15. When looking broadly at the Mappila Rebellion

15. When looking broadly at the Mappila Rebellion

Written by VED from VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS

Previous page - Next page

Previous page - Next page

Vol 1 to Vol 3 have been translated into English by me directly.

From Vol 4 onward, the translation has been done by a translation software. So there can be slight errors in the text.

It was slightly difficult to make the translation software to understand that in Indian languages, there are hierarchy of words everywhere.

From Vol 4 onward, the translation has been done by a translation software. So there can be slight errors in the text.

It was slightly difficult to make the translation software to understand that in Indian languages, there are hierarchy of words everywhere.

Last edited by VED on Sat Aug 09, 2025 12:43 pm, edited 4 times in total.

Contents

1. About those who held the middle ground while setting both sides ablaze

2. Pledging allegiance to Hindi imperialism being defined as freedom

3. Back to the flow of the writing

4. Hindus and Muslims then

5. If one could point out a common enemy

6. Explosive social mechanisms in society

7. Insights from contradictory pieces of information

8. The English Company and its direct administration

9. Indication of an intolerable tyrannical rule

10. Confrontations through degrading verbal codes

11. Within a 15-mile radius of Pandalur Hill

12. The backdrop of Hindu-Mappila communal tensions

13. A mindset that persisted like a disease

14. The mindset of "We are the protectors of Islam"

15. Those who rush forward, conflating rage with religious fervour

16. A language that fosters invisible mental conflicts like a web of moss

17. Through the perspective of the elite of that time

18. The diverse Mappilas of Malabar and varying perspectives about them

19. The character of a great rogue

20. Matters differing from the mindset of the English administration

21. Viewing local elites in two distinct ways

22. On bearing the weight of a boulder through mere words

23. On inadvertently aligning with the Brahmin faction’s motives and actions

24. A social reform that led society to an explosion

25. Evil local customs and practices with no paths for reform

26. The truth no one is interested in telling

27. A social reality that may seem intolerable

28. Something more terrifying than a social upheaval

29. A measure implemented without any profit motive

30. Slavery without any influence of the English language

31. Slavery in an English language environment

32. Slavery eradicated in a land interested in maintaining it

33. Language determines social structure and communication pathways

34. Discovery that officials gain social power

35. Experiences incompatible with a new personality

36. Those who witnessed their traditional spiritual movement being stolen

37. Serious errors and limitations prevailing in England

38. Brutality standing at opposite corners

39. When nobles become destitute, a language system that prevents even stepping out of the house

40. The resurgence of the eradicated extortion system

41. On receiving high-level mental training

42. Respect that fades when the others improve in knowledge

43. The nature of commercial movements aligns with the linguistic culture of the people

44. Great things brought by English rule to British-India

45. List of educational initiatives launched by the English East India Company in British-India

46. The beginning of the end to the daily miseries faced by the people

47. A great wall against value degradation

48. Initiating numerous welfare state projects despite various oppositions

49. The bewilderment of the traditional elite Mappilas

50. Social complexities behind the Mappila Rebellion

2. Pledging allegiance to Hindi imperialism being defined as freedom

3. Back to the flow of the writing

4. Hindus and Muslims then

5. If one could point out a common enemy

6. Explosive social mechanisms in society

7. Insights from contradictory pieces of information

8. The English Company and its direct administration

9. Indication of an intolerable tyrannical rule

10. Confrontations through degrading verbal codes

11. Within a 15-mile radius of Pandalur Hill

12. The backdrop of Hindu-Mappila communal tensions

13. A mindset that persisted like a disease

14. The mindset of "We are the protectors of Islam"

15. Those who rush forward, conflating rage with religious fervour

16. A language that fosters invisible mental conflicts like a web of moss

17. Through the perspective of the elite of that time

18. The diverse Mappilas of Malabar and varying perspectives about them

19. The character of a great rogue

20. Matters differing from the mindset of the English administration

21. Viewing local elites in two distinct ways

22. On bearing the weight of a boulder through mere words

23. On inadvertently aligning with the Brahmin faction’s motives and actions

24. A social reform that led society to an explosion

25. Evil local customs and practices with no paths for reform

26. The truth no one is interested in telling

27. A social reality that may seem intolerable

28. Something more terrifying than a social upheaval

29. A measure implemented without any profit motive

30. Slavery without any influence of the English language

31. Slavery in an English language environment

32. Slavery eradicated in a land interested in maintaining it

33. Language determines social structure and communication pathways

34. Discovery that officials gain social power

35. Experiences incompatible with a new personality

36. Those who witnessed their traditional spiritual movement being stolen

37. Serious errors and limitations prevailing in England

38. Brutality standing at opposite corners

39. When nobles become destitute, a language system that prevents even stepping out of the house

40. The resurgence of the eradicated extortion system

41. On receiving high-level mental training

42. Respect that fades when the others improve in knowledge

43. The nature of commercial movements aligns with the linguistic culture of the people

44. Great things brought by English rule to British-India

45. List of educational initiatives launched by the English East India Company in British-India

46. The beginning of the end to the daily miseries faced by the people

47. A great wall against value degradation

48. Initiating numerous welfare state projects despite various oppositions

49. The bewilderment of the traditional elite Mappilas

50. Social complexities behind the Mappila Rebellion

Last edited by VED on Tue Jun 17, 2025 7:08 am, edited 7 times in total.

1. About those who had to hold the middle ground while setting both sides ablaze

In India, historical writing today is centred on the nation-state of India as it exists now. In this way, anything can be written relatively.

For example, with the notion that we are sitting at the centre of the universe, we can measure and interpret the movements, speeds, and other attributes of all other objects in the universe relatively. However, all the information we obtain may only be true within the frame of reference of Earth. If we move away from Earth, all the measurements, directions, speeds, and so forth that we have obtained may become meaningless.

Similarly, the study of history in India today is much the same. A nation merely a few decades old has taken possession of the entire past of South Asia. It is highly unlikely that those who lived in the diverse regions of ancient South Asia would have proudly declared themselves as Indians.

If, in the future, several new countries emerge in this region that do not exist today, all the historical studies constructed by India today would become meaningless.

This raises a question in my mind: is this the way history should be written and studied?

I won’t delve further into this topic.

However, the inspiration to write this came from the emotional response I felt upon reading about Sayyid Fazal in certain places. There seems to be an attempt to re-establish him as an Indian freedom fighter or a philosophical leader of the freedom struggle, or something of that sort—a futile endeavour, in my view.

During the time Sayyid Fazal lived, India as a nation did not exist. Moreover, it seems that even British India had not fully taken shape. The English Company, and later the English administration, was gradually building a nation here at that time.

Although scholars repeatedly claim that Sayyid Fazal fought against English colonial rule, in reality, his focus was on the traditional ruling class that had existed in South Malabar for generations.

Mappila farmers and other tenants had no direct means or pathway to convey their grievances to English officials. Any information about them or their concerns reached the English officials only through the traditional authorities—prominent officials in their administrative system or members of landlord families.

Replacing these authorities with lower-class individuals as officials would disrupt the entire social order without yielding any benefit. This is because, in feudal linguistic regions, governance must be conducted through individuals capable of controlling society. For this, a person must be invested with some form of elite status or title.

Even today, this remains a reality. In many instances in Malabar, the government uses individuals with the title “Mash” (teacher) behind their names to mobilise and control people for various purposes in certain regions. If individuals with common names like Kanaran or Kittan were placed in such informal leadership roles, no one would pay attention to them.

For English officials, directly engaging with the intricacies of society was indeed challenging. This is because local individuals are interconnected through terms like inhi, ningal, onu, olu, oru, olu, eda, edi, chettan, chechi, aniyan, aniyathi, chekan, and pennu. If English officials were to get entangled in this complex web of personal relationships, they too would end up using these terms and getting caught in their dynamics. This would tarnish their English image entirely.

