12. About the Namboodiris, Ambalavasis, and Nairs of Malabar

12. About the Namboodiris, Ambalavasis, and Nairs of Malabar

Written by VED from VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS

Previous page - Next page

Previous page - Next page

Vol 1 to Vol 3 have been translated into English by me directly.

From Vol 4 onward, the translation has been done by a translation software. So there can be slight errors in the text.

It was slightly difficult to make the translation software to understand that in Indian languages, there are hierarchy of words everywhere.

From Vol 4 onward, the translation has been done by a translation software. So there can be slight errors in the text.

It was slightly difficult to make the translation software to understand that in Indian languages, there are hierarchy of words everywhere.

Last edited by VED on Sat Aug 09, 2025 12:41 pm, edited 3 times in total.

Contents

1. About the filling up of the power of discipline and coordinated movement on some invisible realm

2. Swastika symbol, dual Aryans, rebirth, and celibacy in youth

3. Claims inside antiquity

4. The motives behind preserving vague ancient information as customs

5. Limitations in universally applying Vedic teachings

6. Another piece of advice exclusively for members of a particular community

7. The ubiquitous ‘respect’ in feudal languages within Vedic statements

8. On dharma, adharma, sins, and offences

9. When a sepoy ranker masquerades as an officer

10. The aura of personality beyond divine individuality

11. The all-pervasive framework entrenched in the feudal language nation

12. Strategies to chain down those standing outside the framework

13. On pledges brimming with hypocrisy and farce

14. Householder life and the five great sacrifices

15. Vanaprastha

16. Can driving out feudal languages eliminate the characteristics of the Kali Yuga?

17. The crude and the radiant in primitive customs

18. Brahmanical dominance and Sanskrit terminology

19. Anuloma and pratiloma relationships

20. First Parishas and Second Parishas

21. The burning desire to leap upwards and to hold someone below

22. Variations among the Ambalavasis

23. About the Ambalavasis in general

24. About the Moothathu or Mussathu

25. About the Pushpakan

26. The Chakyars

27. Those who infiltrated and inserted their own selfish interests and ideas

28. Chakyar Koothu

29. Chakyar Nambiar

30. Theeyattunnis and Nambissans

31. About Variers

32. Marars

33. About Kshatriyas

34. Malabar’s Kshatriya families and their connection to Travancore via Malayalam language

35. About Travancore’s royal families

36. The Kshatriya lineage of the Travancore royal family

37. Before discussing the Nairs

38. When the weak enter a brutal linguistic social environment

39. The origin of the Nairs

40. Overseers, enforcers of law, and warriors

41. The Nair preference for a lineage of noble descent

42. The possibility of a lower-caste lineage among some Nairs

43. The social and mental pathology propagated by feudal languages

44. Charna Nairs and Shudra Nairs

45. Nairs of foreign origin

46. Subgroups among the elite Nairs of North Malabar

47. Middle-tier Nair subgroups

48. Lower strata among Nairs

49. Yogi-Gurukkals and Wynadan Chettis

50. About the Nairs in Travancore

Last edited by VED on Mon Jun 09, 2025 12:49 am, edited 8 times in total.

1. About the filling up of the power of discipline and coordinated movement on some invisible realm

Image details: Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License

Image author: Rojypala

In connection with the jathakarmasamskara mentioned in the previous writing, consider the following sentences:

Quote 1: Later, in the child’s right ear, ‘Vedositi’ is softly whispered. ... Similarly, in the left ear, ‘Vedositi’ is chanted.

Quote 2: First, milk from the right breast and then from the left breast should be given to the child, it seems. End of Quotes

A thought suddenly came to mind. The question is this: If, instead of starting with the right, the left ear or left breast is used first, would there be any issue? Is there any significance in determining all this right and left? Are these not just a bunch of baseless, foolish behavioural rules, customs, and protocols?

If the left ear and left breast are used instead of the right, would it make any difference? Moreover, if at that moment one uses whichever ear or breast feels right, what’s the problem?

The answer to this is that in any disciplined movement, it is ideal to have clearly established conventions and step-by-step procedures.

In this context, think about the parade or marching in the military. Any marching that has evolved from the English military tradition begins with the left foot stepping forward. At the same time, the right hand swings forward. This gives immense strength to the coordinated and unified movement of that military group.

What is the use of marching or parades in the military? It’s worth pondering. Through such training, even a large group of soldiers instinctively moves in the same direction with the same steps, following specific orders. These include commands and movements like forward, about-turn, left, and right.

