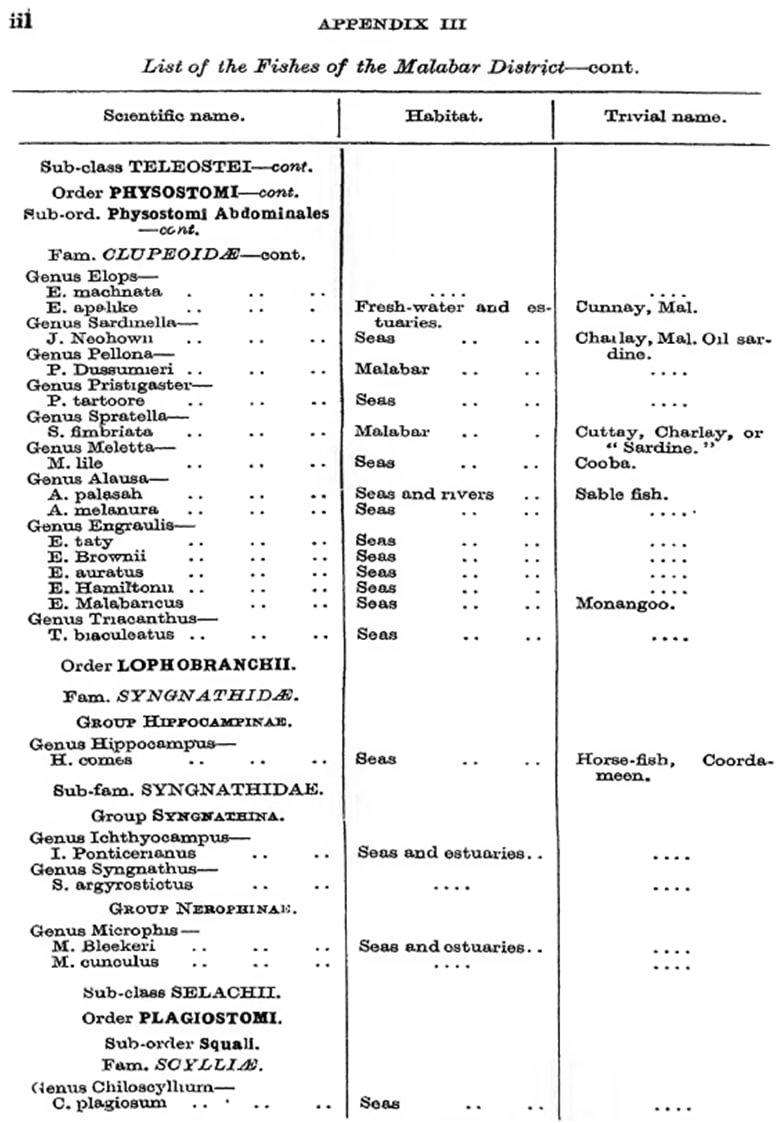

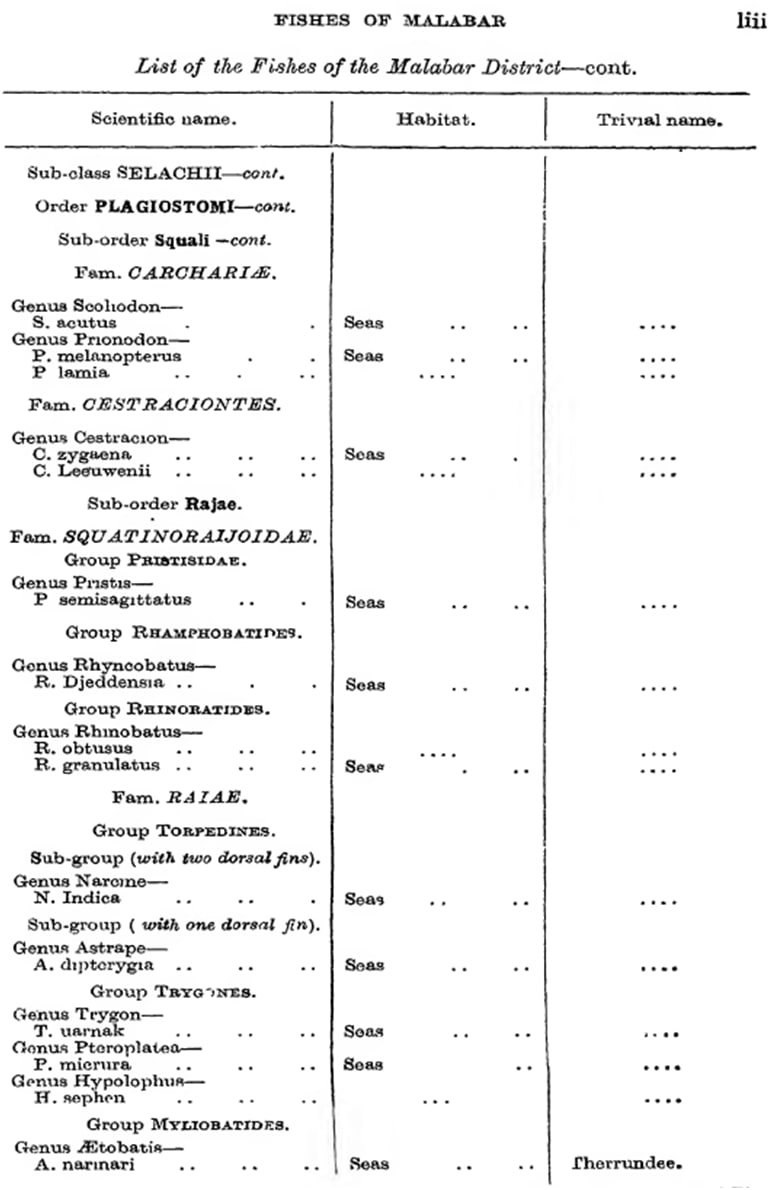

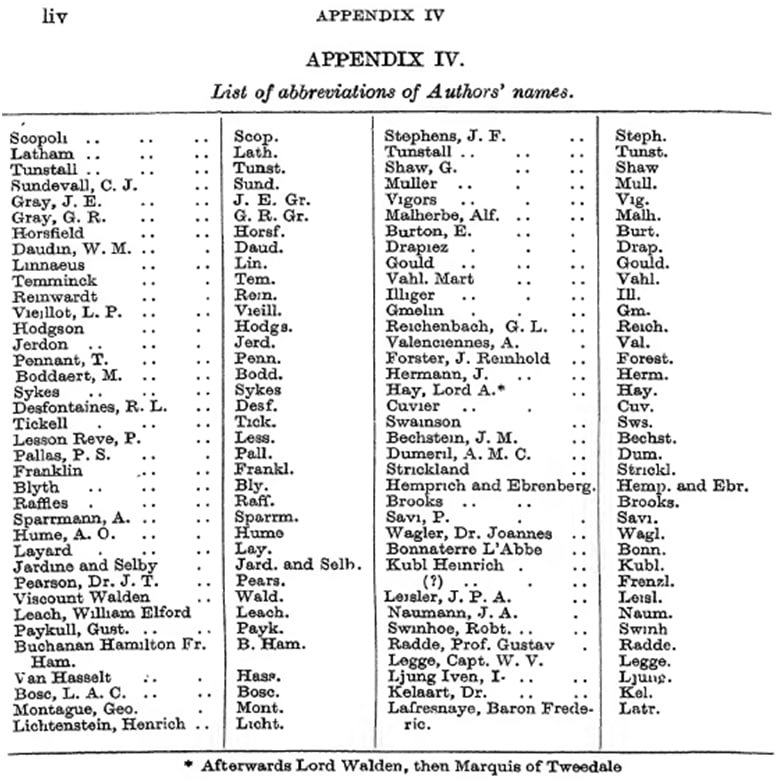

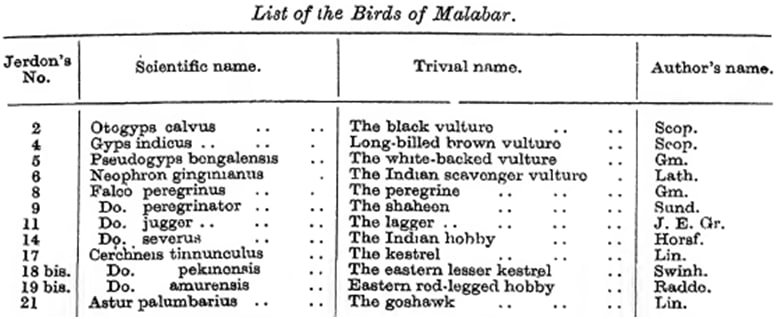

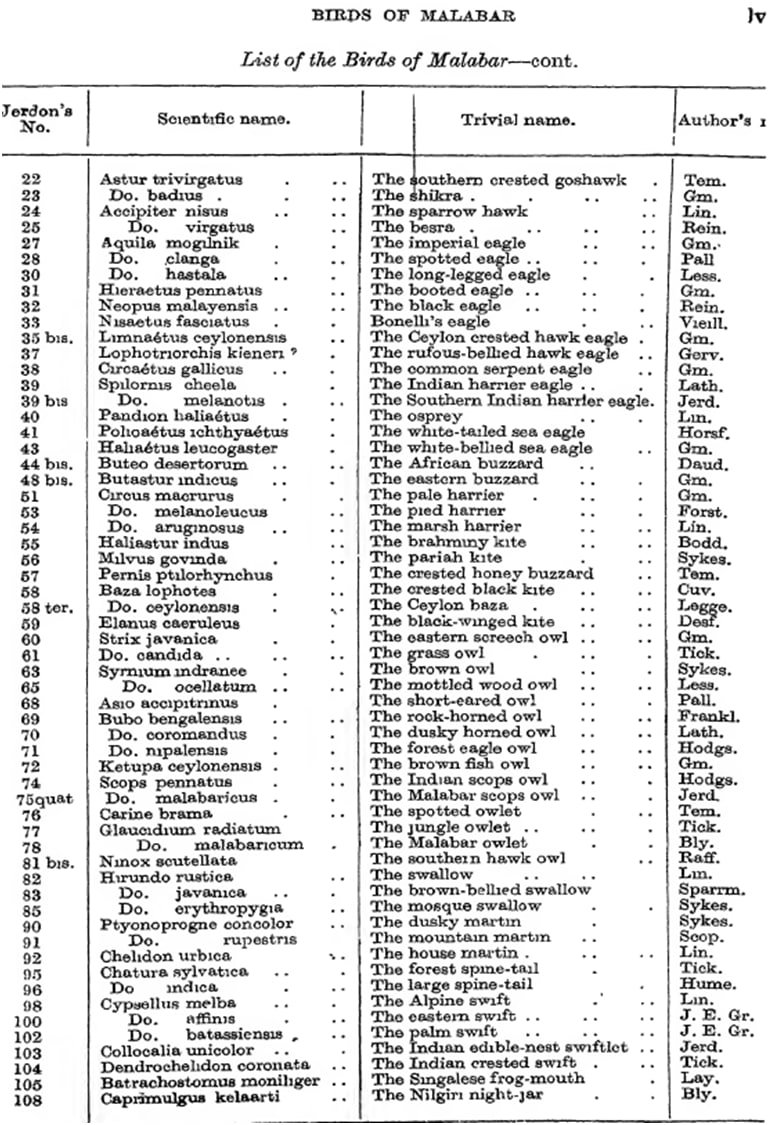

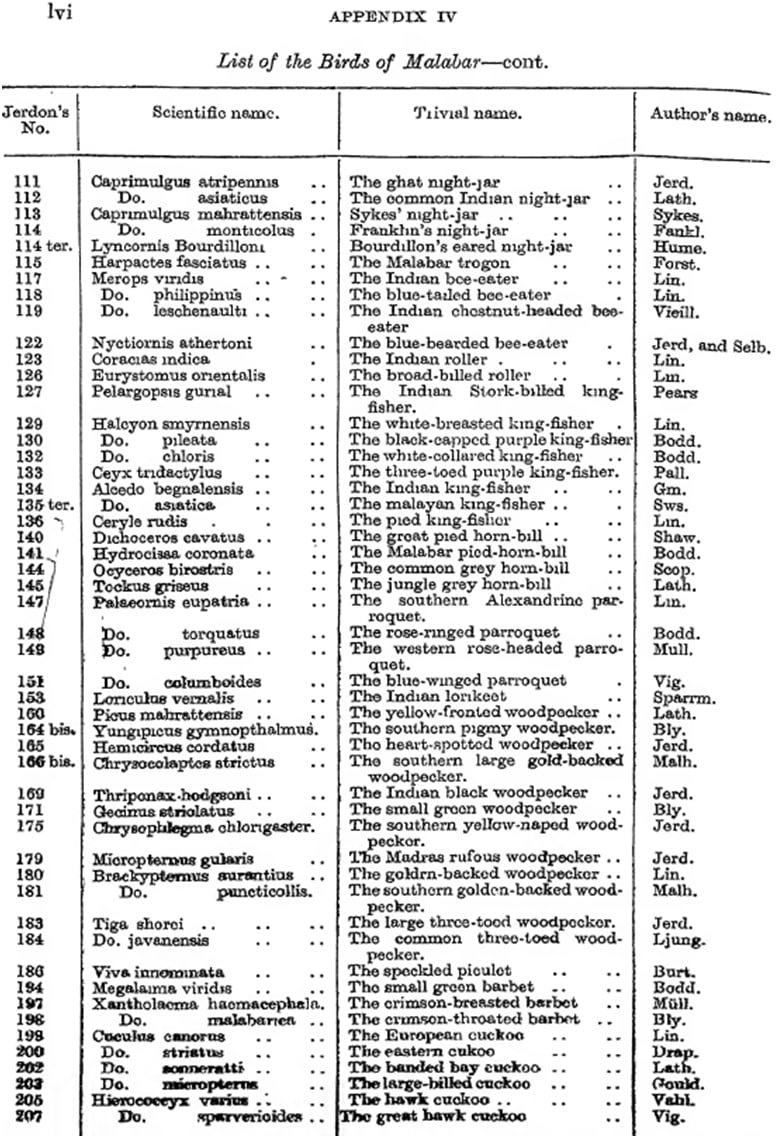

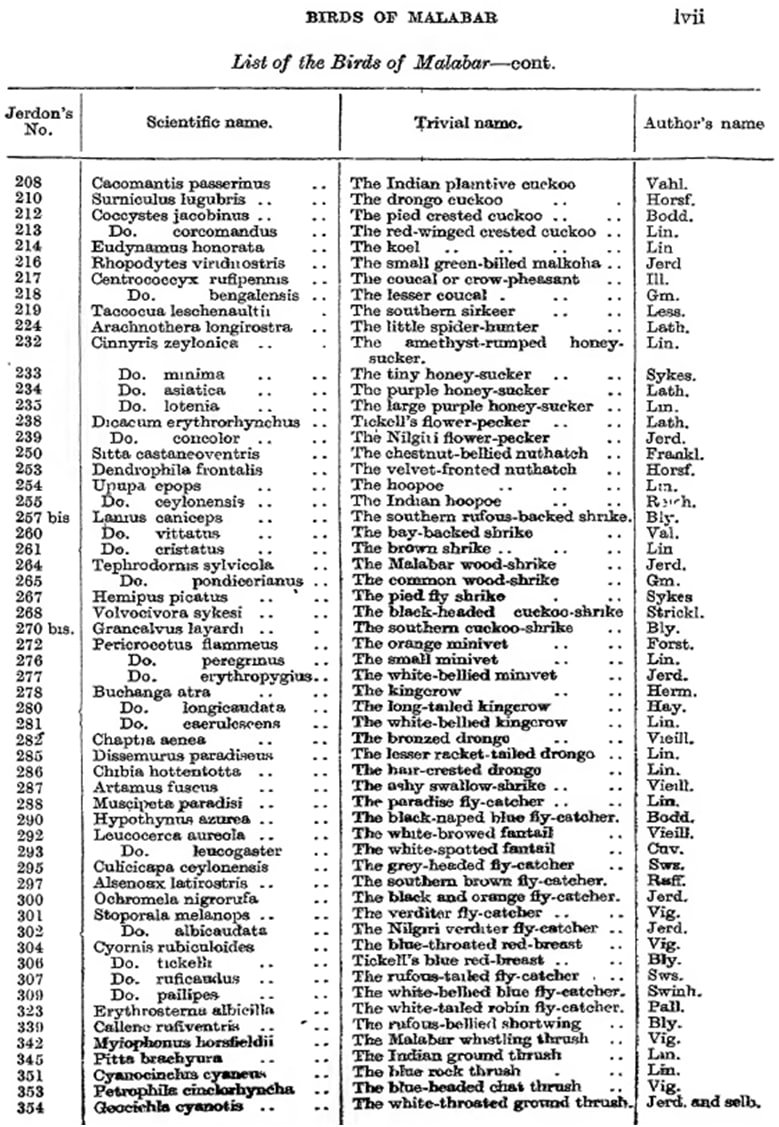

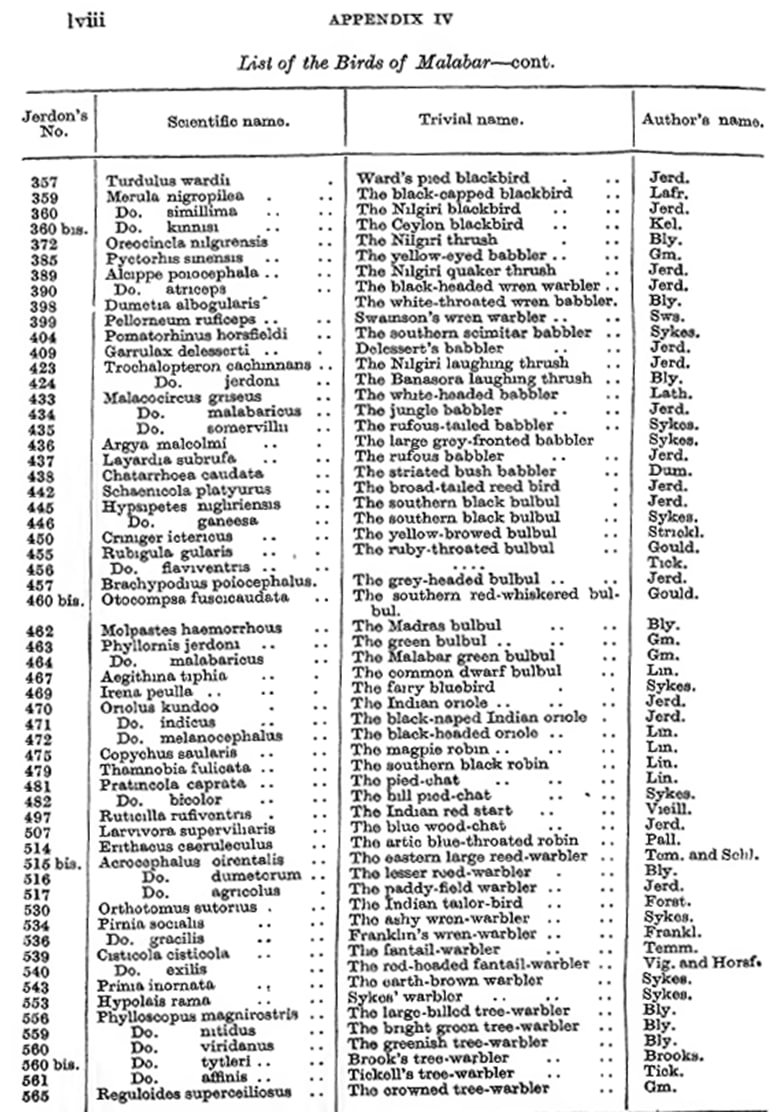

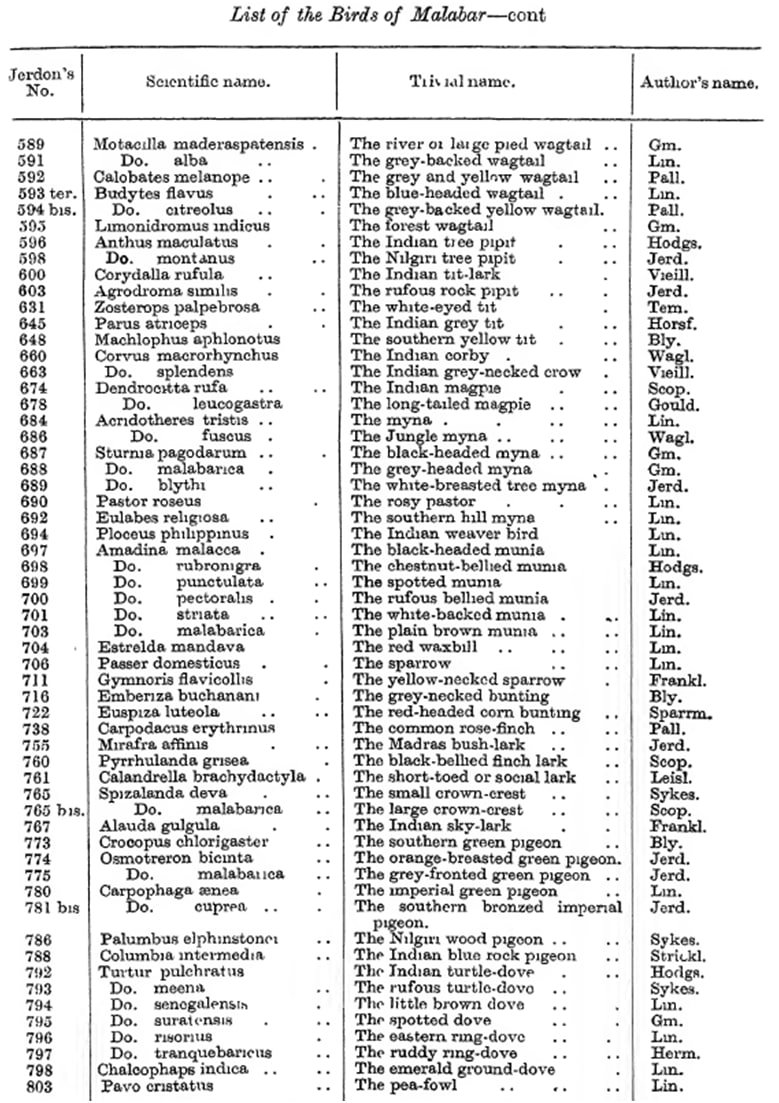

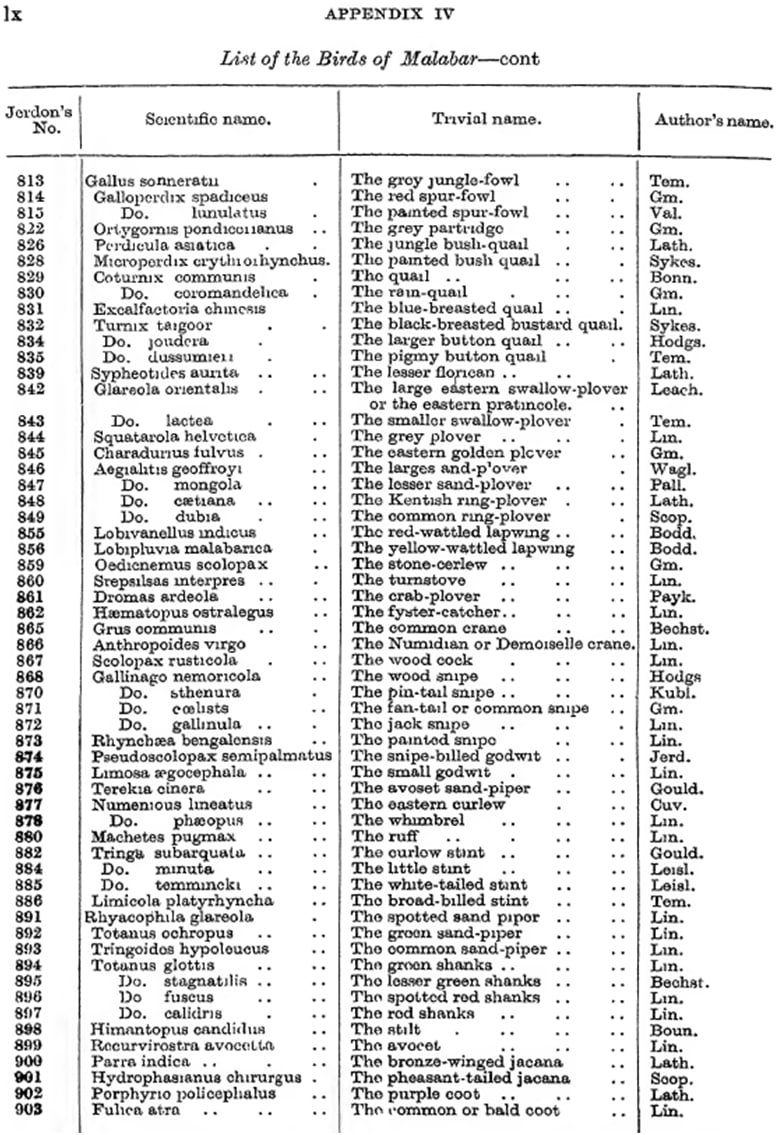

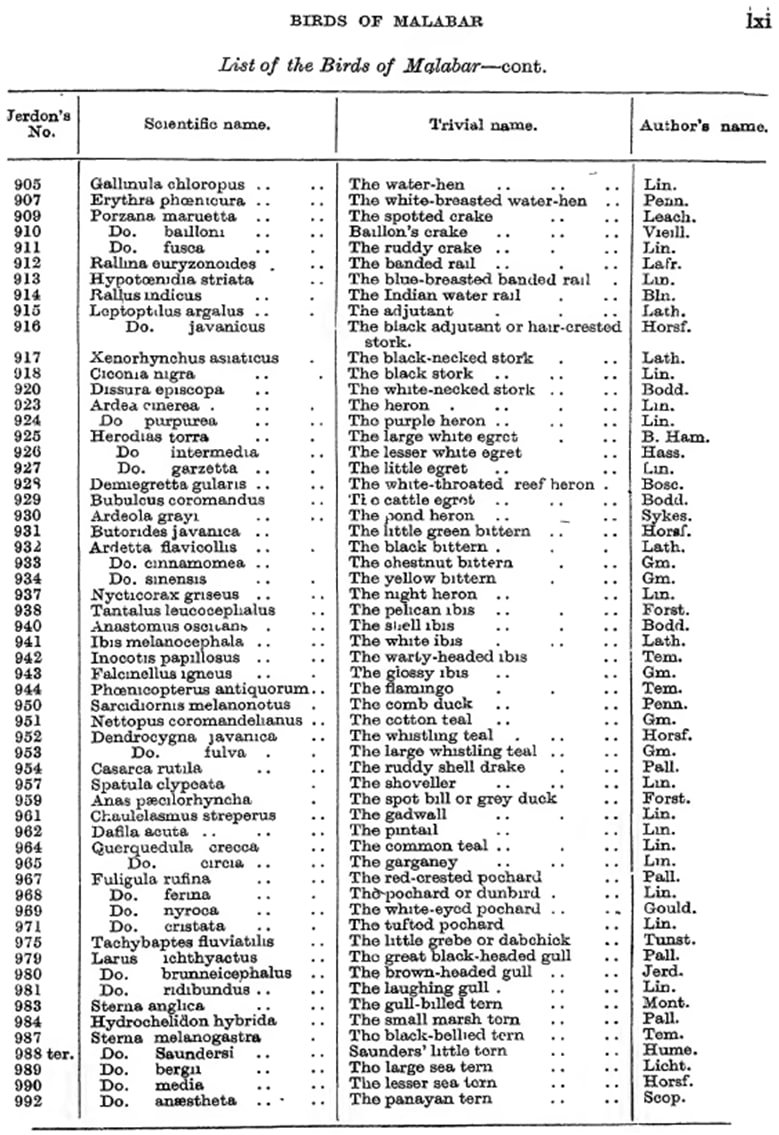

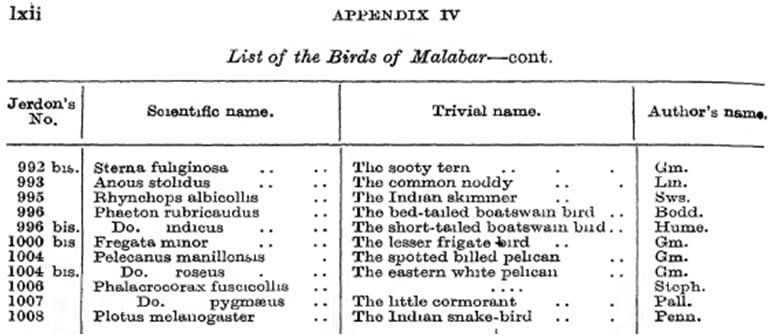

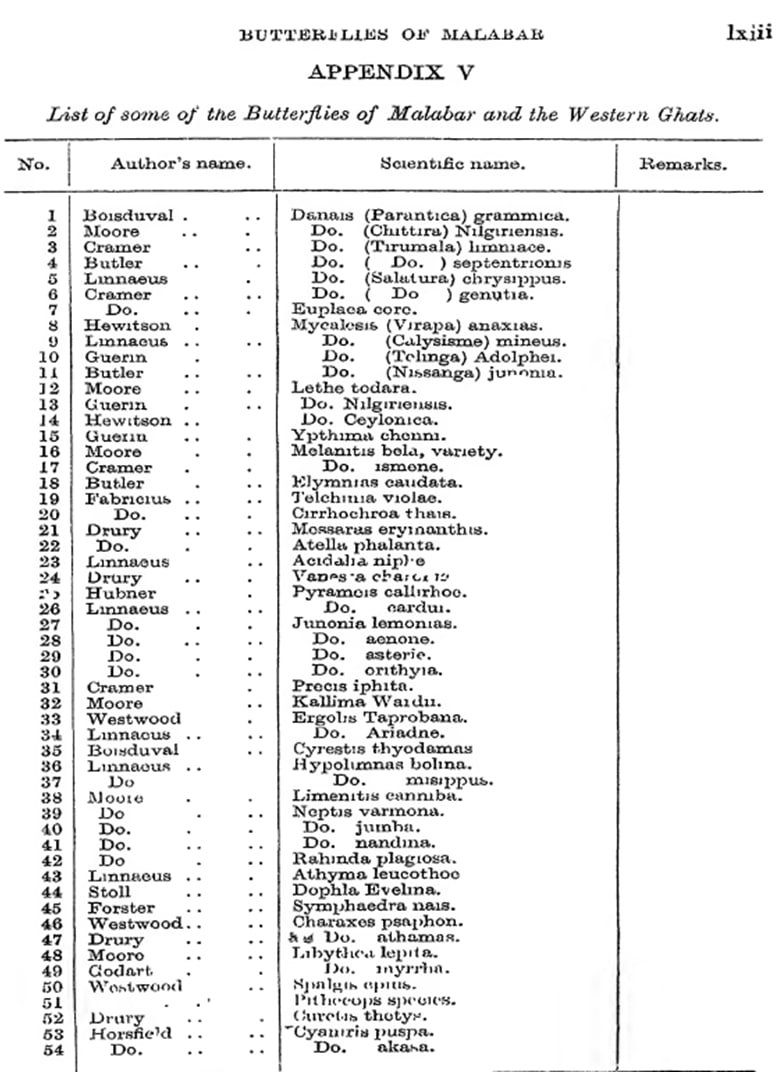

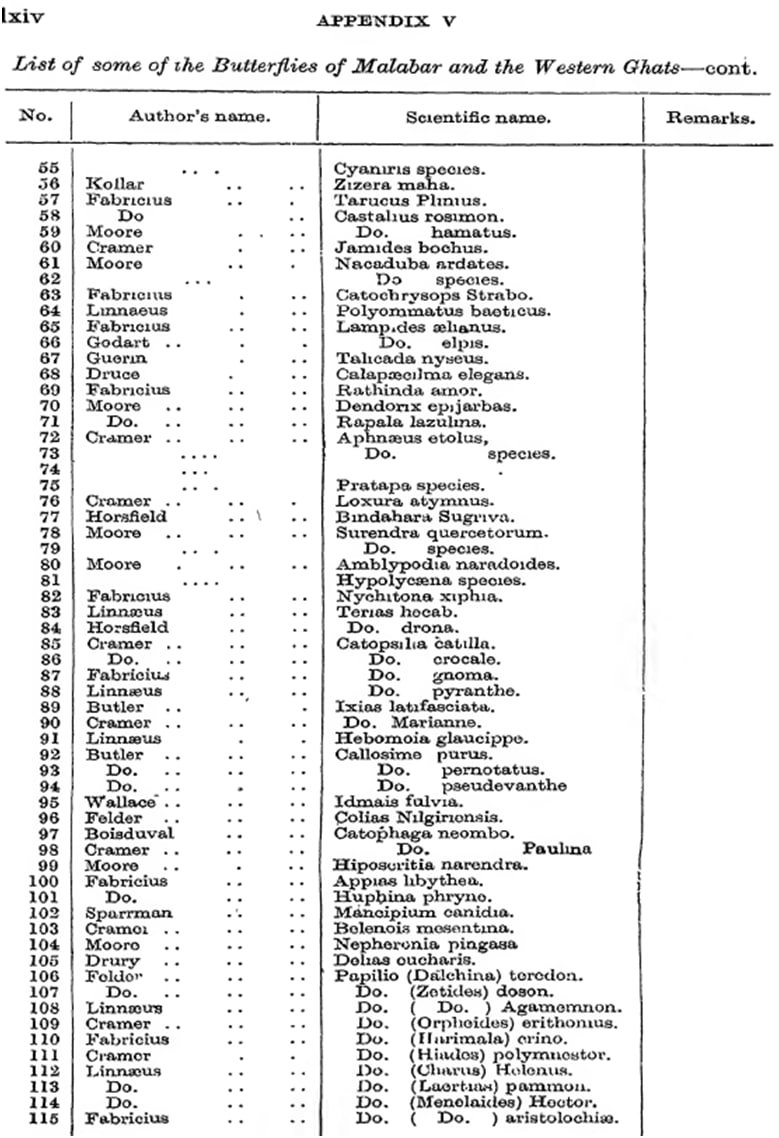

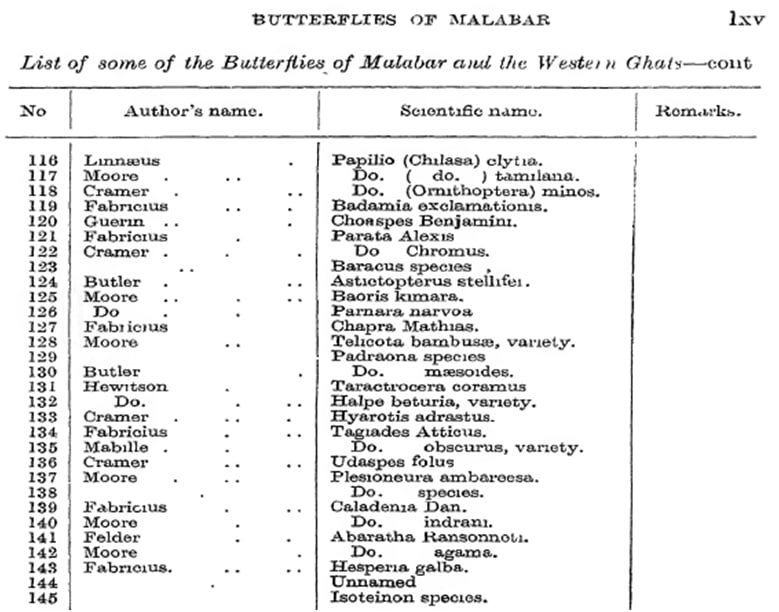

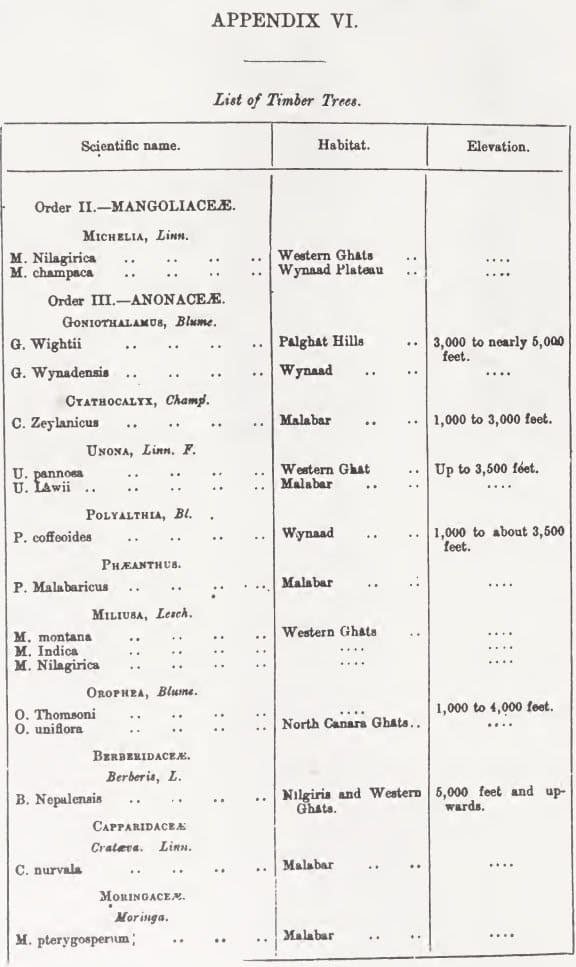

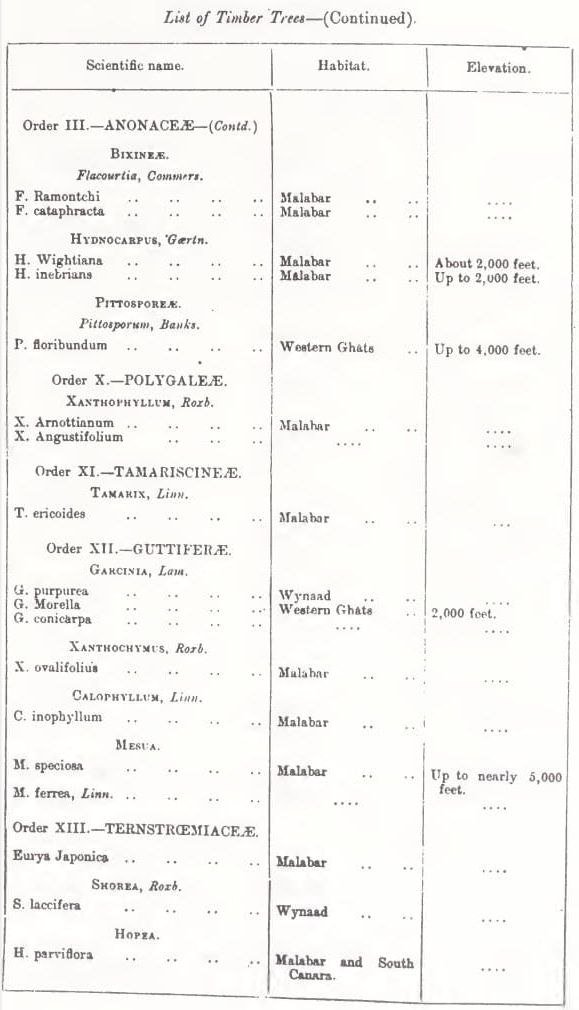

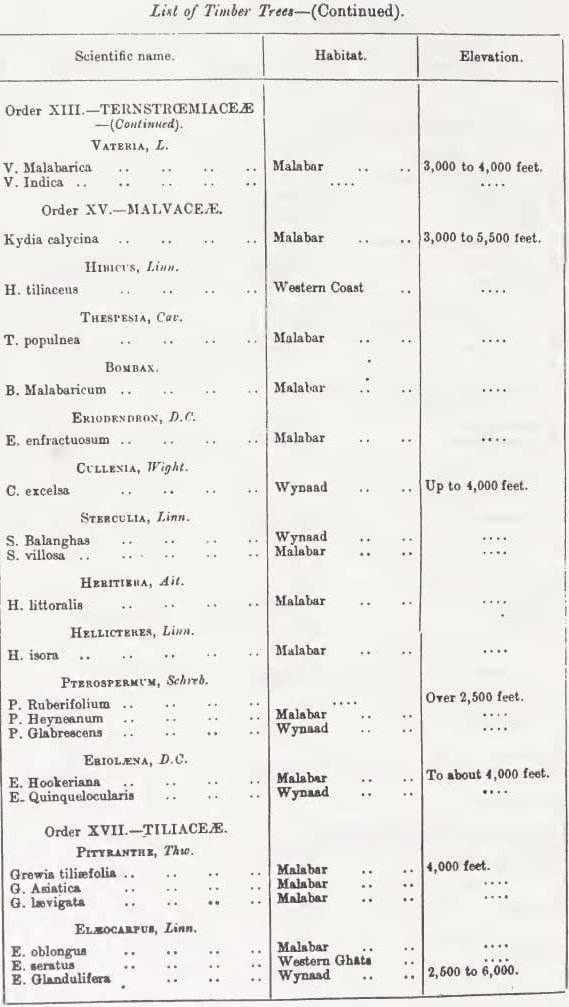

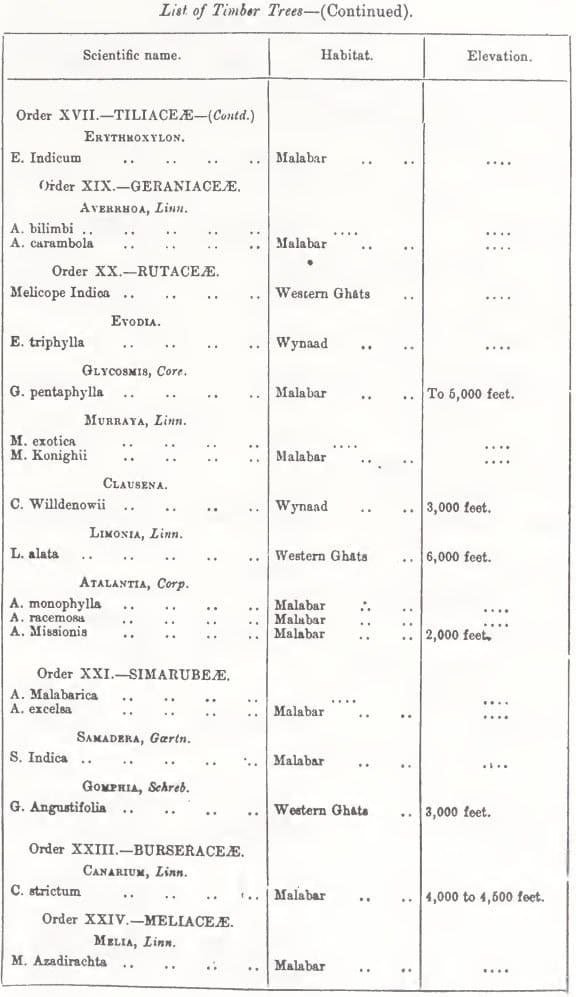

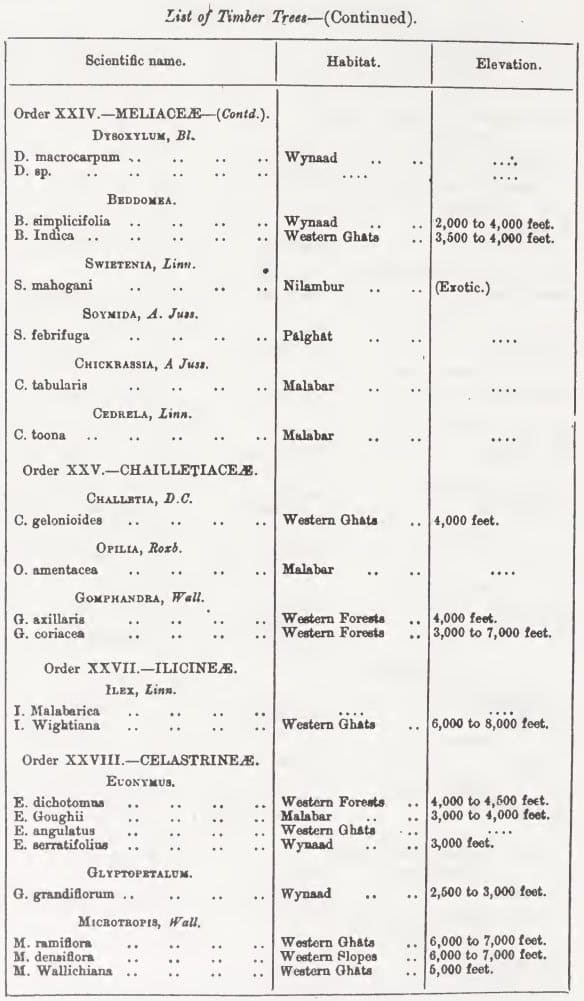

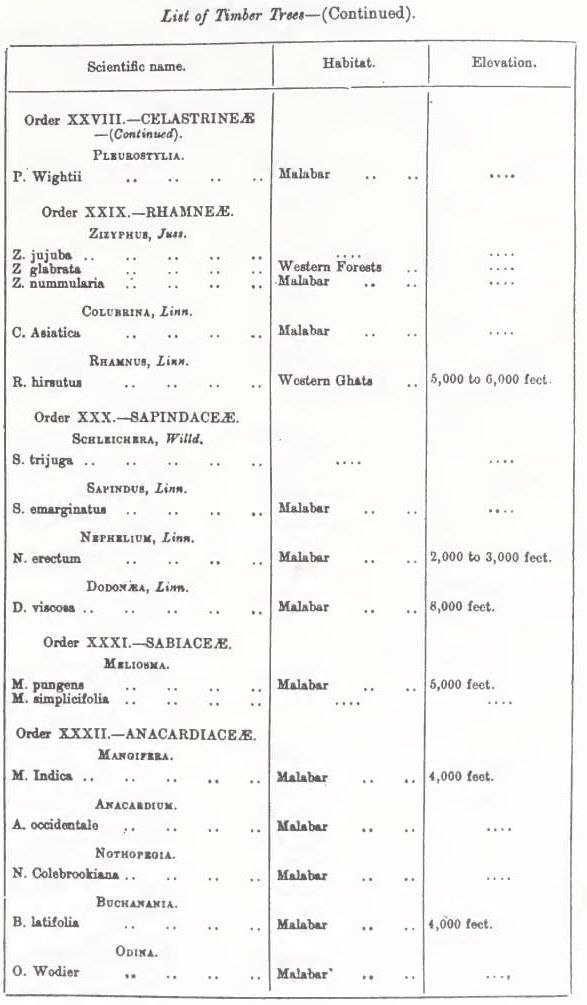

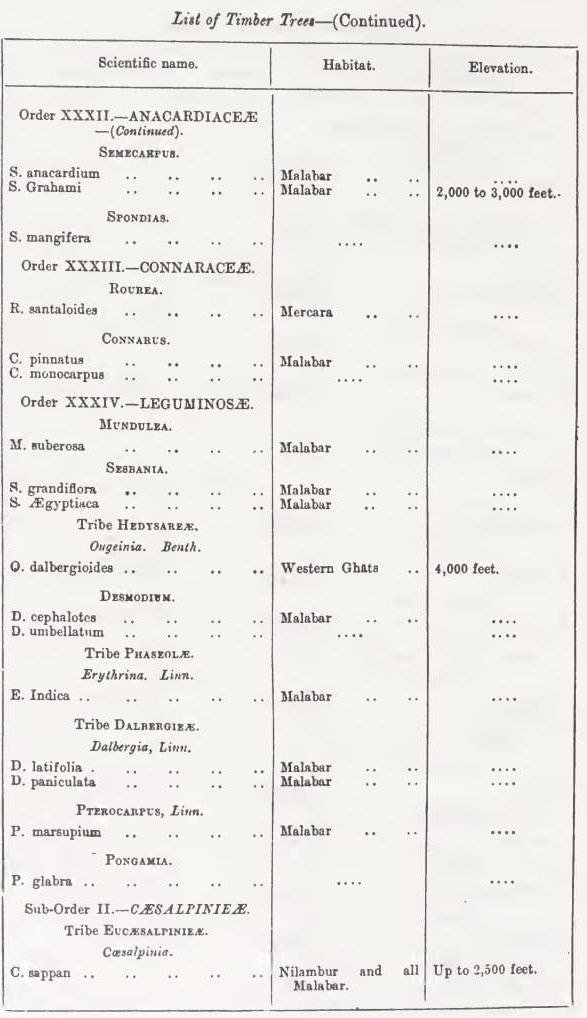

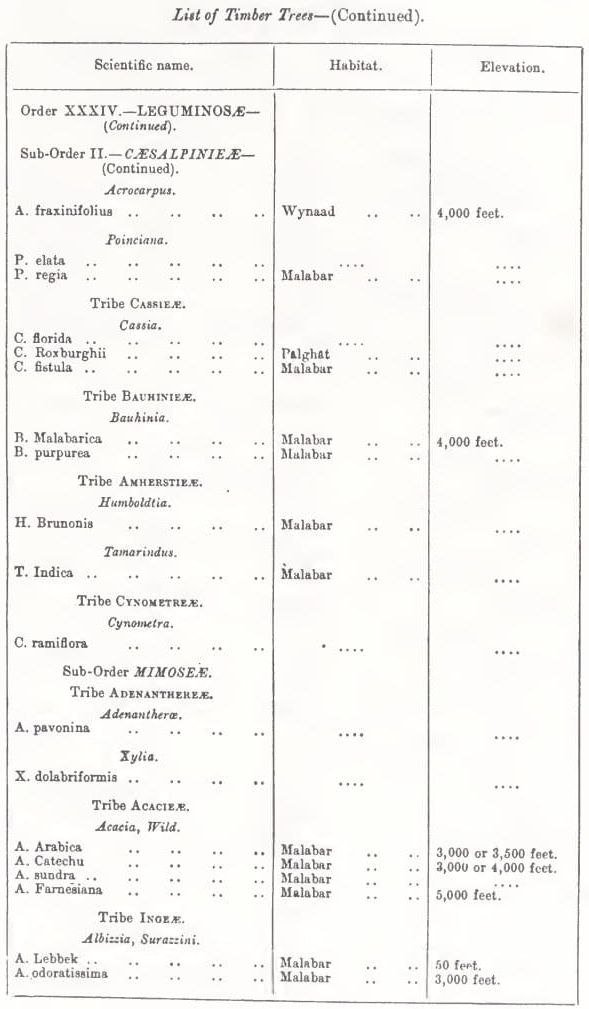

