13. When introduced to a new lifestyle

13. When introduced to a new lifestyle

Written by VED from VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS

Previous page - Next page

Previous page - Next page

Vol 1 to Vol 3 have been translated into English by me directly.

From Vol 4 onward, the translation has been done by a translation software. So there can be slight errors in the text.

It was slightly difficult to make the translation software to understand that in Indian languages, there are hierarchy of words everywhere.

From Vol 4 onward, the translation has been done by a translation software. So there can be slight errors in the text.

It was slightly difficult to make the translation software to understand that in Indian languages, there are hierarchy of words everywhere.

Last edited by VED on Sat Aug 09, 2025 12:42 pm, edited 4 times in total.

Contents

Contents

1. About the nairs who got degraded through their occupation

2. On the kalarippayattu expertise found among Nayars

3. The matter of great weapon skill and excessive bravery

4. Why the greatly courageous Nairs fled and hid

5. Like tall bamboo poles planted in the marshy region

6. Contradictory behaviours displayed by the Nairs

7. Barbaric tendencies displayed by local militia

8. Testimonies of excessive courage and remarkable virtue

9. Social reform as a major upheaval

10. The consequences of granting complete freedom to the lower castes

11. The words, thoughts, and opinions of the lower castes

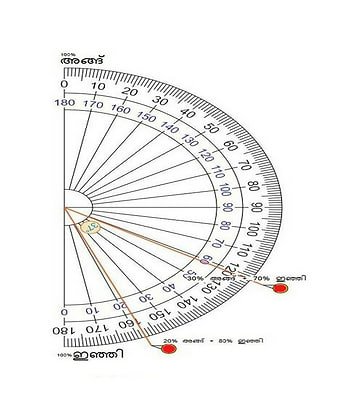

12. The ratio of two different directional components at opposite angles

13. About the enigmatic personality trait of the Indicant Index Number

14. When those enslaved in feudal languages receive an English experience

15. Social structure designing links upward and downward

16. On the breaking and redirection in IVRS

17. High-low status fragments that keep individuals apart

18. What saved the Nayars from harsh enslavement

19. Nayars did not leap out of Islam when given the chance

20. When introduced to a new lifestyle

21. On information that was immediately turned into private property

22. The motivation to convert others to one's own religion

23. Contradictions in Hindu-Muslim communal conflicts

24. When new laws began to curb old powers

25. A glimpse into the origins of the Mappila Rebellion in South Malabar

26. Social Changes in British Malabar

27. One of the factors that fuelled deep resentment toward Islam in this peninsula

28. A state requiring veils and sieved paper before the eyes

29. On the term “Mappila”

30. Historical background of the Arakkal family

31. About other Mappilas and another connection of the word Mappila

32. The matter of Valluvanad

33. Different communities within Malabar’s Muhammadans

34. About Mappila slave traders

35. To introduce and establish family and family prestige

36. About the Ahmadiyya movement and other matters

37. About cow worship

38. ome miscellaneous matters among Malabari Muslims

39. About tying the mundu to the left

40. Words among Malabari Muslims

41. More words among Malabari Muslims

42. Paradise, Houris and More

43. Malabari Muslims in the democratic surge

44. The mindset that only by uniting can one survive here

45. When the lower communities entered the Muhammadan label in Malabar

46. To import English human personalities into British-Malabar

47. The waves of the Khilafat Movement in Malabar

48. On filmmakers rewriting history

49. Matters just before the day one was born

50. Half-dark and clear as daylight

1. About the nairs who got degraded through their occupation

2. On the kalarippayattu expertise found among Nayars

3. The matter of great weapon skill and excessive bravery

4. Why the greatly courageous Nairs fled and hid

5. Like tall bamboo poles planted in the marshy region

6. Contradictory behaviours displayed by the Nairs

7. Barbaric tendencies displayed by local militia

8. Testimonies of excessive courage and remarkable virtue

9. Social reform as a major upheaval

10. The consequences of granting complete freedom to the lower castes

11. The words, thoughts, and opinions of the lower castes

12. The ratio of two different directional components at opposite angles

13. About the enigmatic personality trait of the Indicant Index Number

14. When those enslaved in feudal languages receive an English experience

15. Social structure designing links upward and downward

16. On the breaking and redirection in IVRS

17. High-low status fragments that keep individuals apart

18. What saved the Nayars from harsh enslavement

19. Nayars did not leap out of Islam when given the chance

20. When introduced to a new lifestyle

21. On information that was immediately turned into private property

22. The motivation to convert others to one's own religion

23. Contradictions in Hindu-Muslim communal conflicts

24. When new laws began to curb old powers

25. A glimpse into the origins of the Mappila Rebellion in South Malabar

26. Social Changes in British Malabar

27. One of the factors that fuelled deep resentment toward Islam in this peninsula

28. A state requiring veils and sieved paper before the eyes

29. On the term “Mappila”

30. Historical background of the Arakkal family

31. About other Mappilas and another connection of the word Mappila

32. The matter of Valluvanad

33. Different communities within Malabar’s Muhammadans

34. About Mappila slave traders

35. To introduce and establish family and family prestige

36. About the Ahmadiyya movement and other matters

37. About cow worship

38. ome miscellaneous matters among Malabari Muslims

39. About tying the mundu to the left

40. Words among Malabari Muslims

41. More words among Malabari Muslims

42. Paradise, Houris and More

43. Malabari Muslims in the democratic surge

44. The mindset that only by uniting can one survive here

45. When the lower communities entered the Muhammadan label in Malabar

46. To import English human personalities into British-Malabar

47. The waves of the Khilafat Movement in Malabar

48. On filmmakers rewriting history

49. Matters just before the day one was born

50. Half-dark and clear as daylight

Last edited by VED on Thu Jun 12, 2025 9:36 am, edited 8 times in total.

1. About the nairs who got degraded through their occupation

3. The third Nayar caste in Travancore is the Swarupam Nayars.

They are the servants of the Kshatriya families in Travancore. As they are positioned under the Namboodiris as servants of the Kshatriyas, they rank socially lower than the Illakkar Nayars.

In the feudal linguistic environment, even the work one does influences the language codes. This is a matter that requires particular attention. Without understanding this, the English today propagate the immature idea of social equality.

Among the Swarupam Nayars, there were those known regionally by different names. Kaippizha, Pattazhi, and Vembanad Swarupam Nayars fall into this group.

It should be remembered that below the Illakkar and Swarupam Nayars, there were numerous lower castes. Therefore, the language codes place the Swarupam Nayars above these lower castes.

It is written in Travancore State Manual Vol. 2 that Swarupam Nayars are equivalent to the Akattu-Chernna and Purattu-Chernna Nayars of English Malabar. One cannot overstate how intricate this information is.

QUOTE from TSM V2: The Swarupakkars correspond to the Akattu-Chernna and Purattu-Chernna Nayars of English Malabar. END OF QUOTE

As social details from English Malabar increasingly reached Travancore, each group in Travancore began identifying their counterparts in English Malabar during the period of English rule in Malabar.

For example, when the Ezhavas looked, they found their counterparts in the Thiyya caste of Malabar. It did not matter to them that there were two distinct Thiyya groups in Malabar. Their sentiment was likely, “Both are us.”

By establishing this connection, it became understood that among the Ezhavas, there were even ICS officers, the highest government officials in British-India. At the same time, in Travancore, they remained a slave caste.

4 & 5. Padamangalam and Tamil Padam Nayars

These are the fourth and fifth Nayar castes. It is written that they are not true Nayars and are migrants from Tamil regions to Travancore.

These claims are foolish because Travancore State Manual Vol. 1 states that Travancore is a region with Tamil heritage. Moreover, the social position of Nayars under the Namboodiris has existed since ancient times. Various castes likely entered this position, which is how the diverse Nayar subcategories were formed.

Those who provided information about Padamangalam and Tamil Padam Nayars, or those who documented them, may have had a slight mental distance from them.