If, instead, when the command to march is given, each soldier moves whichever foot or hand they feel like, the total sum of the individual strengths of that military group would not be created. Instead, each person’s strength would neutralise another’s.

However, can we view the events happening in isolation within each Namboodiri family, without any physical connection to events in other Namboodiri families, as akin to a group of soldiers?

I’ll mention another related point a bit later.

The point here is to understand that behind the physical scenes we see, there is a transcendental software platform. On that platform, hundreds of isolated events can be brought together, coordinated, layered in various ways, and even arranged in ascending or descending order in an instant, and viewed as such.

A small example of this: if you search for “Temples Malabar” on Google Maps, a list of temples in Malabar appears. Yet, most of these temples are physically isolated, unconnected entities. Still, in the realm of the internet—something unimaginable to someone unaware of it—these temples are listed and appear interconnected in various ways.

Similarly, on transcendental platforms unknown to humans today, individuals and movements may be connected. One thing worth noting here is that for thousands of years, morning and evening rituals in Brahmin temples have been conducted without fail, possibly in sync with some inaudible, invisible rhythm of a drumbeat, timpani, or bugle call, following precisely orchestrated commands. When these are performed across hundreds or thousands of temples by Brahmins for centuries, morning and evening, it may be filling some invisible platform with the power of discipline and coordinated movement.

Now, let’s move to the sixth step in the shodasha kriyas.

Niskramana samskara

Quoting from the Wikipedia page:

Quote: The niskramana samskara is a ceremony where, on the third shukla paksha tithi after the child’s birth or in the fourth month on the child’s birth date, the infant is taken out of the house at sunrise in clear weather for nature observation. This ceremony is to be performed by the child’s father and mother together. After the Aditya darshan (sun observation), on that night (or another suitable day), chandra darshan (moon observation) should be conducted as per tradition. End of Quote

Shukla paksha refers to the waxing phase of the moon. Tithi is one of the lunar days, understood generally as a specific day.

Nature observation is indeed a significant matter. For a person growing up in a room surrounded by walls, there may be a slight lack in the input of information and other physical data into their brain’s software. This nature observation could be a remedy for that. More could be said on this, but I won’t delve into it now.

However, the significance of the specific tithis and shukla paksha mentioned in the niskramana samskara is unclear. There may be some connection to the internal codes of feudal languages.

While discussing these matters, I recall conducting such a practice myself, having absorbed some small part of this knowledge. However, I am neither a traditional Namboodiri nor did I perform these rituals by imitating the shodasha kriyas. I plan to elaborate on this later.

Now, let’s move to the seventh step in the shodasha kriyas.

Annaprashana samskara

Quoting from the Wikipedia page:

Quote: The annaprashana is the seventh ritual in the shodasha kriyas. (Sanskrit: अन्नप्राशन), also called choroonu.

This is when the infant begins eating rice-based food for the first time.

Until then, the child, who only consumed the mother’s breast milk, starts being given all types of food from that day.

This ritual can be performed in the sixth or eighth month. (The seventh month is apparently prohibited.) End of Quote

There’s nothing specific to say about this. However, remember that this too is part of the tradition of traditional Namboodiris. It seems others imitate it without knowing the full context. Yet, providing solid food for the first time appears to be a common practice among many communities.

The image provided above is of a choroonu. If this is celebrated as the annaprashana samskara, its purpose is unclear. The annaprashana samskara may be part of a cryptic plan to encode the social status of traditional Namboodiris and related intellectual codes into the infant’s transcendental software codes. The hidden purpose behind other communities performing the choroonu ritual is unknown.

Last edited by VED on Sun Jun 08, 2025 11:54 pm, edited 1 time in total.

2. Swastika symbol, dual Aryans, rebirth, and celibacy in youth

The next in the shodasha kriyas is the chudakarma samskara.

Quoting from Wikipedia:

Quote:

This ritual is performed when the child is three years old, or earlier, or after completing one year, during the uttarayana period in a shukla paksha at an auspicious moment, to shave the child’s hair.

The hair should be cut in the order of right, left, back, and front.

After cutting the hair, a paste of butter or milk should be applied to the head.

Then, after bathing the child, a swasti symbol should be drawn on the head with sandalwood paste.

End of Quote

Here, uttarayana refers to the period when the sun moves northward, i.e., from 21ᵗʰ March (winter solstice) to 21ᵗʰ June (summer solstice).