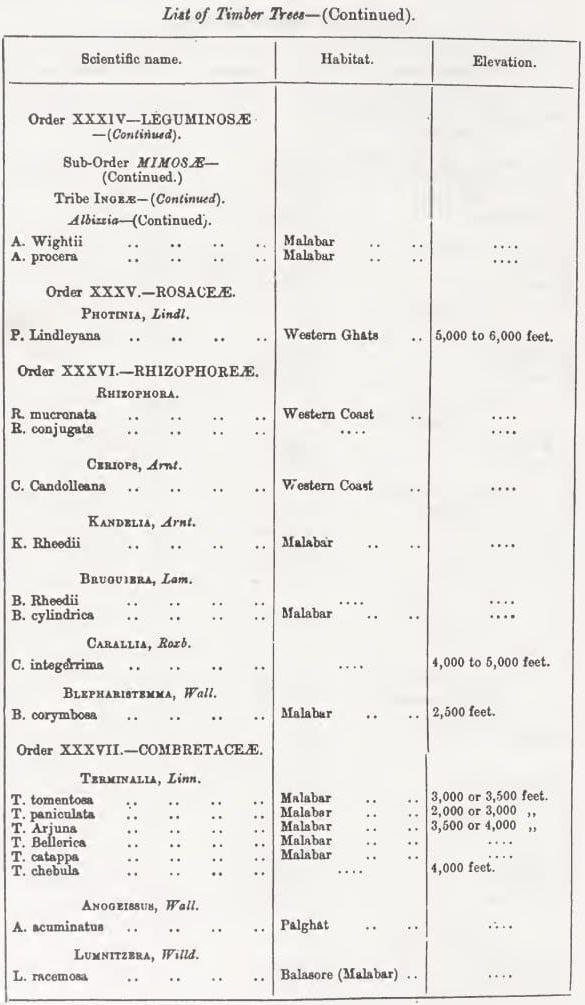

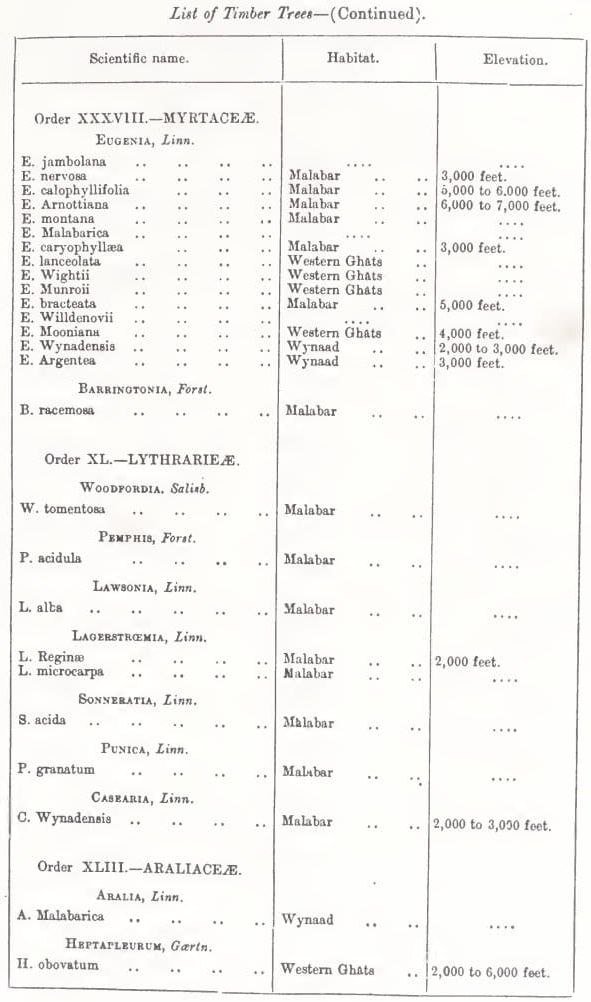

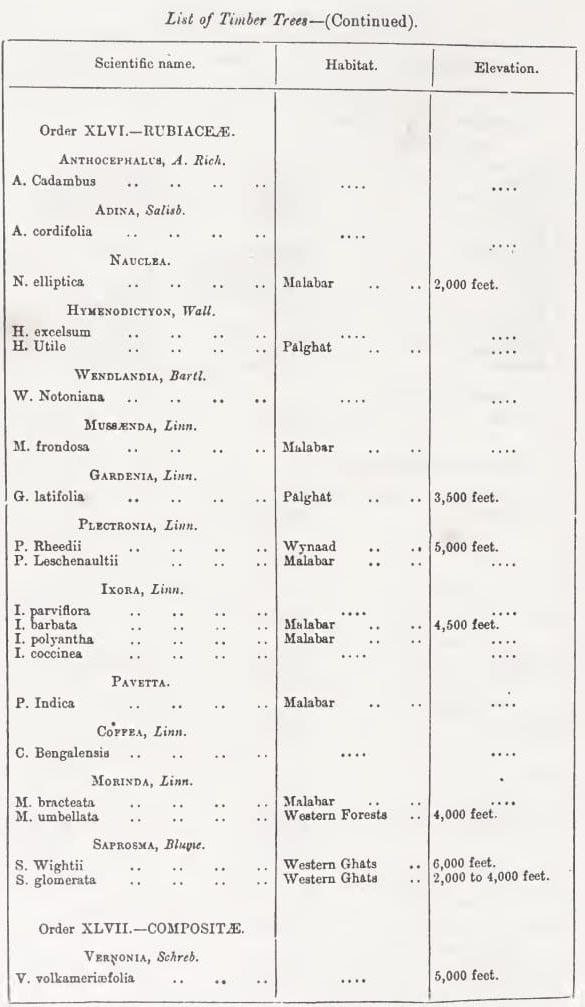

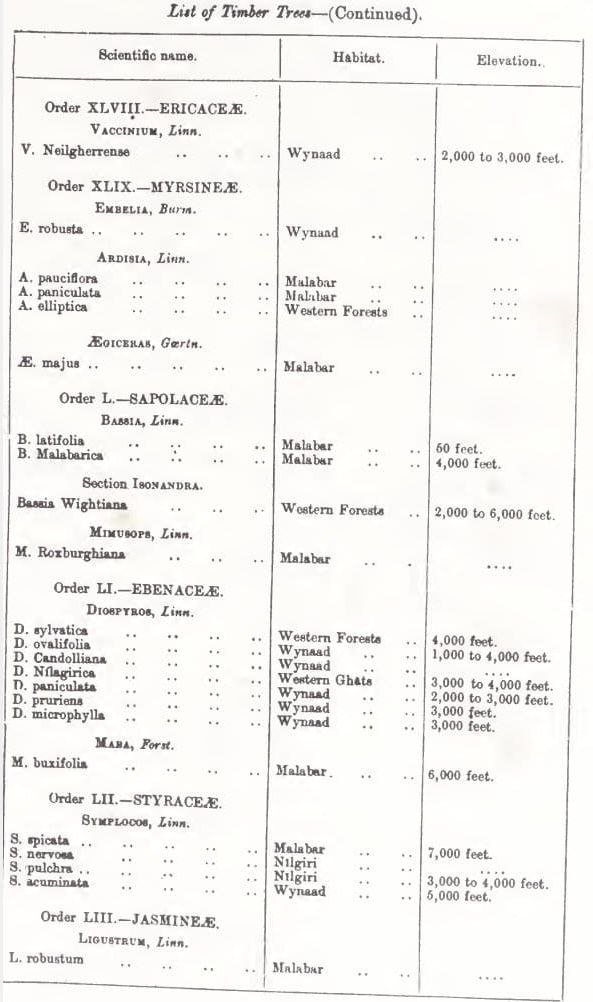

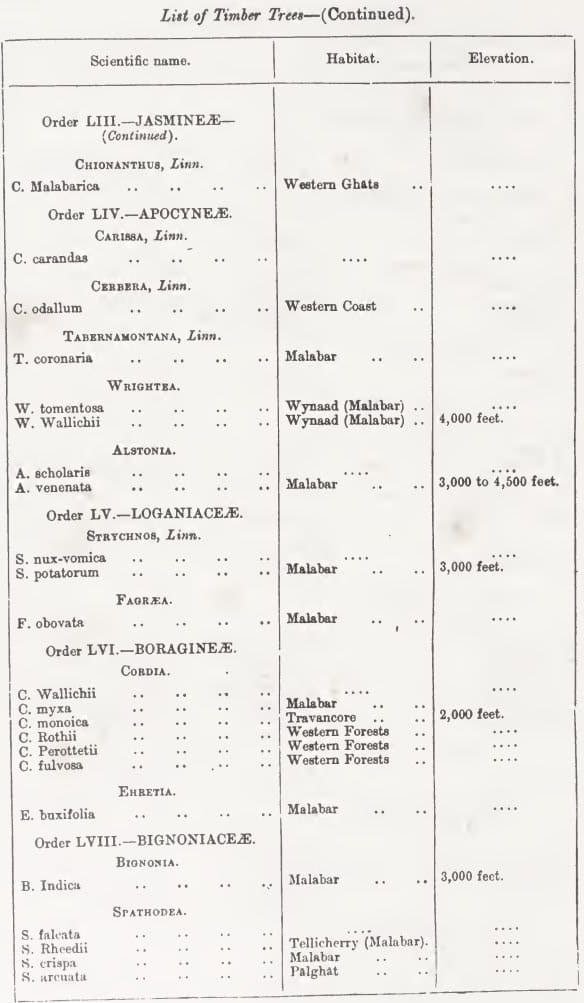

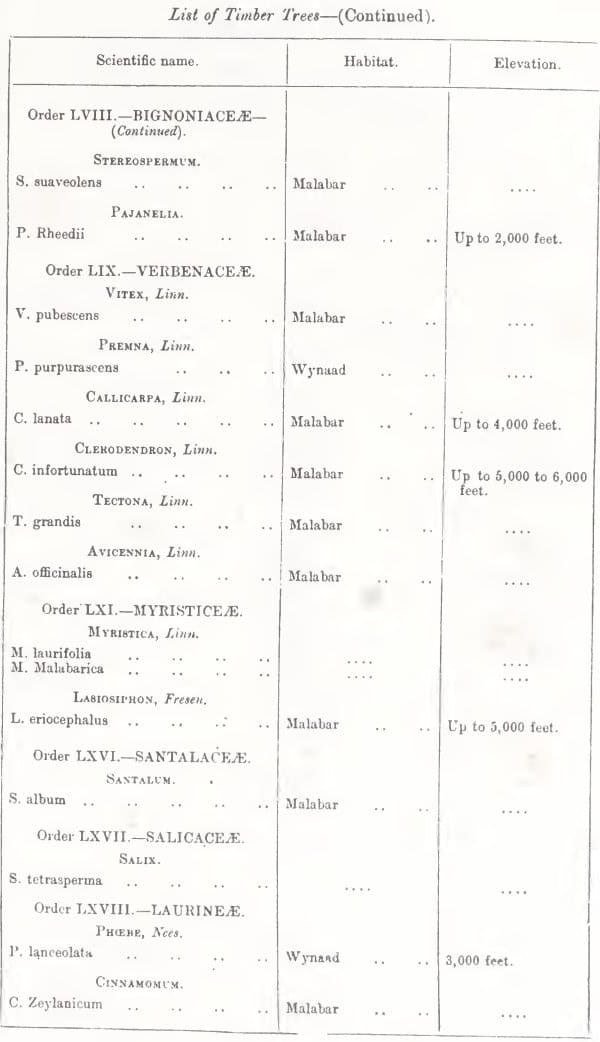

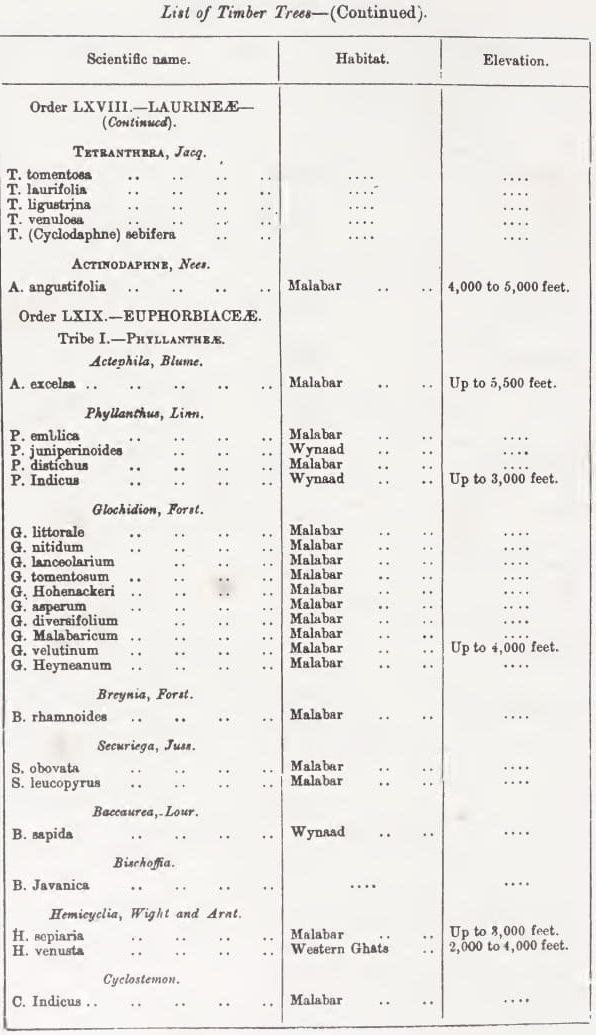

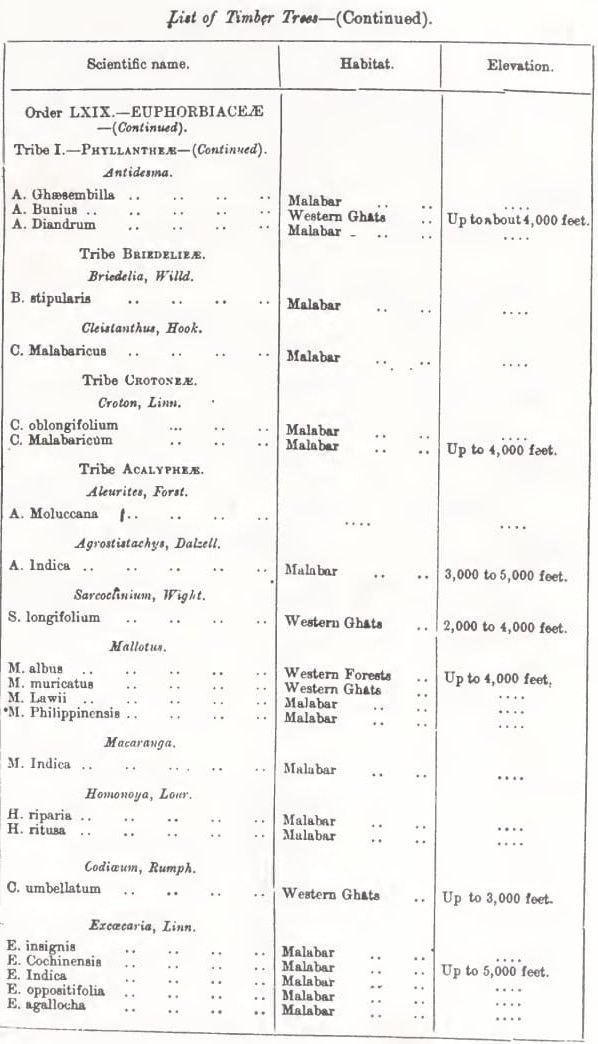

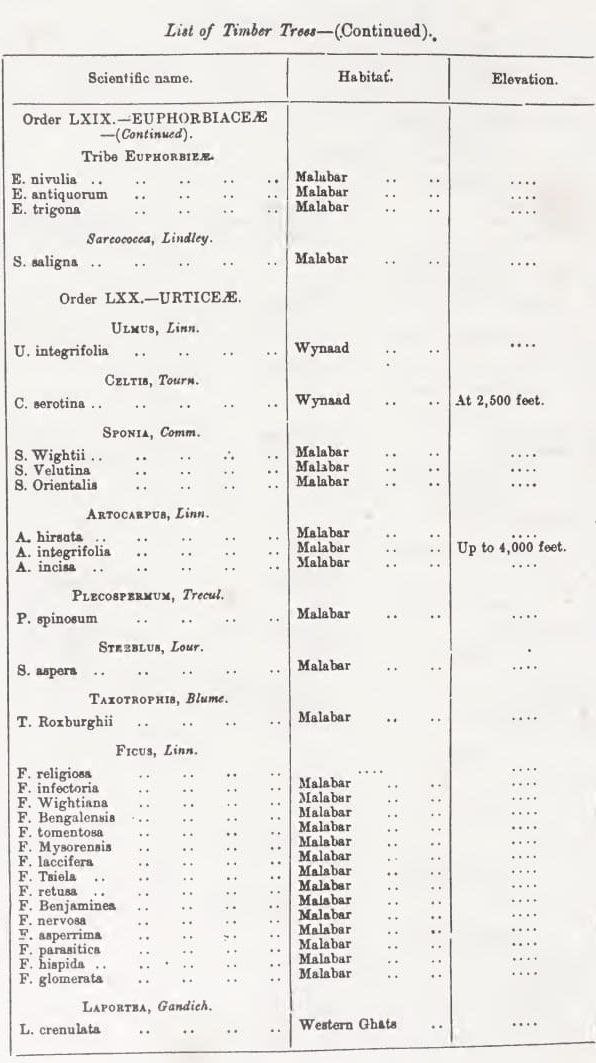

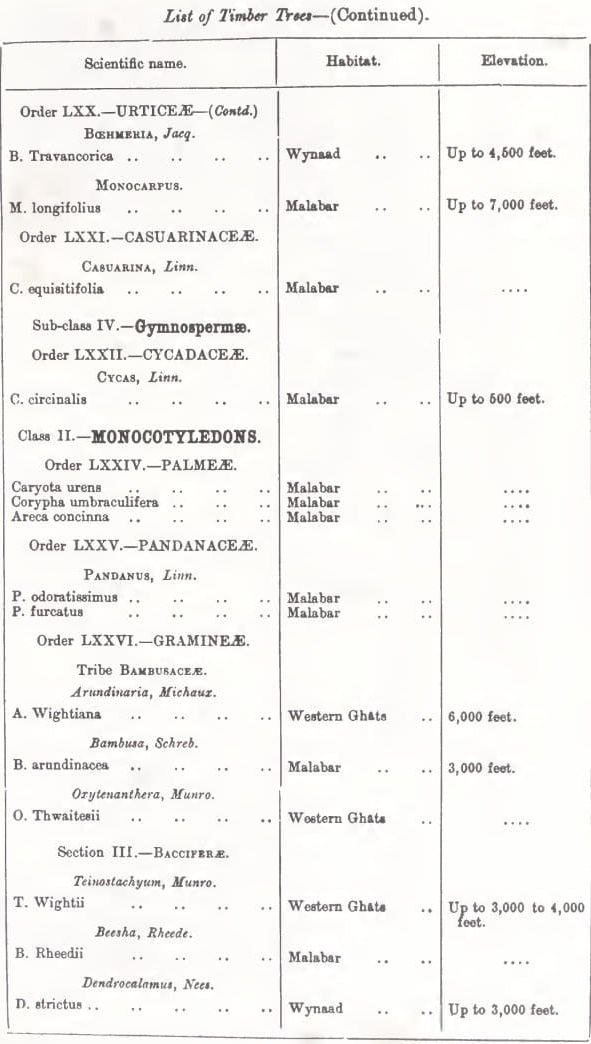

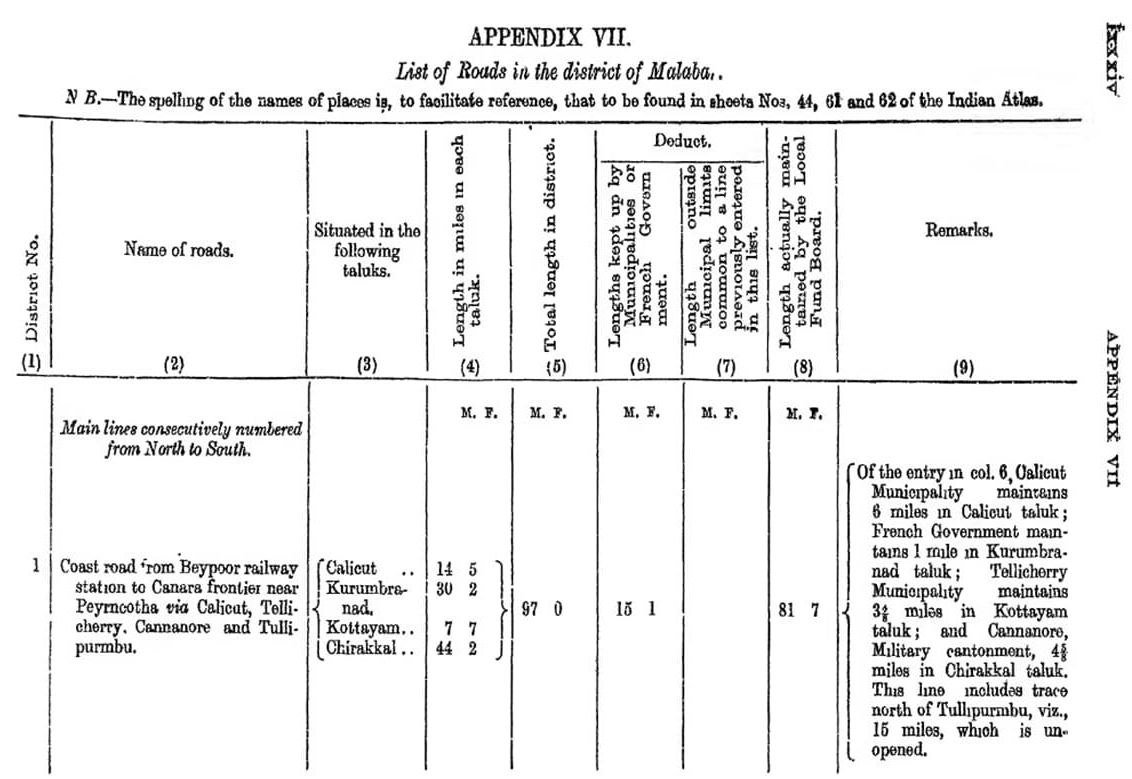

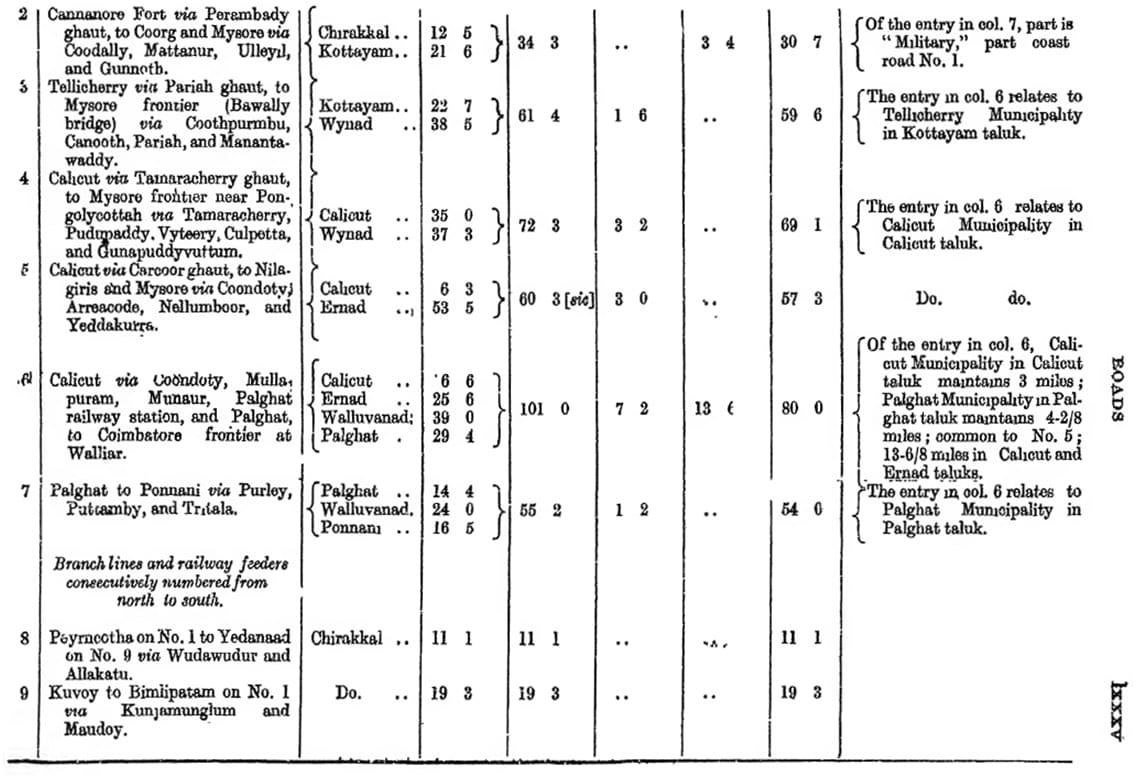

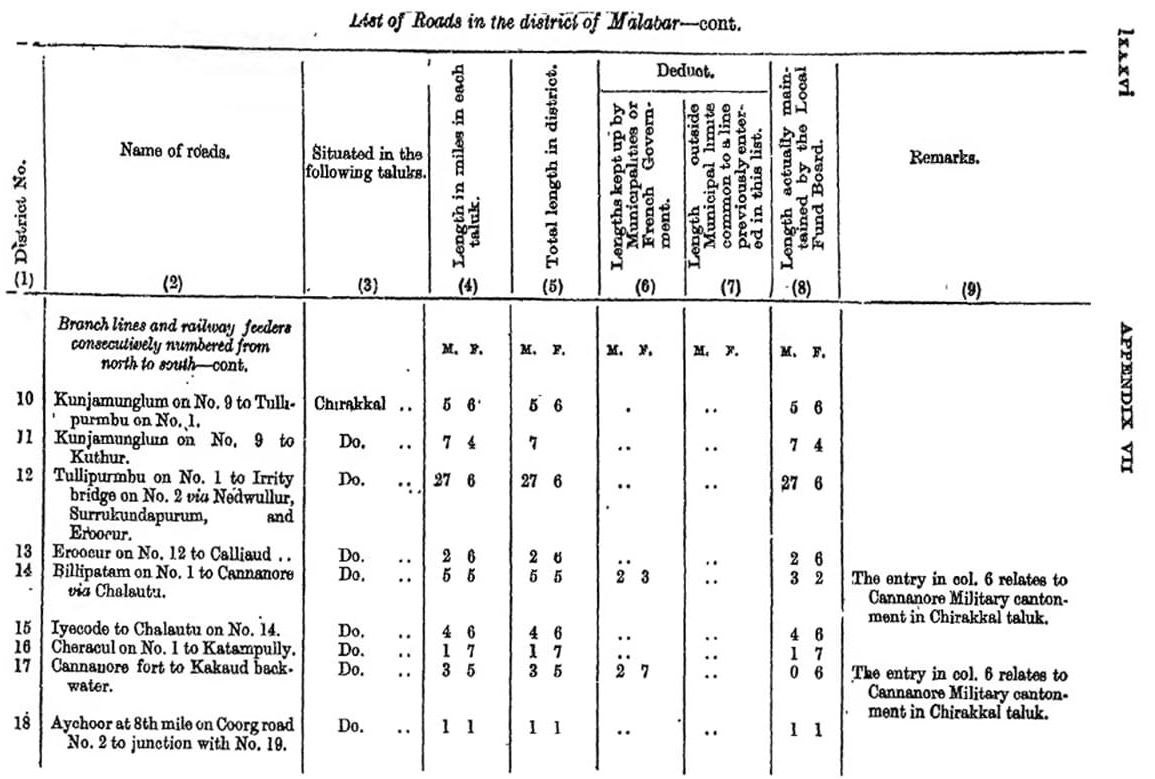

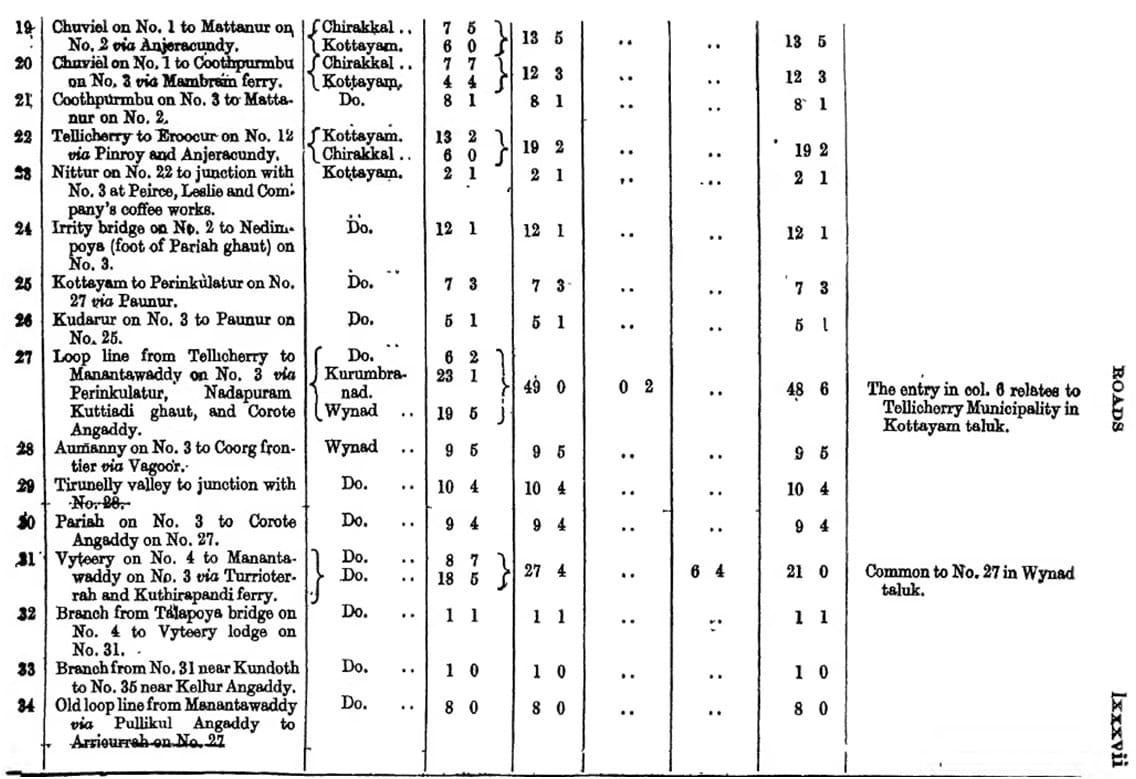

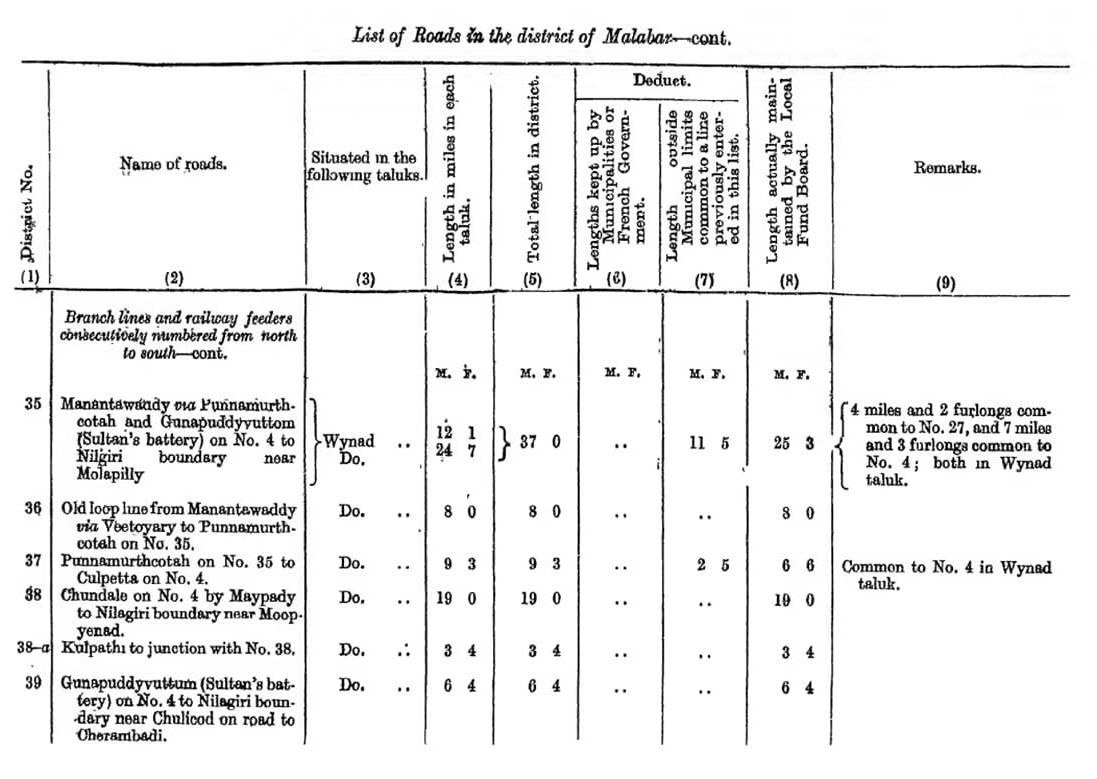

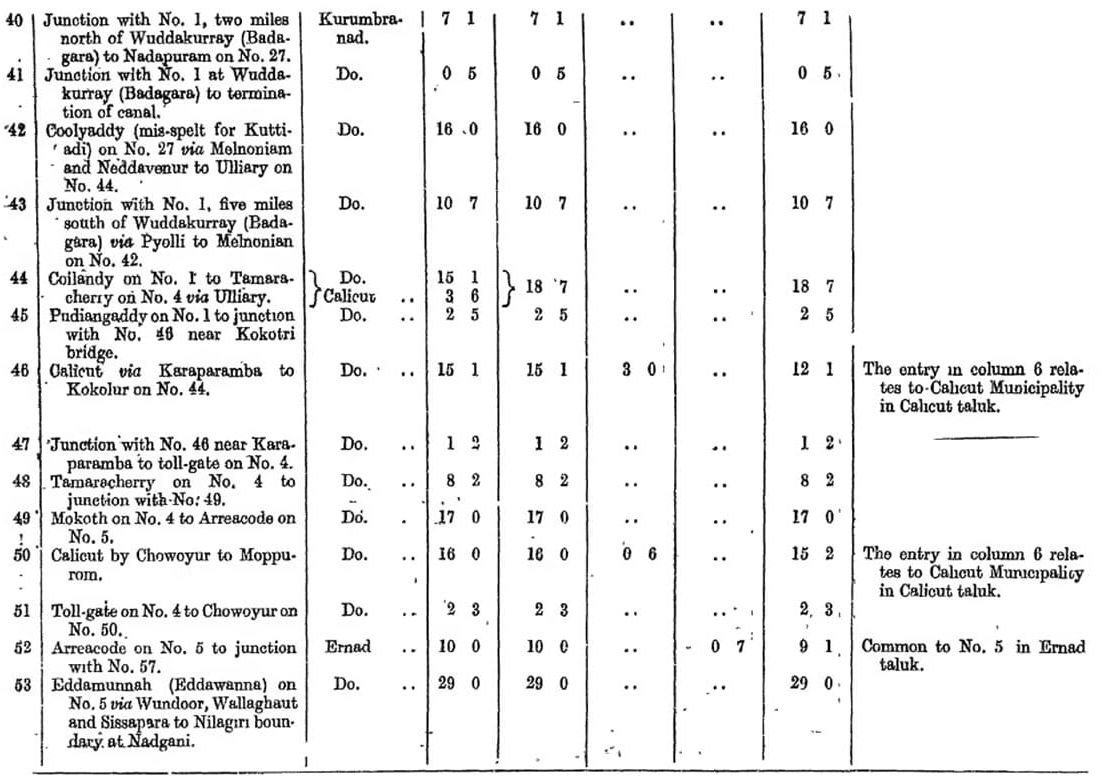

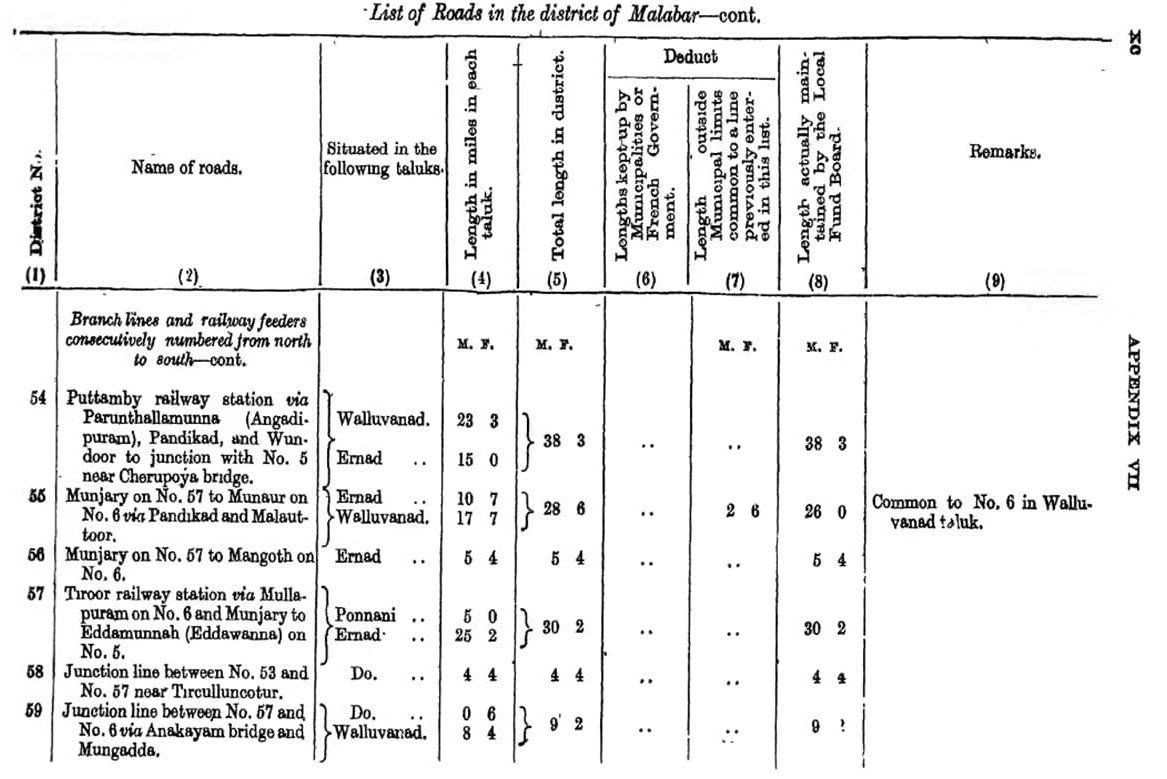

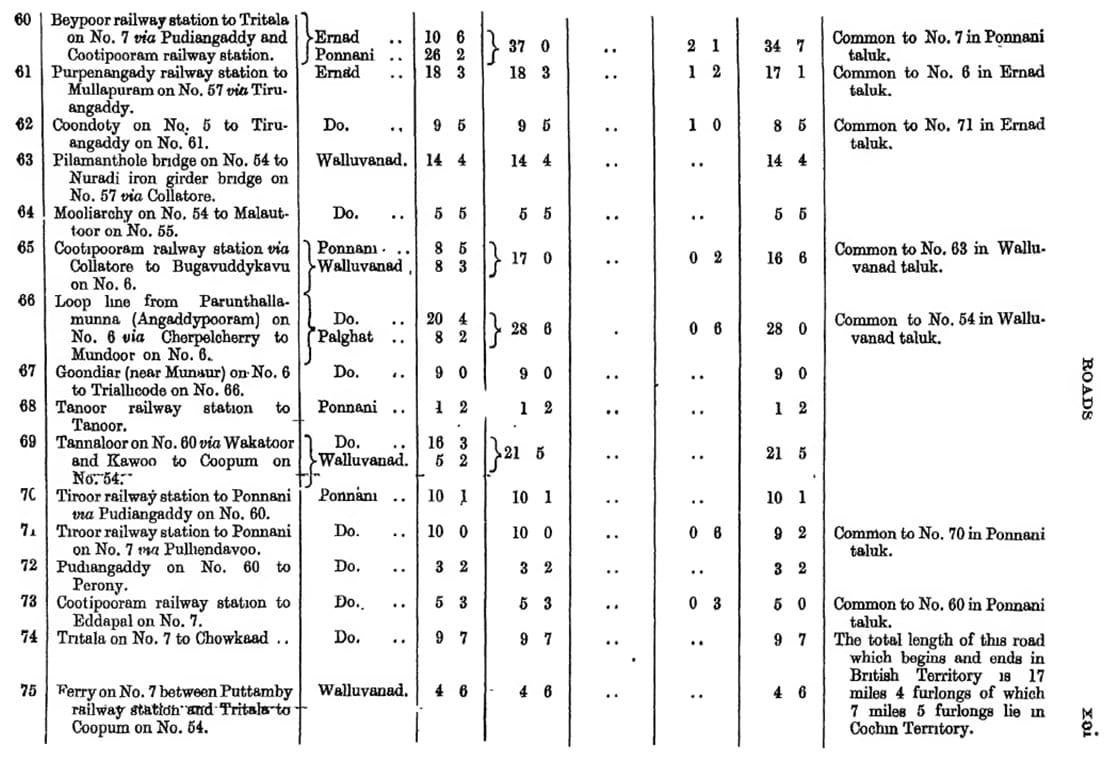

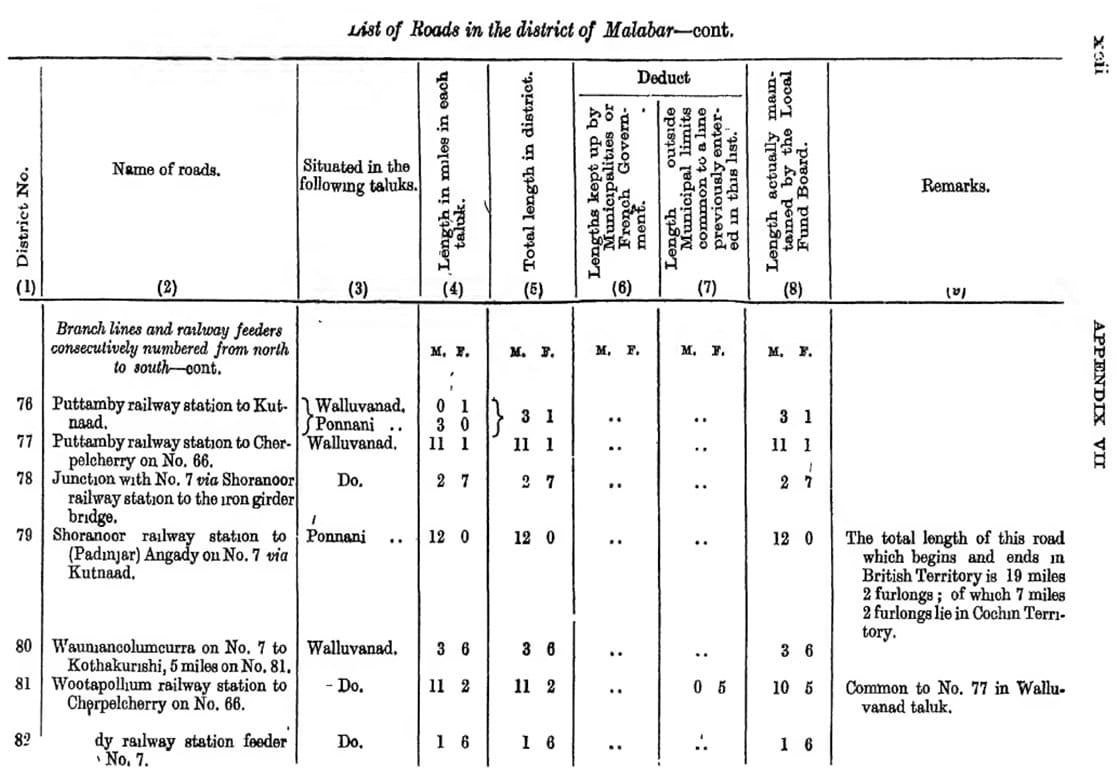

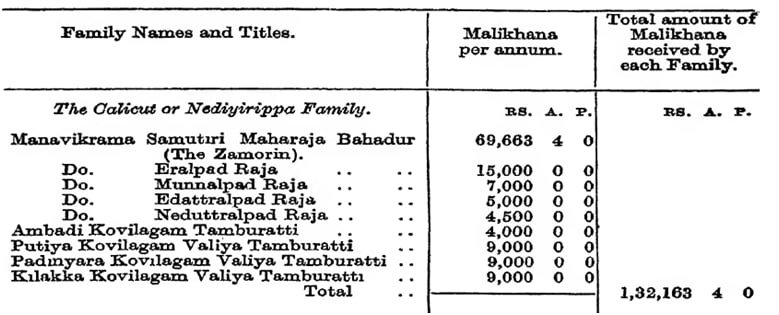

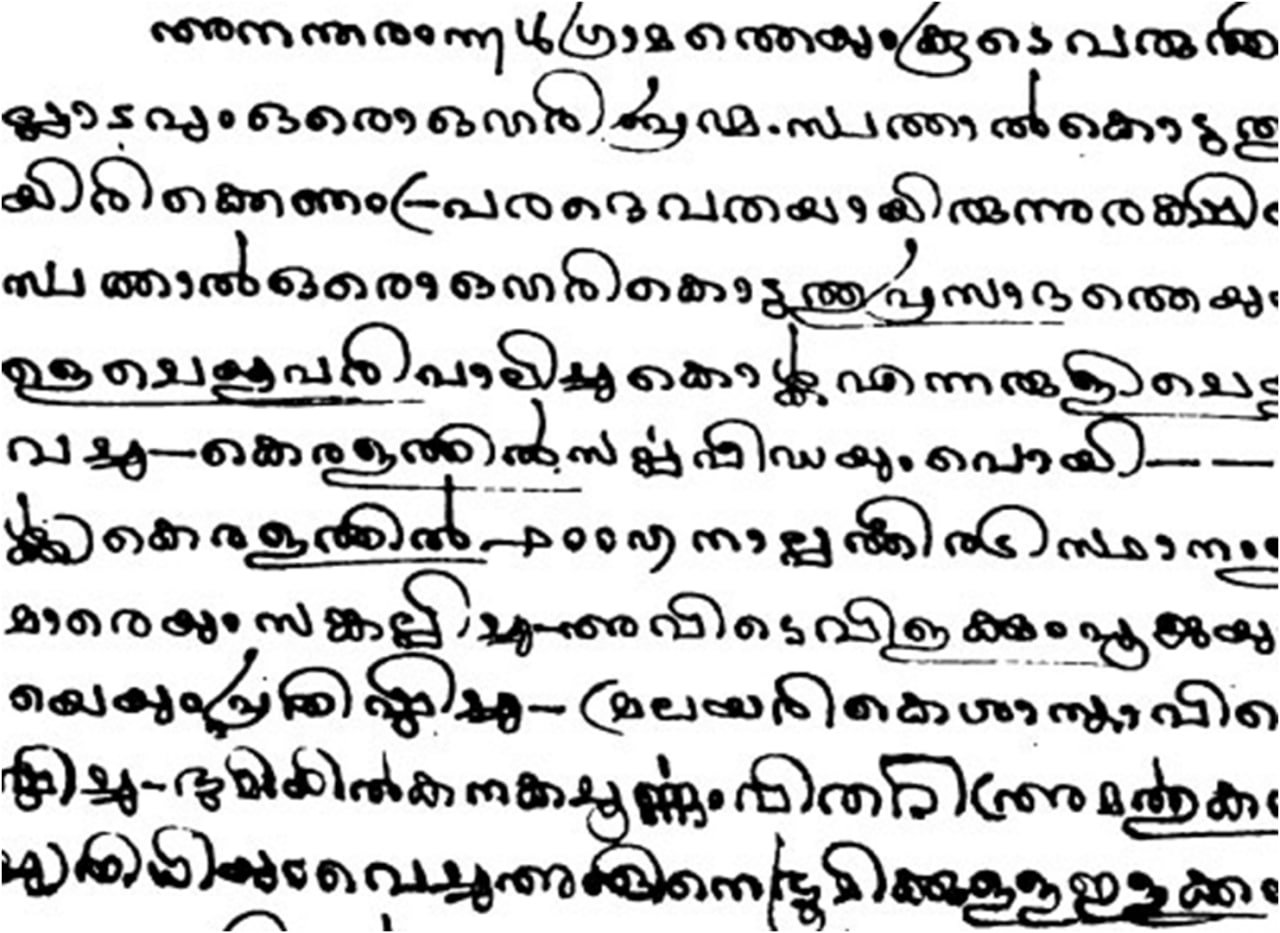

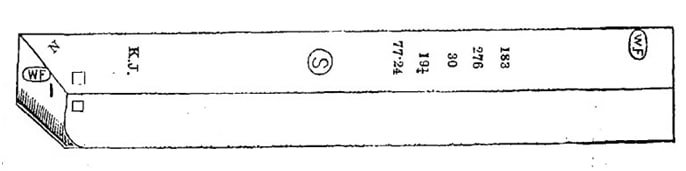

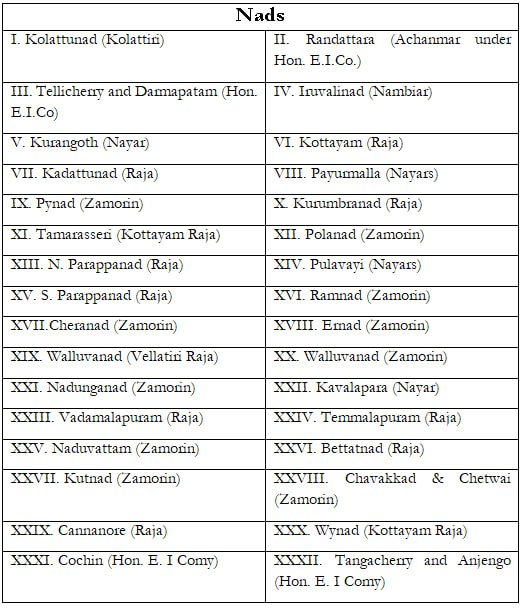