It is claimed that these two groups of Tamil-heritage Nayars were distinctly different from other Nayars until some time ago. However, by the time Nagam Aiya’s book was published, this distinction may have faded.

The occupations of Padamangalam Nayars reportedly included sweeping temples, cleaning temples, and carrying lamps during spiritual processions.

It must be understood that Travancore is not like old England. Travancore has a language with strict landlord-slave relational codes. If the lower castes broke social boundaries and rose upward, Nayars performing such temple tasks would face significant social harm through linguistic codes.

Next, I will discuss the social relationships among these five Nayar groups in Travancore. Although they are all presented as Nayars above the lower castes, significant hierarchies exist among these five groups. However, clear boundaries for these distinctions may not exist.

This is because individuals and families within each group may rise or fall in different ways. Thus, even within a single group, one family may be kept distant while another from the same group may be brought closer.

It is said that one subgroup would not eat food cooked by another subgroup. Moreover, different subgroups would not sit in the same row to eat at public gatherings. Instead, different subgroups sat in different rows to eat.

Swarupam Nayars could eat food from Illakkar homes, but Illakkar women would not eat food from Swarupam homes.

However, it is generally stated that men from all subgroups would eat food from the homes of all subgroups, but women would not. This may be to maintain subtle yet strong mental boundaries created by feudal language codes.

For example, even if male police employees, from constables to non-IPS SPs, eat together at the same venue, the invisible hierarchies among them persist in that environment without any loss of strength.

However, if the wives and other women from their families sat together at the same venue, conversed, and ate, they might not maintain the same hierarchical positions as their husbands in the police department. This is because, in such a women’s gathering, positioning would be based on age, the status of their own occupations, and other such factors.

It should be remembered that the honorifics like “Chettan,” “Chechi,” “Sir,” and “Maadam” are indispensable codes that persist in all human interactions within feudal languages.

Returning to the Nayars of Travancore, in marital relationships, women would only marry men from higher subgroups or their own subgroup.

It is said that a woman marrying into a higher subgroup would not be allowed to freely enter the kitchen of her husband’s home.

In addition to the aforementioned high-ranking Nayars, there are also Idacherry (herdsmen), Maranmars, Chempotikal, Odathu Nayars, Kalamkottikal, Vattakkadans or Chekkalas (oil sellers), Pallichans (palanquin bearers), Asthikkurisshi Nayars, Chettikal (traders), Chaliyanmar (weavers), Veluthedanmar (washermen), and Vilakkithalavanmar (barbers), all of whom are Nayars. However, the higher Nayar subgroups consider them lower.

It is clearly stated in Travancore State Manual Vol. 2 that these groups were degraded due to their traditional occupations.

QUOTE: … their traditional occupations themselves being the cause of their degradation. END OF QUOTE

It must be understood that the English language cannot position a person or group as a distinct caste based on their occupation. The capabilities of feudal languages are profound indeed.

Last edited by VED on Thu Jun 12, 2025 4:18 am, edited 2 times in total.

2. On the kalarippayattu expertise found among Nayars

I will now examine some ancient writings that grandly praise the Nayars.

Before quoting them, I wish to remind the reader of one thing. The term "Nayar" may be a title that various distinct castes claimed and later regarded as their hereditary right.

It can be understood that when foreigners from outside South Asia came to Malabar in ancient times, they encountered Nayars skilled in martial arts. It is also understood that young members of certain Nayar households began training in kalarippayattu from around the age of seven.

The martial art system, practised in North Malabar and South Malabar, involved weapons such as swords, daggers, sticks, whips, knives, and kathara, along with shields to block such weapons, protect body parts, and conceal them. It included combat techniques, bare-handed fighting, locking body parts, methods to escape such locks, various flips and jumps, and complex footwork.

This martial art is called kalarippayattu.

It does not seem that such a tradition existed in Travancore in the same way. In Travancore’s Tamil linguistic heritage, martial arts like adithada, adimurai, and silambam, linked to Tamil traditions, may have been prevalent.

As mentioned earlier, Nayars migrated to Travancore from Malabar in ancient times. It is not unlikely that some among them brought kalarippayattu to Travancore. One thought is that Southern kalarippayattu might be a diluted form of Malabar’s kalarippayattu, though I am unsure if this is correct.

It has been noted earlier that temple-dwellers known as Nampikals, Nampyars, and Nampishanmar ran gymnasiums and physical training centres in Travancore, teaching swordsmanship and similar activities. However, it is unclear whether this was directly linked to Malabar’s kalarippayattu tradition. It seems that such arts were not unique to South Asia but were also practised by certain communities in other primitive regions worldwide, taught exclusively to their members.

It is said in Keralolpathi that Parashuraman brought kalarippayattu from elsewhere. Keralolpathi, as previously indicated, may have been written with specific hidden motives based on hearsay. It can be assumed that Parashuraman taught kalarippayattu to Brahmins. If he did so, it seems likely it occurred in Malabar.

When individuals were appointed as Nayars under Brahmins to perform protective duties, it can be inferred that this training shifted to them.

It appears that certain high-ranking Nayar families in North Malabar and South Malabar preserved these combat skills and martial techniques through daily practice and training over centuries. The venue for this was known as the kalarippayattu arena.

The kalarippayattu of Malabar, referred to as "kalarikkurikkal," likely involved a group of trainees demonstrating loyalty under a master teacher. This was a movement of individuals bound at opposite ends of the 180° spectrum of feudal language codes, such as "Oru" (highest he) and "Inhi" (lowest you).

However, all involved were likely from high-ranking Nayar families, meaning both the master and disciples were Nayars.

It is heard that the kalarippayattu arena was a long, pit-like space dug into the ground. I am unsure if this was the typical design of a kalarippayattu arena. Personally, I have imagined kalarippayattu arenas as long, ground-level structures covered with palm leaves.

Although it can be claimed that Nayars hereditarily preserved kalarippayattu, it is understood that some high-ranking families among the matrilineal Thiyyas in North Kerala also practised this art form. I believe there were families in my own familial connections that ran kalarippayattu arenas in ancient times. Close interactions with Nayars likely led some matrilineal Thiyya families to kalarippayattu expertise.

It is unknown whether the patrilineal Thiyyas of South Malabar had this training knowledge.

At the same time, a tradition of this practice is seen among Mappilas in both North and South Malabar. I lack further details on this.

One aspect related to Malabar’s kalarippayattu is padakali worship. It is unclear whether the Kali worship tradition is linked to Brahmin spirituality. I do not intend to delve deeper into this topic now.

In Travancore and Tamil Nadu, martial arts training likely began with devotion to a divine figure, as it seems people undertake such activities by pledging loyalty to a war deity. I have no further details on this.

It is unknown whether padakali worship was part of the kalarippayattu arenas run by matrilineal Thiyyas. The question arises whether Nayars were willing to share their deities along with kalarippayattu expertise.

It is unlikely that padakali worship was part of Mappila kalarippayattu training. I have no information on this either. However, a Muslim individual told me that before kalarippayattu training or performance, the practitioner touches the ground with their index finger as a sign of respect. I know no further details.

Although it is unclear how the seeds of kalarippayattu reached the Mappilas, it is said that the Kunjali Marakkar family, residing in Kottakkal near Badagara in North Malabar, had close ties and dealings with the Calicut royal family, which likely brought them into contact with kalarippayattu. However, it is worth noting that Kadathanad, near Badagara, is considered the birthplace of kalarippayattu. It does not seem necessary for the Kunjali family to have gone to Calicut in South Malabar to acquire kalarippayattu; their ties with the Kadathanad royal family and other local Nayar families would have sufficed.

It can be inferred from the Malabar Manual that some Mappilas in North Malabar had some form of physical training. It is recorded that certain Mappila boatmen who rowed trading boats were trained in “sword and target.”