It is noteworthy that the procedures of the chudakarma samskara have a clearly defined first step and subsequent sequential actions. The act of cutting hair with mantra recitation across hundreds or thousands of Namboodiri children may involve some mysterious coordination and accumulation of power on transcendental platforms.

I have no clear information regarding the significance of the substances applied to the head.

However, let me say a couple of things about drawing the swasti symbol on the head.

The swastika symbol appears to have been used in many ancient spiritual traditions. It seems Buddhism and Jainism used it as well. It is also seen as the thunderbolt weapon of the Vedic deity Indra. It may have been used as a symbol of the Aryans, which could explain why it was adopted as the emblem of Hitler’s Nazi Party in Germany.

The concern here is that Indian textbooks claim the Aryans are from the Hindi-speaking regions of India. However, the German Nazis did not believe that the Aryans in India were the true Aryans. Whether they actively opposed this claim is unclear, but they were aware of their own Aryan lineage from long ago.

It seems that both the elite communities of South Asia and the Germans in continental Europe saw great significance in the swastika symbol. However, it appears that the English people did not claim any external heritage, likely because they did not need such crutches to enhance their personal stature. Their natural charisma was sufficient, and simply being English or from England was enough in those times.

If I may digress briefly, during the colonial period, German travellers in Africa reportedly carried a Union Jack (the British flag) in secret. They would display it in difficult situations to create the misconception that they were English, which often provided them physical safety.

Returning to the topic, I lack the information to definitively say whether symbols or seals carry spiritual or transcendental abilities or connections. However, digital technology today has proven that such things can encode various capabilities. Barcodes and QR codes, used widely today, are evidence of this. The NETC FASTag system recently implemented at toll booths is another example. It’s akin to inscribing a swasti symbol on the vehicle’s forehead, except it’s a FASTag.

Similarly, the clear utility of placing authority symbols on government vehicles is something I, having travelled in such vehicles in the past, have understood. The same applies to symbols like “Doctor,” “Advocate,” or “Press” displayed on vehicles.

When these symbols are used by India’s new Brahmins—government officials, doctors, lawyers, and journalists claiming Brahmin status—the lower castes, or ordinary people, are not permitted to use such swasti-like symbols.

The next in the shodasha kriyas is the upanayana samskara, noted as the tenth ritual. This raises the question of what the ninth ritual is.

This ritual holds a high status. It is said that through this ceremony, a Namboodiri child is reborn. This is the precursor to wearing the sacred thread. The ritual must be performed before the child develops vishayavasana, though I am unaware of what vishayavasana means.

This ceremony is conducted when the child is five years old and lasts four days. Through it, the Namboodiri individual (child) becomes a brahmachari and is expected to observe celibacy. The upanayana ritual concludes with the dandacharuka, though I do not know what this entails.

Let’s examine what “rebirth” means here. In English, Brahmins are often referred to as “twice-born.” The essence is this:

The first birth of a Namboodiri is merely physical. After this, the individual must be born spiritually. With this second birth, they begin reading and studying Vedic literature, dharma shastra texts, and other sacred scriptures.

However, how much meaning lies in saying that the individual becomes a brahmachari and must observe celibacy for some time is unclear. It is written that men must observe celibacy until age 25 and women until age 20.

It seems that elder Namboodiris could marry girls as young as ten, twelve, or perhaps fifteen, though I am not certain of the exact age.

However, it seems unlikely that the celibacy required by the upanayana samskara can be enforced on boys. At the very least, men might engage in mushtimaythunam or hastamaythunam (masturbation). Maythunam is a Sanskrit word, hence considered refined. But in colloquial Malayalam, there are crude terms for it as well.

It should also be noted that the beauty of a naked woman, clothed or unclothed, was not a rare sight. The lines of Vayalar Ramavarma describe a Namboodiri maiden standing at the bathing ghat in an agraharam, with wet clothes clinging to her and hair dripping, tempting someone to pinch her.

It’s worth remembering that maythunam is one of the five makaras in Tantric practices. A thought just crossed my mind: would mushtimaythunam suffice as a substitute? Women may not always be available for such esoteric Tantric practices!

There’s a doubt: would engaging in mushtimaythunam cause a twice-born Namboodiri to lose their celibacy?