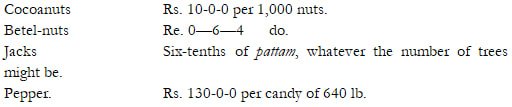

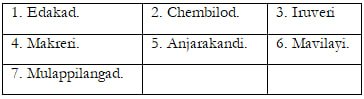

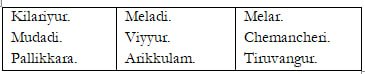

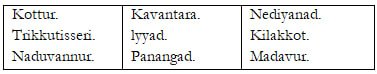

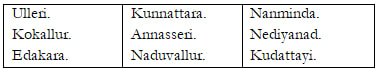

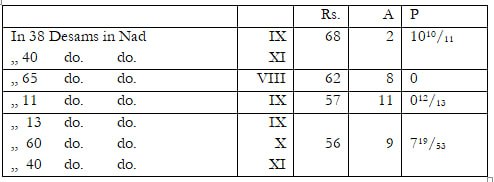

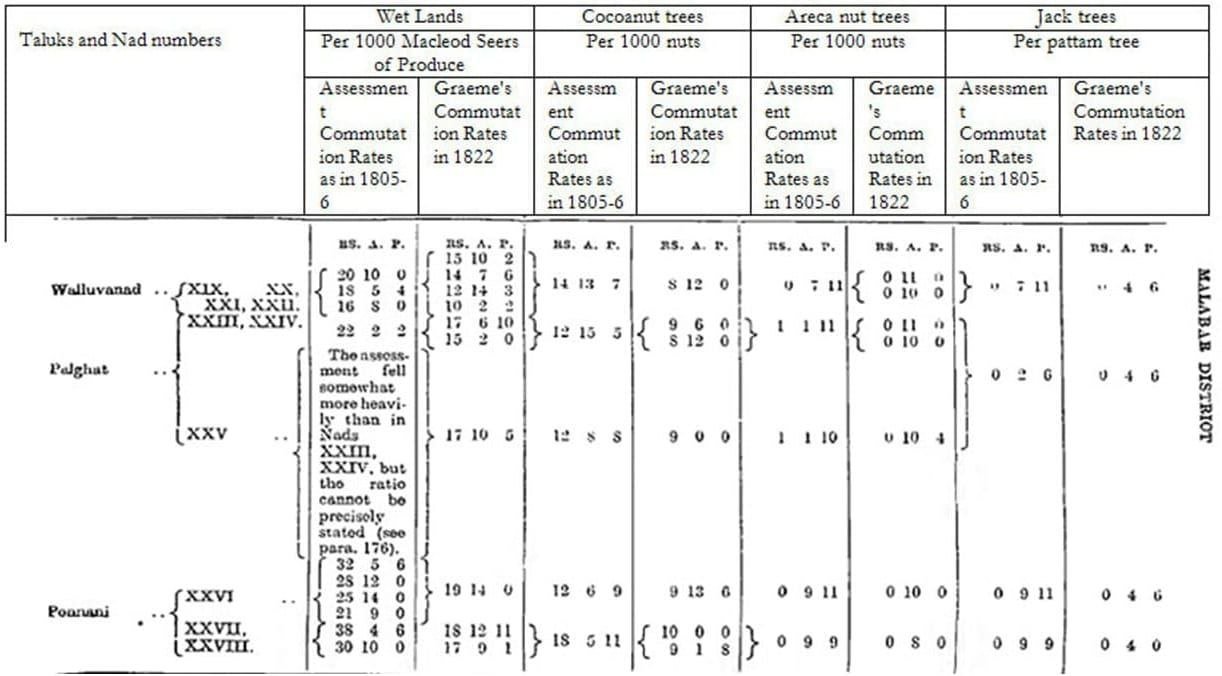

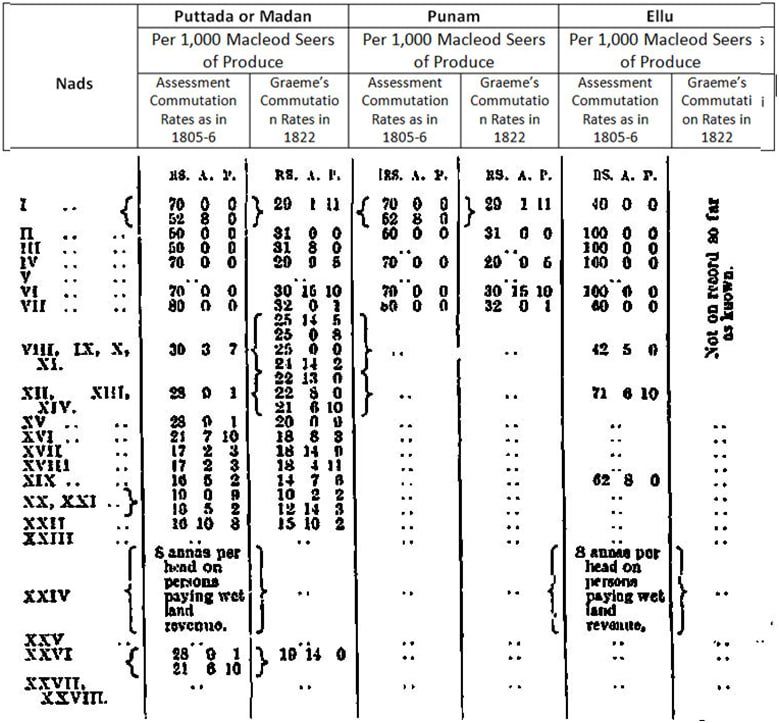

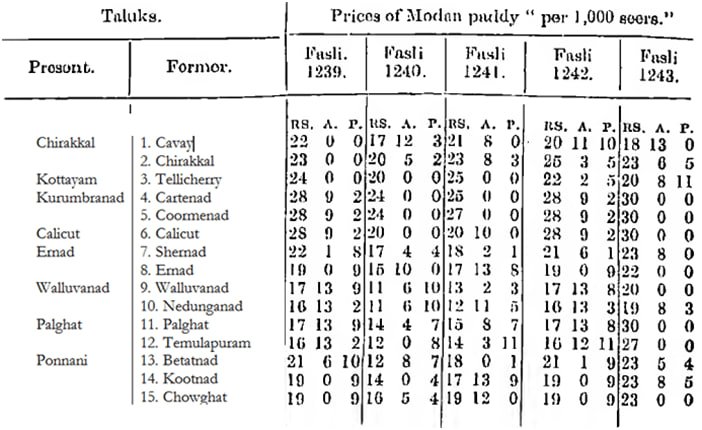

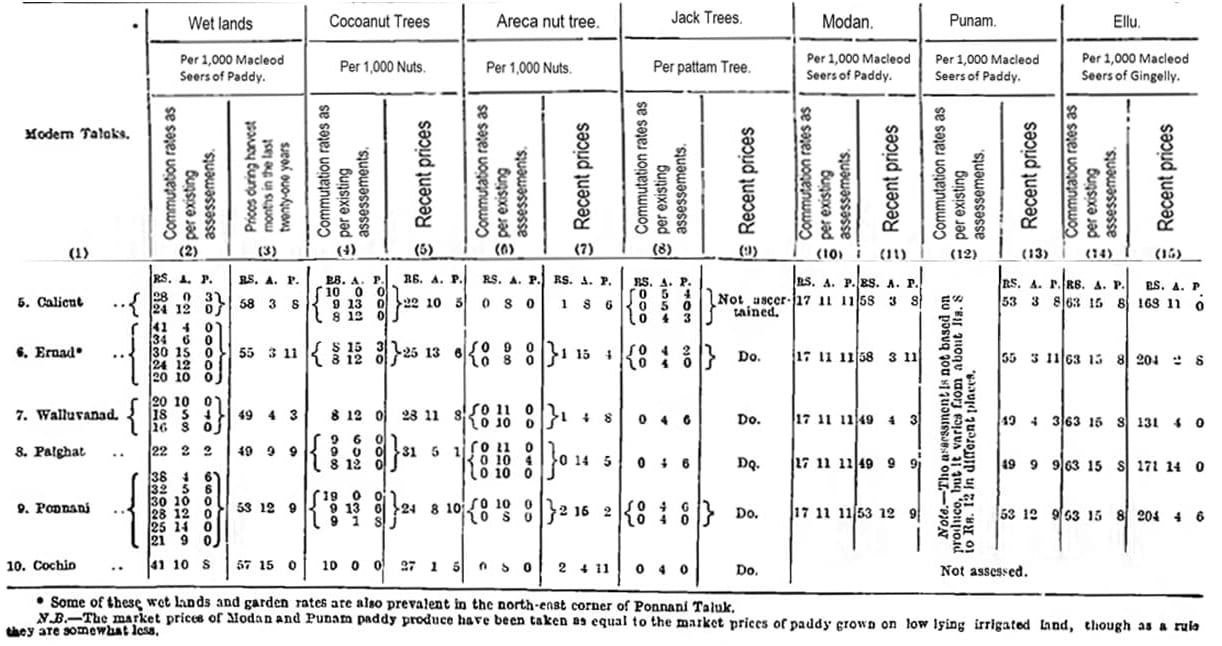

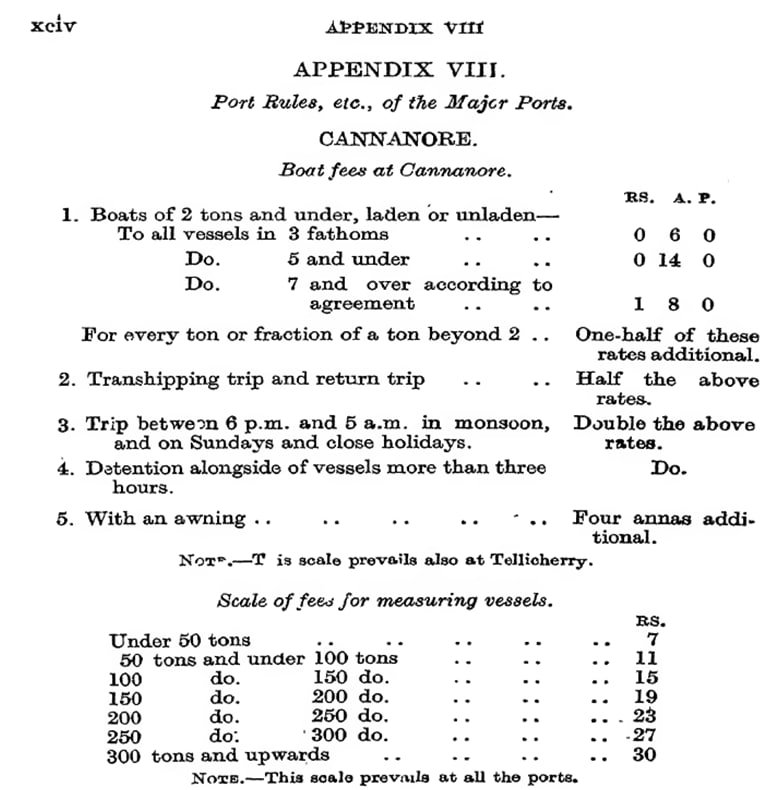

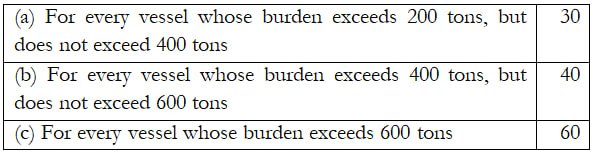

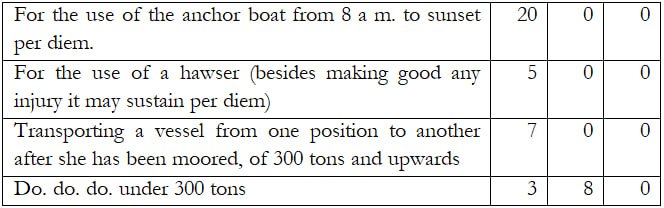

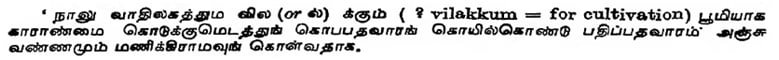

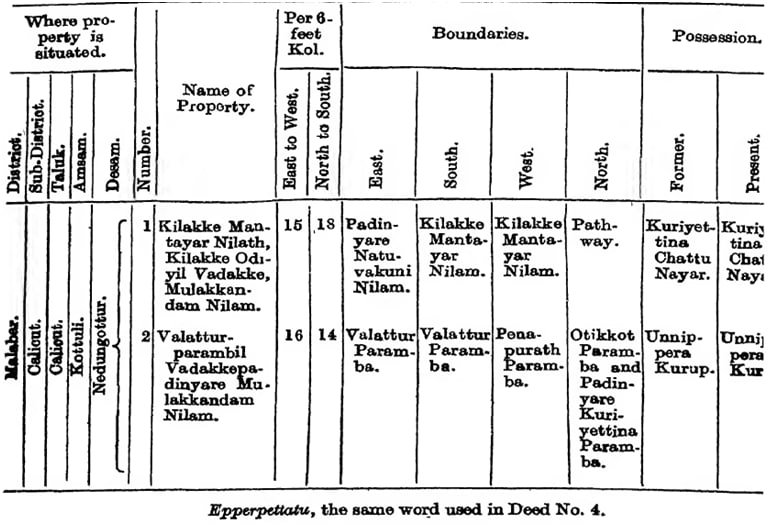

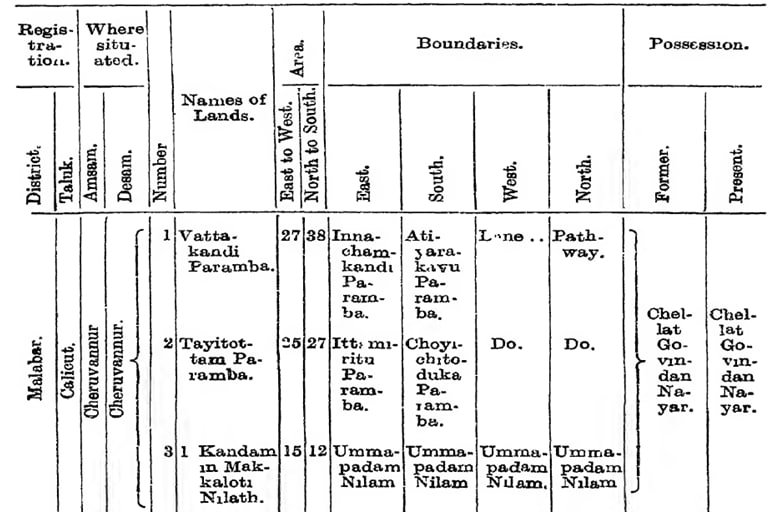

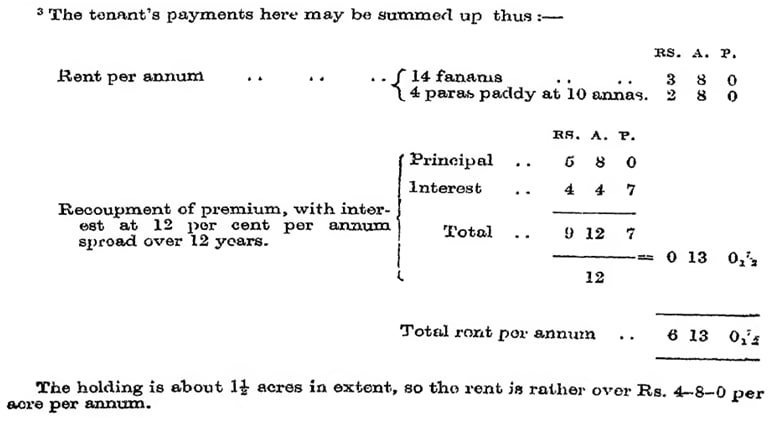

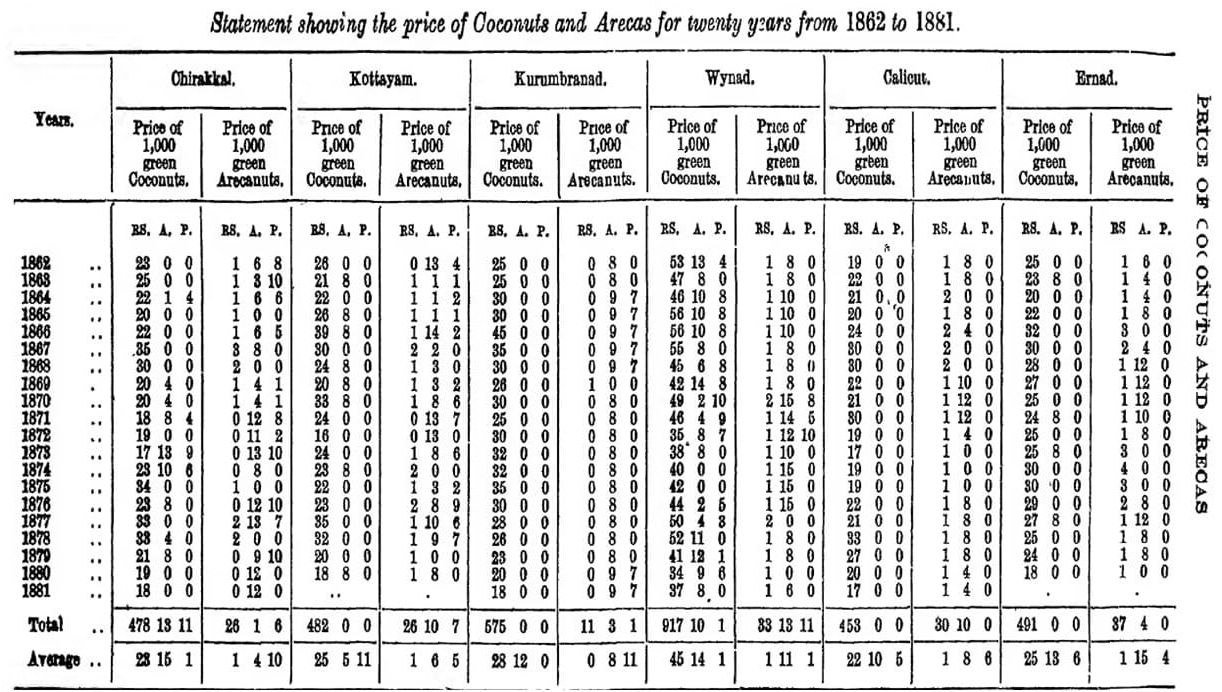

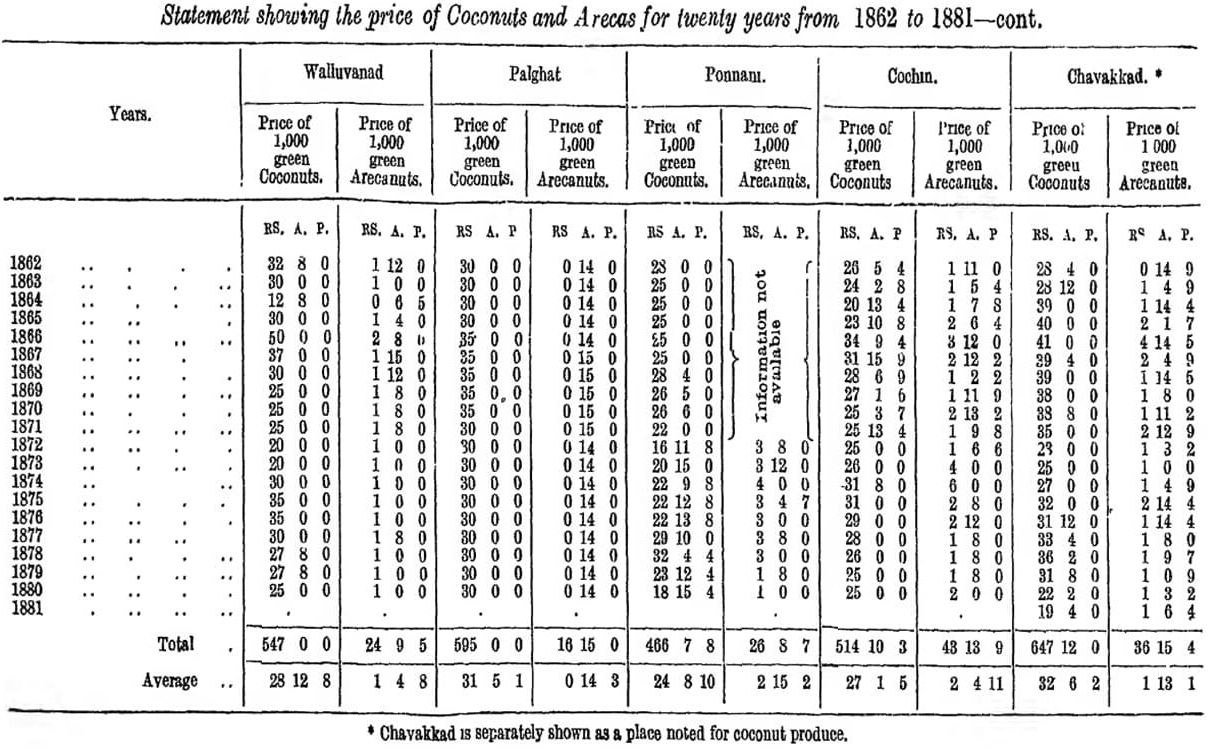

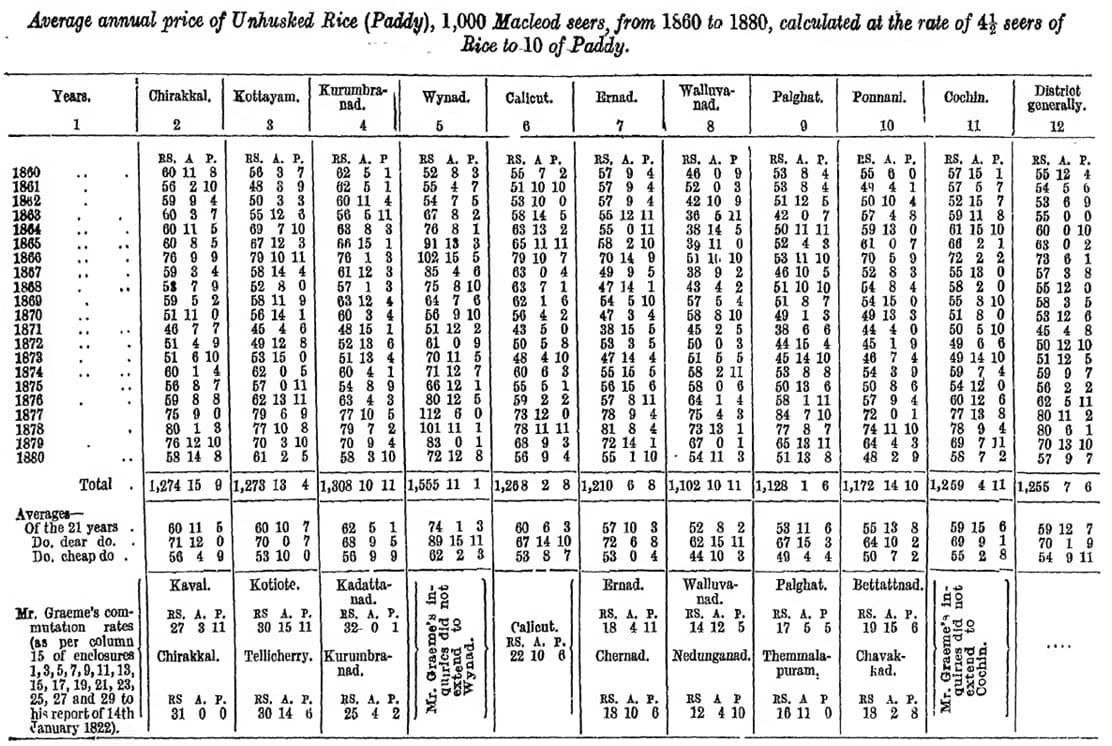

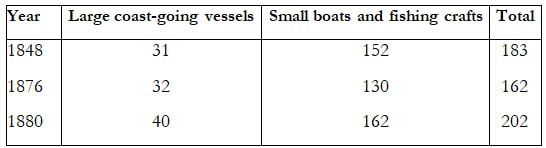

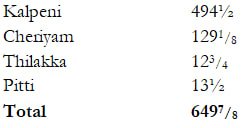

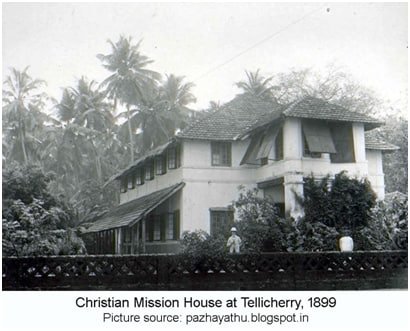