Even today, this is a social reality. Those at the top stand above and apart from the lower-level personal relationship networks. If they were to behave without boundaries towards those at the lower levels, as is possible in English, they would lose respect without gaining any benefit.

It appears that many English officials recognised that South Asian societies have a certain impermeable nature.

Not only Mappila tenants but also non-Muhammadan tenants, farmers, and others had grievances they wished to convey to the English administration. However, they had to bypass the traditional ruling families and landlord families, who held them down like a heavy woollen blanket, to reach the English officials. I have come across indications of two distinct incidents where they attempted to do so.

I will discuss those incidents later.

Now, let’s turn to Sayyid Fazal.

He was a person of pure Arab lineage. Therefore, the local feudal linguistic terms could not harm him beyond a certain extent. However, it was generally understood among the lower-class Mappilas that such terms should not be used towards individuals of the Thangal status among Muhammadans.

I had previously mentioned that Sayyid Fazal instructed lower-class Mappilas not to address Nairs as ningal. This matter, when written in English, loses its explosive impact.

Furthermore, it is said that during a sermon or similar occasion, he stated that killing landlords who unjustly evicted tenants was a virtuous act. It was reportedly C. Kanaran, the Deputy Collector of Malabar, who informed the English officials of this statement by Sayyid Fazal.

This C. Kanaran, possibly known as Churayil Kanaran or something similar, seems to have been a member of the Thiyya community. When this individual joined the English administrative system, higher-caste officials in the administration provided him with the facility to sit on the floor in the office.

Once, when Henry Conolly, the Malabar District Collector, visited the Tellicherry Sub-Divisional Office for official purposes, he found this officer sitting on the floor while working. Immediately, Conolly ordered that a chair and a desk be provided for him to work.

Various forms of personal animosities existed within the local society. The English administration had to rise above all of this.

Although C. Kanaran experienced such derogatory treatment from higher-caste groups, it is likely that he developed personal relationships with socially elite Brahmin groups, landlords, and authorities.

Whether Sayyid Fazal actually said that landlords who evicted tenants should be killed is a matter that requires some scrutiny. It is possible that such a story was fabricated by lower-class Mappilas or, alternatively, by Brahmin factions.

The reason is that Sayyid Fazal gave lower-class Mappilas an instruction far more dangerous than planning a killing. That is, he told them not to address Nairs as ningal. In other words, he created a social pit into which Nairs and their families, including women, could fall to the level of inhi or ijji.

A plan to kill can be thwarted with armed force. However, there is no effective defence against being socially lowered through verbal codes, except perhaps a counterattack with weapons.

Sayyid Fazal also gave Mappilas instructions for other bold attack strategies, which were entirely non-violent in nature. Yet, these non-violent strategies were of a kind that could provoke even someone hailed by the media as the father of modern India to become violent.

The Nairs had no choice but to drive him out. They cannot be blamed either, for they too needed to live with their heads held high in the land.

However, it was the English administration that had the power to expel Sayyid Fazal.

The Brahmin faction had to set both sides ablaze while holding the middle ground to get things done. If the English were invaders, Sayyid Fazal was an invader too.

Among the Mappilas, Makkathayam Thiyyas, Marumakkathayam Thiyyas, and many other communities, there are bloodlines tied to invaders.

Last edited by VED on Sun Jun 15, 2025 11:35 am, edited 2 times in total.

2. Pledging allegiance to Hindi imperialism being defined as freedom

When reflecting on the violent acts of Mappila or Muhammadan lower-class individuals, it becomes necessary to consider social and political revolutions.

Let’s think about the freedom struggle of Palestinians today. It seems their language is Arabic.

It appears there are hardly any Indians or other speakers of feudal languages in Palestine.

The point about the presence of feudal language speakers is this:

If feudal language speakers are present, they would influence the Arabic language as well. Moreover, they might, to some extent, distort that language. This is merely a conjecture, as I do not know Arabic.

Nevertheless, when Arabic encounters individuals who are mentally elevated or trapped in a social hierarchy within its linguistic codes, the natural word codes of that language might experience a certain inadequacy. Furthermore, these individuals might also define the Arabic people, potentially causing subtle emotional shifts among them. This, in turn, could alter the linguistic word codes.

Now, regarding the Palestinians: if their language were like feudal languages such as Malayalam, Tamil, or Hindi, their people would not be able to stand united in resistance. Even if they could, their efforts would quickly fragment into various groups.

Moreover, if their homes were destroyed in Israeli attacks, individuals would face difficulties even communicating with one another. This is because, in the feudal linguistic communication mentioned earlier, the prestige of a house is a significant factor. If a house is reduced to rubble, the individual’s status in verbal codes also crumbles.

While it is true that Islam fosters a sense of unity among the people there, keeping Arabic linguistic codes intact, it must also be noted that most other Islamic nations have responded with indifference to the Palestinian issue.

When Clement Attlee handed over British India to the Nehru faction, and that group attempted to establish a Hindi imperialism in this subcontinent, socially elite individuals across British India scrambled and rushed to secure positions in the new administrative system, leaving others in their regions behind.

To put it more clearly, it should have been evident to anyone with some discernment in British Malabar that this region had never, in its history, been under Hindi rule. Furthermore, even Sanskrit words were scarcely present in the Malabari language.

At the same time, it is worth mentioning that Sanskrit words in most South Asian languages were only recently incorporated. If these Sanskrit words were removed from the languages of this subcontinent, the very concept of India as it exists today would lose its potency.

The local language is not one that enables Malabaris to organise or cooperate with one another. However, aligning under the leadership of political figures from the northern regions of the subcontinent could create an artificial sense of unity. This is what brought British Malabar under the fold of Hindi imperialism.

I won’t delve into a deeper analysis of this topic here. However, I will draw some points from this to the issue of Mappila violence in Malabar, though they may not be entirely applicable to Malabar.

Consider this:

The Mysorean invasions provided many lower-class individuals an opportunity to escape their cattle-like enslaved conditions. Many of them converted to Islam.

With this, significant social and personal elevation began to emerge among many of them. The infusion of fair-skinned Arab lineage also started to take hold. Since the English administration was established, the Brahmin-aligned Nair overlords could not suppress them.

Although the administration was English, English individuals were hardly visible in society. In other words, society continued to function under Brahmin dominance and Nair oversight.

The enslaved people, who had been treated as cattle for generations, could not organise themselves. The most significant reason for this was the feudal language prevalent in the region.

The feudal language, spoken by all, constantly encourages respecting those above, insulting and degrading those alongside, belittling them, viewing them with envy, and backstabbing them.

It must be understood that, to a large extent, Islam succeeded in countering the destructive mechanism of this local feudal language, which, despite its capacity to create great beauty through songs, is highly damaging.

In other words, without Islam, if these lower-class individuals tried to rise socially, they would clash among themselves from the outset. They would view each other with suspicion, fear, and envy, engage in slander, fight over seducing each other’s women, and ultimately collapse socially.

In their folk songs, they would sing and revel in the heroic tales of their Nair overlords. If anyone among them spoke disparagingly about Brahmin overlords or their women, many would eagerly rush to inform their Nair overlords about it.

It was Islam that brought a profound sense of brotherhood, cooperative mindset, and unity to such a people.

This is indeed a remarkable achievement. For instance, imagine if the Brahmin religion had acted similarly.

Suppose they taught their enslaved people their cherished spiritual traditions, allowed them to use the names of elite Brahmin individuals, and so forth. Consider what would happen if Brahmins gave opportunities to communities that sat and slept on the ground in filthy places like garbage heaps to enter homes, sit on chairs, discuss profound philosophical matters, and address or refer to people in their own households. Do not forget that the language is feudal in nature.

Even today, in most Indian households, no one would allow their kitchen maid to sit on a chair.

If such permission were granted, everyone knows that some form of impurity would enter the household.

At the same time, English officials in the English Company likely did not fully grasp the significance of this. They wouldn’t understand why someone who sweeps should not be given a seat. Moreover, in their own homeland, they themselves engage in all kinds of work.