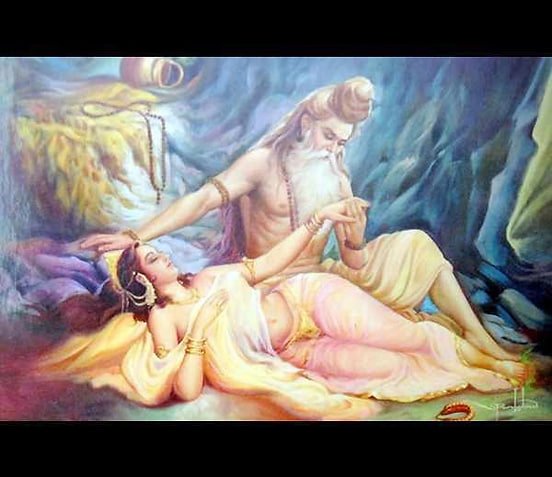

Image details: This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license

Image author: MennasDosbin

The image provided above shows four types of swastika symbols.

3. Claims inside antiquity

The next in the shodasha kriyas is the vedarambha.

Quoting from Wikipedia:

Quote:

The vedarambha samskara is conducted at home along with the upanayana, and the vidyarambha samskara is performed at the gurukula. End of Quote

It appears that once a Namboodiri child begins wearing the sacred thread, they start studying the Vedas and other sacred texts at home. It is not recorded who teaches these subjects. However, since the upanayana samskara is performed at age five, it can be understood that studies begin from that age.

It is noted that education takes place at a gurukula. This suggests there were schools exclusively for Namboodiri children. This raises questions about what was taught there and by whom. If it is claimed that a guru teaches, one might wonder what educational knowledge the guru possesses and where they acquired it.

These writings may imply that, in ancient Malabar, traditional Namboodiri families had significant educational institutions and gurukulas, but it seems there is little substance to this.

The reason is that traditional Namboodiri families were themselves isolated. Moreover, their travels outside the illam (household) were likely limited to small-scale formal obligations. Traditional Namboodiri women were not allowed to look at other men’s faces, required a palm-leaf umbrella, and needed a Shudra maidservant accompanying them.

Without these, the situation would be more problematic than an IPS officer today walking down a public road in a churidar and kurta, unrecognised by others. However, it’s worth noting that both groups would have arrangements nearby to handle troublemakers with force if needed.

Among traditional Namboodiri youth, those in the position of anujan (younger sibling) were not permitted to marry Namboodiri women. They had to seek Nair or Shudra households. It’s akin to saying that only the eldest son from an IAS/IPS family can marry into another IAS/IPS household, while younger siblings must somehow align with families of lower status, like peons.

Not only around their illam, but also along the paths they travelled, lower-caste people of various levels lived. Avoiding them in sight and thought would have been quite challenging.

It’s easy to wax eloquent about Hindu (Brahmin) heritage and tradition. However, without considering Malabar’s social realities and the rigid hierarchical nature of its language, such claims can only be convincing through rhetorical flourish. For example, consider vanaprastha and sanyasa, the stages just before the final antyesti in the shodasha kriyas.

Many descendants of communities once subjugated under traditional Namboodiri (Hindu) society, who now claim to be Hindus, say that in ancient times, their ancestors would go live in the forest at age fifty and later become sanyasis.

The flaw in this claim has already been pointed out. The shodasha kriyas are part of traditional Brahmin customs, not those of other communities. Moreover, these shodasha kriyas likely originate from the traditions of a people outside this subcontinent, dating back one or two thousand years, which poses another issue.

The problem with waxing eloquent about vanaprastha and sanyasa today is that, in recent centuries, it’s unlikely that traditional middle-aged Namboodiris in Malabar (or elsewhere) went to live in forests.

It is explicitly recorded in Malabar & Anjengo that Brahmins did not practice these two stages.

Quote from Malabar & Anjengo: …two of the stages in the Brahman’s life prescribed by the Vedas, namely, vanaprastha (or dwelling in the jungle) and sanyasa (or renunciation of all secular interests and occupations); a dispensation, which is somewhat superfluous in the present, whatever may have been its value in the past. End of Quote

The gist of the quote: The Vedas prescribe vanaprastha and sanyasa as two distinct stages in a Brahmin’s life. However, in these times, they are redundant and unnecessary directives. Their relevance in ancient times is a matter to be examined. End

This suggests that in the 1700s and 1800s, the relevance of vanaprastha and sanyasa was limited to mere claims.

It was noted earlier that studies begin at age five. Whether starting education before age five would cause any issues is unclear, as no such record is found.