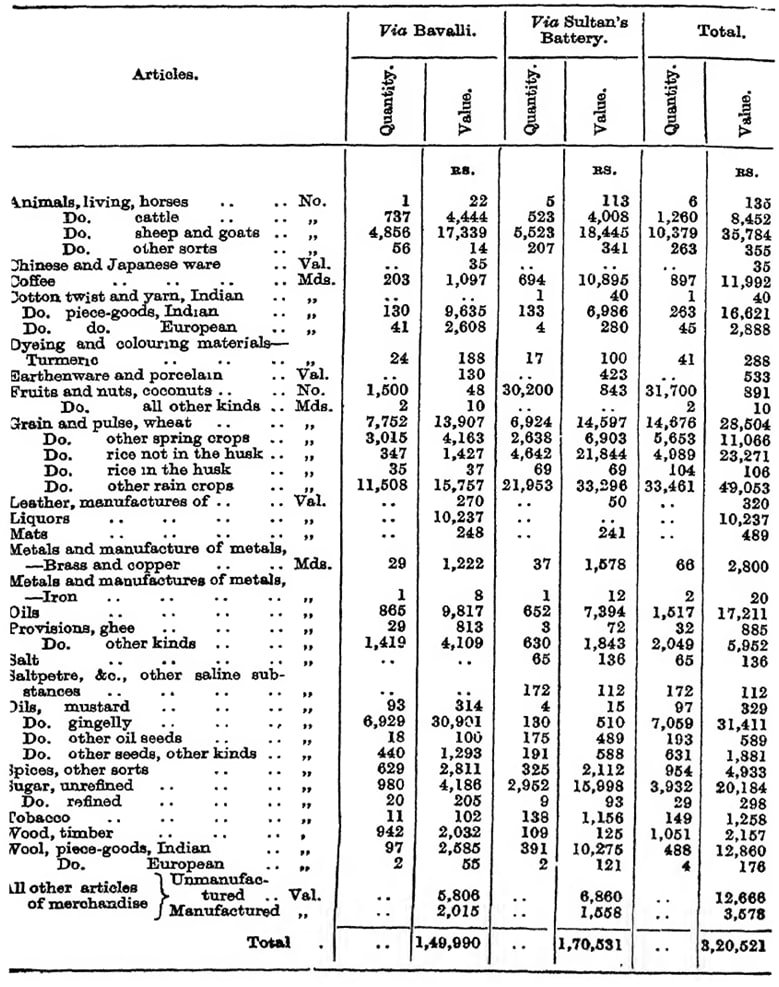

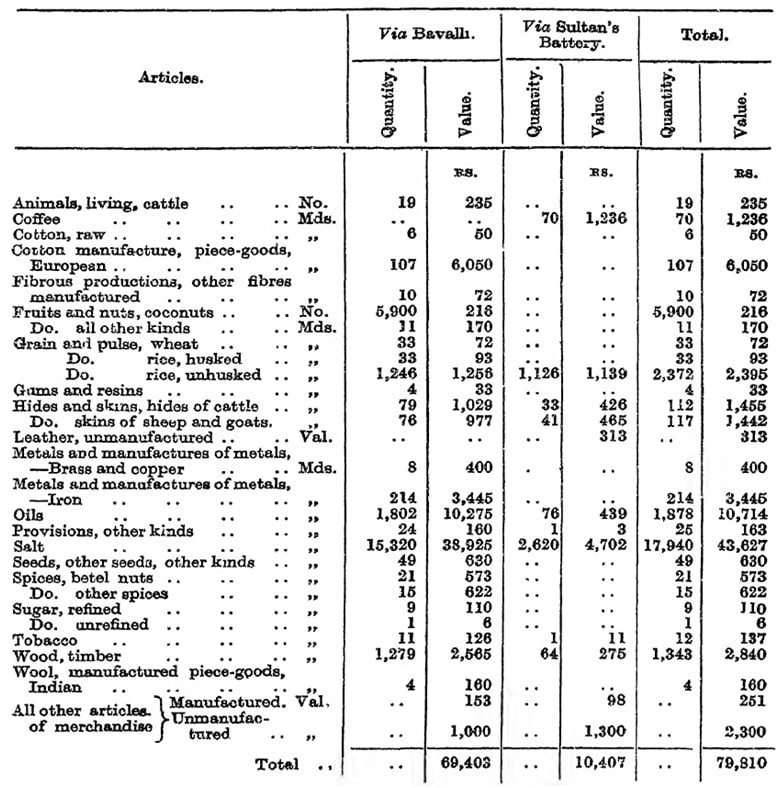

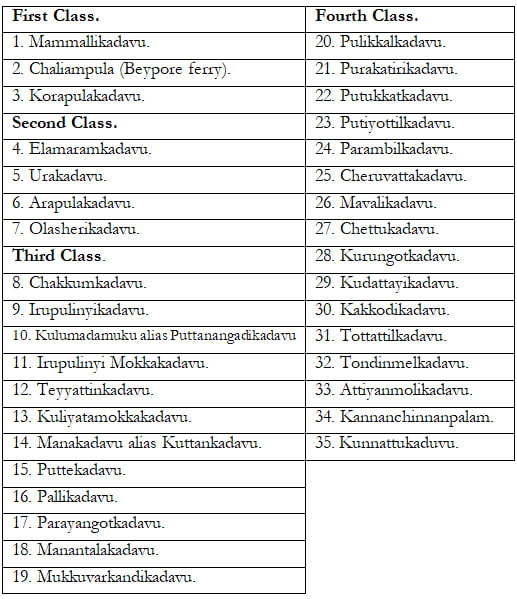

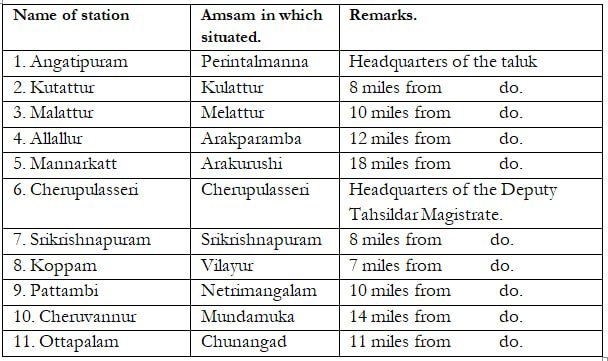

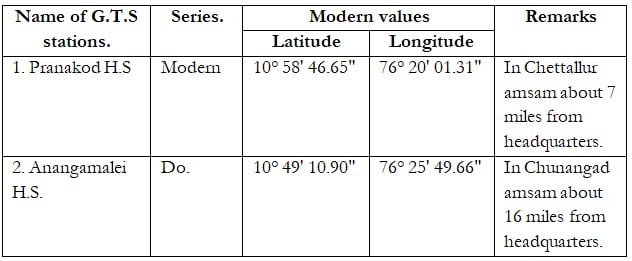

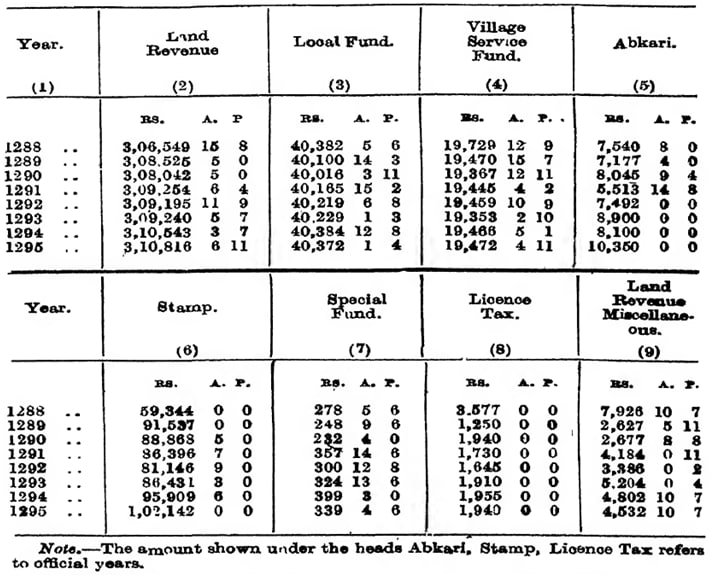

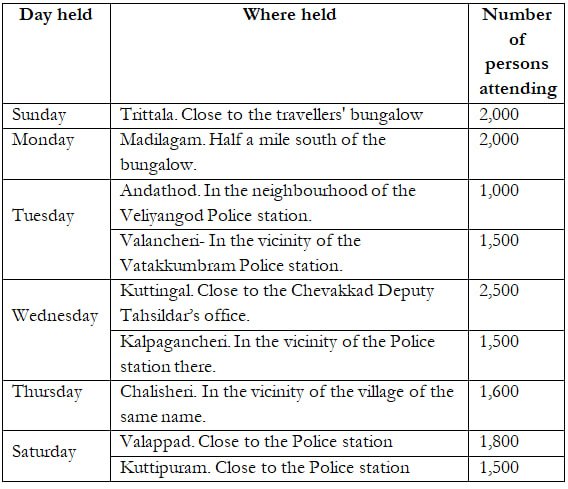

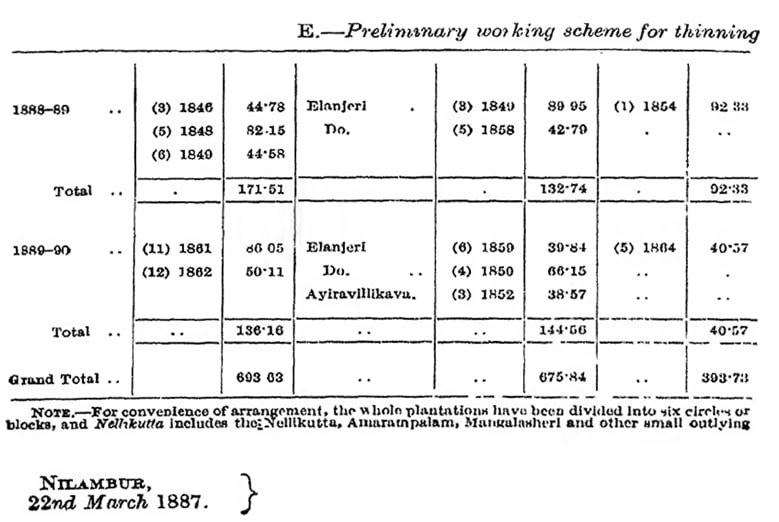

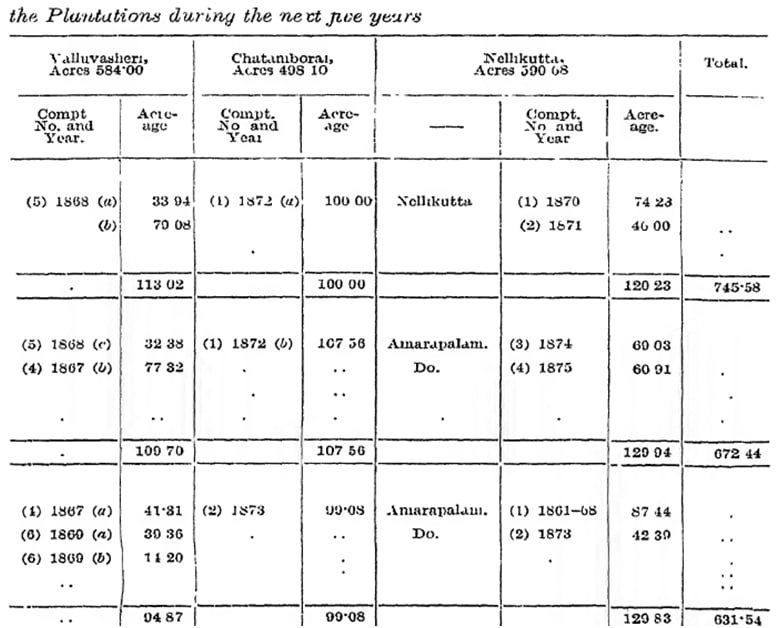

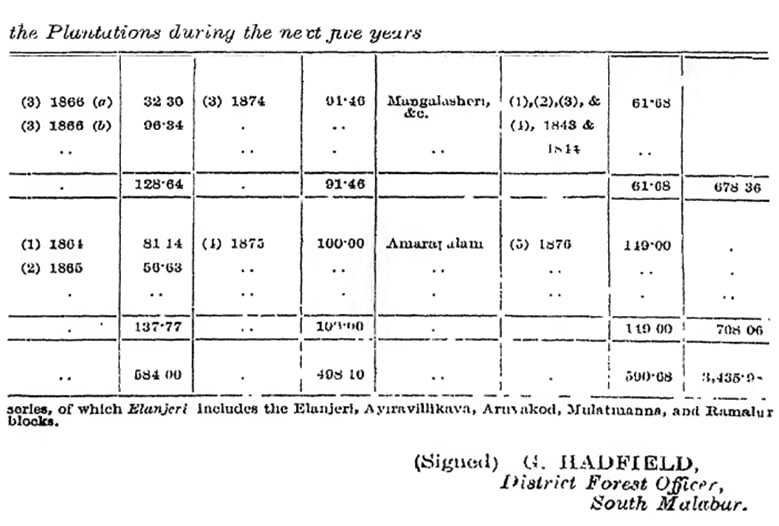

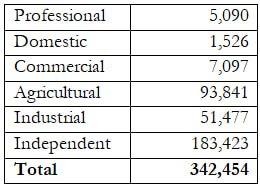

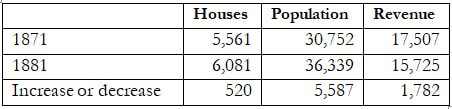

The contents of Volume Two are different. It is basically a book of Appendices. Most of them are in the form of tables and lists. However, there are a number of detailed writings also, wherein it is seen that some natives-of-the-subcontinent officials have written narratives, under their own names. The tabular lists include information about Statistics, Animals, Fishes, Birds, Butterflies, Timbre trees, Roads, Port rules, Malayalam proverbs, Mahl vocabulary, and a Collection of