QUOTE from Malabar Manual: These boats were found not to be of sufficient strength for the purpose, as they were unable to cope with the Mappila boats rowed by eight or ten men with four or six more to assist, all of whom (even the boatmen) practised with the “sword and target” at least. END OF QUOTE.

Although it is unclear what “sword and target” refers to, it may be linked to kalarippayattu.

Foreign traders and travellers may have been astonished by the skills of Nayars trained in kalarippayattu. This is evident in multiple writings by ancient foreigners.

For example, the Malabar Manual quotes lines about Nayars from Johnston’s Relations of the most famous Kingdom in the world (1611 Edition).

QUOTE:

At seven years of age they are put to school to learn the use of their weapons, where, to make them nimble and active, their Sinnewes and Joints are stretched by skilful fellows, and annointed with the Oyle Sesamus:

By this annointing they become so light and nimble that they will winde and turn their bodies as if they had no bones, casting them forward, backward, high and low, even to the astonishment of the beholders.

Their continual delight is in their weapon, persuading themselves that no nation goeth beyond them in skill and dexterity END OF QUOTE.

It must be understood that the person who wrote the above passage directly witnessed a kalarippayattu performance. Watching a high-quality kalarippayattu performance today could still reveal astonishing physical feats. However, much needs to be said about this, which I cannot cover in this writing.

Regarding the above quote, a few points can be made.

First, the concept of a Nayar “school.” Physical training was likely what was understood as “school” back then. There is no significant error in this, as it is far better than today’s system of confining children in classrooms and cramming their heads with useless information.

However, the question arises whether a purely physical curriculum would suffice. I won’t delve into that now.

Another point that struck me was the final sentence of the quote: the belief that no one in the world is better than them.

Other writings support this attitude. More details may follow in the next writing.

See also

3. The matter of great weapon skill and excessive bravery

In the previous writing, the reader might recall a sentence from Johnston’s Relations of the most famous Kingdom in the world (1611 Edition), quoted in the Malabar Manual.

QUOTE:

Their continual delight is in their weapon, ...

END OF QUOTE.

Reading this sentence might create a great impression on many. However, upon reflection, one can understand the reality of the frenzied life journey of these adolescents and young men.

This writer recalls, about forty years ago, attending a martial arts training session. The people who came for training were of various kinds. However, I did not meet anyone else there with a deep habit of reading English as a background. Yet, the atmosphere that was common to all and made everyone seem alike was the martial arts training environment.

The conversations mostly revolved around training-related bets, championships, brawls, street fights, and the like. Whatever was said, individuals would express it by lifting and lowering their hands, legs, and bodies, twisting and turning, and even performing in a theatrical manner with various gestures. They would display great joy, immense daring, profound worldly knowledge, and personal connections, conveying these to others through words or otherwise.

However, if one tries to evaluate these individuals, their social, familial, professional, and other aspects based on such behaviour, it could lead to the kind of folly seen in defining Nairs by relying on Johnston’s Relations of the most famous Kingdom in the world, resulting in shallow essay writing.

Another similar experience this writer had about thirty years ago in another state comes to mind. While briefly associating with some people involved in a film production setting, I had the chance to observe and experience something noteworthy.

Among this group was a person who was the brother of a superstar and an up-and-coming actor. Whenever this person spoke, he would act out the matter through physical gestures, almost spontaneously. On some occasions, the film dialogues he was memorising for camera performances would come out of his mouth in an acted tone.

In an ordinary social setting, such behaviour might evoke great amusement or raise questions about possible mental instability in the minds of onlookers.

To claim that all Nair families lived in such a mental atmosphere would be utter foolishness.

The reason is that even the highest among the Nairs were required to work in Namboodiri households. Yet, while working for Namboodiris and, moreover, controlling and suppressing various lower castes for the sake of the society they lived in, and even enslaving some from the lower castes, over time, some Nair families themselves became immensely wealthy, owned land, held significant social power, and developed physical and authoritative capabilities surpassing those of many Namboodiri families.

This is indeed a significant matter. It would be a nightmare for feudal language regions to have government peons with more wealth and social power than IAS officers, police constables with more wealth and social power than IPS officers, or soldiers with more wealth and social power than commissioned officers in the military. This topic may be elaborated on further later.

An incident related to the Nairs needs to be mentioned. I hope to cover it in the next few writings.

The Portuguese writer Duarte Barbosa, between approximately AD 1500 and 1516, recorded something about the Nairs in The Coasts of East Africa and Malabar (Hakluyt Society), p. 124:

QUOTE:

When they go anywhere they shout to the peasants, that they may get out of the way where they have to pass; and the peasants do so, and if they did not do it, the Nayrs might kill them without penalty.

END

This matter needs further clarification. The “farmers” Barbosa refers to may not actually be farmers. Instead, they could be enslaved Pulayas or other lower castes, treated like cattle, toiling daily under the scorching sun in the fields of landowners. The mention of “killing” them likely does not refer to a formal trial and execution but rather to cutting them down on the spot.

It seems that Nair men carried a sword when they went out, much like people carry mobile phones today. It doesn’t seem they carried the sword sheathed at the waist with a belt; rather, they likely held it in hand.

The Travancore State Manual Vol. 2 states:

QUOTE:

They invariably carried arms with them which consisted of swords, shields, bows, arrows, hand-grenades, &c.

END OF QUOTE

This matter should be understood with limitations. It is likely that only some Nairs carried such heavy and cumbersome loads daily. However, it can be inferred that some Nairs had the authority to carry such items.

Nevertheless, Nairs can only be compared to today’s police constables, not to IAS or IPS officers.

Nairs (Shudras) were not permitted to wear gold or silver ornaments. With the advent of English rule in Malabar, this restriction likely faded unnoticed. However, in Travancore, it was likely due to Col. Munro’s influence that this restriction was lifted in 1817.

From Travancore State Manual Vol. 1:

QUOTE:

The restriction put on the Sudras and others regarding the wearing of gold and silver ornaments was removed.

END

The true social status of Nairs can be discerned from this information. However, from the perspective of those below them, this might seem an unnecessary detail, much like how Indian auto drivers might view the status of police constables with sheer defiance.

Another point Barbosa noted is noteworthy:

QUOTE:

They have a belief among them that the woman who dies a virgin does not go to paradise.

END

Such a belief likely greatly facilitated the blending of Namboodiri blood into their family lineage through their women.

In the social context of that time, successfully pleasing Namboodiris through the women of the family might have been akin to passing Public Service Commission exams today to secure officer positions in government systems.

A change came when English rule took root in Malabar, and government officers began to be selected through competitive exams from those proficient in the English language.

During English rule, it is often claimed today, without hesitation, by many scholars on online platforms that the English indulged in using local women sexually and even enslaved them for this purpose. The reality was quite different.

It is stated in texts like the Malabar Manual, Travancore State Manual Vol. 2, and Malabar and Anjengo that Nairs were great warriors and highly courageous.

This may be somewhat true for some of them. Some Nairs likely achieved great proficiency in martial arts, and there may have been those among them who were unafraid to die displaying such skills.

However, gaining social prestige solely through the ability to hack and chase people is akin to today’s police system.

When English language education began to be provided in Malabar without caste discrimination, such physical prowess lost its value, as need not be specifically stated. Meanwhile, in Travancore, the London Missionary Society and others planned to topple, overturn, and uproot Nairs in a different way.

They provided immense knowledge to many from the lower castes, instilling great self-confidence and self-respect in them.

Native Life in Travancore notes:

QUOTE:

“To-day, when passing by your schoolroom, I heard the children sing their sweet and instructive lyrics with great delight. We Sudras, regarded as of high caste, are now becoming comparatively lower; while you, who were once so low, are being exalted through Christianity.

I fear,” he added, “Sudra children in the rural districts will soon be fit for nothing better than feeding cattle.”

END

If this continues, Shudra (Nair) children in rural areas will soon be fit only for tending cattle. END

However, it must be noted that in Travancore, the Christian missionary movement did not use the English language to uplift the lower castes, which remained a significant shortcoming.