Did girls attend such gurukulas?

Education can be said to involve learning things useful and applicable to life. It’s uncertain how true it is that Namboodiri children laboriously studied arithmetic, geometry, algebra, or other advanced mathematical branches, scratching on the ground or palm leaves. One might also question the purpose of studying these.

Even without knowledge of geometry, traditional carpenters in those times built grand structures using wood, stone, and lime. If they had studied such subjects in gurukulas, it might have benefited their craft. However, they were not granted access to these schools. Moreover, it’s unclear how many traditional Namboodiris in Malabar were proficient in these modern mathematical disciplines.

Assuming some mathematical texts were found as palm-leaf manuscripts from some part of the subcontinent during the English rule, claiming that Brahmins of this subcontinent were skilled in these matters seems somewhat foolish.

Readers should note that the shodasha kriyas have only a very tenuous connection to modern India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and their respective peoples, including Brahmins.

Over the past few centuries, by blending various regional languages to different degrees and infusing them with Sanskrit vocabulary, the rich languages and Sanskrit-based traditions we see today have spread across the subcontinent, along with Hindu religious beliefs, as I understand it.

This translation adheres to the provided rules, using British-English conventions, specific terminology (e.g., Namboodiri, shodasha kriyas), and requested substitutions. Let me know if you need further sections translated or additional clarification!

4. The motives behind preserving vague ancient information as customs

Image details: The painting (1859) is of unknown authorship. It is unclear what it represents. It could depict affection, devotion to the guru, gurukula education, blessings, or the atmosphere of a forest hermitage.

The next in the shodasha kriyas is the samavartana samskara.

Quoting from Wikipedia:

Quote:

The samavartana samskara is the ceremony where, after completing education, a student offers gurudakshina (a gift to the guru) and returns home with the guru’s blessings.

Men must observe celibacy until age 25, and women until age 20, as per the rule.

A student who has completed gurukula education is called a snataka.

At the time of samavartana, the symbols of celibacy, such as the valkala (bark cloth) and danda (staff), are discarded.

Thereafter, standing facing the sun, the student performs Aditya japam and cuts their nails and hair. End of Quote

The words “education” and “student” in the quoted text likely have little connection to the concepts of education and student as developed or inspired by the English administration in this subcontinent. However, they may have a strong connection to the modern Indian concepts of vidyabhyasam (education) and vidyarthi (student).

Similarly, there is likely no real connection between the teacher envisioned by the English administration and the guru mentioned above. Translators often mistakenly equate these terms, creating the impression that they are the same. The English side may not even realise the error in such translations.

Before a guru, a student stands in subservience, using deferential language and body gestures like rising or bowing. The guru embodies the attitude that “you are my subordinate, you must obey me, and you must display your subservience when you see me.” This attitude is expected to naturally fill the student’s mind.

The relationship between them is a guru-shishya bond, woven with words tied to hierarchy, like “you” (highest) and “nee” (lowest). In contrast, the English teacher-student relationship lacks such a feudal linguistic web, intricate social structure, or entanglement.

When it is said that children lived and studied at a gurukula from a young age, it must be understood that thousands of years ago, when the Vedas were composed, such facilities existed for the elite of that society. However, it’s unlikely these were idyllic forest hermitages, ashramas, or rishivadas as imagined today.

Moreover, since the Vedas were written thousands of years ago, it can be opined that various knowledge and technologies existed for study then. However, there is no evidence that Malabar’s Namboodiri community had access to such systems.

If children were sent to live at a guru’s house, they likely had to do kitchen chores, wash dishes, and launder clothes. It’s unlikely that separate servants were employed for these tasks.

However, in the northern parts of this subcontinent, large religious educational institutions likely had numerous slave-village communities under them. Yet, it seems unlikely that these institutions had any connection to Malabar’s Namboodiri families.

Not only children but even adults might have been used for sexual education and observation. Back then, girls were likely seen as meant for sexual and household purposes, not for pursuing a BA or MA to secure government jobs. Such ideas likely emerged in parts of Malabar only with the advent of English education.

Image details: A classroom scene (1936–1947). Likely from Travancore, around 1936–1947, it appears to be an attempt at gurukula-style education. Today, it could be called home tuition. The individuals in the photo are of unknown community affiliation.

It’s also known from various sources that boys were involved in sexual education. It’s almost certain, historically, that both boys and girls were taught practical aspects of sexual education. Parents likely had little concern about this, as the mother was just one of many women in a joint family household doing chores, and the father might have had children with multiple women.