deeds. Next is a Glossary with notes and etymological headings attributed to Mr. Græme who was one of the English East India Company officials in Malabar.

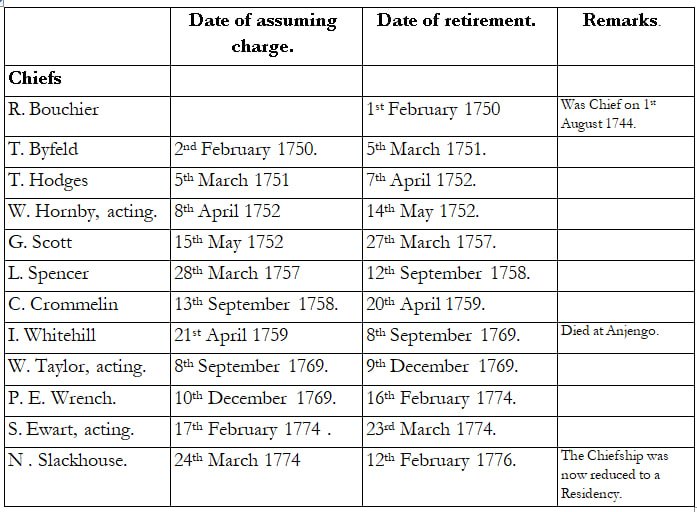

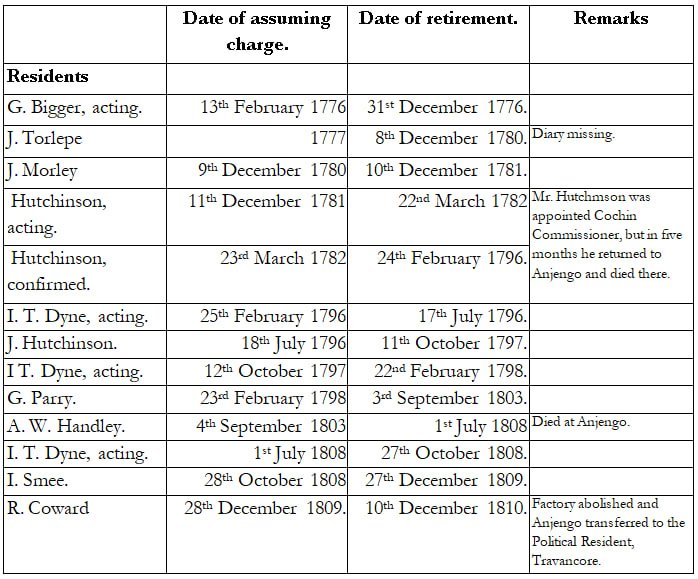

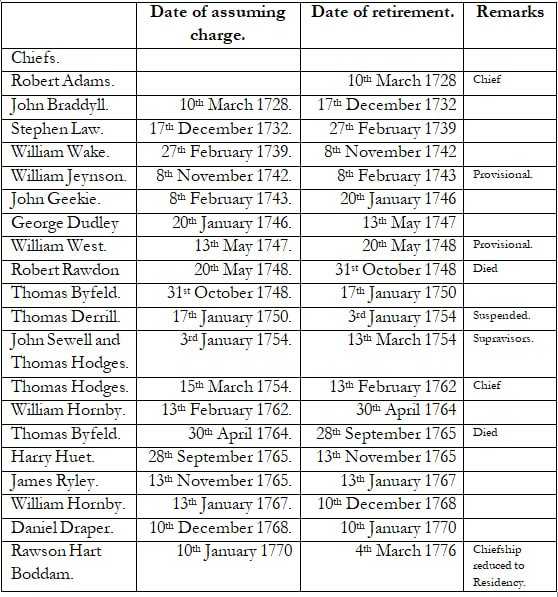

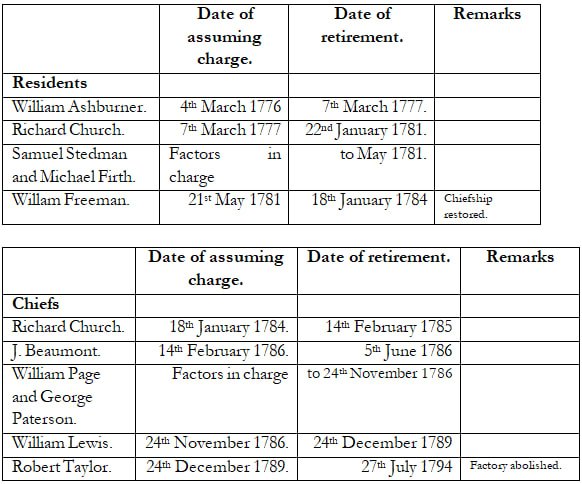

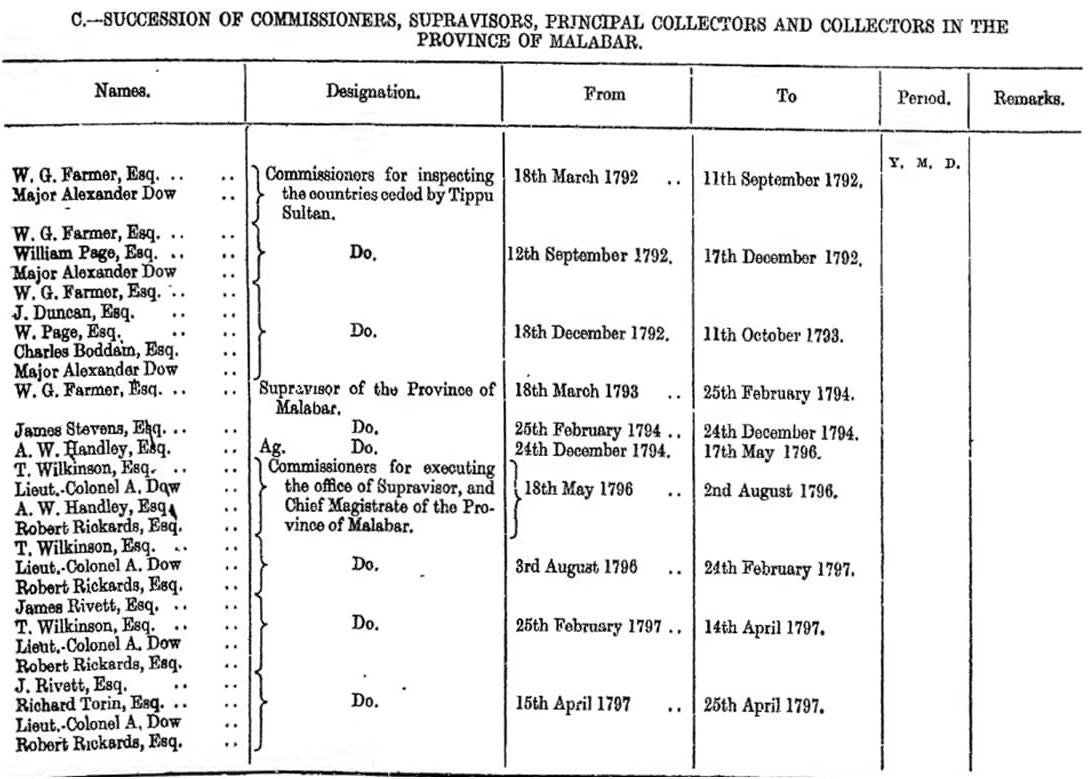

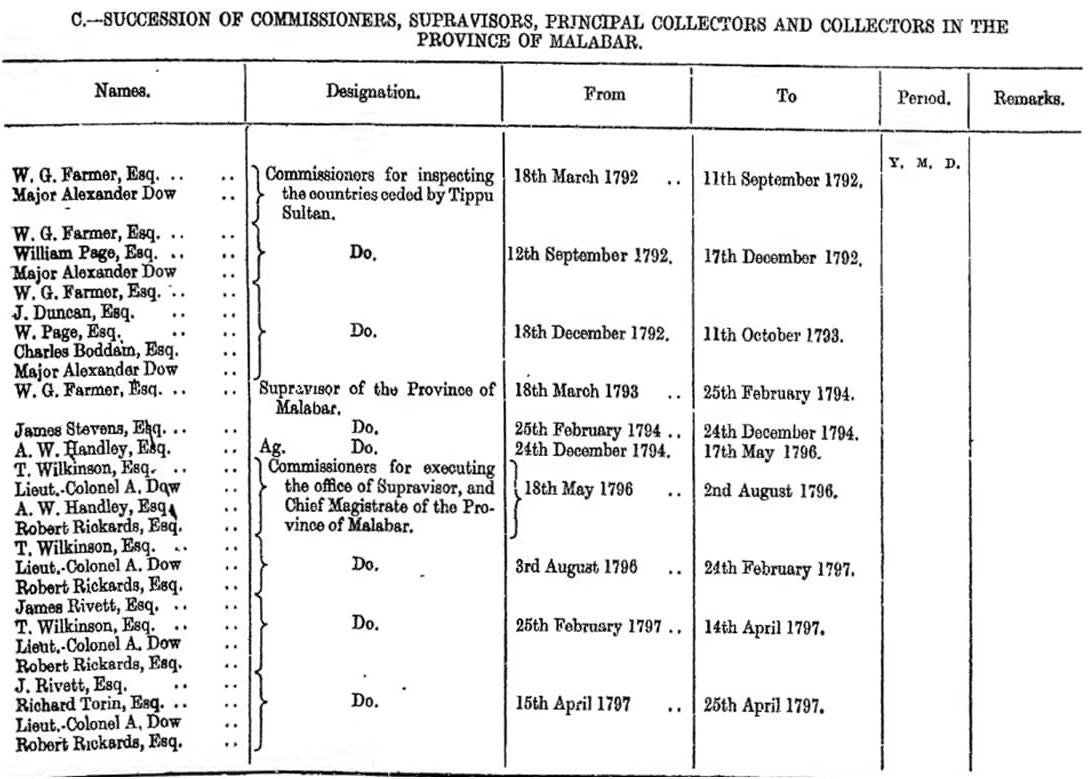

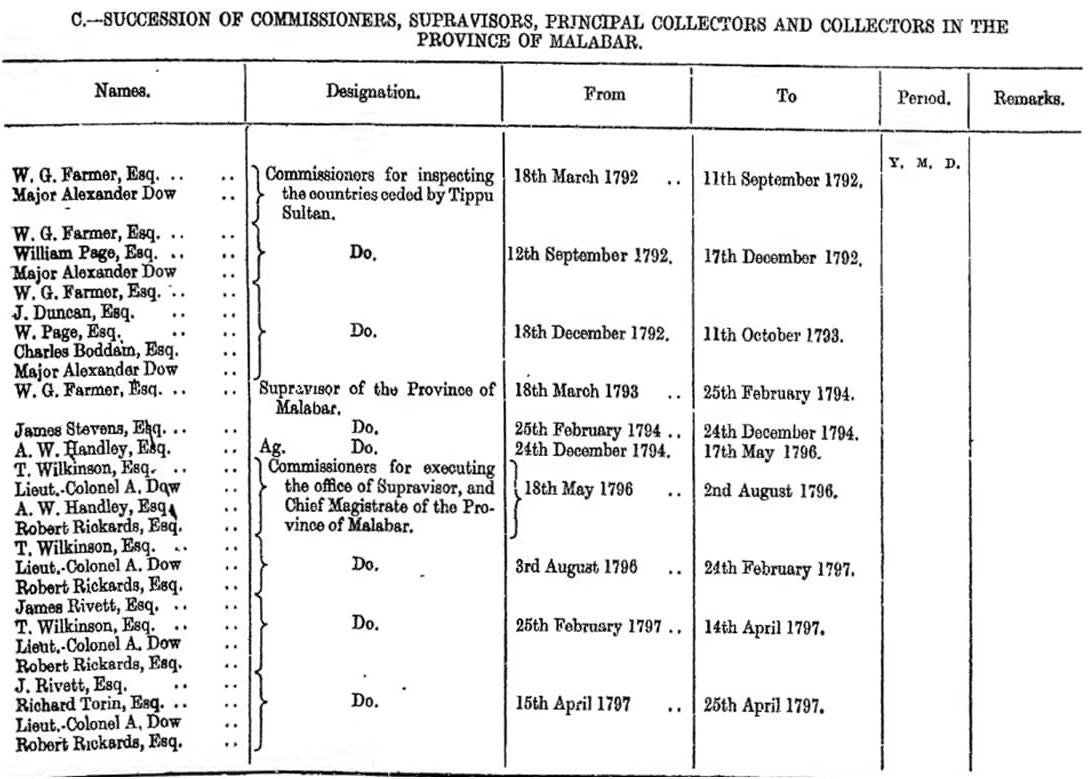

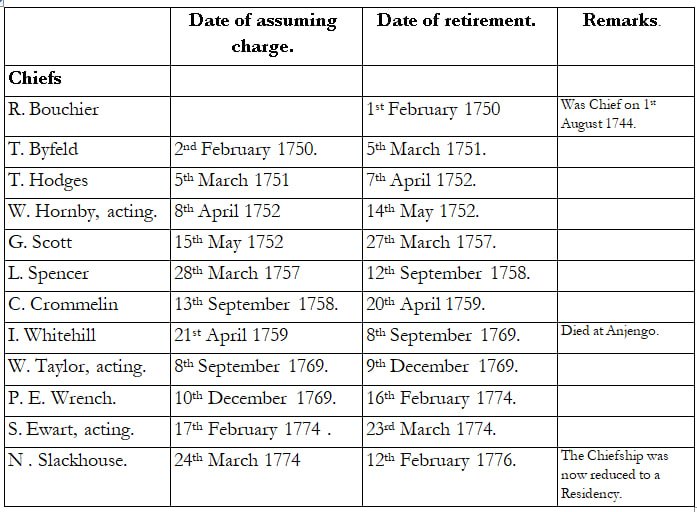

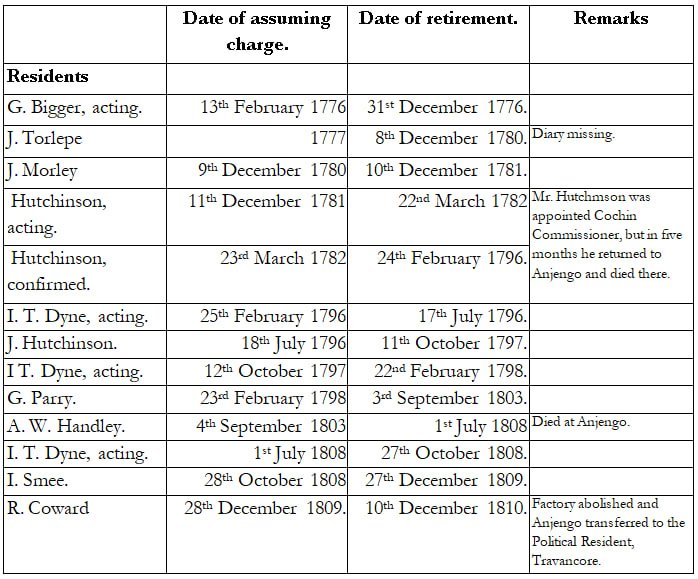

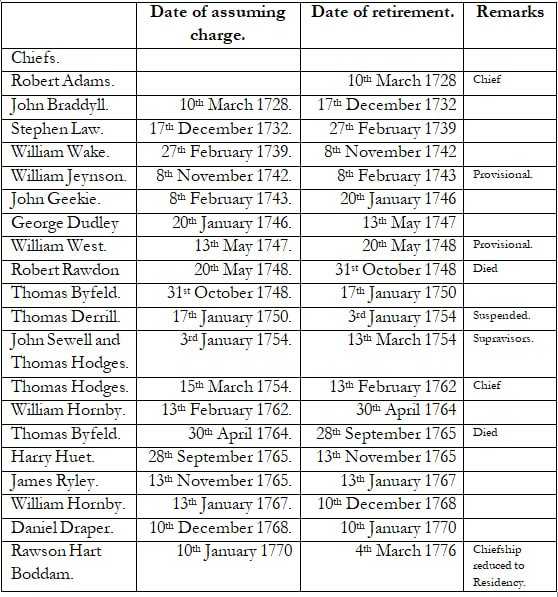

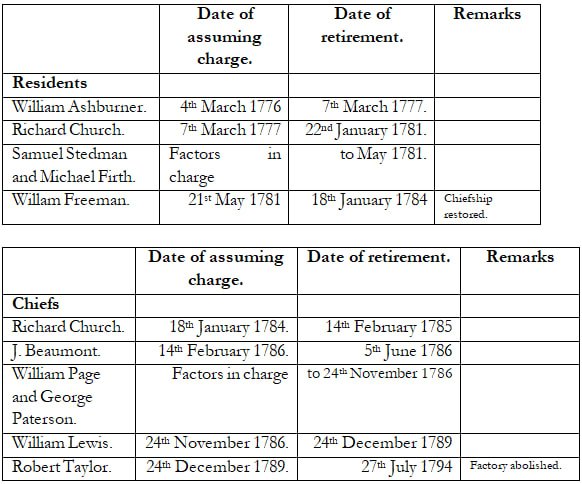

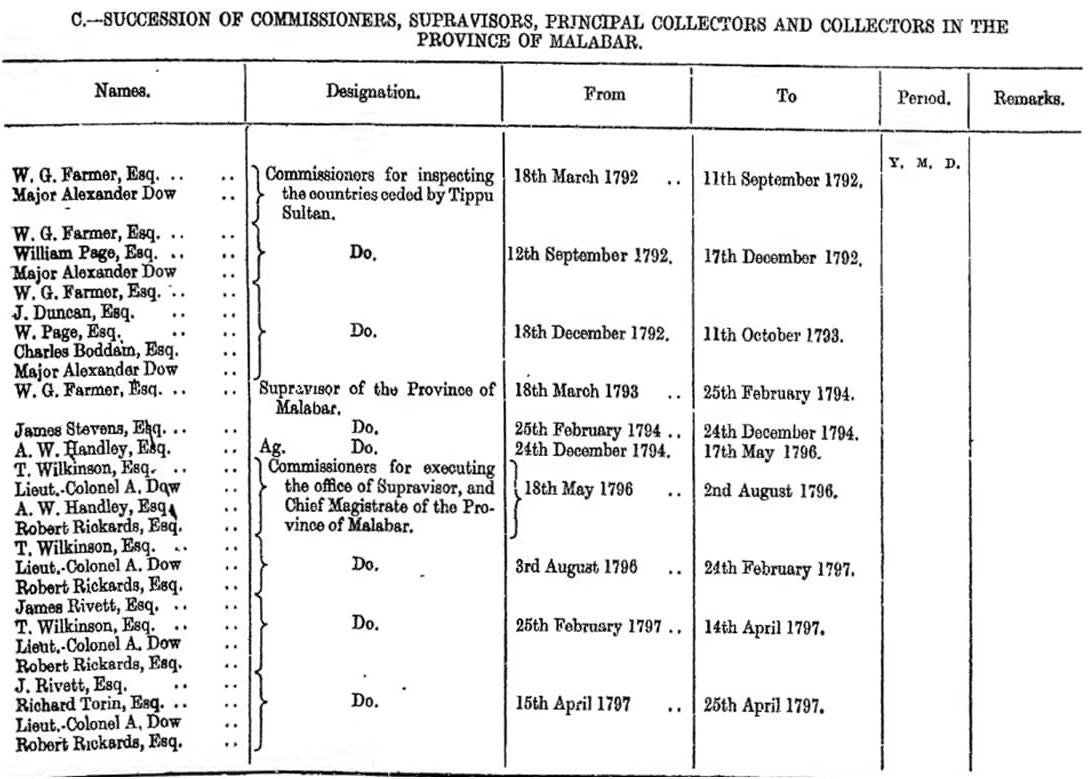

After this comes a list of names of the Chief Officers, Residents and Principal Collectors and Collectors who served in Malabar.

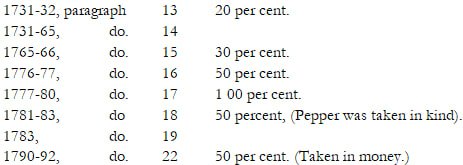

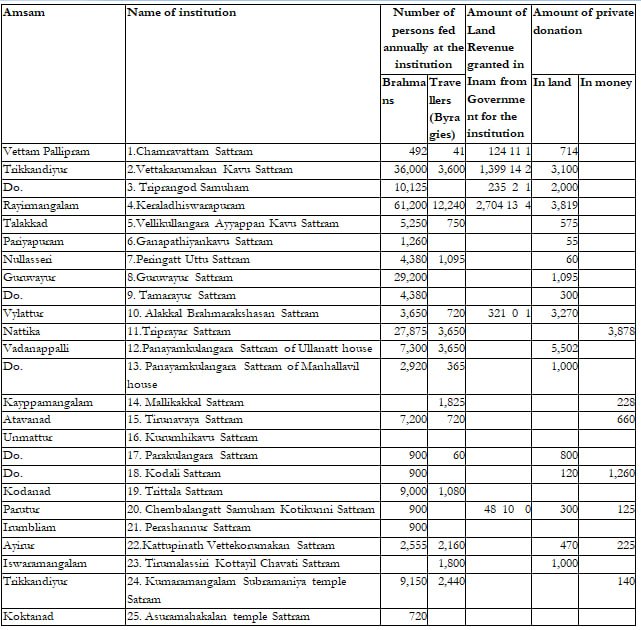

Next there are a lot of writings and chapters connected to agriculture and governmental income.