At the same time, they likely relied on the address of the English administration in Madras for protection in Travancore.

4. Why the greatly courageous Nairs fled and hid

The French ethnographer Elie Reclus wrote a book titled Primitive Folk: Studies in Comparative Ethnology in the 1800s. A cursory glance through this book reveals several observations about the Nairs. It does not seem to be written based on direct knowledge. Rather, it feels as though it relies on accounts from other observers during the English colonial period. This is not certain.

The book appears to contain much about the Nairs based on superficial hearsay, yet it gives the impression that these are firsthand observations.

Some sentences from the book are as follows:

QUOTE:

All knew at least how to read and write, but the chief part of their education was carried on in the gymnasium and the fencing school, where they learnt to despise fatigue, to be careless of wounds and to show an indomitable courage, often bordering upon foolish temerity.

They went into battle almost naked, ...

Their extraordinary agility made them the terror of every combat in forest or jungle. On the smallest provocation they devoted themselves to death, and having done so, one would hold his ground against a hundred.

END

They went to battle almost entirely naked...

Their astonishing agility made them a terror in any forest or jungle combat. With the slightest provocation, they would commit to fighting to the death, and once engaged, one of them could stand against a hundred. END

It cannot be said that such seemingly exaggerated stories lack any truth. However, people from England, and indeed from continental Europe, who came to this semi-primitive region were likely astonished by many things. Yet, it is not certain they fully understood what they saw.

The lines quoted above from Primitive Folk are also cited in Travancore State Manual Vol. 2. This suggests that praises of the Nairs were collected from various sources.

Regarding the Nair warriors, Sir Hector Munro, a British military leader, made a remark recorded in the Malabar Manual:

QUOTE:

They were, in short, brave light troops, excelling in skirmishing, but their organisation into small bodies with discordant interests unfitted them to repel any serious invasion by an enemy even moderately well organised.

This is a profoundly insightful observation. However, it is unclear whether Sir Hector Munro understood the feudal language-based social structure that created this situation or the complex psychological effects it had on individuals.

This topic will need to be explored in greater depth later.

While military parades, camaraderie among soldiers, hierarchical officer ranks, and insignia were part of the English administration’s arsenal—qualities not taught in kalaris or most martial arts venues—it is understood that similar elements existed in the military systems of continental Europeans like the French, Dutch, Portuguese, Italians, and others.

Yet, in any confrontation, it was the English forces, with local warriors in their ranks, that ultimately emerged victorious.

It must be understood that even the English were unaware of the invisible software system working tirelessly behind the scenes to enable this consistent success.

This topic can be examined in greater depth later.

To emphasize the Nairs’ sense of superiority, Primitive Folk states:

QUOTE:

They felt themselves under the necessity of slaying, or perishing in the attempt to slay, every individual of inferior caste who took the liberty of touching or even breathing upon them.

END

However, it seems no one fully understood why such intense personal hostility arose in the Nairs.

Today, if an ordinary person in Kerala addresses a government official as Ningal (polite level, stature neutral You), a similar kind of personal hostility may arise in the official. However, it must be added that this mental disturbance is not exclusive to officials.

While Nair warriors in every village learned various martial arts and lived with loyalty and obedience to their teachers and masters, it is true that they eagerly sought to clash with Nair groups from neighbouring regions. It is also true that each small kingdom provided numerous opportunities for such conflicts.

The Travancore State Manual attests that every local ruler and royal family lived in constant insecurity. At any moment, they could be attacked by outsiders or even by their own people. The fundamental and practical political principle of the time was that the strongest ruled.

At the same time, the lower castes were not taken seriously. It is true that Nairs could cut them down. However, approaching the lower castes was itself an unpleasant task for the Nairs.

When the French in Mahé and the English administration in Malabar established police systems, Nairs and Marumakkathayam Thiyyas (north Malabar Thiyyas) likely joined as ordinary policemen. Taking a lower-caste person into custody for lawlessness might have felt like a terrifying task for the Nairs.

Some indications of this are found in Primitive Folk:

QUOTE:

Down to the present day, when the police give them plebeian prisoners to guard, it is amusing to see how afraid they are to go near them, thinking of nothing but how to keep their distance. One might almost think they feared their captives. They have been known to refuse battle to unworthy foes.

END

There have been instances where they refused to fight unworthy opponents. END

The feudal language codes fostered and nurtured this sense of repulsion and superiority in the Nairs. The reality is that even today, the English have little understanding of this.

During the invasions of Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan, in various parts of Malabar, when lower castes like Cherumars, Pulayas, and possibly Marumakkathayam Thiyyas attacked Hindus (Brahmins), their associated temple servants, Nairs, and their families in homes and streets, it is astonishing that the Nairs could neither fight back nor protect their revered Hindus, their families, or the women in their households.

Primitive Folk describes the Nairs as follows:

QUOTE:

They are the handsomest, most shapely, best proportioned men I ever saw. They are of a dusky olive colour, and all tall and lusty; moreover, they are the best soldiers in the world, bold and courageous, extremely skilful in the use of arms, with limbs so agile and supple that they can throw themselves into every imaginable posture, and thus avoid or cunningly parry every possible stroke, whilst at the same time they spring upon the foe.

END

Despite such descriptions, when Cherumars, Pulayas, and possibly Marumakkathayam Thiyyas attacked the homes and women of Hindus, their loyal temple servants, and Nairs, it seems no one has considered why the Nairs lost all their martial prowess.

It was previously mentioned that Karna, the mere son of a charioteer, challenged Prince Arjuna to a contest of archery skill.

Imagine, for a moment, that the ordinary people of modern England are the haughty Nairs. In such a scenario, when cricket teams from India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and elsewhere arrive in England to play against them, the English Nairs would abandon their homes and lands and flee—this is what history teaches us.

When the lower castes ran amok, what weakened the Nairs was:

Their repulsion toward the lower castes.

The lack of pride in boasting about defeating them.

As Sir Hector Munro noted, while Nairs individually possessed great weapon skills, agility, and acrobatics, they lacked the organised leadership and collective mindset to strategise and counterattack as a group.

This caused the Nairs to face numerous defeats, which can be detailed in the next writing. Additionally, there is another subtle factor to be addressed in the next piece.

While Nairs had the skill, weaponry, and social authority to cut down a lone Pulaya, the lower castes, casting aside their subservience and charging in groups, likely evoked the image of polluted water rushing toward them.

Another overlooked matter is why the lower castes could not organise to drive out those who treated them like cattle.

One characteristic of feudal languages is that they motivate individuals to place others in hierarchies, trample those below, and pull down those above. This insight could lead to many other complex details.

5. Like tall bamboo poles planted in the marshy region

Let us once again examine how the Nairs were described among primitive folk.

They are the handsomest, most shapely, best proportioned men I ever saw. They are of a dusky olive colour, and all tall and lusty; moreover, they are the best soldiers in the world, ...

Elie Reclus describes the Nairs as exceedingly handsome, tall in stature, and robust, as well as the fiercest warriors in the world.

This description may be 100% accurate for a small section of the Nairs. However, I can’t help but wonder if there’s a significant flaw in Elie Reclus writing an anthropological work based solely on this small group.

Although he was a Frenchman, it is understood that he migrated to England and settled there. Once in England, everything seems much simpler and more trivial to comprehend.

It’s akin to a Tamilian who goes to America today and becomes the CEO of a major company. In their homeland, they might not even dare mention a mere police constable by name, but upon reaching America, they might start to feel even the American President is insignificant.

I have no specific information about Elie Reclus. However, it seems that much of what he wrote in his book was based on observing only a tiny fraction of social realities.

For example, this is how the book introduces the Tiyas:

Tirs - Tayers, Tayars, or Chogans, Chagoouans, Chanars, servants, or demon-worshippers.

This is a description steeped in utter foolishness and entirely lacking depth.