The greatest concern for Namboodiri families was likely ensuring their children did not adopt the subservient traits of the lower-caste people living nearby. If the value of feudal language was lost, what was the point of living?

Families ensured their children were taught various knowledge by an elite person. If a low-status person taught a boy or girl, the child might become repugnant. This likely applied to practical sexual education as well.

When writing this, it’s unclear how gurukula education and smarta vichara (orthodox inquiry) could be reconciled. Smarta vichara likely arose because Namboodiris were entangled with lower-caste people. If there were no lower castes, smarta vichara would lose its relevance.

That students observed celibacy, offered gurudakshina to return home, were called snataka, discarded symbols of celibacy like valkala and danda, performed Aditya japam facing the sun, and cut their nails and hair—these may have been practices from a different social context thousands of years ago in another region.

There must be a clear hidden motive behind traditional Namboodiris in Malabar imitating and preserving these hazy, ancient details as customs. I plan to address this in the next writing.

Note: The valkala mentioned above is said to be tree bark or a cloth made from it. Does this mean Namboodiri boys and girls lived in gurukulas wearing bark cloth? Also, did they refrain from cutting their nails and hair? Perhaps it only means that upon leaving the gurukula, they had to trim their hair and nails as a rule. It’s worth noting that hair grows thickly not only on the head and face but elsewhere on the body.

The danda was a staff carried by brahmacharis in ancient times, typically a 75 cm palash wood stick. Sanyasis reportedly used a bamboo staff with seven nodes as their danda. End of Note

However, if it’s understood that none of this pertains to Malabar’s Namboodiris, there’s no real issue. Rather, it may be that they claim such things in their eagerness to glorify their traditional legacy.

Related to the samavartana samskara, the first part of the acharya’s advice in the Taittiriya Upanishad is said to be as follows:

“Speak the truth, practice dharma.

Do not be negligent in studying or teaching.

Do not err in maintaining health and skill.

Do not falter in increasing prosperity honourably.

Respect deities, parents, and gurus.

Never engage in sinful acts.

When giving, do so willingly with a pleasant expression.”

The word pramada mentioned above means:

Forgetfulness, failing to do what should be done

Ignorance

Mistakes due to carelessness

Wrong opinions

Inattentiveness

More about this acharya’s advice will be written in the next piece.

5. Limitations in universally applying Vedic teachings

Let’s examine the words from the Taittiriya Upanishad quoted in the previous writing.

These words relate to the social context of a different people from thousands of years ago. Moreover, they are a Malayalam translation of words written in another language.

The meanings, implications, and understanding of these words may have limitations and nuances that are difficult to grasp in Malayalam or in today’s social context. Nevertheless, recognising that Sanskrit was a deeply feudal language can be useful in analysing these words.

Consider:

Quote: Speak the truth End of Quote

Remember that Sanskrit is a feudal language. In English, the precept of “speaking the truth” is itself limited in various ways. In English societies, there is a human right to lie. In feudal language regions, however, the elite have the oppressive right to force the truth out of subordinates by beating them if they lie.

At the same time, in feudal languages, there is no fault in lying to subordinates or those deemed inferior. In fact, lying to them in various ways is often a necessary part of maintaining discipline and leadership.

Beyond this, the concept of “speaking the truth” may have deeper roots. In feudal languages, individuals are not standalone entities. For example, a young person in a family has a defined position and relational ties—father, mother, aunts, uncles, elders, their children, siblings—all embedded in a rigid hierarchical code of relationships.

Suppose this person becomes a sub-inspector in the police.

Now, they are a point in another intricate hierarchical web, comprising senior officers like circle inspectors, deputy superintendents, IPS officers, and lower-ranking constables, all within a grand structure of power, influence, and scope.

In both these hierarchical systems, this person has a clear duty, obligation, responsibility, and commitment to speak the truth and avoid lying.

However, sharing the truth of one system’s matters in another system may be a procedural violation. For instance, while the person may feel obligated to truthfully answer an uncle’s question within the family, police department rules may prohibit sharing such truths.

Here, we see that the simple advice to “speak the truth” is caught between conflicting duties, obligations, responsibilities, and commitments, swaying between sides, limited by whichever prevails. Thus, this Vedic teaching is not a universally applicable precept.