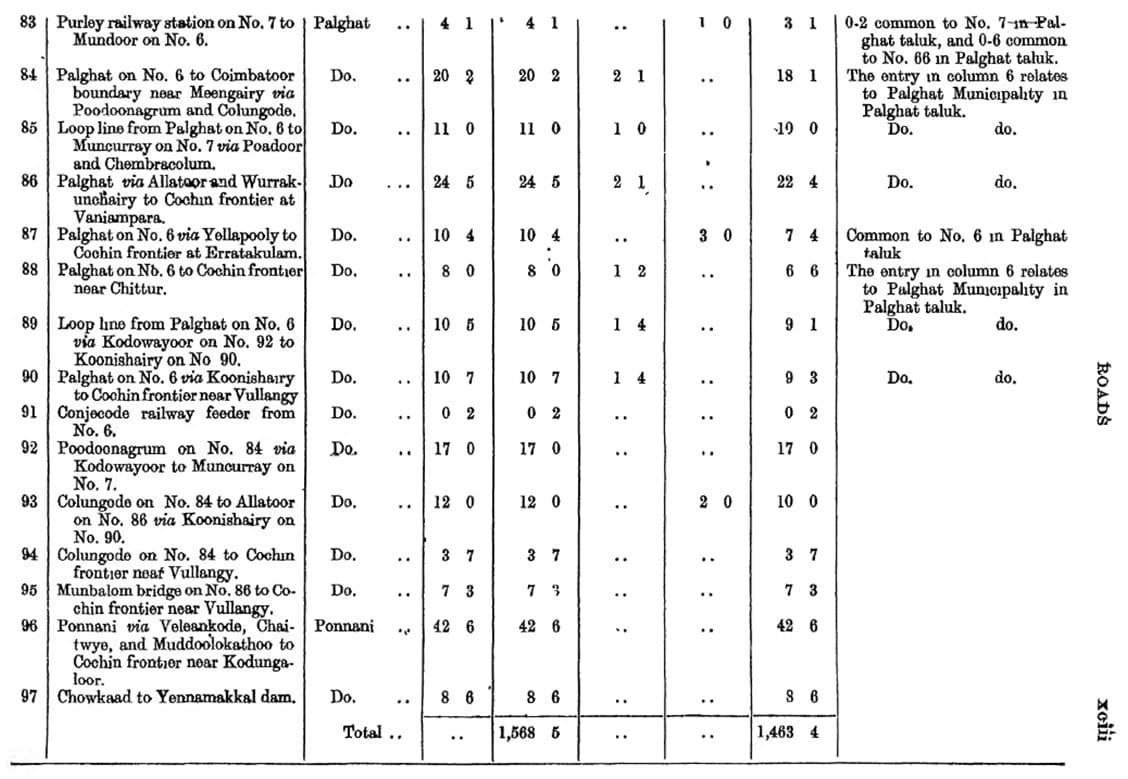

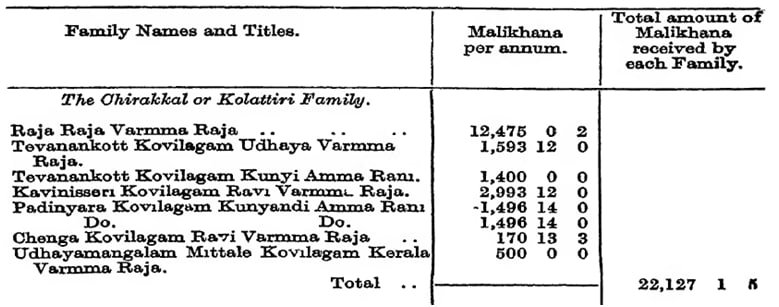

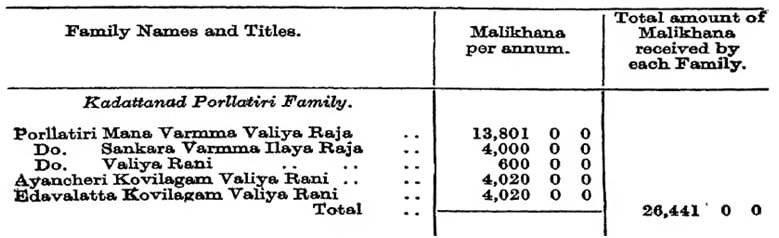

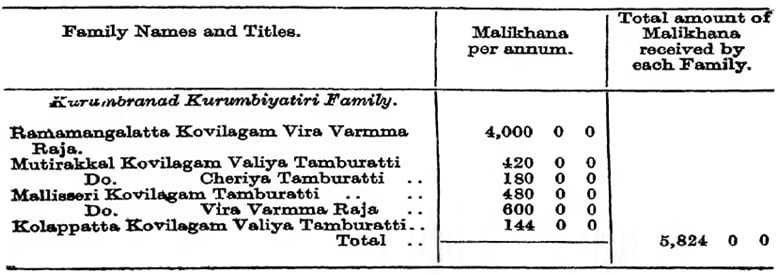

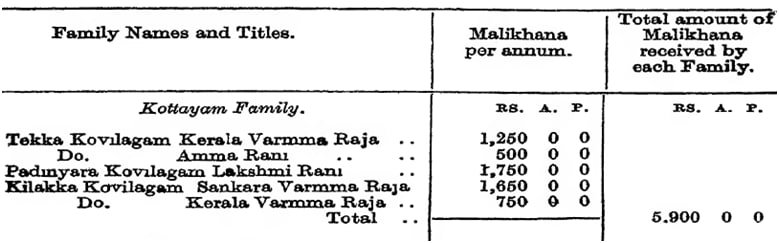

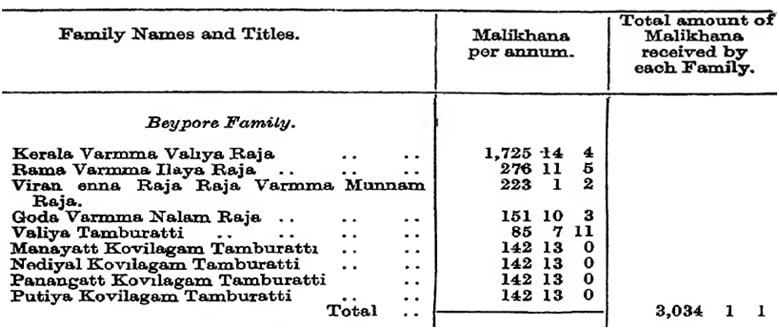

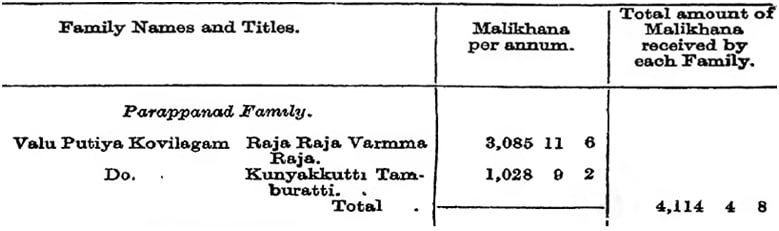

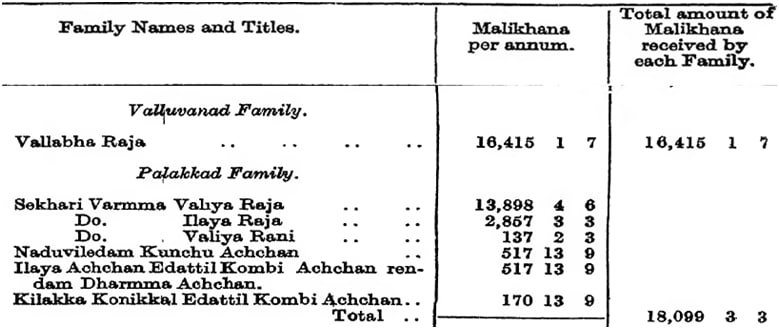

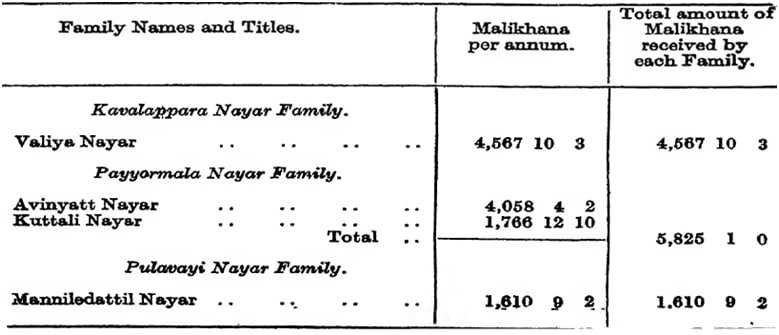

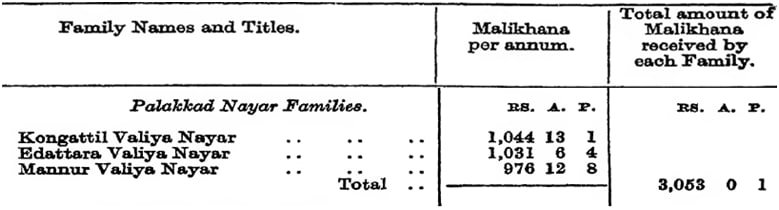

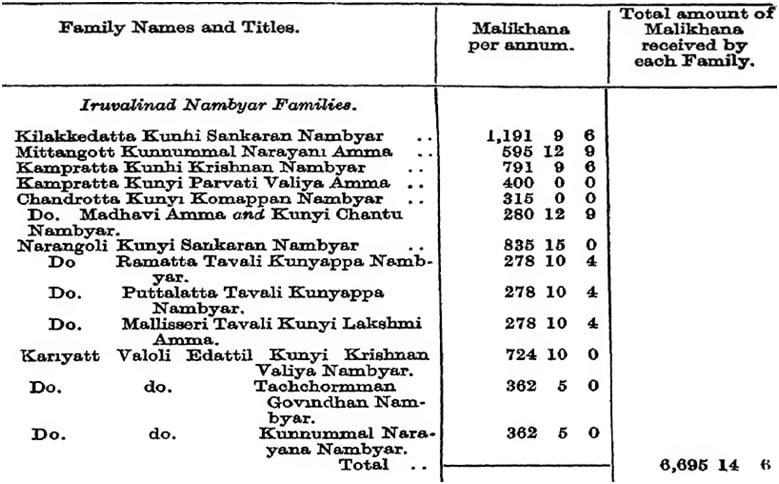

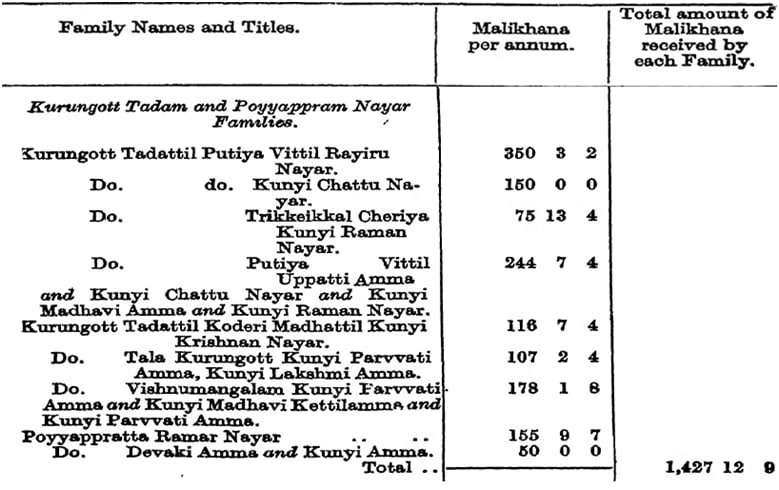

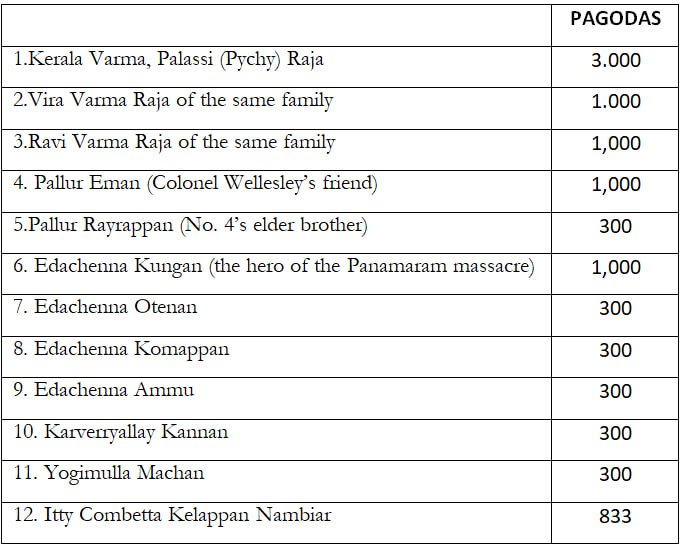

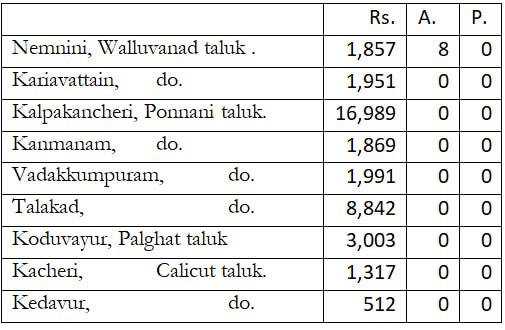

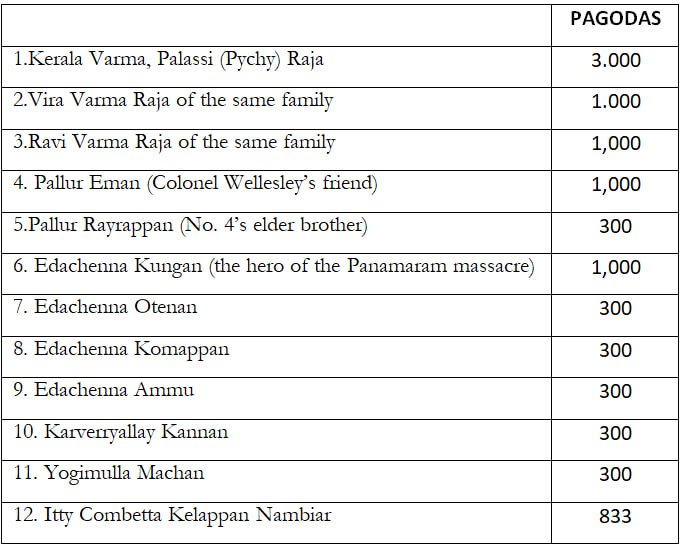

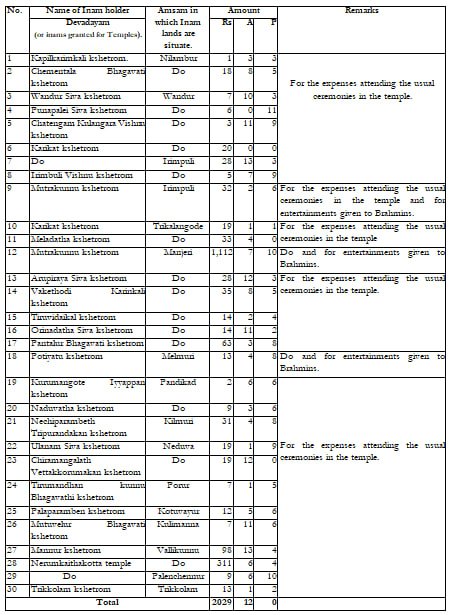

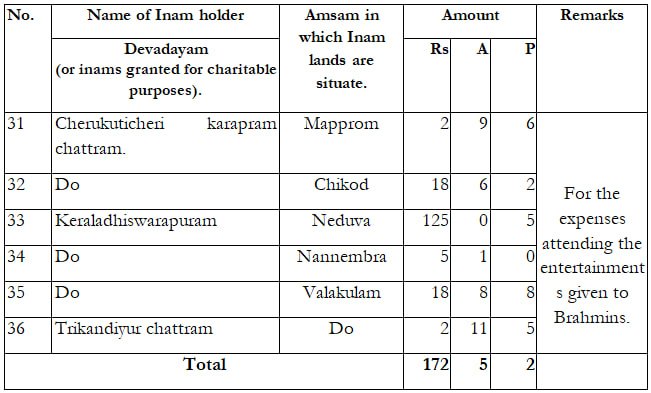

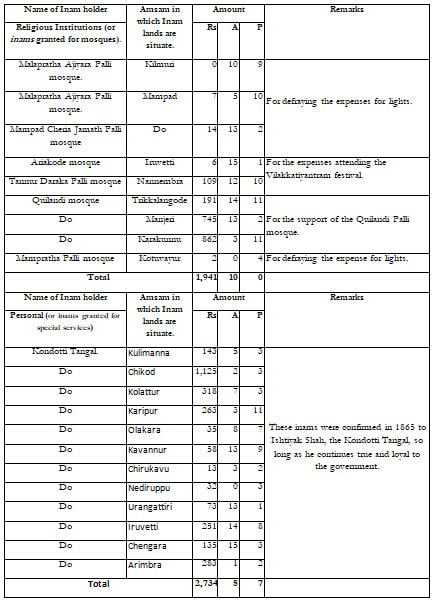

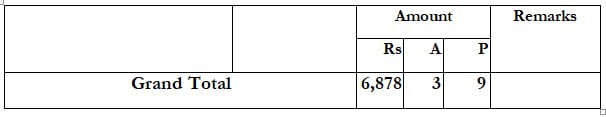

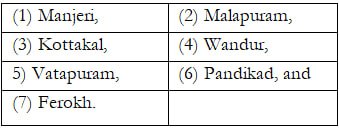

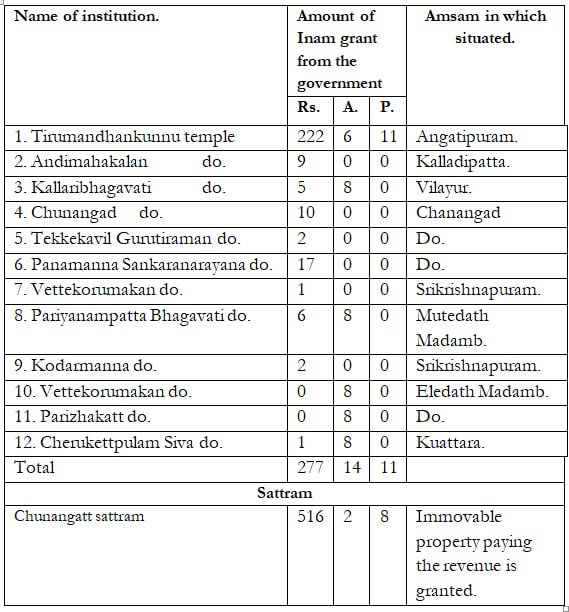

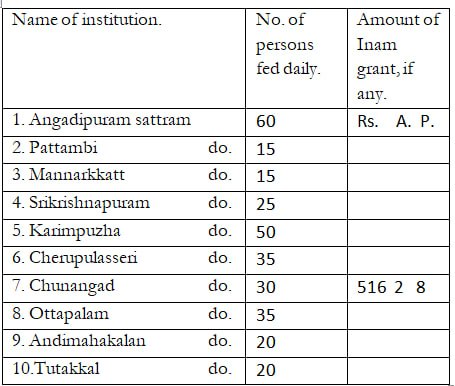

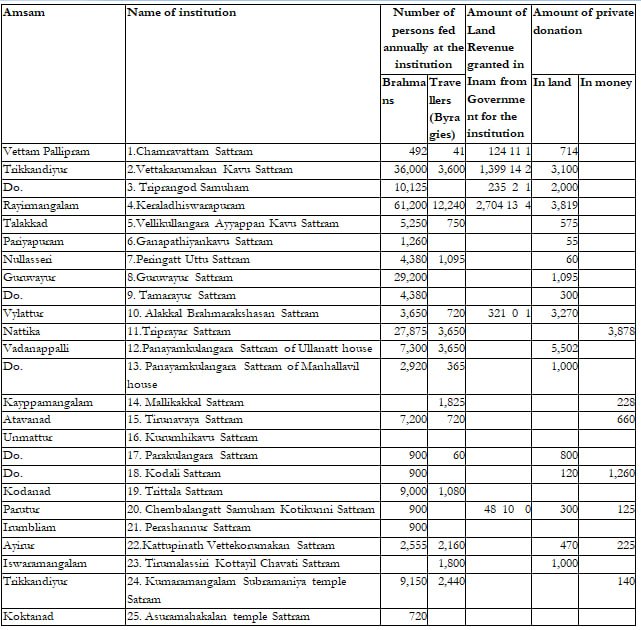

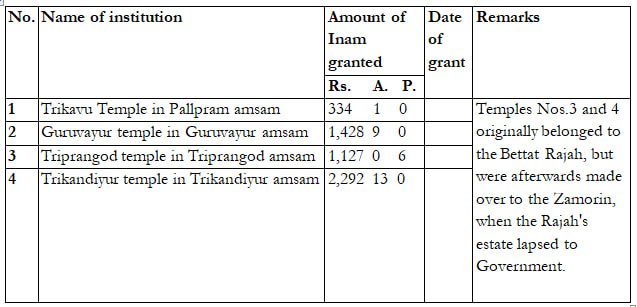

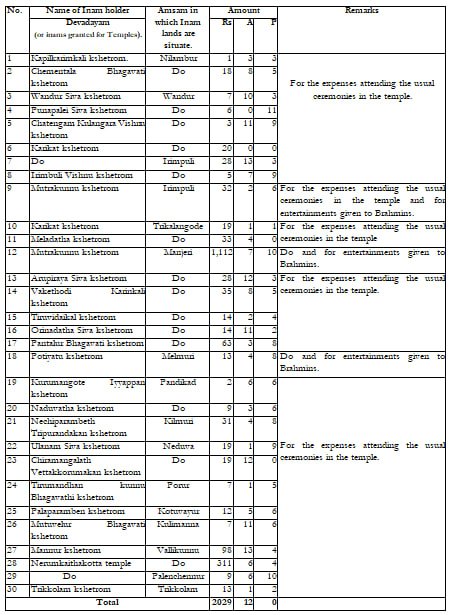

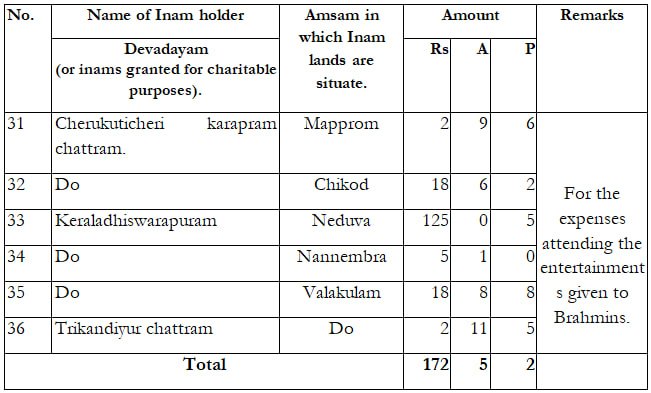

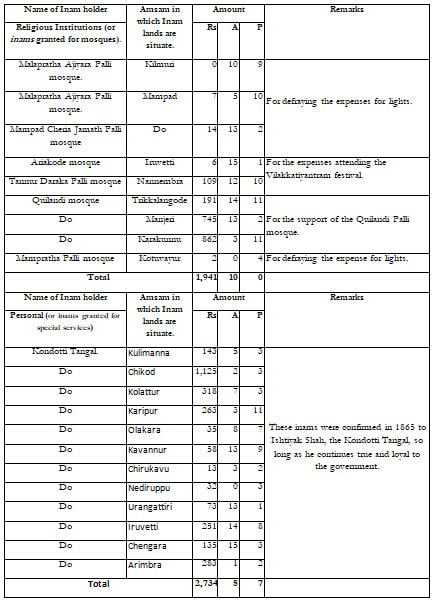

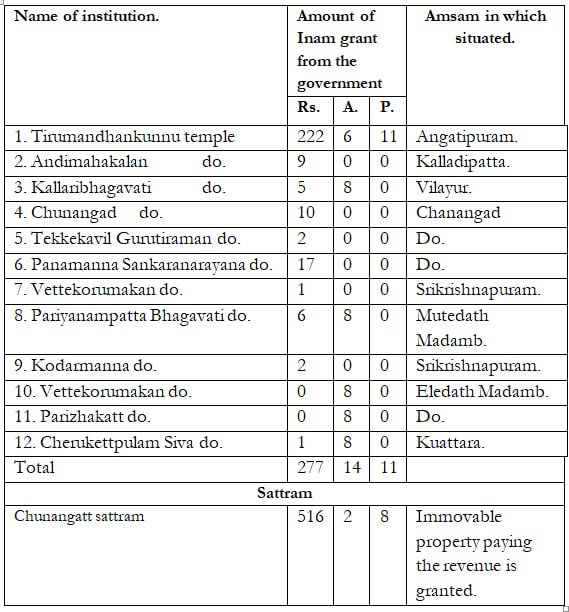

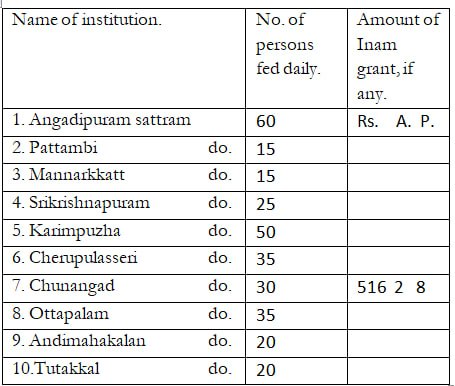

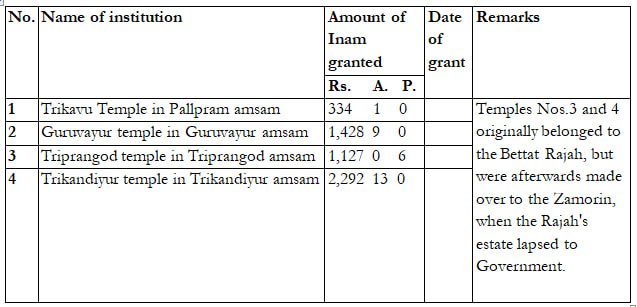

After this there is a List of Malikhana Recipients in Malabar. This more or less means that persons or families or religious institutions that received a sort of monthly or annual pension or some similar kind of monetary support from the English administration. The amount given to each entity is also given.

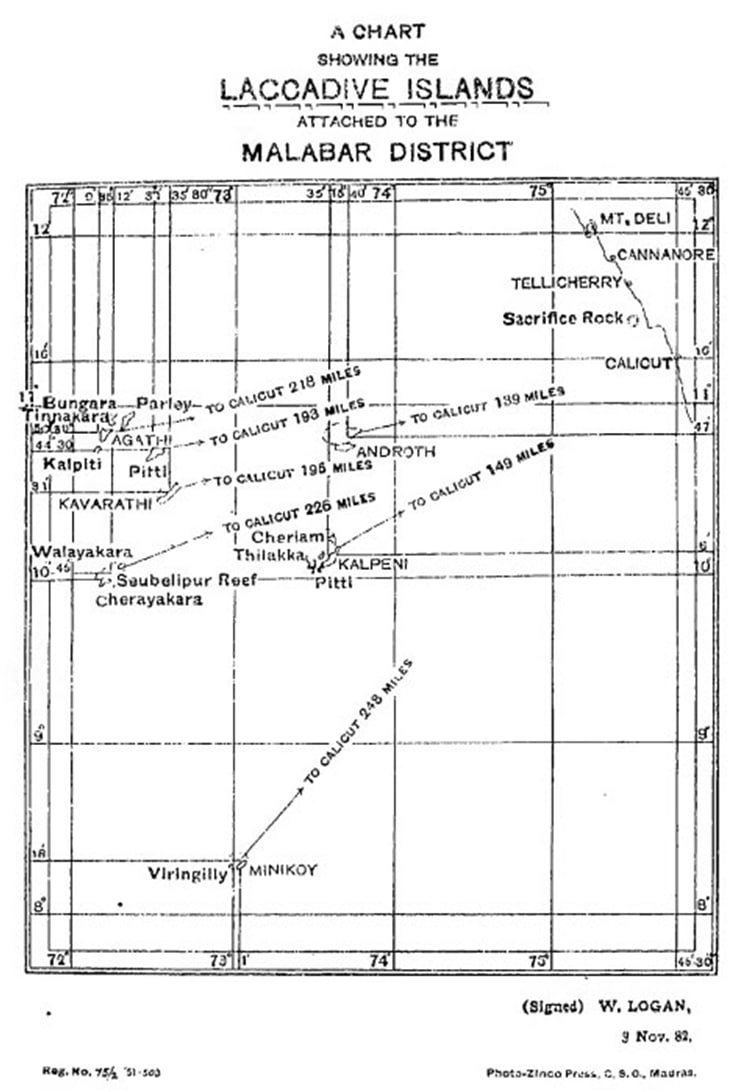

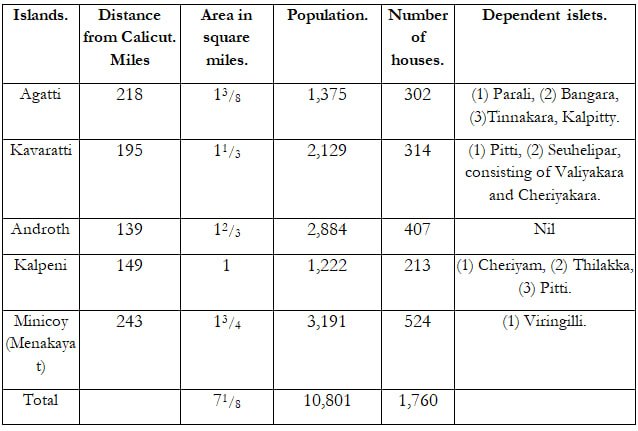

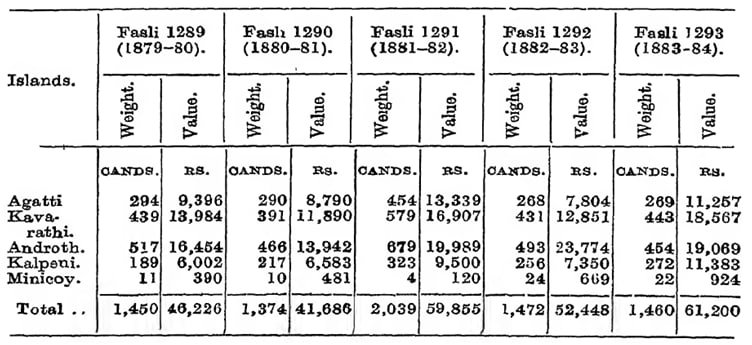

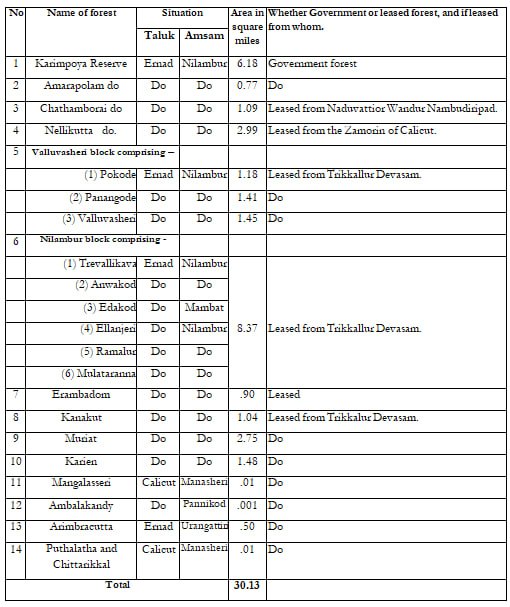

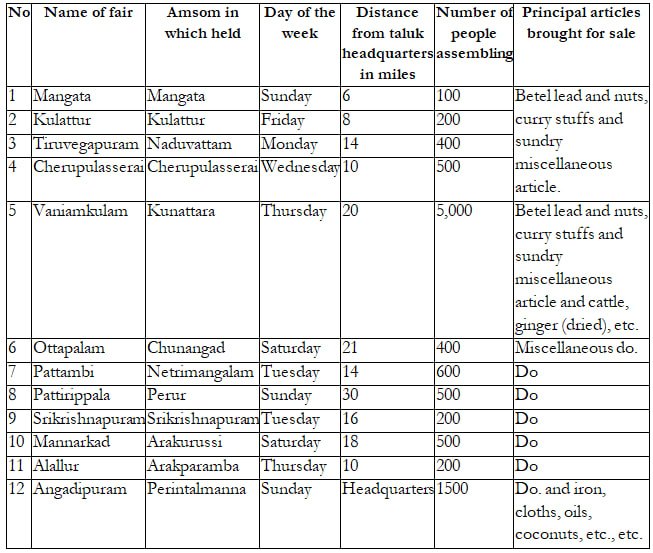

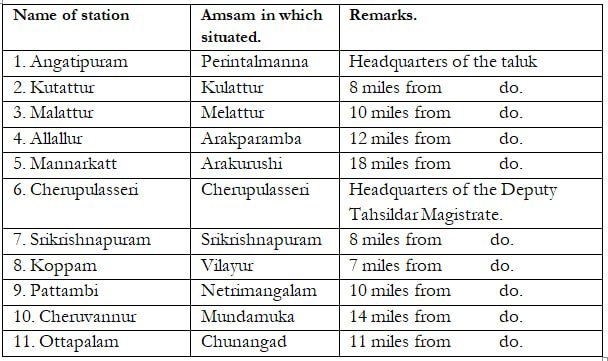

At the far end of all this comes a number of writings on the various Taluks in Malabar district. It includes the details of some of the Laccadive Islands also. These writings are reasonably descriptive enough.

From the perspective of pure statistical and chronological details, this book could be of very good contents. However, when seen from the underlying spirit that moves throughout the book, there are issues.

The book is clearly not the work or viewpoint one single person. As such to quote from this book, saying William Logan said this or that in his Malabar Manual, might not convey an honest information on what was Logan’s own version of understanding on any particular location.

The only location wherein he (or whoever has written this part) has written in a style, pose and gesture which is quite very steady and not much influenced by the native-land vested interests, in the location where he writes about the history by focusing on the dairy or logbook of the English East India Company Factory at Tellicherry.

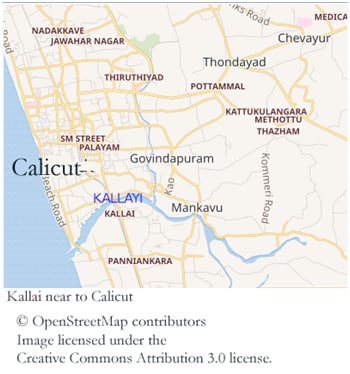

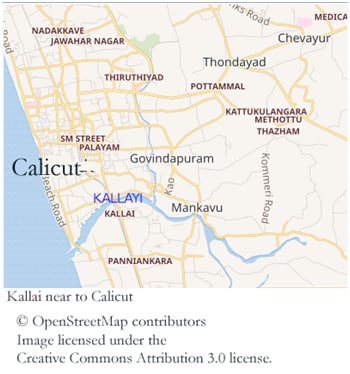

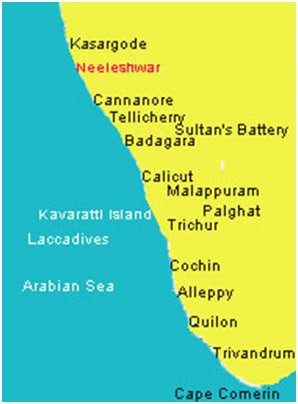

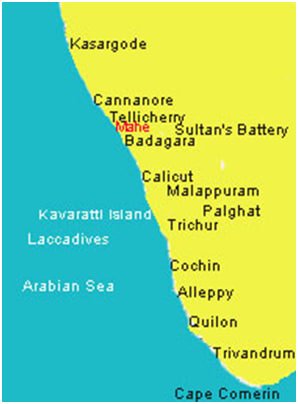

If this book is taken up for reading, it would be quite candidly seen that the history of modern Malabar that existed as social mood till around 1975, is connected to Tellicherry. And not to Calicut.