However, even they could not seat Malabar’s lower-class individuals on chairs. If they did, the elite individuals of Malabar would not enter their establishments.

If the Brahmin faction allowed lower-class individuals into their traditional spiritual movement, the Brahmin movement would become tainted. Furthermore, Brahmins would lose all their traditional privileges. The lower-class individuals who entered would drive them out and degrade them in verbal codes.

Moreover, the Brahmin religion itself would become corrupted, potentially turning into a rogue religion of brawlers and troublemakers.

This is indeed a plausible reality.

From this perspective, Islam’s effort to uplift the lower classes is a monumental achievement. Upon reflection, it might even cause trepidation in many.

For a long time, Islam among Malabar’s Mappilas may have taken on a fearsome form, beyond its inherent qualities. It is easy to define this as the terror of Islam. However, the reality is as mentioned above.

The mere acquisition of fair-skinned Arab lineage and Islamic spiritual training among the uplifted lower classes did not bring peace to society.

On the contrary, it only intensified the terror unleashed by the feudal language in society.

Mappilas are not the only ones living in this society. There also exists a traditional hierarchical social structure.

The organised lower-class Mappilas harbour various grievances and animosities. If they begin to live and work in society without adhering to its traditional customs, it would indeed cause significant unrest among other communities.

The non-Muslim lower classes, who did not convert to Islam, would view these new Mappilas with great resentment and fear. This is because, with each passing generation, a significant transformation would be evident among the lower-class Mappilas. The awareness that they belong to the old lower-class lineage would begin to fade.

This is a problem for Nairs as well. They hold certain social oversight privileges, which they carry as part of their dignity. However, these new Mappilas are a group that disregards them.

The local language is not like English. Every word inevitably carries either subservience or its opposite, arrogance. Subservience is perceived as respect, while arrogance is seen as aggression.

This cannot be ignored or unheard. Those with eyes and ears will react and respond to the codes of these words.

The English faction has also uplifted lower-class individuals in various parts of the world, but in a different way. By teaching and encouraging the use of the English language, individuals naturally become liberated from the enslavement of local feudal languages. English words typically do not evoke pain, opposition, or provocation in others. (However, there is more to say on this, perhaps at a later time.)

Islam could not achieve this. However, what it did achieve is monumental. Yet, it created another fearsome situation in society, and the root cause of this must be identified.

3. Back to the flow of writing

It seems the last piece was posted in May 2021. Today is 18ᵗʰ November.

The topic being written about then was the historical event known as the Mappila Rebellion in South Malabar. At that time, ideas flowed into my mind like a stream. But now, looking within, I see no trace of that stream.

I’ve even forgotten what I intended to write about back then.

Still, I’m trying to climb back into the flow of writing.

I do not know how local Islamic scholars understood the Mappila Rebellion. However, I have before me some writings submitted as doctoral theses.

One major flaw in these writings seems to be that the thesis scholars have failed to recognise the most brilliant idea of Islam—or, if not Islam, then of Muhammad—which is the vision of granting individuals, both socially and personally, an elevated and egalitarian personality and dignity.

Another is the complete lack of awareness about the existence of the monstrous entity that is the feudal language within the local social environment.

Moreover, there appears to be a general shortcoming in the inability to understand or approach the magnificent historical phenomenon of the English administration in Malabar and across South Asia from a higher perspective.

Many seem intent on evaluating the English administration from some lower social standpoint.

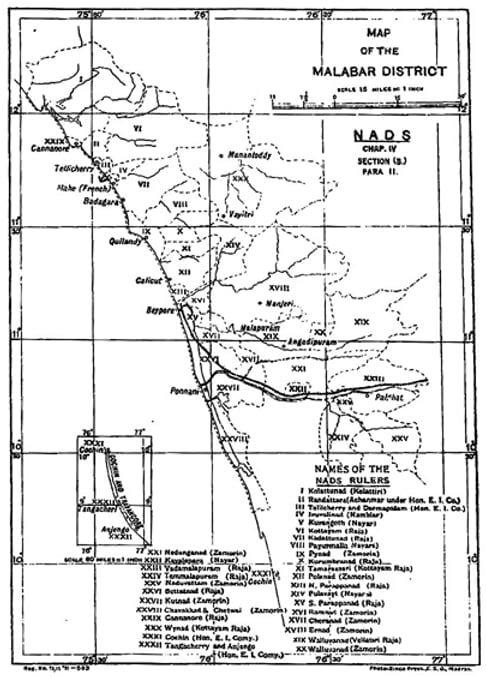

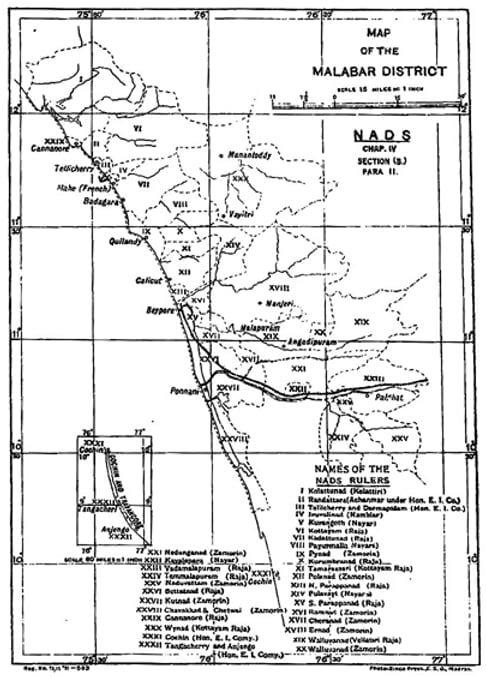

There’s also a sense that thesis scholars are unaware that the India of today did not exist then, nor did the Kerala of today. In South and North Malabar, there were some 29 tiny kingdoms or similar regions. The English administration amalgamated these into a single district under the Madras Presidency and later introduced a democratic system of governance there.

When such a profoundly transformative historical event occurred, various communities experienced upheavals, rewritings of social structures, and more. Many traditional elite groups were thrown into great turmoil.

This turmoil was not about the English entering their homes or seizing their wealth or women. Rather, it was the fear that communities traditionally below them would rise socially, take over their social positions and properties, and displace them from their esteemed verbal status.

It must be understood that, while it is true many lower-class individuals converted to Islam, there were also Islamic families in Malabar at that time who lived with traditional social prestige.

An accusation was made by Mr. Strange, a judge appointed by the English administration to study the Mappila conflicts, that H.V. Conolly, the English Malabar District Collector, was sympathetic towards Mappilas in general and lower-class Mappilas in particular.

However, the fact that H.V. Conolly was hacked to death by a few rogue individuals is portrayed by thesis writers as a grand, celebratory event tied to Islamic activism. It seems unlikely that individuals with even a basic understanding of fundamental Islam would attempt to conflate such foolish acts with Islam.

It is unclear whether the English Company officials’ observation—that elite Islamic individuals in South Asia possessed an unparalleled personal charisma—is reflected in thesis writings. It seems unlikely.

The historical accounts in these theses often appear to take the approach of relentlessly condemning the English administration.

This was not the reality. It seems likely that the influence of reading modern Indian academic history and watching fabricated historical films produced in Travancore or Bombay has impacted the mental framework of those writing these theses.

It feels like much of what is written above has already been mentioned earlier in this piece. Additionally, I recall noting the painful mental state of lower-class Mappilas, who had no direct pathway in society to communicate with senior English or British officials in the English administrative system.

In Malabar District, there was an English or British District Collector. Below him was a Deputy Collector, and below that, numerous Tahsildars. Both of these latter positions were held by local individuals.

It took the English Company decades to appoint officials (even Thiyyas from Tellicherry) with strong English language proficiency and other personal qualities to these positions through a public examination.