(Note: The above point also has a strong connection to marital life in feudal language regions. I plan to discuss this later. End)

Another point: in feudal languages, there is no need to speak the truth to the lower castes. In reality, Brahmins did not consider them fully human. It’s understood that Indian officials today still hold such attitudes.

Thus, the Taittiriya Upanishad’s teaching of “speak the truth” may lack significant relevance beyond a hollow precept. Its true depth likely lies in maintaining honesty with one’s own people, family, and community, whom Brahmins considered human.

Quote: Practice dharma End of Quote

This phrase faces a similar issue.

The dharma of a police constable includes saluting superior officers, standing up in their presence, obeying their orders, refraining from contradicting them, and using subservient language.

Conversely, failing to salute, not standing up, disobeying orders, expressing dissent, or behaving without subservience are not dharmic behaviours.

However, behaving rudely to a common labourer, using abusive language, making explicit sexual remarks about their mother or sisters, slapping their face, or kicking them on the ground would not be seen as adharmic (unrighteous) within the police system.

Yet, if this constable behaves this way toward superior officers, it would be considered grossly adharmic.

It’s said that Sanskrit dharma shastras reflect this flaw: dharma is about upholding social hierarchies, and acting against them is adharmic. The Sanskrit word dharma likely has little connection to the English word “justice” beyond a flawed translation.

A similar issue appears in Greek traditions. The Greek concept of justice (δικαιοσύνη) in ancient literature has only a tenuous link to the English concept of justice.

Reciting, listening to, interpreting, or delving into the depths of Sanskrit verses to extract pearl-like words, sounds, and hues can be fascinating. However, this does not lead a person, their personality, or their community to the simple elegance of an English social context.

6. Another piece of advice exclusively for members of a particular community

Let us now examine the other sentences in the quotation from the Taittiriya Upanishad.

Quote: There should be no negligence in studying or teaching. End of Quote

This is a good point to make. However, it must be understood that this advice is clearly intended only for members of a particular community. There is no explicit guidance in these words that their knowledge and technical expertise should be shared with other groups, or that individuals from other communities should be made their gurus, teachers, or mentors.

This is indeed a significant matter.

Sharing the knowledge and technical skills, painstakingly developed over centuries within their own tradition, with those considered lower, teaching them, training them, and thereby enabling the lower classes to grow in knowledge and expertise—and then making individuals from those classes their own gurus or mentors—is, in feudal language, sheer folly.

The reason is that by sharing such knowledge and expertise with those who could potentially compete with or suppress them, without any effort or centuries of hard work, and without valuing these matters, such groups would appropriate this knowledge, claim it as their own, and attempt to suppress or belittle those who shared it with them.

However, it is the pristine-English speakers who lack any such discernment or understanding.

In English colonial territories, the people of those regions, who have fully absorbed the vast knowledge and expertise provided by the English, now show a desire to somehow suppress the English.

The capitalists in English-speaking nations, who provided advanced technologies to magnates in socially inferior countries like China, have, in reality, committed outright betrayal and harm against their own people. This is because such individuals did not create or develop this vast technological knowledge with the support of their own traditions.

On the contrary, the great technological discoveries, built through centuries of slow, step-by-step efforts, experiments, and observations by the English, were handed over to foreign magnates by some individuals without any qualms—a sheer act of roguery. Standing on the platforms thus obtained, other communities are making various new inventions.

The Brahmins, however, never engaged in such foolishness in this regard. They never shared their spiritual or temporal knowledge and skills with those placed below them in feudal languages. It appears that they maintained this social boundary in Malabar from ancient times until the arrival of the English administration.

Al-Biruni (Circa: 4 September 973 – 9 December 1048), a Persian scholar, wrote about the elite communities of South Asia as follows:

They are by nature miserly in sharing their knowledge, and they take the greatest of efforts to hide it from men of another caste among their own people, and also, of course, from foreigners.

It seems that the Vedas and Upanishads pretend to ignore the hierarchical codes of the Sanskrit language. This is because their teachings, advice, and moral codes appear to be intended for those belonging to the higher word-codes in society. However, since I (this writer) do not know Sanskrit, I cannot authoritatively confirm this matter.

There is another aspect to sharing education and technical skills.

This is an even stranger matter than what was mentioned above.

In feudal languages, no one appreciates another person teaching a few students under their control without their permission or loyalty.

It is very clear that the other person could become a sir, master, leader, or someone who steals their followers, turning them into their own subordinates and followers, defining them with lower terms like "nee," "eda," "edi," "avan," or "aval." This is indeed a significant problem.