As for Trivandrum having any historical or social connections to Malabar is a theme fit for the understanding of the birdbrains.

The first chapter, The District deals with the physical features, rivers, mountains, the Fauna and Flora, Road, passes, railway, Port facilities etc. The Fauna and Flora section has been written by Rhodes Morgan, F.Z.S., Member of the British Ornithologists Union, District Forest Officer, Malabar.

The second chapter is about the people, population, villages, towns, habitation, rural organisation, language, literature and state of awareness of the people, caste issue and occupation, manners and customs, religions, famines, diseases and treatment.

The third chapter is about History of the location. Commencing from the traditions that gives a hint of the antiquity of the place, it moves on to time when Portuguese traders tried to set up a trading centre here. Then came the Dutch and after them the arrival of the English traders.

The fourth chapter is This Land. In this location, the attempts to understand the land tenures and land revenue systems are seen. The focus is on the English Factory at Tellicherry. The writing moves through the various minor historical incidences that slowly lead to the establishment of an English administrative system in Malabar.

With the exception of the Flora and Fauna section, I think that whole book has ostensibly been written by William Logan. That is the impression that comes out.

The contents of Volume Two are different. It is basically a book of Appendices. Most of them are in the form of tables and lists. However, there are a number of detailed writings also, wherein it is seen that some natives-of-the-subcontinent officials have written narratives, under their own names. The tabular lists include information about Statistics, Animals, Fishes, Birds, Butterflies, Timbre trees, Roads, Port rules, Malayalam proverbs, Mahl vocabulary, and a Collection of deeds. Next is a Glossary with notes and etymological headings attributed to Mr. Græme who was one of the English East India Company officials in Malabar.

After this comes a list of names of the Chief Officers, Residents and Principal Collectors and Collectors who served in Malabar.

Next there are a lot of writings and chapters connected to agriculture and governmental income.

After this there is a List of Malikhana Recipients in Malabar. This more or less means that persons or families or religious institutions that received a sort of monthly or annual pension or some similar kind of monetary support from the English administration. The amount given to each entity is also given.

At the far end of all this comes a number of writings on the various Taluks in Malabar district. It includes the details of some of the Laccadive Islands also. These writings are reasonably descriptive enough.

From the perspective of pure statistical and chronological details, this book could be of very good contents. However, when seen from the underlying spirit that moves throughout the book, there are issues.

The book is clearly not the work or viewpoint one single person. As such to quote from this book, saying William Logan said this or that in his Malabar Manual, might not convey an honest information on what was Logan’s own version of understanding on any particular location.

The only location wherein he (or whoever has written this part) has written in a style, pose and gesture which is quite very steady and not much influenced by the native-land vested interests, in the location where he writes about the history by focusing on the dairy or logbook of the English East India Company Factory at Tellicherry.

If this book is taken up for reading, it would be quite candidly seen that the history of modern Malabar that existed as social mood till around 1975, is connected to Tellicherry. And not to Calicut.

As for Trivandrum having any historical or social connections to Malabar is a theme fit for the understanding of the birdbrains.

Last edited by VED on Fri Feb 16, 2024 12:19 pm, edited 3 times in total.

4. My own insertions

4 #

I did get to have a very rudimentary reading when I was placing the text on the MS Word document file. After that I went to place around 180 or more images. These images were mostly taken from online sources. Their image usage licence has been given along with them. This time also I got to read the text.

After these two readings the general layout of the book and its contents are in my head now. However, the details have vanished from my head. But then, I am aware of the various and varying mentalities, spirit and urges that have done their work in this book.

So I will have to take the items one by one. It is definitely going to be a long haul. However, I am used to slow-paced work.

After these two readings the general layout of the book and its contents are in my head now. However, the details have vanished from my head. But then, I am aware of the various and varying mentalities, spirit and urges that have done their work in this book.

So I will have to take the items one by one. It is definitely going to be a long haul. However, I am used to slow-paced work.

Last edited by VED on Fri Feb 16, 2024 12:20 pm, edited 4 times in total.