Until the Madras Presidency Public Service Commission began appointing senior officials, governance across Malabar was conducted by local traditional ruling families.

The Malabar Manual records that these individuals were outright thieves, backstabbers, corrupt, and utterly unscrupulous.

Amidst them, the English administration established legal codes and courts to enforce them. It seems that the judges in these courts were either English or other British individuals.

Land ownership remained in the hands of landlords, as it was then and still is in England. Thus, no issues were perceived there.

However, in Ireland, within Britain itself, such a social environment was indeed problematic. There, landlords leased agricultural land, but it was common for them to seize it back from tenants. These landlords were even labelled as land grabbers. The Irish blamed England for this predicament then, and that blame persists today.

Yet, the social flaw lay elsewhere. It must be understood that the presence of landlords was not the issue.

This piece has been written as a sort of warming up to resume writing. In the next piece, I will discuss a specific social barrier faced not only by lower-class Mappilas but also by other lower-class individuals and others.

4. Hindus and Muslims then

From around the 1830s, there seems to have been a persistent state of confrontation in South Malabar between certain groups of Mappilas and some members of the Brahmin faction.

Before delving deeper into this matter, it is necessary to clearly define the communities involved on both sides. Otherwise, the terms “Hindu” and “Muslim” might get conflated with the individuals defined by these terms today.

The so-called Hindus were the Brahmins.

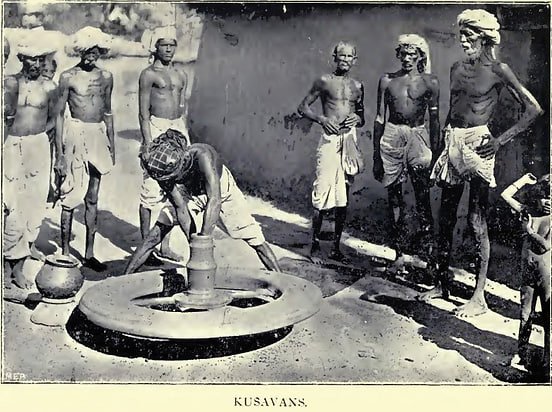

On their side at the time were temple priests and Nairs. Below them were the Makkathayam Thiyyas of South Malabar, and beneath them, numerous lower-class individuals who were merely dependents of the Brahmin (Hindu) faction. Groups like the Cherumas were, in reality, fully enslaved and semi-human in status at that time.

It must be clearly understood that today, a significant percentage of those in Malabar who display a Hindu identity are the Marumakkathayam Thiyyas of North Malabar and the Makkathayam Thiyyas of South Malabar. However, it was not with these two groups that Mappilas were clashing in the 1830s.

Generally speaking, Brahmins may have been vegetarians and refrained from using weapons. However, they were indeed the ones who socially suppressed other communities from the top of the local feudal language hierarchy. Their foot soldiers were the Nair overlords.

In an era when lower classes infiltrated Brahmin Hinduism, the Hindu religion began to reflect the characteristics of these new Hindus.

Now, regarding the Mappilas of that time.

In both North and South Malabar, Islamic followers had existed for several centuries prior. Among them, one section belonged to elite families. Many Islamic families, firmly rooted in Arab lineage, existed as highly distinguished individuals.

Moreover, during the Mysorean invasions, many Brahmin, temple priest, and Nair families converted to Islam. Several of them continued to maintain their elite status.

Above them, it seems there were also Islamic families in the Cannanore region with pure Yavana lineage, who likely preserved their bloodline with great purity.

In reality, none of these groups viewed the Brahmin faction in South Malabar with significant resentment. Furthermore, it appears that the Thangal families of Kundotti and their supporters also stood apart.

The Brahmin faction’s realization that Islam in South Malabar had a fearsome aspect came only when lower-caste communities began converting to Islam en masse.

The Hindu faction, both then and now, generally portrays this fearsome aspect as a natural psychological principle inherent to Islam and to Muhammad, who is understood as its spiritual leader.

However, the personal and social resentment among these lower-class Mappilas may merely be a reflection of their social condition.

This is because, until this social confrontation began, Brahmin factions, elite Islamic families, Arab trading groups, and others had lived together in harmony. Their common goal was likely to prevent lower-class individuals from rising above their socially constrained conditions.

Individuals have little chance of gaining knowledge beyond what they see and hear in society from birth.

In South Malabar, there were Brahmin landlord families. Their overseers were Nairs. Landlords leased land to Nairs and occasionally to Makkathayam Thiyya individuals. These tenants would purchase or lease enslaved individuals to work their farmlands.

These enslaved individuals had no revolutionary spirit. What they possessed was loyalty to their masters.

During the English administration, many lower-class individuals converted to Islam. They began leasing land. Many started engaging in trade, becoming owners of bullock carts and cargo boats.

These individuals experienced significant personal and psychological advancement.

This posed the greatest problem for Nair overlords. The local language codes could not accommodate such a transformation. It would be akin to an autorickshaw driver in Thiruvananthapuram addressing a police constable as nee, creating a linguistic coding issue.

Nairs desired to continue viewing lower-class Mappila individuals as their enslaved subjects. Traditionally, Nairs controlled their slaves by hacking and subduing them. Such actions fostered immense respect for them among the enslaved. This is similar to the attitude people today have toward the police.

If these Nairs became officials in the English administration, even the sole District Collector could not effectively control them. This is because everyone in the administration was local, and their psychological, social attitudes, thoughts, and conspiracies would spread like wildfire within the administrative machinery.

Neither side can be fully blamed. Both had their own anxieties. The local feudal language, invisibly orchestrating beautiful songs and festive celebrations, fuels these anxieties.

This language constantly reminds elite individuals that social leadership is an essential personality trait, silently urging them to fight to maintain their social eminence.

Blaming everything on the English administration, which plans social transformation from a distant, elevated position, is a highly practical approach. This is because there were likely no individuals in society capable or interested in explaining the English faction’s perspective to the people.

It seems most of what is written above has already been mentioned earlier in this piece.

It appears that Indian formal historians and thesis writers, without giving due consideration to many of these aspects, describe the attacks carried out by Mappila individuals in the 1830s as a freedom struggle against the English administration, thereby misleading readers and students of history.

5. If one could point out a common enemy

It is often said that Islam views kafirs as enemies. In ancient times, there may have been a general understanding among people that enemies should be killed. If the Quran records an opposition to kafirs, I am unaware of the context or circumstances in which this was stated.

It appears that such notions were quite prevalent in various societies in the past.

For example, English Company officials in Malabar received information that, according to the Sastra, it was a king’s duty to attack and plunder foreign lands.

The Sastra says the peculiar duty of a king is conquest.

— Malabar Manual

This statement could be cited as evidence that a form of “science” existed in this land long before the English Company began teaching it here.

I recall reading that the Old Testament of the Bible contains various aggressive intentions. The essence of this sacred text, which also applies to Muslims, may reinforce the idea that Islam has an aggressive nature.

However, among Christians, there is a term similar to “kafir” called “heretic.” In European countries (likely including Spain), heretics were brutally killed. This practice contradicts the Christian concept of human love.

In the Brahmin religion’s Bhagavad Gita, it seems that, amidst a battlefield, Arjuna is advised at length on the moral basis for using his martial strength to kill his relatives and teachers on the enemy side.

If this advice is taken out of the battlefield context, it might be understood as guidance on how individuals should act in life within this feudal language region. As I have not read the Bhagavad Gita, I cannot say more definitively.

The decision to apply such teachings in one’s life or society may depend on the type of people who receive them.

Many have used various methods to rally individuals as their followers.

One such method is the ideology of communism. The concept of bringing everyone to the same social level is indeed a spiritually uplifting idea. There is even an argument that those who believe in this spirituality need no other.

This spiritual thought is appealing on one hand, but reality lies elsewhere. These believers cannot even eliminate the rigid hierarchy in their verbal interactions, let alone eradicate social hierarchies and inequalities in society.