Nevertheless, if one wishes, historical records could likely be found to prove this description accurate. The fluctuating depth and profundity of historical documents amassed by scholars can indeed be problematic.

Now, let us return to the Nairs.

Readers should note that there are many different groups among the Nairs. It is unclear which of these groups were associated with martial arts, and which regularly participated in attacks and counterattacks. However, it can be understood that a small percentage of young men from these groups likely ventured into martial arts from a very young age.

It’s worth noting that there would have been no intellectual pursuits, occupations, side jobs, or recreational activities available to them at the time. Their reading and writing skills would have been minimal. It’s also uncertain what books would have been available for them to read. Games like chess might have been known, but chess, too, is a form of combat-related recreation.

It’s like observing bulls. Imagine a Frenchman arriving in Malabar and seeing only the stud bulls.

Picture a stud bull standing tall, with robust physique, glistening muscles, great height, fine complexion, sprouting horns, and, to top it all, a vibrantly coloured weapon for sexual prowess, standing completely naked. Some cows rush towards it, while others flee and hide. If, after observing this bull, one concludes that all bulls in Malabar are like this and writes a treatise on bovine anthropology, consider the absurdity of such a narrative.

The other bulls in Malabar, with their nasal septums pierced and ropes tied through them, castrated, and toiling under the scorching sun in paddy fields until late in the day, live lives of sacrifice. A scholar fixated on stud bulls might not notice this reality.

Here, we are writing about a group of individuals who address the lower classes with terms like “Inhi,” “Eda,” “Edi,” “Avan,” “Aval,” or “Ayyaal,” possessing a mindset suited only for cutting them down if needed. These individuals have great weapon proficiency, physical agility, extensive training, and a sense of social and personal dominance.

Could such individuals unite as a group under a hierarchical leadership structure? It’s not unlikely that each person, defined as a “leader” in feudal terms, might nurture such an attitude.

It’s like the Indian army conducting parades on stages expected to draw global attention. For such parades, soldiers with highly polished and visually striking physical personas are specially groomed. Seeing them march with the precision of machinery in front of millions, it would be foolish to evaluate the entire Indian army based on them.

The reason is that those groomed for parades are not the ones who must crawl and slink through battlefields under their officers’ command, displaying great subservience.

In a feudal linguistic environment, the most effective superior-subordinate relationship is one where the superior is at a great height, and the subordinate is as subservient as possible.

This phenomenon can be observed among private doctors, lawyers, and others. A doctor might find it problematic to keep a subordinate who displays a personality so elevated that it could rival their own charisma.

In the Indian army, too, the most suitable soldiers for officers on battlefields may be those with the most submissive mindsets. Delving deeper into this topic is not possible now, as it is a profoundly complex issue. I hope to explore it later.

However, one more point can be made. This dynamic may pose a significant disadvantage for the Pakistani army, but delving into that now is also not feasible.

In general, it can be noted that only in pristine-English societies does a subordinate’s strong personality serve as a great asset in the superior-subordinate relationship.

During the English administration, government officers, doctors, and others exhibited a remarkable gentleness in their personalities.

The primary reason for this was the profound and radiant light of English literary tradition that had permeated them. Despite receiving meagre salaries and benefits, these individuals were capable of achieving great intellectual heights.

(Moreover, they worked under the English, who stood at great intellectual heights. It’s worth noting that the English language lacks the verbal codes in words like “You,” “He,” or “She” that degrade or suppress others.)

However, today, government officers, including police officers, academic scholars, military officers, and others, are elevated with sky-high salaries, benefits, and lofty titles. Without such elevation, most would display mere barren personalities and intellects. This, too, can be explored later.

Now, let us return to the matter of the Nairs.

Great financial security, astonishing physical agility, a mindset that views lower classes as mere cattle, and weapon proficiency elevate the personalities of martially skilled Nairs to the heavens.

Such personalities cannot be found among English soldiers, as even the most distinguished among them can only rise to the level of an ordinary Englishman.

Like tall bamboo poles planted in the marshy region, these Nair warriors stand.

If they were grouped with ordinary Nairs and sent to the battlefield, it’s possible to predict their level of success in advance.

However, it is also observed that Nairs with social authority, physical strength, and weapon proficiency developed significant domineering attitudes.

For example, in the Malabar Manual:

👉

…and the kuttam or assembly of the nad or county was a representative body of immense power which, when necessity existed, set at naught the authority of the Raja and punished his ministers when they did ‘unwarrantable acts.’

👉

These Nayars, being heads of the Calicut people, resemble the parliament, and do not obey the king’s dictates in all things, but chastise his ministers when they do unwarrantable acts.

In Travancore, the Travancore State Manual mentions a group called the “Arannoor”:

From the earliest times therefore down to the end of the eighteenth century the Nayar tara and nad organisation kept the country from oppression and tyranny on the part of the rulers, ...

Such Nair family assemblies likely limited the authority of the Namboodiris.

A similar development seems to have occurred in the Kerala Police Department. It appears that around the 1980s, the government permitted police personnel to form their own organisation.

Just as the Nair Arannoor family organisation was facilitated, possibly by the royal family to limit the Namboodiris’ authority, the Kerala Police organisation was permitted by a revolutionary political party, likely to curb the power of IPS officers.

This may have hindered maintaining strict discipline among lower-ranking police personnel. The only option left for IPS officers might be to dance along with the antics of their subordinates, gradually altering the dynamics.

As the Nairs gained organised strength, the control of Namboodiris, the king, and the royal family diminished.

A similar situation likely unfolds in the police department.

When the police department personnel were granted the facility to organise, I recall a young commissioned officer from the Indian army who visited my college at the time. He said:

You shouldn’t let these people (lowest him) organise. Once they do, they won’t listen to anything you say.

Imagine the scenario if Indian army soldiers were allowed to organise.

6. Contradictory behaviours displayed by the Nairs

The extraordinary courage and personal charisma inherent among the Nairs have already been discussed. What I am about to write may not be pleasing to some Nairs. However, it must be specifically noted that all communities mentioned in this writing have been addressed in the same manner—without bias or favour.

The loyalty to their sustenance, sense of duty, courage, and commitment traditionally upheld by the Nairs are exemplified by an account cited in the Malabar Manual from the historian Sheikh Zin-ud-din:

A quantity of cooked rice was spread before the king, and some three or four hundred persons came of their own accord and received each a small quantity of rice from the king’s own hands after he himself had eaten some. By eating of this rice they all engage to burn themselves on the day the king dies, or is slain, and they punctually fulfil their promise.

Such a pledge may not solely be an example of courage. It could also reflect the plight of individuals ensnared by societal linguistic codes. The reason historians have not recognised this is simply that the immense power of linguistic codes has not been subjected to serious study.

The tragic fate of the Japanese air force’s Kamikaze suicide squad pilots during the Second World War may have been shaped by the horrific codes embedded in the Japanese language, capable of trapping and binding both humans and animals. These pilots, some as young as teenagers, flew bomb-laden planes with no possibility of returning alive, crashing with precise intent into British and American warships.

Many individuals in Nair families may have been caught in such societal traps. Family members might have had significant interests in directing their kin towards death, as the aura of heroic sacrifice allowed the family to shine in society.

This is similar to how every incident glorifying police bravery today creates immense admiration among the lower classes, justifying their presence. Additionally, reducing the number of family members could conveniently limit those with claims to family property.

Young Nairs likely had few other pastimes or amusements. In each small region, engaging in duels, slashing, and killing each other was probably the common strategy among Nair youths to maintain a revered status in the hearts of the lower classes.

While toiling in paddy fields, the lower classes would sing songs that included the names of those who died in such conflicts.

However, it seems unlikely that prominent individuals from elite Nair families were eager to sacrifice their lives in this manner. Typically, they did not have to participate in daily warfare. Instead, they could send lower-ranking family members to fight.