5. The first impressions about the contents

5 #

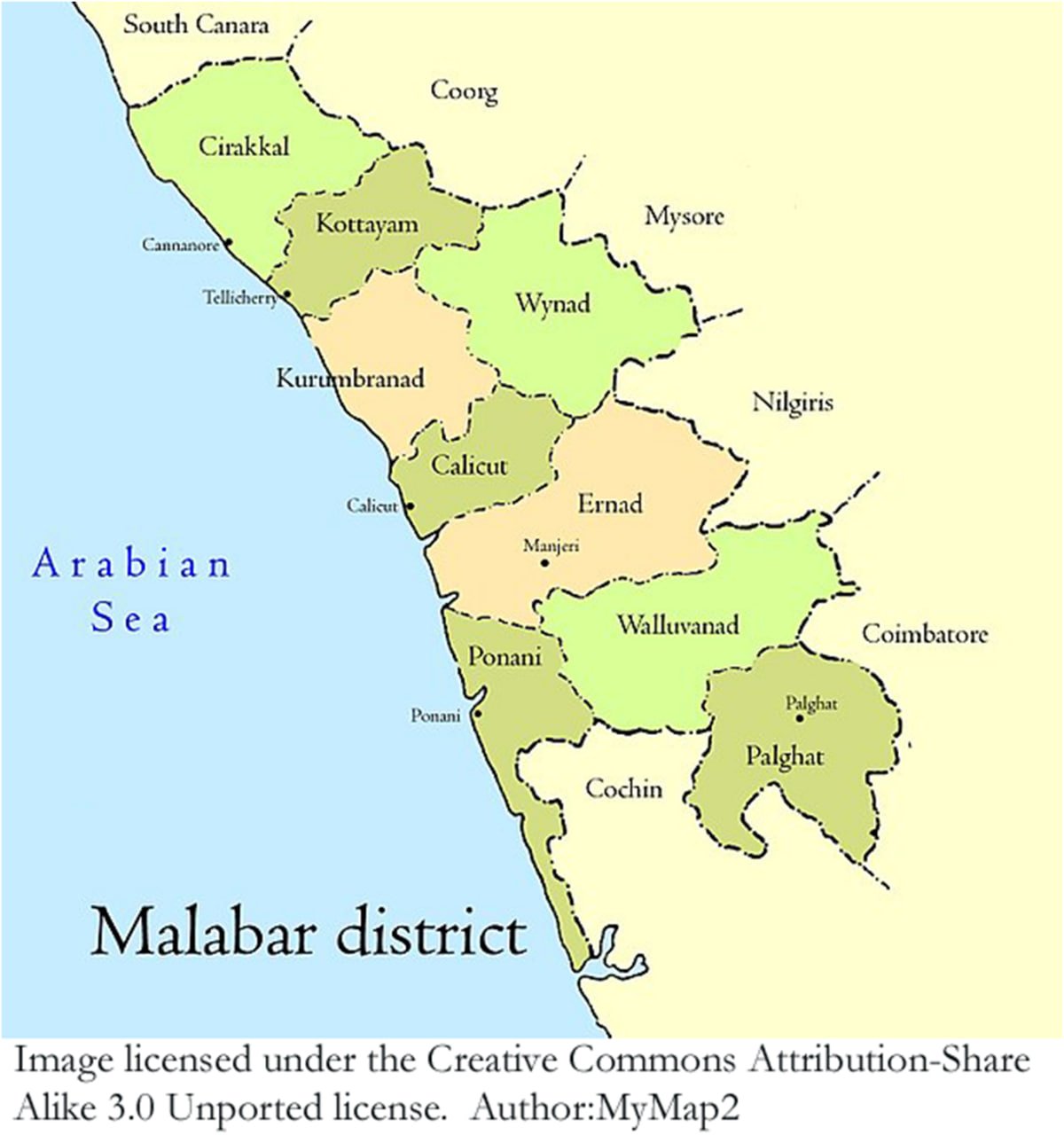

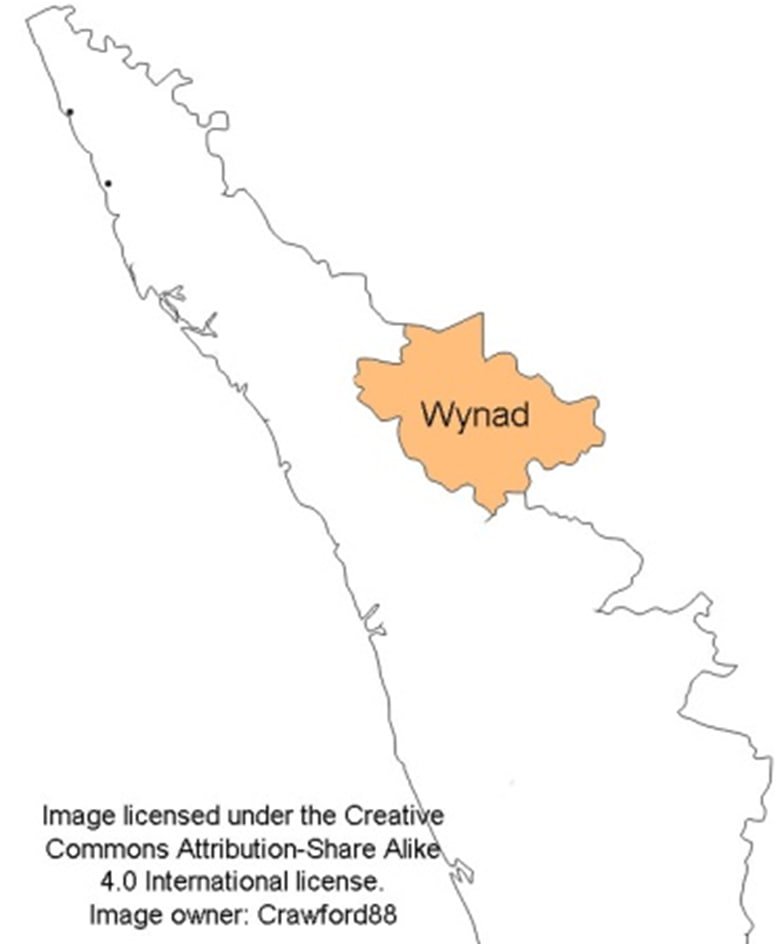

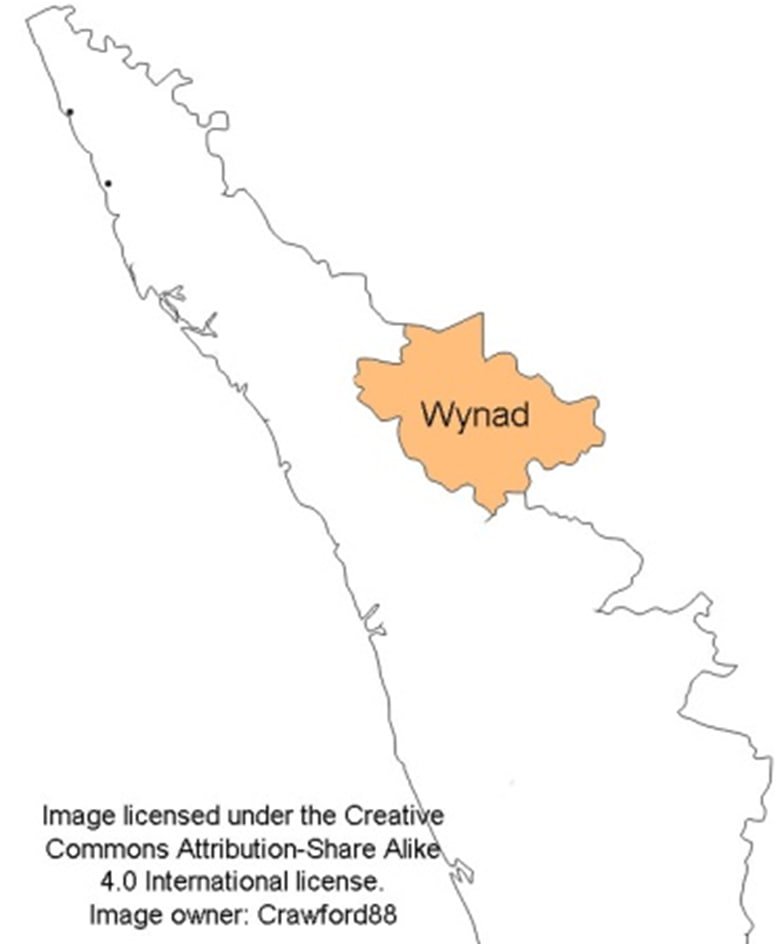

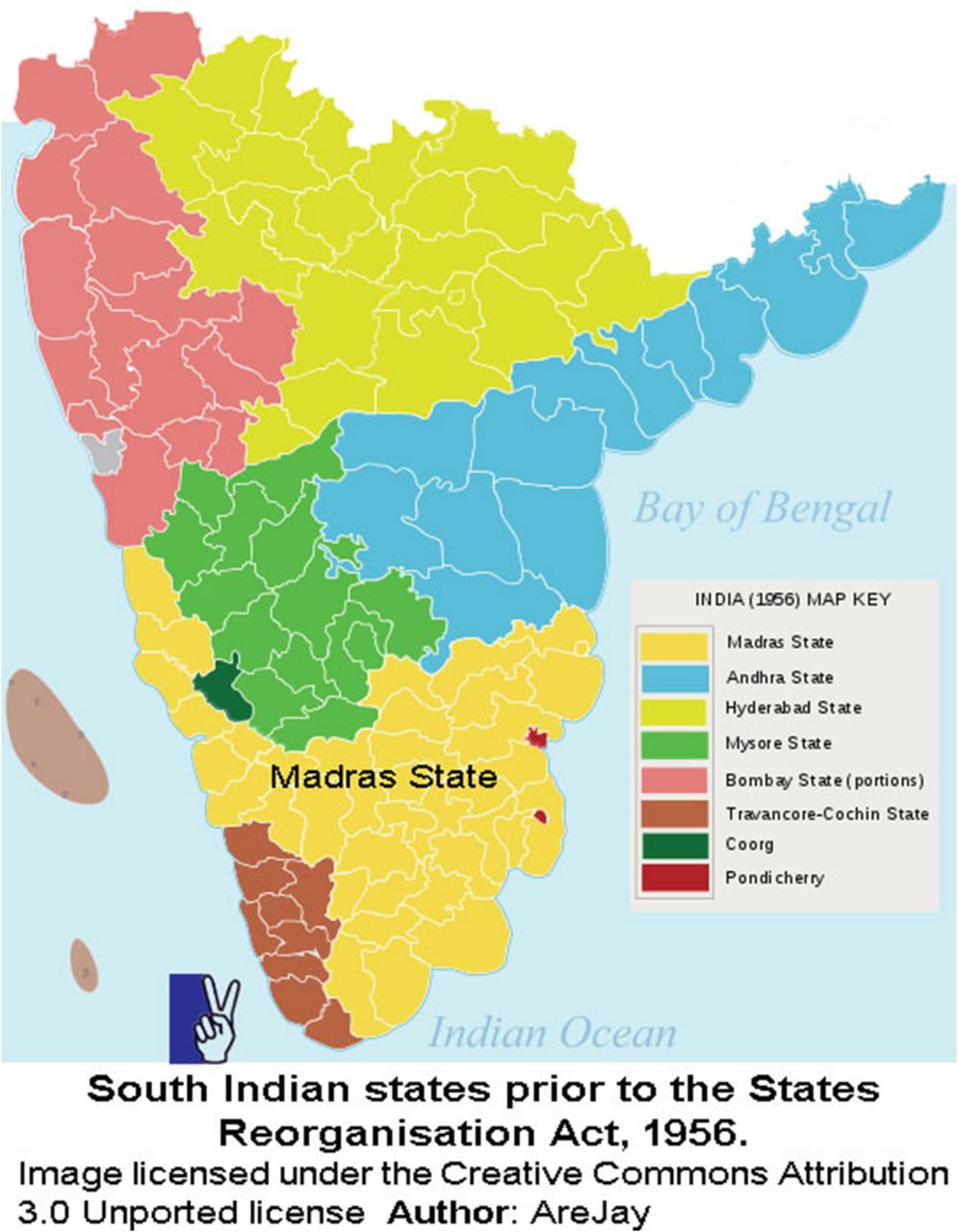

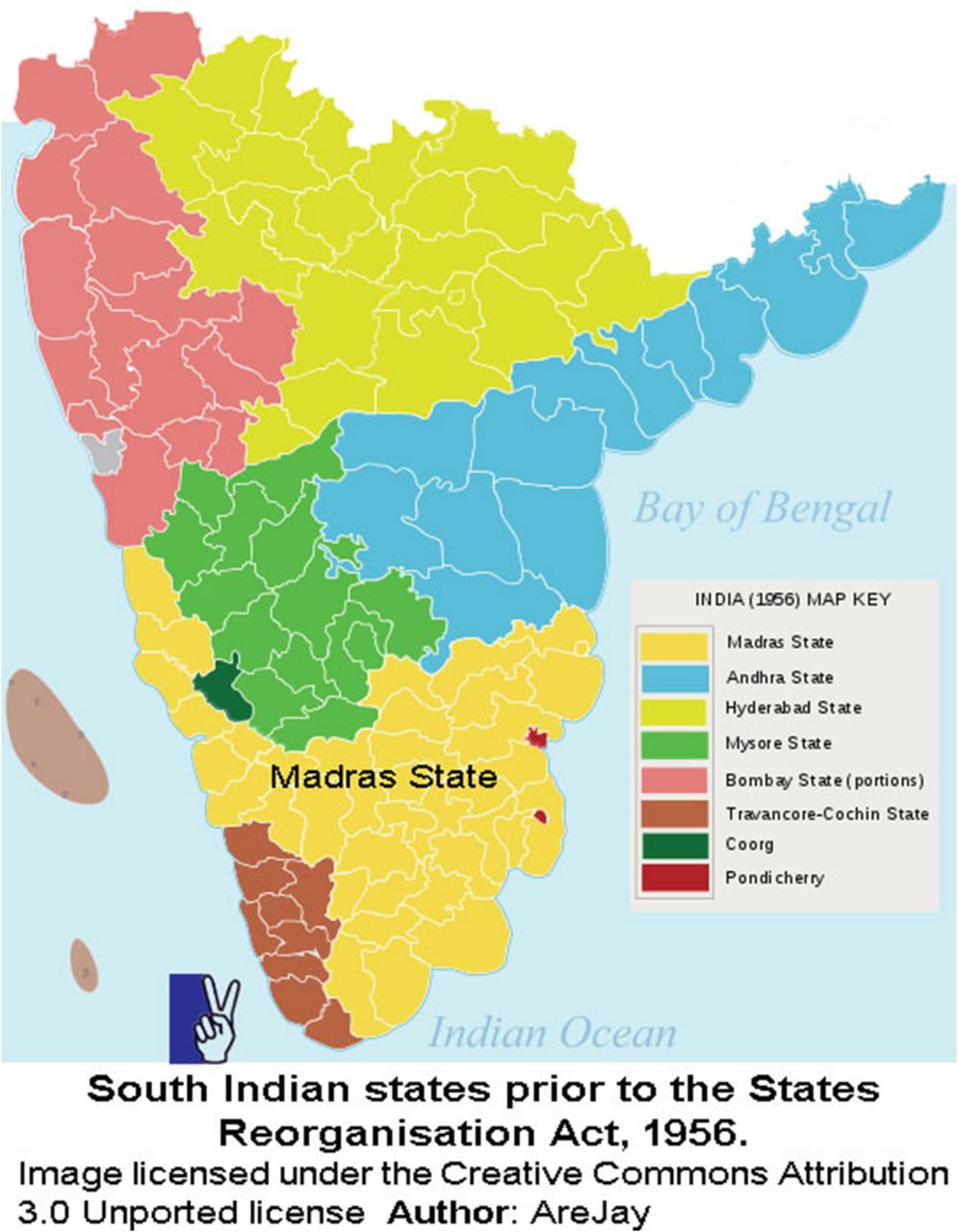

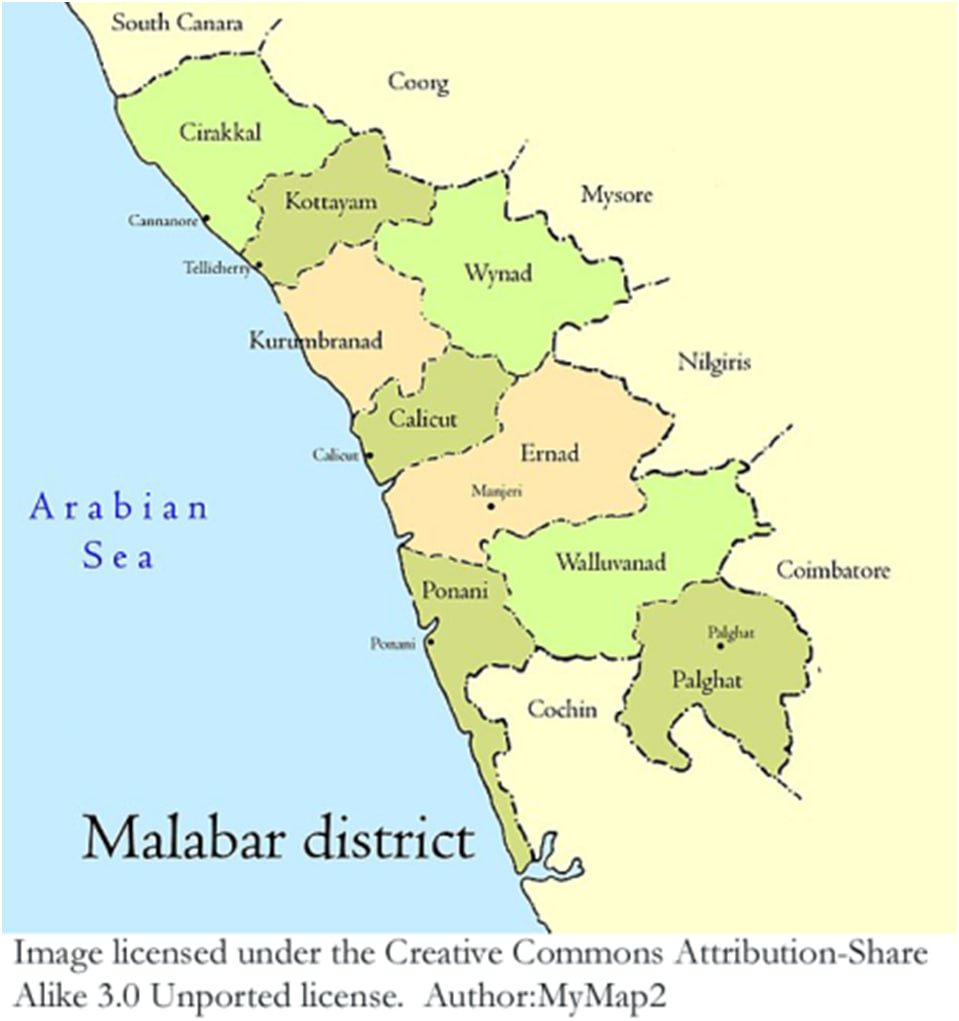

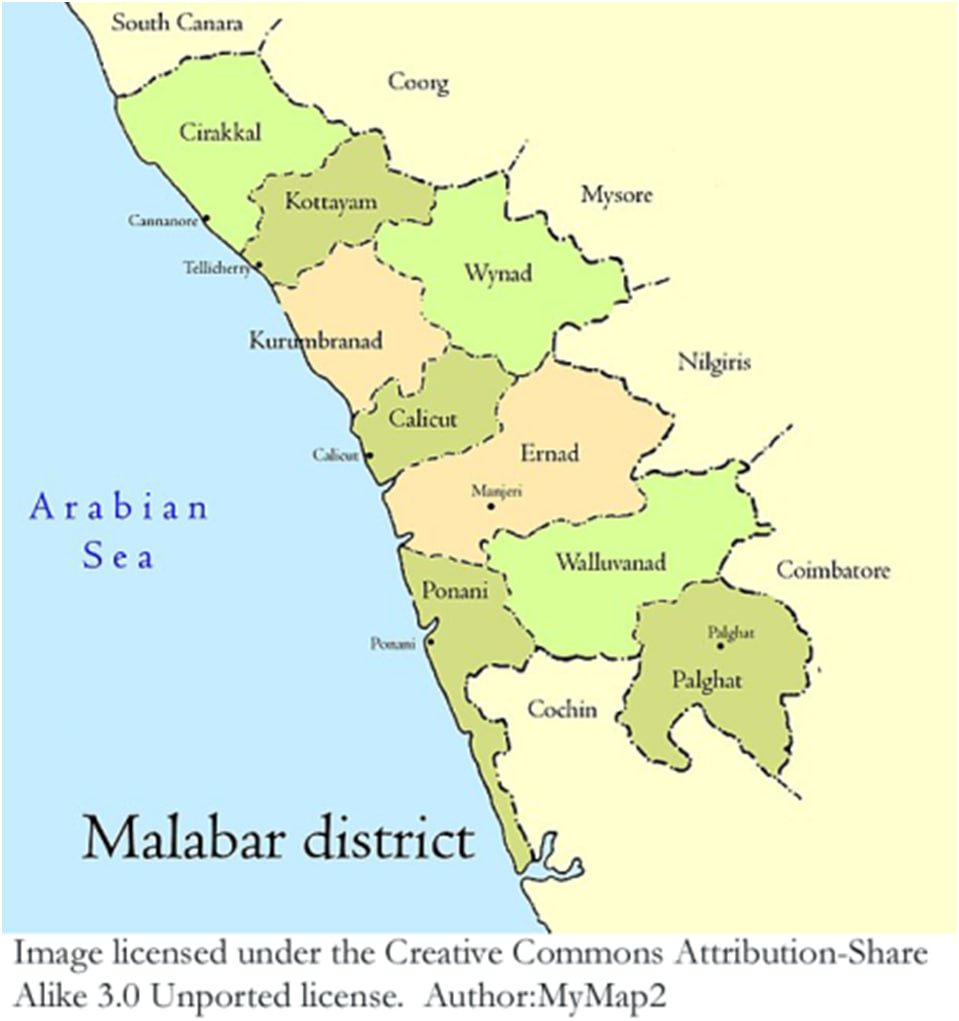

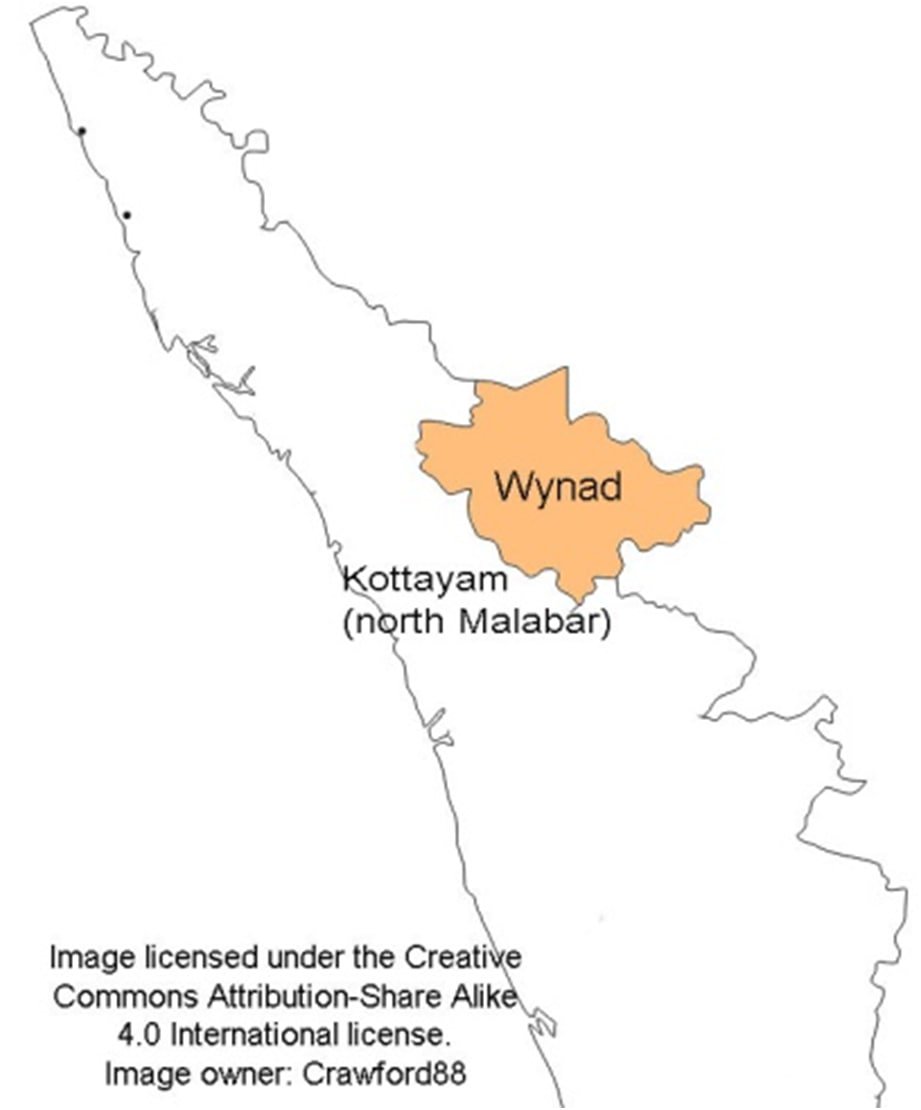

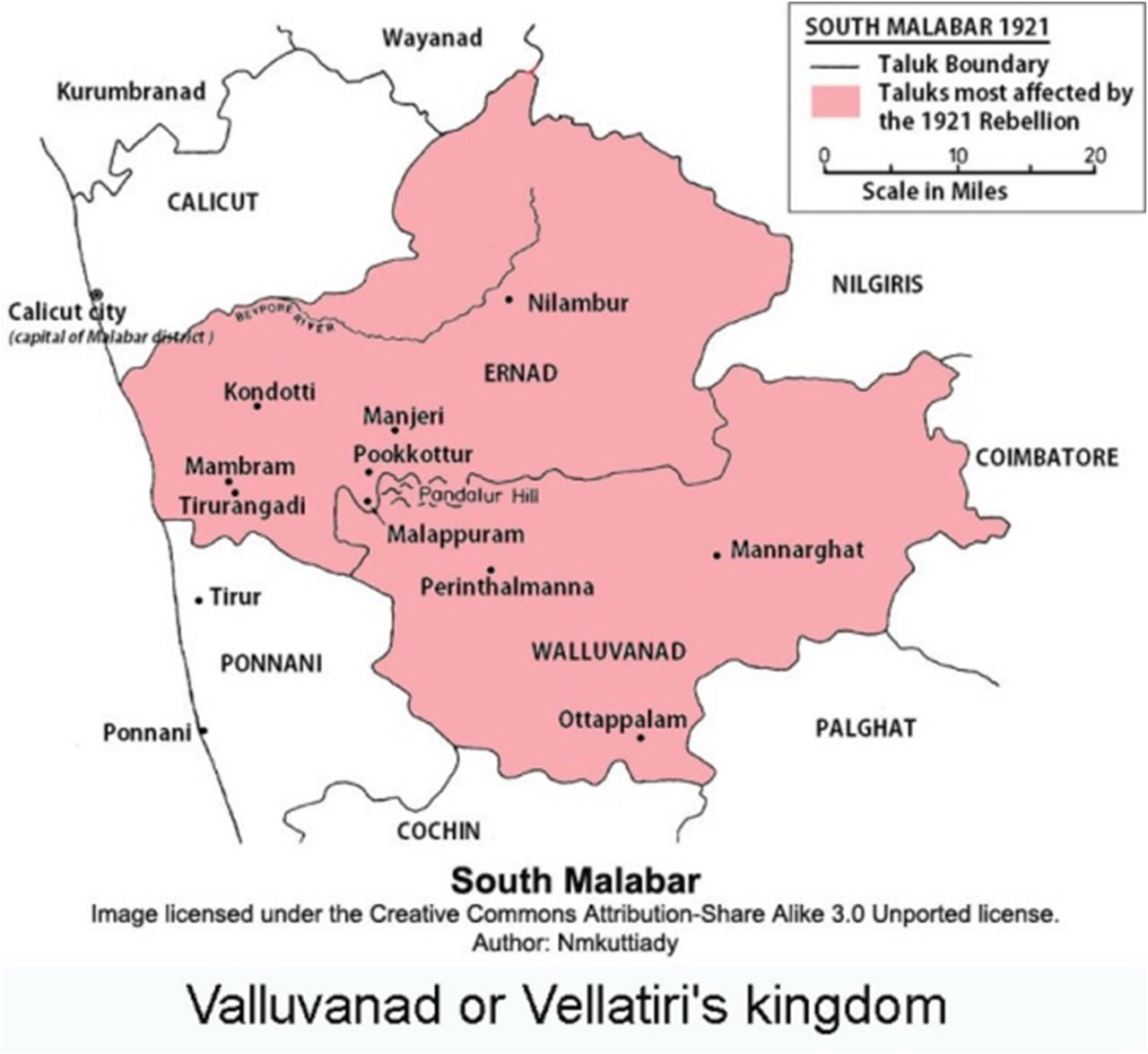

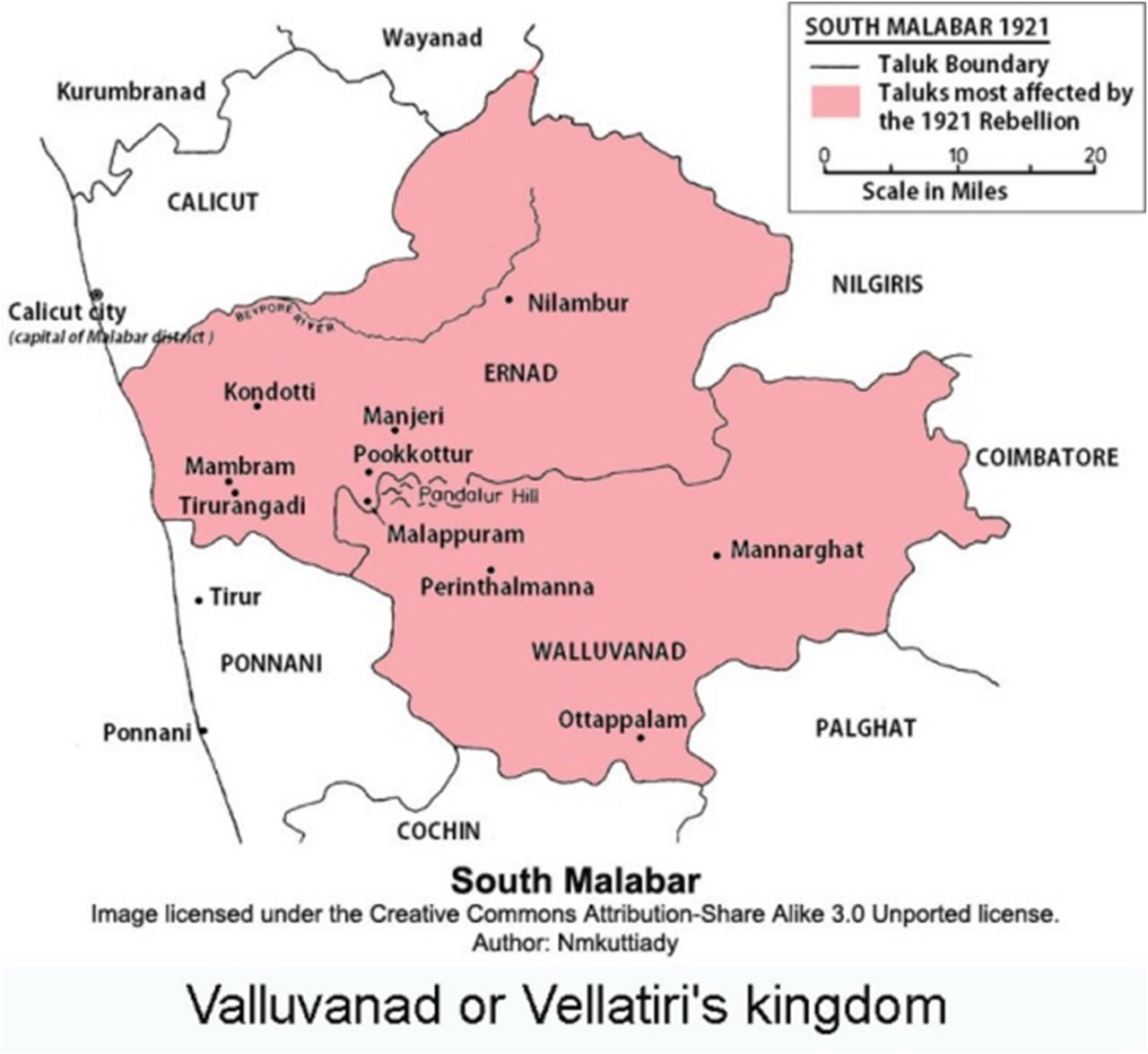

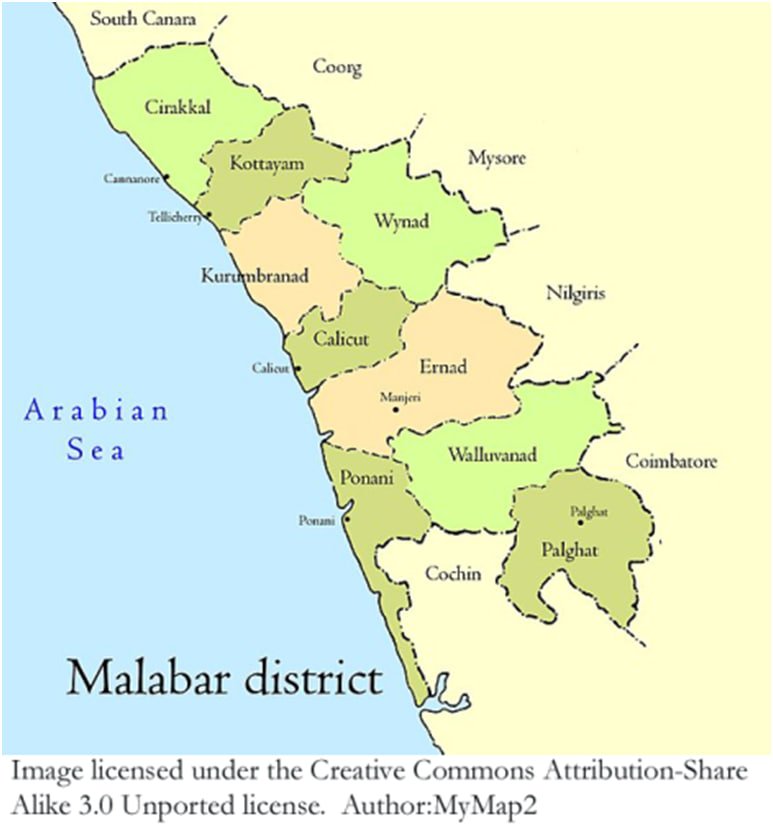

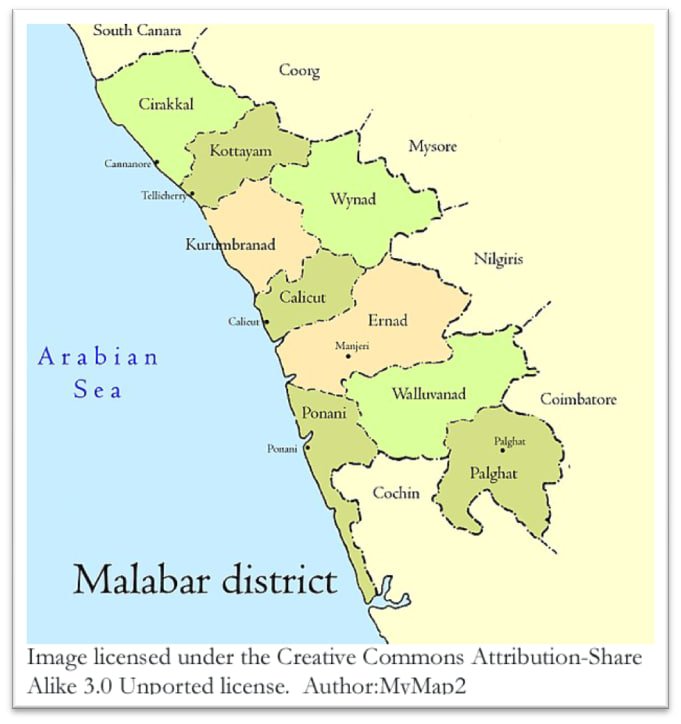

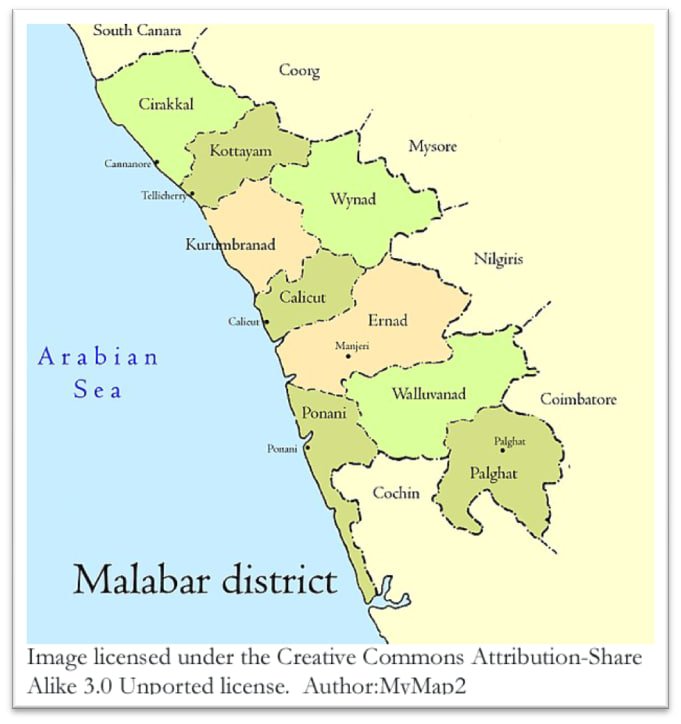

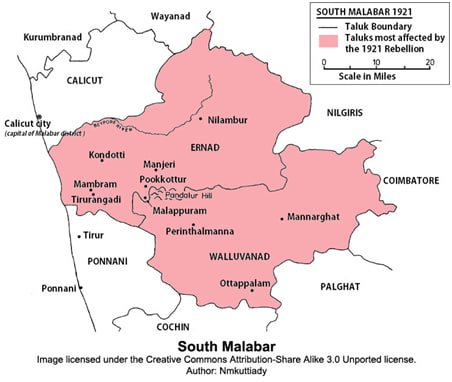

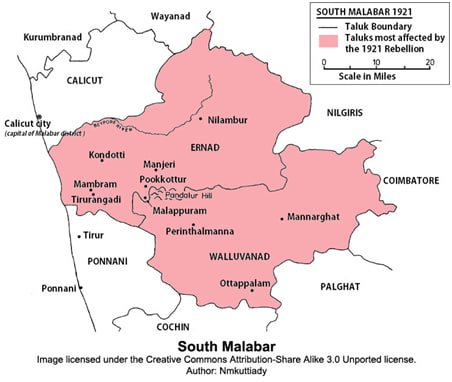

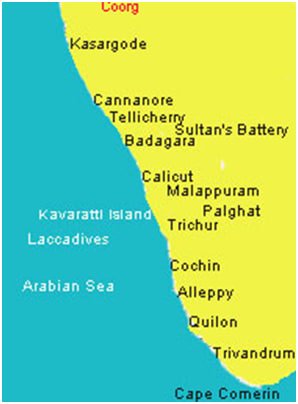

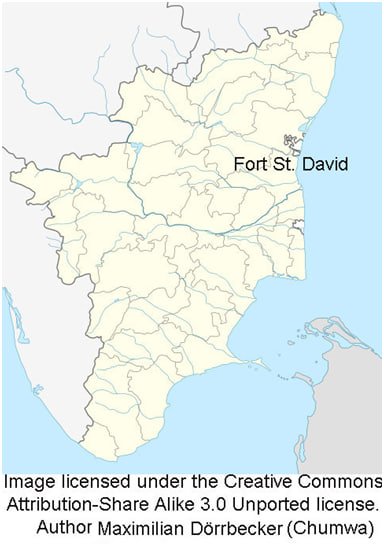

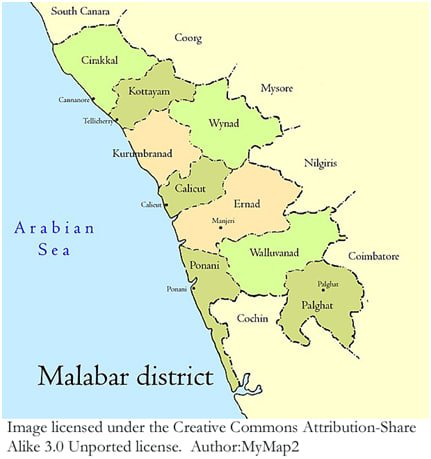

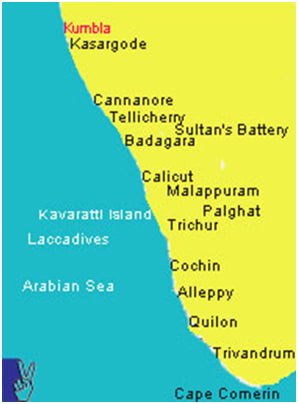

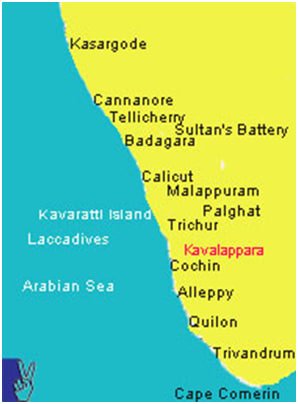

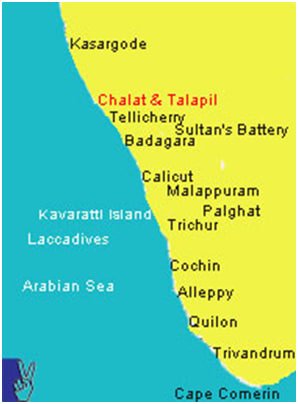

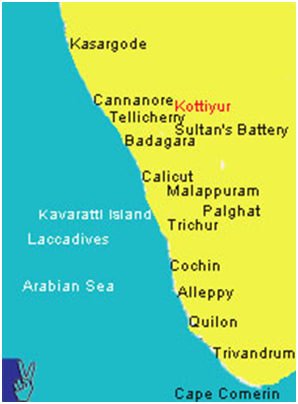

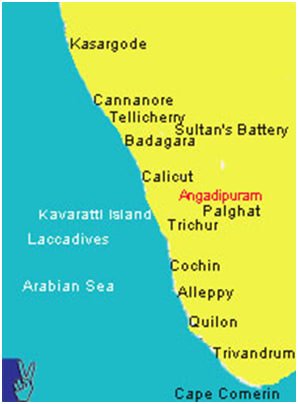

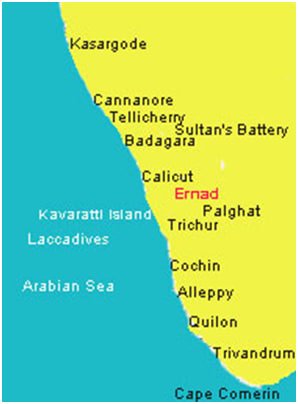

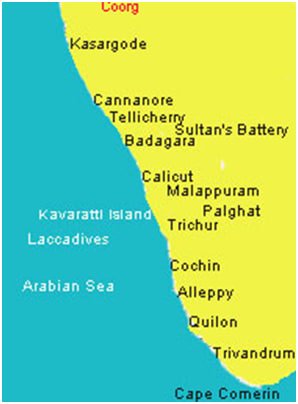

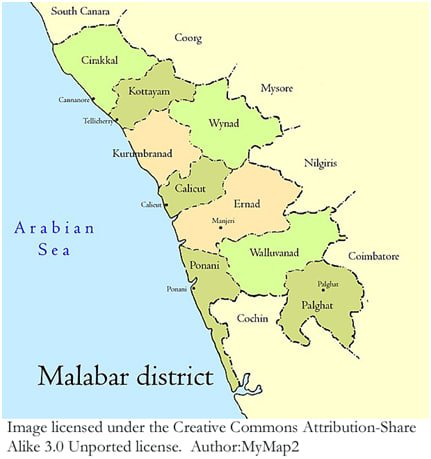

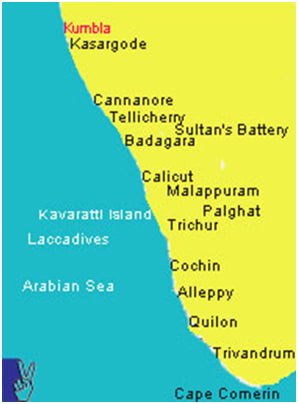

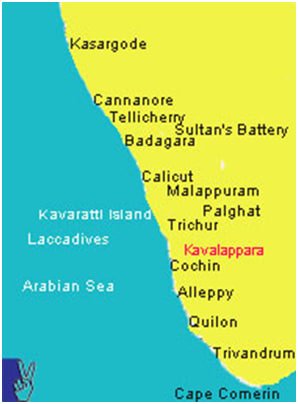

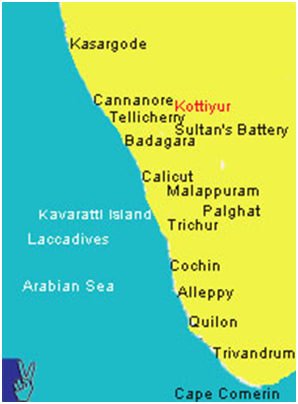

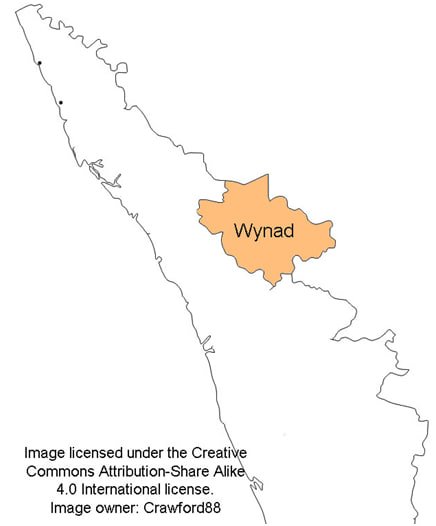

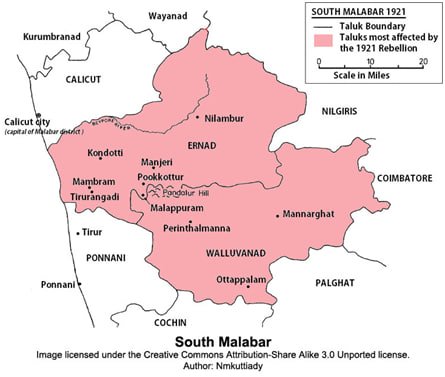

The contents of this book (Malabar by William Logan) are about a very miniscule geographical location inside the South Asian Subcontinent. The current-day geopolitical location of this place is the northern parts of the State of Kerala in South India. Even though the place was made into a single district by the English East India Company administration, as of now, the location has been divided into a number of small districts.

Beyond that, till around 1957, this location was a part of the Madras Presidency and then later on after the formation of India, a district of the Madras State. This location had only very minimal connection with the southern parts of current-day Kerala. However, on reading this book, one may not feel so. This book seems to have attempted to create a Kerala-feeling right from the middle of the 1800s. How this could come about should remain a mystery. However, on reading the book with some insights, one might be able to smell a rat. Actually there is more than one item in this book that gives a feeling that there is indeed something fishy about this book, and it’s very aspirations.

The digital copy of this book that came into my possession is the government of India printed version of 1951. It does claim to have made changes into place names to make them to be in sync with the modern names of the places. It seems a silly logic to doctor critical elements in a book of historical importance. Names are like the DNA codes in a genetic code string. A change in them can create so many changes in what the names stands for and what they signify. Connections and directions change.

It would be extremely silly to rename ancient cities with their modern names in history books. However, generally there is an attitude among formal academic historians to do as they please to please the modern political leaders of India. In fact, one can find words like India, Indians etc. cropping up in ancient and medieval histories of the subcontinent. Instead of saying the Moguls or the Rajputs had a fight with some other population group, words like: ‘Then the Indians attacked the Europeans’ &c. are frequently seen.

Beyond that, till around 1957, this location was a part of the Madras Presidency and then later on after the formation of India, a district of the Madras State. This location had only very minimal connection with the southern parts of current-day Kerala. However, on reading this book, one may not feel so. This book seems to have attempted to create a Kerala-feeling right from the middle of the 1800s. How this could come about should remain a mystery. However, on reading the book with some insights, one might be able to smell a rat. Actually there is more than one item in this book that gives a feeling that there is indeed something fishy about this book, and it’s very aspirations.

The digital copy of this book that came into my possession is the government of India printed version of 1951. It does claim to have made changes into place names to make them to be in sync with the modern names of the places. It seems a silly logic to doctor critical elements in a book of historical importance. Names are like the DNA codes in a genetic code string. A change in them can create so many changes in what the names stands for and what they signify. Connections and directions change.

It would be extremely silly to rename ancient cities with their modern names in history books. However, generally there is an attitude among formal academic historians to do as they please to please the modern political leaders of India. In fact, one can find words like India, Indians etc. cropping up in ancient and medieval histories of the subcontinent. Instead of saying the Moguls or the Rajputs had a fight with some other population group, words like: ‘Then the Indians attacked the Europeans’ &c. are frequently seen.

Last edited by VED on Fri Feb 16, 2024 12:20 pm, edited 3 times in total.

6, India and Indians

6 #

Since I have mentioned the words ‘India’ and ‘Indians’, I think I will say a few things about these words:

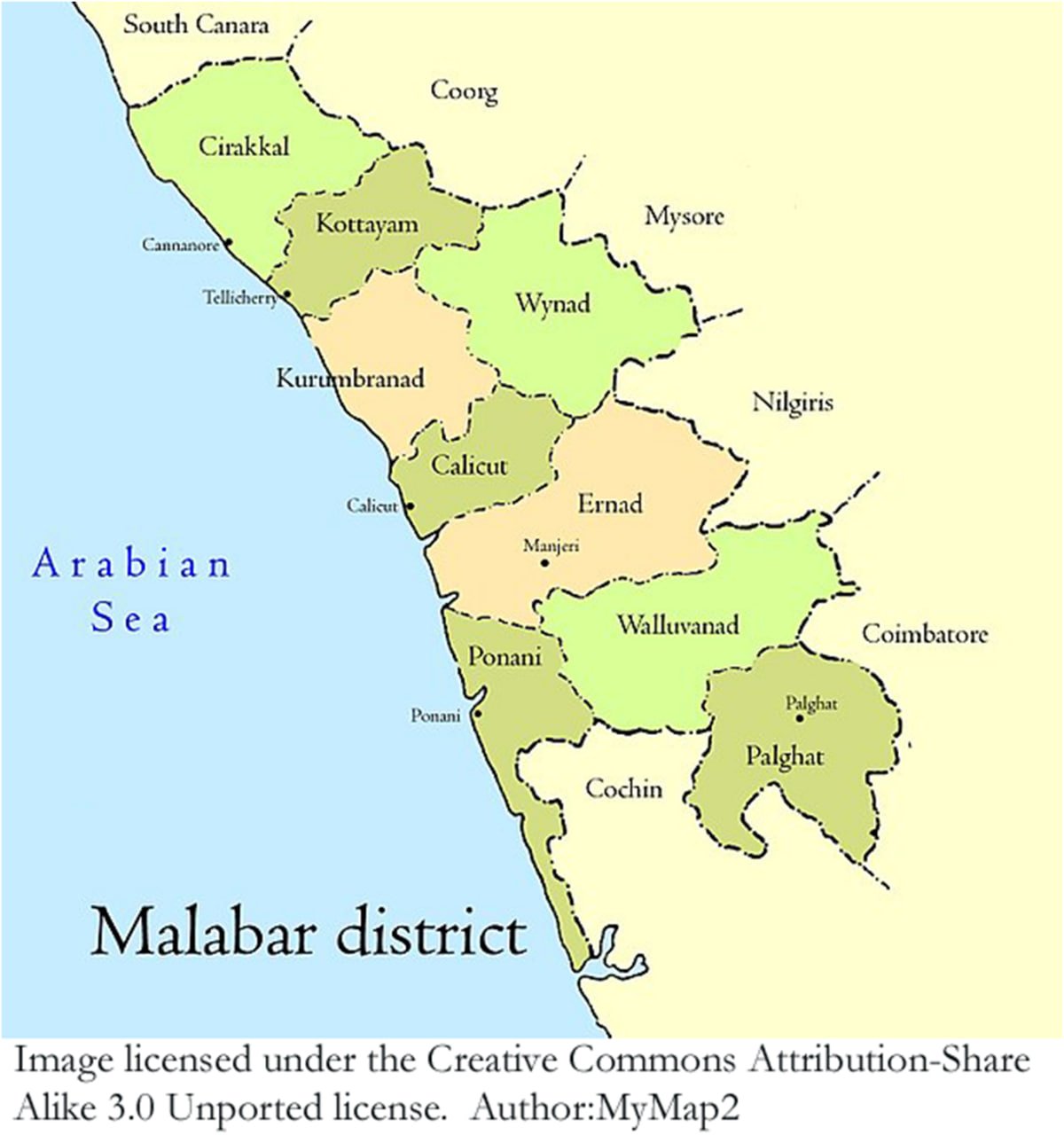

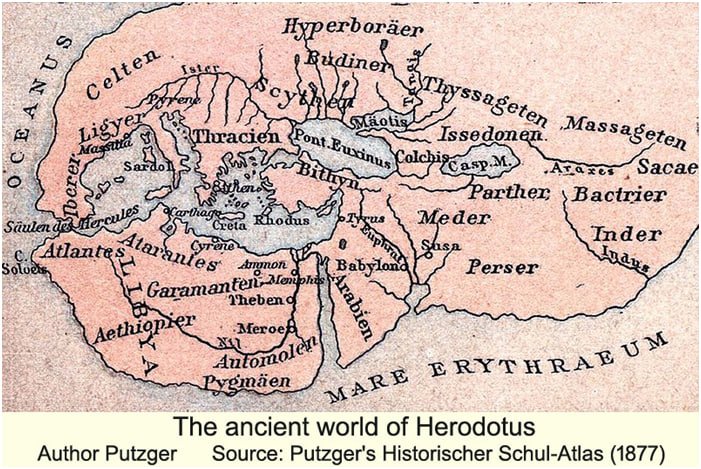

There was indeed a mention of a land which was commonly identified by the maritime traders and others from other locations as Indic, Inder, Indus, Indies etc. May be more.

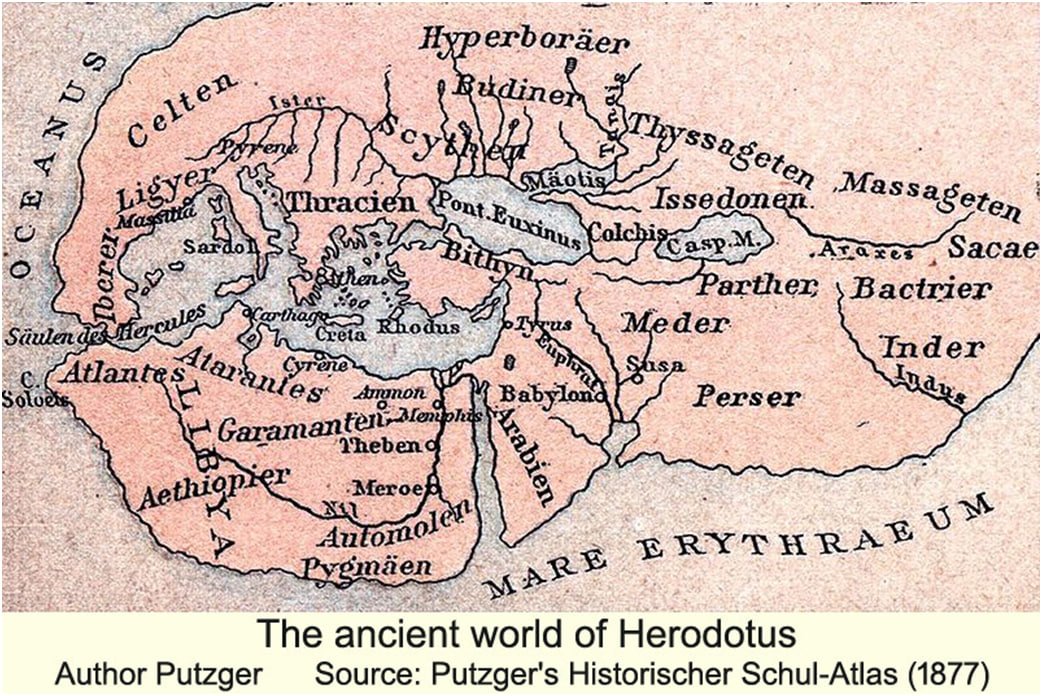

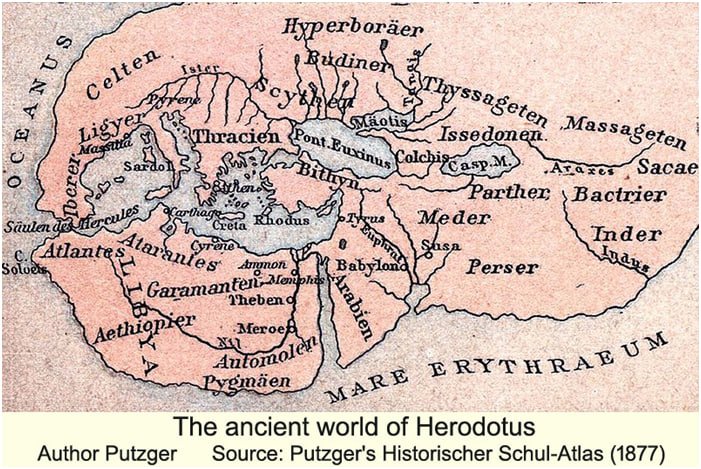

Even in the works of Herodotus the word Inder (Indus) is seen to come. It was some kind of remote location in the east from where certain merchandise like Pepper, spices, and many other things were bartered by the traders.

There was no historically known nation as 'India' inside the subcontinent. Even the joining up of the various kingdoms (some 2000 of them, small and big) as subordinates of the Hindi-speaking populations took place only in 1947. Pakistan also took a part of the Indus area and captured the various locations to form Pakistan.

In fact, Indus is in Pakistan and has not much to do with the south, east, or north-eastern parts of the subcontinent.

I do not know if the word 'India' is used in the Puranas, or epics such as Mahabharatha or Ramayana, or if either Sri Rama or Yudhishtar have claimed to be Indian kings. Also, whether such kings as Marthanda Varma, Akbar, Krishna Deva Raya, Karikala or Ashoka have claimed to the Indian kings.

The word 'India' and the location 'India' could be a creation mainly of Continental Europeans. May be the Arab traders, and the Phoenicians also must have used it to denote a trade location.

I feel that Continental Europeans did create four ‘Indias’.

But actually it is Indies; not Indias.

QUOTE: India, however, in those days and long afterwards meant a very large portion of the globe, and which of the Indies it was that Pantænus visited it is impossible to say with certainty ; for, about the fourth century, there were two Indias, Major and Minor. India Minor adjoined Persia. Sometime later there were three Indies — Major, Minor and Tertia. The first, India Major extended from Malabar indefinitely eastward. The second, India Minor embraced the Western Coast of India as far as, but not including, Malabar, and probably Sind, and possibly the Mekran Coast, India Tertia was Zanzibar in Africa. END OF QUOTE.

I think the author is actually talking about ‘Indies’ and not about ‘India’.

‘Major’, ‘Minor’ and ‘Tertia’ Indies had some connection to the subcontinent in parts. As to the fourth one they created, it was in the American continent. In the US, till around 1990, the word 'Indian' was found to connected to the native Red Indians.

The word ‘India’ I feel is like the Jana Gana Mana. Not pointing or focusing on to native-subcontinent origin. [Jana Gana Mana actually points to the Monarch of England in the sense that it had been first used to felicitate the King and Queen of England by none other than the Congress party, when it had been a party of England lovers.]

However, the historical nation connected to the word India is 'British-India' (not any of the ‘Indias’ mentioned above), and is a creation of England and not of Continental Europeans.

However, it did not contain the whole subcontinent. At best only the three Presidencies (Madras, Bombay and Calcutta) and a few other locations were inside it. The rest of the locations which are currently inside India, such as Kashmir, Travancore &c. were taken over under military intimidation or occupation.