Many have tried to rally people for their conquests. The Maratha leader Shivaji successfully used Hindu ideals for this purpose. However, no one has ever said that Shivaji attempted to liberate the enslaved people of his land.

It seems that Mughal emperors and other Islamic kings or leaders in South Asia did not, beyond a certain extent, use Islamic religious fervour for their conquests. This is likely because most of the people they needed to rally were not Muslims.

However, Islam may be the most effective spiritual movement for rallying people. From the day an individual is born, they grow up adhering to various disciplines, almost like in a military framework. If a leader can rally such individuals under their leadership, they become a formidable leader. If the language is feudal, that person becomes akin to a military commander.

Nevertheless, people often unite only when a common enemy is pointed out.

The reason for discussing this is the notion that Mappilas in South Malabar may have considered killing kafirs a divine duty. Before this social attitude developed in South Malabar, it does not appear that elite Islamic families living in Malabar harboured such a notion of eliminating kafirs.

At the same time, the Brahmin faction viewed lower-class Muslim individuals with a degree of disdain.

This disdainful view was also directed by the Brahmin faction toward other lower-class communities in their region, which is a fact. However, the fact that lower-class Muslims did not submit as followers likely posed a significant problem.

There is another point to mention here, as noted in the Malabar Manual:

It may be safely concluded that, after the retirement of the Chinese, the power and influence of the Muhammadans were on the increase, and indeed there exists a tradition that in 1489 or 1490 a rich Muhammadan came to Malabar, ingratiated himself with the Zamorin, and obtained leave to build additional Muhammadan mosques. The country would no doubt have soon been converted to Islam either by force or by conviction, but the nations of Europe were in the meantime busy endeavouring to find a direct road to the pepper country of the East.

6. Explosive social mechanisms in society

In a certain region, there are a number of small-scale workers. They perform household tasks in the homes of many wealthy individuals, earning meager wages. The homeowners view them as filth, not allowing them to sit on chairs and requiring them to eat on the floor.

The homeowners give these workers their old, worn-out clothes, which the workers, their wives, and children wear. These workers hold great admiration and devotion toward their employers.

One of these workers gets a job in a new household, where they receive a good wage. The homeowners in this household treat them with greater respect, providing a chair to sit on and new clothes. They also create opportunities for the worker’s children to advance socially. However, it remains clear that this person is merely a servant in that household.

With each passing year, this worker, their children, and their family move toward higher social strata.

Does this development bring great joy to the other workers in their community?

Would they say, “Look, one of us is rising socially!” and rejoice?

Wouldn’t the families of other wealthy individuals in the region also become alarmed?

In reality, an explosive change occurs within the small community of these workers. The issue is not that the worker, their wife, and children begin using better clothes and amenities. The real problem is that this worker starts gaining greater verbal freedom socially. Physically, they sit closer to the elevated status of their employers at the workplace.

When the families of other workers refer to or address this worker and their family, subtle and significant changes in verbal codes begin to emerge unconsciously.

When this worker, their wife, and children refer to other workers and their relatives, a form of verbal degradation becomes inevitable. Remember, the language is feudal.

As the next generation grows, this worker’s children move into better jobs. They might even start businesses or industries. They may form marital alliances with elite families.

A rift and tearing apart unknowingly emerge within the workers’ community. Other workers and their families feel mentally shattered. They experience alienation and degradation in verbal codes from this worker’s family.

Many who attempt social engineering in feudal language regions without substantial knowledge, discernment, or wisdom often bring about such harmful consequences.

It seems that many of the caste-based reservations in place today stem from such initiatives.

The purpose of discussing this here is to point to a consequence of the social changes brought about by Islam in South Malabar.

By uplifting a small percentage of people who were socially defined and chained as lower-class, Islam did not bring joy to those around them. Instead, it caused alarm.

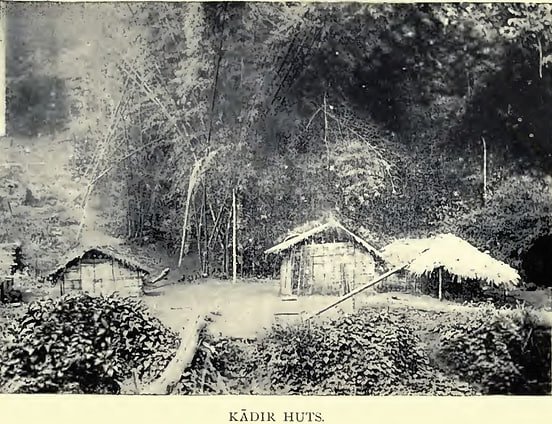

Groups like the Cherumas and similar communities were chained like cattle on landlords’ farmlands throughout their lives. Their understanding of the world was confined to the fields they worked in. They lived without any sanitation facilities.

Many among them converted to Islam. Ordinarily, this would not have been possible, as social norms would not permit it. Nairs would view such lower-class individuals breaking free as akin to a buffalo escaping its tether today—chasing them down and slaughtering them.

However, the administration changed. Clear laws were established. Courts were set up. A police system was introduced. Nairs lost their traditional authority. Although the District Collector was a solitary British citizen of the English Company, the legal system operated along a clear path.

If the English administration were to arrive in Malabar today and establish new legal systems, it would be akin to saying that today’s police could no longer arrest, beat, or kick people.

As Islamic mosques and madrasas were established in small locales, the community’s communication began to fill with rifts and explosive elements.

For the lower classes who lived with loyalty and affection toward landlords, the Makkathayam Thiyya community who viewed them with disdain, the Nairs who had enforced law and order in the region for generations, the temple priests working in Brahmin temples, and the Brahmin landlord families existing on various tiers, the question of how to handle this new Islamic persona within linguistic codes became perplexing.

These new groups were not the elite Islamic families.

With each passing generation, these Islamic groups began exhibiting significant social, economic, and lineage-based improvements in quality. Moreover, the daily call to prayer from their mosques and the Friday congregational prayers became a persistent nightmare for others.

It’s akin to a scenario in the Indian army where some sepoys band together and live in barracks without showing significant subservience to their officers. Previously, officers could keep each sepoy separate, transfer, or restrain them. Imagine the situation when that authority is lost.

If addressed as nee, they respond with nee in return. These defiant individuals also hold guns and other weapons. Furthermore, they have significant political and social connections. What can be done?

7. Insights from contradictory pieces of information

In South Malabar, many lower-class individuals converted to Islam and progressed significantly, both socially and personally.

The political environment enabling this transformation was provided by the English administration in Malabar. However, it does not seem that the hallmark of the English administration—namely, the English language and the social equality it could introduce through communication—spread widely in South Malabar.

There is mention of a Sayyid Abdulla Koya Thangal, reportedly a follower and successor of Sayyid Fazal Thangal. It is said that he urged social upliftment with the support of the English administration.

This information holds particular significance.

It supports a record in the Malabar Manual stating that Henry Conolly, the Malabar District Collector, believed Sayyid Fazal Thangal harbored no personal animosity toward the English administration.

Similarly, there is mention of a Sayyid Sanah-uUa-Makti Thangal from Veliyankode, who reportedly exposed flaws and superstitions in Christianity.

However, there is also a statement: He criticised the then prevailing reluctance to learn Malayalam and English.

It is unclear what is meant by the Mappilas’ reluctance to learn Malayalam. At the same time, Malayalam and English are, in reality, languages with entirely opposite characteristics.

This Thangal reportedly referred to English as a “hellish language,” stating that learning it would be useful when people reached hell.

It is uncertain whether this response reflects his opinion of people or something else.

When viewed in the light of social equality, it is Malayalam that is the true “hellish language.”

This Thangal was knowledgeable in English and even worked for some time as an Excise Inspector under the English administration.

It is noted that he gave speeches urging Mappilas to support the English administration and live in accordance with its laws, even citing Quranic verses for this purpose.