But when the battlefield encroached upon their own lands, turning their fields into war zones, these Nairs had no choice but to enter the fray. What did they do then?

As Germany, with its formidable weaponry and military might, conquered much of continental Europe and prepared to invade England—a mere 20 kilometres across the sea—it seemed an easy task to transport their army across. England had only a nominal military presence, and any resistance could be crushed by German warplanes.

Yet, England’s centuries-old civil defence system rose again. Young men, middle-aged individuals, and even the elderly took to the streets. “Come on Harry, Come on Jack, Come on Baker, Come on Mr. Fraser,” they rallied, uniting, conducting makeshift military drills, setting up camps on high coastal cliffs, and monitoring the sea and sky 24 hours a day through binoculars. They relayed precise details of German military movements to English army centres.

Such social cohesion is a rare quality, found in the unadulterated English society.

The Nairs of Malabar, Travancore, and Cochin could not behave in this manner, as their societal language was a rigid feudal one.

Now, we must examine specific incidents. One could start with the arrival of the Portuguese in Calicut, but that would lead us deep into the annals of history, and there’s still a long way to go before writing history.

Thus, I will highlight a few incidents to illustrate instances where the Nairs’ personal courage faltered.

The reason for documenting such incidents is the excessive glorification of the Nairs’ traditional grandeur found in many writings. In reality, the Nairs were merely victims of the local feudal language. They, too, could not act beyond the dictates and designs of its codes.

Let us first look at Travancore, noting that Tamil Nairs were also present there.

From the Travancore State Manual:

Yet the Princes were not satisfied on the day. When Rodriguez with twenty-seven of his people laid the foundation stone, about two thousand Nayars collected there and tried to oppose them. But Rodriguez not minding raised one wall and apprehending a fight the next day mounted two of his big guns. The sight of these guns frightened the Nayars and they retreated.

Now, from the Malabar Manual:

But the Portuguese artillery again proved completely effective, and the enemy was driven back with heavy loss notwithstanding that the Cochin Nayers (five hundred men) had fled at the first alarm.

…it was with the utmost difficulty repulsed, the Cochin Nayars having again proved faithless.

.The fort was accordingly abandoned and it is said that the last man to leave it set fire to a train of gunpowder which killed many of the Nayars and Moors, who in hopes of plunder flocked into the fort directly it was abandoned

From the Travancore State Manual:

Meanwhile the subsidiary force at Quilon was engaged in several actions with the Nayar troops. But as soon as they heard of the fall of the Aramboly lines, the Nayars losing all hopes of success dispersed in various directions.

7. Barbaric tendencies displayed by local militia

It should not be assumed that the Nairs remained uniform in character across centuries.

On one hand, there were concerns about new groups entering Nair ranks in various small kingdoms. On another, different levels of Namboodiri families viewed them as subordinates. Additionally, beneath the Nairs were various strata of lower classes, many of whom may not have accepted their subservient status.

Some members of each Nair subgroup likely led ordinary lives, engaging in regular occupations without involvement in armed conflicts. Meanwhile, some young Nairs perished in duels or skirmishes, or lived with permanent injuries, such as lost limbs.

The Malabar Manual notes:

…or the Nayar militia were very fickle, and flocked to the standard of the man who was fittest to command and who treated them the most considerately.

This description applies not only to the Nairs but to all feudal-language communities.

However, the Malabar Manual also highlights that the Nairs embodied various barbaric tendencies prevalent in the semi-primitive region. Many of those they clashed with in daily life were likely rough characters. Yet, there is no doubt that any group—however gentle or less skilled in arms—who fell into their hands would be socially crushed by the Nairs.

Despite claims of great military prowess, it can be said that the Nairs lacked even a trace of the English sensibilities associated with such ideals. They harboured intense enmity and hostility toward defeated enemies and did not honour surrender agreements.

Consider this incident:

A large body (300) of the enemy, after giving up their arms and while proceeding to Cannanore, were barbarously massacred by the Nayars.

A continuation of this incident:

Captain Lane reported, ‘cruelly—shamefully—and in violation of all laws divine and humane, most barbarously butchered’ by the Nayars, notwithstanding the exertions of the English officers to save them.

A similar incident occurred toward the end of the Second World War, which will be discussed in the next section.

In an agreement made on 8 January 1784 between the English and the Bibi of the Ali Raja family (Arakkal family) in Cannanore Town, one of the Bibi’s key demands was protection from the Nairs.

This was not unique to the Nairs. Across this subcontinent, under English rule, it was common for surrendered groups to be slaughtered like stray dogs. Notably, Tipu Sultan’s forces treated their enemies—regardless of their community—with similar harshness.

From an English perspective, the evident inferiority of the Nair soldiers is mentioned in Chapter 80 of Part 3 of this text.

When Hyder Ali and later Sultan Tipu targeted Malabar and Travancore with a series of attacks, while some Nairs displayed great personal courage, collectively they exhibited defeat, flight, confusion, and disarray.

Consider the following excerpts:

“Fullarton applied for and received four battalions of Travancore sepoys, which he despatched to the place to help the Zamorin to hold it till further assistance could arrive, but before the succour arrived, the Zamorin’s force despairing of support had abandoned the place and retired into the mountains. Tippu’s forces, thereupon, speedily reoccupied all the south of Malabar as far as the Kota river.”

“Nayres were busied in attempting to oppose the infantry, who pretended to be on the point of passing over. They were frightened at the sudden appearance of the cavalry and fled with the utmost precipitation and disorder without making any other defence but that of discharging a few cannon which they were too much intimidated to point properly.”

“The whole army in consequence moved to attack the retrenchment; but the enemy perceiving that Hyder’s troops had stormed their outpost, and catching the affright of the fugitives, fled from their camp with disorder and precipitation.”

“The Travancore commander had arranged that the Raja’s force should reassemble upon the Vypeen Island, but the extreme consternation caused by the loss of their vaunted lines had upset this arrangement, and the whole of the force had dispersed for refuge into the jungles or had retreated to the south.”

“On this application Hyder Ali sent a force under his brother-in-law, Muckh doom Sahib, who drove back the Zamorin’s Nayars.”

The same group that astonished foreign travellers with their remarkable agility and weapon proficiency also displayed moments of trembling fear, as cited above.

However, it does not seem that many Nair warriors lacked personal courage entirely. For example:

“The Nayars, in their despair, defended such small posts as they possessed most bravely.”

“The Nayars defended themselves until they were tired of the confinement, and then leaping over the abbatis and cutting through the three lines with astonishing rapidity, they gained the woods before the enemy had recovered from their surprise.” (Wilks’ History, I, 201.)

Yet, such personal courage did not translate into collective strength or power for the Nairs. When enemies from Mysore, with more sophisticated social communication networks, arrived, the Nairs’ small acts of bravery could not function cohesively.

Another intriguing incident occurred during a clash with the Portuguese:

“But a partial crossing was effected at another point, and a curious incident, possible only in Indian warfare, occurred, for a band of Cherumar, who were there busy working in the fields, plucked up courage, seized their spades and attacked the men who had crossed. These being, more afraid of being polluted by the too near approach of the low-caste men than by death at the hands of Pacheco’s men, fled precipitately. Pacheco expressed strong admiration of the Cherumars’ courage and wished to have them raised to the rank of Nayars. He was much astonished when told that this could not be done.”

End

8. Testimonies of excessive courage and remarkable virtue

Quote: “A similar incident occurred towards the end of the Second World War, which will be discussed in the next section.” End of Quote.

This was mentioned in the previous section. I intend to elaborate on it here before moving forward.