He also emphasized the need to address the educational backwardness of the Mappila community.

From these contradictory pieces of information, it can be inferred that elite Islamic figures, with advanced social and English knowledge, likely had to say many things to make the lower-class Mappilas understand their circumstances.

While lower-class Mappilas were formally Muslims, their agitation and violence in daily life were directed toward local social realities. Islam could not erase these social realities.

Social realities are shaped by the design of the local language. It does not seem that local Islam had the capacity to dismantle these realities, as the Mappilas were themselves ensnared by the local feudal language.

Moreover, formal education could elevate some individuals to high positions but could not alter or eliminate the explosive elements embedded in societal communication.

The ability to undertake such social reconstruction and cleanse societal communication lies with the English language. However, the environment in South Malabar lacked open support for the English language within Islam.

Why Islam could not support the English language is worth considering. I lack the information to provide a detailed answer to this.

However, a thought that comes to mind is that the method used to propagate Islam in South Malabar, and among other backward communities, may have relied on its miraculous stories.

Not all miraculous stories are necessarily foolish, ignorant, or superstitious; some may be true.

It’s akin to talking about mobile phones. Forty years ago, discussing such technology would have made listeners laugh, as they were educated in scientific knowledge and would not accept ideas contrary to human reason.

Similarly, the idea of the angel Gabriel appearing before Muhammad might seem impossible. Learned scholars of physics would know that individuals or entities cannot appear from a distance in this manner.

However, with today’s software technology, such as holographic projection, this could be achieved quite easily.

While this may be true, Islam in South Malabar had to nurture, educate, and sustain the lower classes there. No one had previously attempted to uplift and liberate them in this way.

Islam pursued this through spirituality, while the English administration did so without spirituality.

However, those who had to participate in Islam’s efforts were the local community members themselves. They needed to convey ideas that the lower classes could quickly understand and that would inspire great respect and admiration. Explaining complex intellectual ideas would likely have been challenging.

Moreover, there were elite individuals within local Islam. They, too, would not have favored teaching English to those who revered them, as it might erode their subservience.

Local landlords were not necessarily bad individuals. They, too, were fighting invisible forces to maintain their position in the feudal language region. They showed subservience to those they respected and either harshness or sweetened harshness to those they deemed inferior.

When Mappilas confronted them, they complained to the English administration, which was obligated to maintain peace in the region.

Not only the Mappilas but many lower-class individuals had grievances to convey to English officials. However, no direct channel for this existed. Moreover, they may not have clearly understood the root causes of their issues.

Similarly, the English administration was not entirely clear about what was happening in the region.

In England, too, there are landlords, and many engage in agriculture. However, there is no stifling social atmosphere for those at the bottom, unlike here.

8. The English Company and its direct administration

There is a tendency among some thesis writers and formal historians to use terms like "colonial administration" or "British colonial rule" when referring to the English administration in South Asia, unnecessarily misleading readers.

(It should be noted that in some old texts, certain communities, including Brahmins who migrated to Malabar, are also described as colonialists. This fact is often overlooked in the modern state of Kerala.)

These terms have also been used to create confusion about the reasons why some lower-class Mappilas in South Malabar acted violently in the 1800s.

Another related issue exists.

A question may arise: why couldn’t the English administration maintain the high social standards of continental Europe or England in British India?

There is a clear answer to this.

First, it must be noted that many who raise such foolish questions are college professors earning monthly salaries ranging from one to three lakh rupees for 13 months a year. Despite their income, a vast majority of India’s population still earns less than 4,000 rupees per month.

Thus, it can be said that the standard of living in India today remains far below that of England.

Yet, these scholars teach that this is because the English plundered wealth from here in the past.

In reality, the standard of living of the general populace in continental European countries like France, Germany, Italy, and Spain was likely far below that of England’s general populace. This disparity cannot be understood by measuring GDP.

The standard of a populace is embedded in their language. The standard offered by the English language differs from that of feudal languages and cannot be compared in any way.

Reading Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf revealed that the social standard of the general populace in Germany during Hitler’s time was similar to that of India’s general populace today.

Judging the personality of India’s common people by observing its soldiers is as foolish as judging the common populace of colonial European countries by their maritime traders.

Furthermore, the reality is not that the English came and conquered a country called India.

Instead, they amalgamated around 2,000 minor regions into British India, with the cooperation of local people and, to some extent, local royal families.

However, this act alone could not elevate the social standard of this country to that of England.

The social standard of England’s populace was not created or designed by its ruling royal family. Rather, it aligns with the codes inherent in the language of that land.

From this perspective, the mere presence of English rulers at the top of British India’s administration could not spontaneously alter the linguistic codes, behaviors, relationships, or animosities among the local populace. This is the precise reality.

All the social issues that existed here for ages continued to persist.

The claim by formal scholars that the English administration was a colonial, oppressive rule is incorrect. The reality is that the English populace lacked such an oppressive disposition.

Even today in Kerala, police and other government officials treat people harshly and violently. Blaming the Kerala Chief Minister for this behavior is as absurd as blaming the English colonial administration for the harsh conduct of local officials during their rule.

Another point to mention: when Tipu Sultan was defeated in war, the authority of Malabar fell into the hands of the English Company. However, in each region of Malabar, local kings, rulers, and chieftains continued to govern. It seems they cooperated with Tipu’s officials.

The English Company did not remove these local rulers. Instead, they were required to pay a portion of their revenue to the Company, which managed law and governance.

When this social change occurred, local rulers turned into outright plunderers. They began amassing wealth without any sense of responsibility, as opportunities for fighting and waging wars were eliminated.

QUOTE

“They (the Rajas) have (stimulated perhaps in some degree by the uncertainty as to their future situations) acted in their avidity to amass wealth, more as the scourges and plunderers than as the protectors of their respective little states.”

It was in this context that the English administration began paying pensions to local rulers and took over direct governance.

With this, for the first time in Malabar’s known history, the concept of a welfare state began to emerge.

Last edited by VED on Sun Jun 15, 2025 12:26 pm, edited 1 time in total.

9. Indication of an intolerable tyrannical rule

From approximately 1836 to 1854, I have gathered from the Malabar Manual that around 29 Mappila attacks occurred in Malabar, primarily in South Malabar. Some incidents also took place after 1854.

It does not appear that any of the 29 attacks I have listed were directed against the English administration. I am unsure if this is entirely accurate, but it seems no record in the Malabar Manual mentions a direct attack on the English side.

The reality is that the English administration was compelled to legally confront the perpetrators of these attacks and maintain law and order in those regions. Consequently, the English administration’s police, and occasionally its military units, had to directly deal with the aggressors.

What surprised the English side during these confrontations was that the aggressors were, under no circumstances, willing to surrender.

I intend to describe some of these attacks in this piece, perhaps in one or two subsequent writings. At that time, I will also analyze the courage of the Mappila attackers.

A point I wish to briefly mention here, as noted earlier, is that some lower-class Mappilas attacked the Hindus of that time, namely the Brahmins, as well as their servants and loyalists, such as temple priests and Nairs. Occasionally, some enslaved individuals who maintained affection and loyalty toward them also became victims of these attacks.

Of the 82 Hindu victims, the caste status of 78 is determinable. Of these, 63 were members of high castes (23 Nambudiri Brahmins, six non-Malayali Brahmins, and 34 others, very largely Nairs) and the other 15 of castes ranking below Nairs in the hierarchy, eleven being Cherumars, traditionally field slaves in Malayali society.

The point is that the lower-class Mappilas targeted the Hindus of that time. It should be inferred that they had no clear enmity toward those who are today known as Hindus, take great pride in Hindu traditions, and became Hindus after 1900.

Some Cherumars and Thiyyas who were attacked likely suffered because they were aligned with their landlords. There is another point to mention, which I will address later.

I recall CPS mentioning that, during their time studying in Tellicherry, they neither observed nor heard of any clear hostility toward Mappilas within their family or the surrounding Tellicherry community.

However, the reality is that significant social changes were occurring under the Hindu identity in the Indian nation.

When I was living in Alleppey, Travancore, in 1970, a major communal riot broke out in Tellicherry. It seems this event even led to Tellicherry being mockingly referred to as “Talachchedi” (head-chopper).

It appears that the nature of communal riots may have changed during this riot. Hindus from lower classes who had adopted the Hindu identity might have targeted even elite Mappilas in this communal clash.

If this is true, the communal riot turned nearly 180 degrees. I am unsure if this is accurate, but it is plausible—meaning traditional lower-class individuals attacked elite Islamic families.

(I have some points to discuss related to this, but I lack the scope to delve into them now.)

It seems that in some parts of Malabar today, communal attitudes have taken this altered form: lower-class Hindu groups attacking economically prosperous Islamic individuals. If this is happening, a clear explanation can be found in the local feudal language.

Regarding the riots in South Malabar, William Logan states:

The people have been driven to desperation and forced to take the law into their own hands by some intolerable tyranny.

The English officials, despite much deliberation, could not identify what this tyrannical rule was.

If someone had pointed out that it was the feudal language of the region, it is unlikely anyone would have believed it. After all, isn’t Malayalam often described as the mother tongue, maternal love, and motherhood itself?

Another point to highlight is that, in such communal conflicts, while both sides may cite their spiritual texts, quote passages, and reach a state of mental frenzy, the hostility is not primarily provoked by these spiritual sources.

Though both sides may claim that the Quran or other texts say this or that, the elements fueling communal hostility reside in the social language itself.

The clear cause of the communal attacks in South Malabar in the 1830s was the presence of lower-class individuals liberated through Islam. They gained significant mental freedom in a feudal language region. If they exhibited a mental personality akin to that of the English, it would indeed be problematic, as they were not English speakers. That’s the crux of it.

At the same time, they had no direct channel to interact with senior English administration officials.

In 1843, a violent incident occurred near Manjeri at Pandikkad. The perpetrators, who resisted the police, left behind an anonymous note (Warrola Chit). Addressed to the Valluvanad Tahsildar, a Shahid reportedly wrote:

“It is impossible for people to live quietly while the Atheekarees (adhigaris) and Jenmies... treat us in this way.”

That Shahid had no means to directly address English officials.

The English administration had no regard for local officials or landlords. However, they had no alternative but to rely on them to govern.

This situation persists in this country today. Officials treat people harshly and plunder the nation’s wealth. Yet, how can the country function without these officials?

In 1849, Syed Assan, Manjery Athan, and others who gathered at the Manjeri temple left a note stating that the behavior of landlords colluding with government officials was intolerable.

In England at that time, there were landlords and those working under them, but it does not seem that anyone harbored intense resentment or banded together to attack their landlords. If such incidents occurred, Malabar’s social conditions might have emerged there.

The lower-class Mappilas may have felt they were Muslims, but even that feeling came with various shortcomings.

10. Confrontations through degrading verbal codes

I am currently reading The Moplah Rebellion and Its Genesis, a research thesis written by Conrad Wood, a left-leaning social scientist from England, published in 1987.

While Wood appears to blame "British colonialism" when discussing the Mappila Rebellion, I have gleaned several insightful details from his study.

I have a habit of examining events in South Asia through the lens of feudal language codes. I have attempted to understand the developments mentioned in the above book in this manner.

In South Malabar, the English administration persistently tried to understand why some lower-class Mappilas resorted to social violence in certain areas.

It is unclear whether the aforementioned researcher grasped the significance of the local feudal language. Nor is it clear how much British officials in the English administration understood this. However, there are some indications.

To elaborate further on the advice given by Syed Fazl, the Mampuram Thangal, to lower-class Mappilas: he advised that if Mappilas addressed Nairs as ningal or ingal, Nairs should reciprocate by addressing them in the same manner.

It is uncertain whether words like ningal and ingal existed in South Malabar. I am using terms from North Malabar to explain this advice in this piece.

Note that ningal and ingal are words associated with different levels of social standing.

Syed Fazl Thangal likely gave this advice to enhance the social dignity of lower-class Mappilas. However, feudal languages are not suitable for such social engineering efforts.

It is unknown whether Syed Fazl Thangal used such elevated terms when addressing lower-class Mappilas. It seems unlikely that he did, suggesting a flaw in his advice.

Moreover, the lower-class Mappilas were not far removed from their harsh enslavement. They were distinct from elite Mappila families.

As Conolly noted:

The low Moplah, never over-courteous in his manner, is pleased at an order which brings (as he thinks) his superiors in rank and education to his own low level.

It can be inferred that lower-class Mappilas exceeded the boundaries of Syed Fazl Thangal’s advice.

Another of the Tangal’s orders, that every Moplah should use the polite form of the second person when conversing with Nairs only when the latter used the same, was similarly exceeded.

In other words, even if addressed as ningal, they might have responded with inji or ijj.

For enslaved groups like the Cherumars, under the English administration, no amount of labor under their landlords offered any path to personal, economic, or social advancement. They received meager wages.

In contrast, Mappila laborers often received better wages.

Using the social opportunities provided by the English administration, many of these individuals converted to Islam, shedding much of their social subservience.

Of course it was open to any Hindu wishing to mitigate the formidable array of sanctions he was subject to at the hands of the jenmi to do so by becoming a Muslim. In fact it was commonly observed by British administrators that considerable numbers of low-caste Hindus were exploiting this opportunity.

However, Nairs were often unwilling to acknowledge the dignity of these liberated lower-class individuals.

Even if a lower-caste person converted to Islam, Nairs would not hesitate to treat them with disdain and caste-based alienation. Consequently, verbal confrontations between lower-class Mappilas and Nairs arose in all social interactions.

It should be understood that children and women from Nambudiri, temple priest, and Nair families addressed lower-class individuals with degrading terms. Conversely, lower-class Mappilas began degrading the men, women, and children of these groups in their speech.

This does not indicate society moving toward a higher standard. Instead, it results in unrest and hostility spreading like a poisonous gas throughout society.

This is not to say that high-caste Hindus always readily accepted the relaxation of caste restrictions the conversion of, say, a Cheruman to Islam was supposed to entail, and collisions between low-caste converts and Nairs were sometimes the result.

However, William Logan noted in 1887:

As Logan stated in 1887, in the event of a Cheruman convert being ‘bullied or beaten the influence of the whole Muhammadan community comes to his aid’ and that ‘with fanaticism still rampant the most powerful of landlords dares not to disregard the possible consequences of making a martyr of his slave.’

At first glance, it may seem like a conflict between Hindus and Muslims. However, the issue is not Brahmin religious texts or Quranic verses. Rather, it is the mental unrest of various human communities trapped within the constraints of the local feudal language.

While lower-class Mappilas may have felt they were Muslims, in reality, they were not truly Muslims. I plan to discuss more related points in the next piece.

11. Within a 15-mile radius of Pandalur Hill

In South Malabar, the Mappila attacks on the Brahmin side were distinctly confined to two specific taluks: Ernad and Valluvanad.

To be more precise, these attacks occurred within a 15-mile radius of Pandalur Hill. Only one or two incidents took place outside this area.

“I have puzzled for twenty-five years why outbreaks occur within fifteen miles of Pandalur Hill and cannot profess to solve it,” - H. M. Winterbotham, Member, Madras Board of Revenue.

This was another fact that perplexed English administration officials.

These officials lacked access to various information. Today, one might collect data on a computer or search the internet, though even this can lead to inaccuracies.

Back then, English and other British officials were heavily influenced and limited by what they directly observed and what their subordinates reported.

For instance, English officials might encounter some continental Europeans in South Asia and converse with them. Due to their fair skin and English speech, they might initially seem similar. However, living in Europe would make it clear that continental Europeans were quite different from the English.