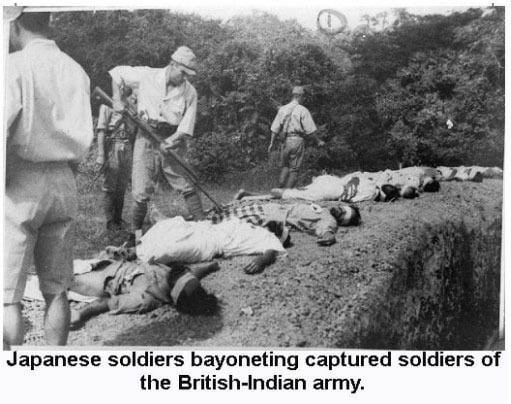

During the Second World War, the German government provided substantial funds to Subhas Chandra Bose’s movement to persuade captured British-Indian soldiers to switch allegiance and join their cause. Many British-Indian soldiers captured by Japanese forces did defect, primarily because being held in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps was akin to falling into the hands of wild beasts.

Subhas Chandra Bose and his associates formed the Indian National Army (INA), into which the Japanese incorporated these defectors. Historical records from that period suggest the INA had around 2,000 members, though modern estimates claim numbers in the tens of thousands.

Many Indian prisoners of war refused to defect. According to Japanese war archives, some were brutally killed by Japanese soldiers using bayonets. Refer to the image provided above.

Among British-Indian soldiers, intense resentment grew towards those who defected and fought against the English alliance. Towards the war’s end, when the English forces captured Singapore from the Japanese, these defectors were among those who surrendered. The English army took them as prisoners and assigned British-Indian soldiers to guard them.

However, in the absence of English officers, British-Indian soldiers attacked these defectors, slashing and bayoneting them, and attempting to kill them. They hurled insults like “Eda, blackleg,” during the assault. English troops had to intervene to protect these prisoners from the British-Indian soldiers.

Explaining in English the phenomenon where feudal languages inherently define a surrendered individual in degrading terms, leading to a 180-degree shift in human behaviour and attitudes, is indeed challenging.

Now, let us return to the Nairs.

In the Malabar Manual, there seems to be an inclination to heap praise on the Nairs at every opportunity. For instance, consider these lines:

“And probably the frantic fanatical rush of the Mappillas on British bayonets, which is not even yet a thing of the past, is the latest development of this ancient custom of the Nayars.”

This is merely an example of attempting to paint the Nairs’ legacy with grand courage through sheer nonsense and folly. The Mappillas mentioned here were lower-class individuals who converted to Islam, not Nairs who changed their religion, which is highly unlikely.

Between 1836 and 1853, the Malabar Manual records around 27 incidents in South Malabar where Mappillas attacked Hindus, their subservient Nairs, temple functionaries, and even, on one occasion, their enslaved individuals. Additionally, there is an account from North Malabar, in Kottayam Taluk’s Mattannur, where Mappillas stormed the home of a prominent landlord and massacred around 18 family members.

None of these incidents were driven by opposition to English rule. However, since the English Company governed and felt responsible for preventing anarchy, each incident led to police action and punitive measures by the English administration.

Further details related to these incidents will be addressed when discussing the Mappillas later.

It is evident that local elite families had an interest in misrepresenting English rule to the Mappillas. This is hinted at in the quoted passage above. The term “British bayonets” is unlikely to be William Logan’s own phrasing.

It was a common practice among the subcontinent’s elite communities to deliberately misrepresent English rule to various groups, fostering enmity to pit them against the English and exploit both sides for their own gain. This practice continues today.

On this note, I feel compelled to add another observation.

While the Malabar Manual repeatedly extols the Nairs as immensely courageous, actual accounts consistently show their courage faltering. However, there is a passage, clearly in William Logan’s words, that praises a group for displaying remarkable courage. This group, from South Malabar, was the lower-class Mappillas. Their excessive courage was attributed at the time to extreme religious faith and associated fanaticism.

However, the reality was likely more complex, a topic I won’t delve into now.

Another section of the Malabar Manual highly praises a different Muslim group (not Mappillas), bestowing upon them a certificate of virtue unmatched by any other community in this subcontinent, including Muslims. That discussion, too, cannot be addressed here.

End

9. Social reform as a major upheaval

The English administration in Malabar gradually took hold, impacting various Nair sub-groups to varying degrees, both minor and significant.

The introduction of written laws, a police force, and, moreover, the perception of all citizens as equals with the same rights and legal protections likely felt like a major upheaval for the Nairs.

Consider the situation where modern commercial vehicle workers are treated as equals to police constables within police stations, in terms of verbal codes and dignity, under the administrative system. The social reforms of the English administration were likely perceived by the Nairs and others, through their foresight, as a similar social upheaval.

Traditionally, Nair families and their actions were fully protected by the Namboodiri and local ruling families in each region. If a Nair assaulted, attacked, or harassed lower-caste individuals, there was no societal notion that such acts constituted lawlessness or warranted punishment.

The situation was akin to the Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act, 1990, in present-day Kashmir, where army officers have legal immunity for their actions. There can be no prosecution, suit, or any other legal proceeding against anyone acting under that law. Nor is the government’s judgment on why an area is deemed disturbed subject to judicial review.

Similarly, no matter what Nairs did, the lower castes had no right to question them, and the lower castes themselves firmly believed this. However, this did not mean Nairs could act with complete impunity.

The lower castes likely feared other lower-caste individuals the most. Protection for themselves, their families, and their women was typically ensured by the Nairs.

The Malabar Manual does not record any instances of Nairs cutting down or killing lower-caste individuals (excluding lower-caste Mappilas). The most precise reason for this may be that, under the English administration, only a few individuals, such as the Malabar District Collector, were English or British.

Until a cadre of directly recruited, English-educated local officers developed, the administration relied on local influential families in villages and small towns to govern. These families were invariably Nairs or higher castes.

Many of these families, individually or collectively, engaged in deceiving and misleading the District Collector and the English administration for personal or communal interests, manipulating official matters, committing fraud, and, where possible, engaging in corruption.

This is explicitly recorded by William Logan in the Malabar Manual.

Even if Nair families killed or harmed lower-caste individuals on agricultural lands or fields under their supervision, such incidents were unlikely to reach the higher echelons of the English administration. However, if the English administration became aware of such crimes and sought to address them legally, those responsible might today be recorded in formal history as Indian freedom fighters without hesitation.

Such killings reportedly continued, albeit to a lesser extent and as isolated incidents, in various rural areas even after India’s independence.

At the same time, in South Malabar, some Mappilas attacked certain Nairs, Ambalavasis, and Namboodiris in isolated incidents. Socially, these would be comparable to attacks on police or other officials today.

The English officers at the top of the administration at the time could not ignore such incidents.

There is much to say about the administration of that period, but that will not be covered now.

The English administration’s provision of education, English proficiency, and government job opportunities beyond caste hierarchies to lower-caste individuals further weakened the Nairs, who had long suffered from internal disunity.

It is difficult to gauge the complexity of what is being conveyed.

Lord William Bentinck noted in 1804, as recorded in the Malabar Manual, that Malabar’s inhabitants had a sense of independence of mind, unlike, for example, Tamils. Many English officers reportedly agreed that Malabaris possessed this independent mindset. The Malabar Manual, possibly a carefully curated document by Nairs, reflects this.

👉:

Lord William Bentinck wrote in 1804 that there was one point in regard to the character of the inhabitants of Malabar, on which all authorities, however diametrically opposed to each other on other points, agreed, and that was with regard to the “independence of mind” of the inhabitants.

At that time, the term “Malabari” referred to Nairs and higher castes up to Namboodiris, with Nairs likely being the most numerous. It is plausible that Nairs exhibited this independence of mind, likely shaped by the interaction of local feudal linguistic codes.

This raises the question: if so, weren’t feudal languages prevalent across the subcontinent, and shouldn’t this mindset be visible in everyone? The answer is that feudal languages indeed influenced everyone across the subcontinent. However, the specific codes within each region’s language and social systems interacted to create distinct and precise human behaviours.

Delving deeper into this topic is not possible here, but it can be noted that much may be uncovered in the intricate software-like codes of words and scripts. For example, in computers, English and other scripts can be written using Alt codes, a simple system unknown to many users. Similarly, different words in the same language may have distinct underlying software-like coding.

During this writing, an observation came to mind: writing “Nair” refers to an individual Nair, but writing “Theeyar” does not refer to an individual Theeya. Exploring terms like Theeyan, Theeyar, Theeyanmar, and Theeyarmar may reveal hidden linguistic nuances. The term “Theeyathi” could also be studied.

Terms like “Nayarthi” or “Nayarichi” were not tolerated by any Nair groups. Moreover, Namboodiri, Ambalavasi, and Nair sub-groups ensured their women were protected from such derogatory terms by establishing respectful terminology, promoting it, and enforcing it among lower castes, as noted earlier in this text.

The writing has veered from the intended topic. I plan to address the original point in the next piece.

10. The consequences of granting complete freedom to the lower castes

Let me revisit the point mentioned at the end of the previous writing.

Words like Namboodiri, Bhattathiri, Pattar, Chakyar, Nambiar, Variar, and Nair refer to individuals from specific social groups in Malabar, positioned above Theeyars in the social hierarchy.

Now, consider words like Theeyan, Malayan, Vannaan, Pulayan, Cheruman, and Pariyan (Pariah). These words, used to refer to those defined as lower castes, typically end with the script 'ൻ' (n).

This point is presented simply here, as it is a somewhat complex topic. For instance, take the word Brahmanan. It also ends with 'ൻ', yet a Brahmanan is not considered a lower caste.

However, the word Brahmanan does not seem to be commonly used to refer to an individual Namboodiri. It might merely be the Malayalam form of the Sanskrit word Brahman, which adds another layer of complexity.

This issue reportedly caused a problem among the Theeyars in North Malabar. The higher echelons among the Theeyars disliked the term Theeyan. Some claimed they were not Theeyars but Vaishyas instead, preferring to be addressed as Theeyar. Thus, a statement like “A Theeyan is coming” could transform into “Vaishyas are coming,” leading to a profound shift in personal identity.

This observation leads to a revelation: in modern Kerala, a new social group called “saar” is emerging through government positions. If this continues, within a few centuries, they could become a major social force. Within decades, government jobs may largely become hereditary family assets, without any doubt.

Beneath them, a group of “duplicate saars” may emerge and eventually fade away, driven by wealth and private-sector job titles.

In Malabar and Malayalam, the social dignity conferred by words ending in 'ര്' (r), like thiri, contrasts with the lack of dignity implied by words ending in 'ൻ' (n). The English administration was aware of this, as it is discussed in the Malabar Manual in connection with the word Oru (highest-level he/she).

Consider the distinction between Avaru (highest-level he/she) and Avan/Onu (lowest-level he) in Malabari, both translating to “he” in English. When the script ends with 'ര്', it denotes dignity; when it ends with 'ൻ', it implies a lack thereof.

In English, the words he and she have tails pointing upward or downward, a curious linguistic feature. However, there seems to be no recognition that this represents a form of subtle, almost sinister coding.

To understand this coding, one would need to delve into the intricate software-like codes of the Malayalam language, a path that seems obscure today.

Now, returning to the Nairs’ independence of mind: Nairs were subordinate to Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Ambalavasis, serving them loyally. To draw a simple analogy, they were akin to servants in a large household.

Typically, such servants, both male and female, live suppressed under the weight of feudal language and its verbal codes, shaping their mental and personal identity.

However, if a large group of impoverished people depends on this household, interacting with and pledging loyalty to these servants, the dynamics shift significantly. These impoverished people express subservience daily to the servants, not just the masters.

In feudal language, receiving such respect elevates a person’s dignity and personality, creating a transformation that is both sinister and divinely radiant. This implies that even the sinister carries a negative divine brilliance.

While these servants show great respect and subservience to the master and mistress of the house, they display an air of grandeur before outsiders. They cannot be easily equated with other household servants and refuse to be subdued. To others, this appears as an independent, almost arrogant mindset.

A key feature of feudal language is that when a subordinate individual receives respect, a subtle or significant shift in their social position occurs within the “design view” of the language’s intricate software-like structure.

In simpler terms, if someone previously addressed as Nee (lowest you), Eda/Edi (pejorative you), or by their bare name is suddenly called saar, Chettan (elder brother), Angu (highest you), Avaru (highest he/she), or Adheham (highest he) in another context, or is shown respect through non-verbal signals—such as loosening a mundu, standing in deference, offering a seat, or saluting with folded hands—their mental state undergoes a profound transformation.

These experiences challenge the servant’s lowly status as a worker. Superiors handle this in two ways:

Prevent servants from receiving such experiences that create duality in their personality. In the Indian military, this is somewhat enforced by limiting direct public subservience to lower-ranking soldiers. If soldiers in their 40s or 50s were constantly addressed as Saab, Memsahib, or Aap (highest you) by the public, younger officers might struggle to address them by their bare names or as Nee (lowest you), as the soldiers’ mindset would shift.

In contrast, this issue exists in the Indian police. As new constables interact with the public and receive daily subservience, they develop a sense of superiority. This, among other factors, reduces the control and authority of senior officers, who often overlook such behaviour, adopting a “see no evil, hear no evil” approach. They may excuse it as “no harm done” and avoid enforcing discipline to maintain this dynamic.

The police system established by the English administration in Malabar bears little resemblance to today’s police force.

Returning to the Nairs: in Malabar and Travancore, the Nair social position existed below Namboodiris and Ambalavasis. Various communities were likely appointed to this role. Whether equivalent positions existed elsewhere in the subcontinent is unclear.

However, English writers noted, as mentioned earlier, that only in Nepal was a similar social system observed, where Brahmins offered their women to Nairs, enabling the latter to maintain social superiority. Elsewhere, such practices would have led to social decline, but Namboodiris and certain Nair sub-groups strategically implemented this within strict rules, achieving social elevation.

The most critical rule was suppressing the lower castes. Without this, granting them complete freedom would likely lead to chaos—lower castes might line the streets, jeering, laughing, or even assaulting Nair women as they passed.

Things would have spiralled out of control.

In feudal language societies, unlike English societies, the suppressed must be kept in fear. For example, during Indian military officers’ get-together parties, soldiers stand guard like statues, and such events are held away from the gaze of ordinary citizens.

I plan to explore more on police, military, and related topics through the lens of linguistic codes in future writings.

Initially, Nairs were likely seen by Namboodiris as their servants. Over time, this perception changed significantly. Similar shifts are slowly occurring in today’s police force, where even the lowest ranks are now considered “officers.” These officers are the “saars” at the bottom of the police hierarchy, with the non-“saar” public beneath them. This is how feudal languages shape society.

I still haven’t reached the main point intended in the previous writing. I hope to address it in the next piece.

11. The words, thoughts, and opinions of the lower castes

It seems that the English administration did not fully grasp the true rationale, justification, or encouragement behind the social custom allowing Nair women to form short-term relationships with Namboodiris.

However, the broader truth is that many aspects of feudal language were beyond their understanding.

Nairs were the lowest rung within a vast, interconnected web of social groups—whose names did not end in the script 'ൻ' (n)—sharing various social privileges. Even among Nairs, there were prominent individuals and elite families.

For communities outside this web, whose caste names ended in 'ൻ'—such as Eezhavan, Chovvan, Arayan, Vedan, Mala Arayan, Kuravan, Kanikkaran, Pulayan, and Pariyan (Pariah)—they had no right to analyse, criticise, discuss, evaluate, judge, or morally assess the behaviours of higher castes, their internal hierarchies, or their subservience within this social structure.

This was also true in Travancore, where many communities with names ending in 'ൻ', outside the Brahmin-Ambalavasi-Nair alliance, existed, though this hardly needs stating.

The Nairs themselves faced an issue with the 'ൻ' suffix. Defining them as Shudran could evoke a similar problem, akin to the Theeyan-Vaishya distinction. This likely caused the Nairs some discomfort, however slight.