English Company officials held great respect for elite, fair-skinned Malabar Muslims of pure Arab descent, viewing them as honest, knowledgeable, and trustworthy.

However, understanding the South Malabar Mappilas, who exhibited contrasting social behaviors and personal traits, posed a challenge for these officials.

Both Company officials and subsequent British administrators were guided by a sense of obligation to govern impartially.

Another point needs to be addressed here.

By 1800, many lower-class individuals in South Malabar had converted to Islam and built mosques in their localities. They had various social leaders, including several Thangals. However, these Thangals often struggled to effectively control them.

Many of these Thangals had limited personal wealth or assets, relying on the voluntary contributions of their followers. They were likely known as Fakirs. Dependent on their followers’ donations for sustenance, issuing commands contrary to their followers’ desires or attempting to overly control them would have been difficult.

Instead of restraining violent lower-class Mappilas, these Thangals may have delivered speeches that incited them. However, there were instances where Thangals urged violent Mappilas to surrender, though these efforts were largely unsuccessful, with one exception, which I will discuss later.

In 1880, in Ernad, Mappilas clashed with a local landlord over building a mosque. When they consulted various Thangals, the response, based on their spiritual knowledge, was:

If the ruler orders the mosque to be relocated, that order must be obeyed.

Enraged by this advice, the gathered Mappilas publicly tore up the written directive in the streets.

It cannot be said that Mappilas in Ernad and Valluvanad had clear leadership. Each mosque and its surrounding community operated in near isolation, largely independent of external control.

However, the Makhdum Thangal of Ponnani was seen as the overarching spiritual leader. This Thangal’s direct authority was limited to a small group of Mappilas around Ponnani. There was no formal or recognized authority over other mosques or their operators elsewhere.

Unlike Christian churches, there was no clear organizational structure among Mappila mosques.

Meanwhile, the Kundotti Thangal was a different phenomenon. This Thangal belonged to a family from western Ernad. During Tipu Sultan’s brief control of Malabar, this family was exempted from land taxes, amounting to roughly 2,700 rupees annually.

When the English administration took over Malabar, this privilege was not revoked. Instead, the English Company provided various forms of support to this Thangal family.

It appears that throughout the English administration, this family consistently supported the English rule. What happened to this relationship in 1921 is unknown to me at this point. If I find relevant information, I will include it in a later piece.

Not only the Kundotti Thangal but also his followers demonstrated clear loyalty to the English administration.

Recall that the culprits who brutally murdered Malabar District Collector Henry Conolly were chased down and captured in Kundotti by the Kundotti Thangal’s men.

The Kundotti Thangal had a distinct group of followers, but they likely constituted only 20-25% of the total emerging Mappila population in South Malabar, roughly 30,000 people.

It is understood that most economically prosperous Mappilas were aligned with the Kundotti Thangal.

There is no historical record of any of the Kundotti Thangal’s followers being implicated as accused in the Mappila attack cases of the 1800s. Furthermore, when collective fines were imposed on certain areas as punishment for Mappila attacks, the Kundotti Thangal’s followers were exempted.

It seems that peace-loving Mappilas in Ernad tended to align with the Kundotti Thangal.

The Ponnani Thangal was believed to hold social leadership over the vast majority. However, his direct command authority was limited to a small group of Mappilas around Ponnani.

There was also evident enmity between the Kundotti Thangal’s faction and the Ponnani Thangal’s faction. The Ponnani faction reportedly attempted to label the Kundotti faction as Shia.

However, the Kundotti faction did not accept this characterization.

12. The backdrop of Hindu-Mappila communal tensions

The backdrop of today’s Hindu-Mappila communal tensions is as follows:

From those who were entirely enslaved under the old Hindu (Brahmin) order to both makkathayam (patrilineal) and marumakkathayam (matrilineal) Thiyyas, many began shifting away from their traditional social identities just before the 1800s.

A significant portion of these groups aligned with the Hindu identity, while another joined the Mappila identity. Today, it may be individuals from these two groups who express the most hostility and animosity toward each other in a communal context.

It seems likely that these two groups now represent the face of Hinduism and Islam in Malabar.

Both groups interact through local feudal language codes, navigating personal hierarchies that bind them to their respective communities. These feudal language codes lack pathways or mechanisms to accommodate individuals from one hierarchical group into another.

The English administration’s policy across South Asia was to classify everyone who was not Muslim, Buddhist, Jain, Sikh, or Parsi as Hindu. This was utterly foolish.

It appears that English officials often conflated Brahmin temple rituals and practices with the shamanistic traditions of other communities in their records. This misunderstanding likely contributed to the birth of modern Hinduism.

The attacks by lower-class Mappilas on the Hindu side in the 1800s are often misattributed by today’s Hindus, particularly those from former lower-class backgrounds, as seen in this flawed narrative.

The term “lower-class” itself refers to two distinct groups.

One group consists of tenants who leased agricultural land from Brahmin landlords for cultivation, including some Nairs and many Thiyyas. Among them, makkathayam Thiyyas were treated with slight social distance, while marumakkathayam Thiyyas faced no such distance.

These tenants were laborers, overseen by Nairs.

Below these laborers were enslaved communities tied to the agricultural land.

English Company officials noted that landlords and Nair overseers treated both laborers and slaves harshly. In the early days, local kings retained authority even under Company rule.

English officials frequently deliberated on how to address this harsh social condition but lacked any understanding of the invisible feudal language codes sustaining it.

Lower-class individuals expressed respect and deference, both verbally and through body language, toward landlords and Nair overseers who treated them harshly and abusively. For the English, it was difficult to comprehend why someone would show respect to an impolite individual.

Traces of this behavior are still visible in Malayalam today.

For example, when referring to a police officer who assaulted them, a person does not say, “He hit me,” but rather, “Addeham (he, respectfully) hit me.”

If addeham hits, isn’t that a good thing?

Indeed, during British rule, at least as late as the end of the outbreak period, should a jenmi have any important project in hand, his adian was expected to assist “with his money if need be, with his testimony true or false, and on occasions with his strong right arm.”

If a lower-class individual expressed an unfavorable opinion or word about a Hindu superior, it would lead to trouble.

The “smallest show of independence” was “resented as a personal affront.”

English administrative laws offered no protection for the lower classes, primarily because their officials were often local elites.

Moreover, the Hindu side could crush a lower-class individual within the bounds of the law.

A lower-class person labeled as troublesome could be declared a traitor to the land and community. This would make survival in the region impossible, barring them from spiritual gatherings, social spaces, village wells, riverbanks, and other public areas. Access to rural services would cease, and their household would lose social protection.

Such practices persist today. When police or government institutions target an individual, others align with these authorities, viewing it as loyalty to the land and patriotism.

Even the orders of local kings often required the consent of local landlords to be enforced. Additionally, many landlords operated private courts, dispensing their own justice and punishments.

In the early days, English administrative laws held little value in many areas.

Even so, there seems little doubt that this vassal relationship weakened under British rule which offered alternative means of protection to the adian ...

If the English administration were to return to Malabar today, establishing a legal and police system rooted in unadulterated English, the fear and subservience people feel toward the current police and officials would begin to fade. This is the essence of the matter.

Of course it was open to any Hindu wishing to mitigate the formidable array of sanctions he was subject to at the hands of the jenmi to do so by becoming a Muslim.

Over the decades, this evolved into enmity between lower-class individuals who converted to Islam and those who did not, shaping the face of local communal religious fanaticism.

Elite Muslim and traditional Brahmin families began to lose prominence.

The shadow of the local feudal language continues to operate in the background.

13. A mindset that persisted like a disease

With the end of Mysore rule, for some time, the English Company and local kings jointly governed both North and South Malabar as partners.

As mentioned earlier, the English Company officials faced a significant challenge in two taluks of South Malabar. During the Mysore rule, many landlords had fled to Travancore to save their lives. Upon their return, they found their lands occupied and cultivated by Mappila farmers, who treated the land as their own.