In feudal language regions, providing education does not mean distributing fundamental knowledge and skills generally. Instead, the clear intent of the person promising to provide knowledge, expertise, or skills is to assemble a group of people who express subservience to them through words, body language, and other means, bringing them under their control.

In feudal languages, the deliberate ulterior motive of sharing knowledge with another is to appropriate their followers. It appears that local English speakers still have no understanding of this matter.

Since this is a well-known fact, either explicitly or implicitly, in feudal language regions, even in the past, no family would approve of someone without loyalty, obligation, subservience, or respect teaching or training their children.

If a Brahmin were to organise and teach the children of socially lower groups like Ambalavasis, Shudras (Nairs), Muramakkathaya Tiyyas, Makkathaya Tiyyas, Malayas, Ezhavas, Mala Arayans, or others, it might not be appreciated by the social leaders of those lower communities. This is because such an event could likely lead to those children breaking away from their subservience and aligning under another leader.

Moreover, the children under their control would establish direct connections with a Brahmin, who is socially higher. This, too, is a significant issue. Socially, mentally, and personally, the warning that a development surpassing them is about to occur would enter these people’s minds. This would certainly cause significant problems in feudal language communication.

If things proceed this way, the notion that individuals greater than oneself could emerge within one’s own community would not be a daydream but a nightmare.

I (this writer) have experienced another issue related to this online multiple times. I have noticed that when I write something online, efforts are made to ensure others do not see it. There is much to say about this in detail, but that can be discussed later.

In brief, whenever I provide a link or reference online to one of my books, it has often provoked strong irritation in many people. One clear reason could be that those who have achieved great qualifications through formal education find things written that they never encountered in the paths they followed.

Another issue is that a small, seemingly trivial link leading to a vast repository of knowledge has provoked strong opposition in many, as experienced by following such a link.

Returning to the main topic.

To understand that the words in the Taittiriya Upanishad, Quote: There should be no negligence in studying or teaching. End of Quote, hold relevance beyond being advice for a small group speaking feudal languages, one must grasp many things not explicitly stated in those words.

The fact that there are life, minds, and people beyond the universal boundaries of those defined as elite in feudal language words is indeed a significant matter.

7. The ubiquitous ‘respect’ in feudal languages within Vedic statements

Let us now examine the other sentences in the quotation from the Taittiriya Upanishad.

Quote: There should be no negligence in maintaining health or in acquiring expertise.

There should be no error in increasing prosperity in the best manner. End of Quote

These two points may be general pieces of advice. But let us look at the next one:

Quote: Respect deities, parents, and teachers. End of Quote

In these words, the ubiquitous concept of ‘respect’ in feudal languages appears very clearly.

Respect, or rather subservience, is required towards deities.

It is understood that the Sanskrit and Vedic term deva does not mean ‘God’ as such. I (this writer) will not delve into that topic now. However, if one wishes, this sentence can be understood as a mindset requiring subservience towards God. It is understood that this concept does not exist in English. In English, praying to God is not done with the attitude of a subordinate. The reason for this may be that the concept of subservience, as such, does not exist in English.

The next point is that respect, or rather subservience, is required towards parents and teachers. At first glance, translating this requirement into English would show no difference. In English, too, there is no mindset that one should not have respect for parents and teachers; respect is expected.

However, the issue arises because the word ‘respect’ in feudal languages and the word ‘respect’ in English do not represent the same thing. In feudal languages, ‘respect’ is synonymous with ‘subservience’ and should be seen as such. In contrast, in English, there is no connection whatsoever between the word ‘respect’ and ‘servility’.

The connection between ‘respect’ and ‘subservience’ in feudal languages arises because words like nee (lowest you) and angoo (highest you) infiltrate such expressions. These words are entangled with numerous practices, such as standing up to show respect, bowing, adding honorifics after names, and so on.

In English, the word ‘respect’ is entirely different. Moreover, in English, it is acceptable for a ‘Father’ or ‘Mother’ to feel ‘respect’ towards their children without causing issues in word codes. Similarly, it is desirable for teachers to have ‘respect’ for their students. In other words, teachers should behave respectfully towards their students.

If such words are translated or interpreted into feudal languages, they would appear utterly foolish.

What nonsense is this? Should a teacher stand up when a student enters? Should they address the student with honorifics like ‘Sir’ or ‘Brother’?

However, to explain this differently in feudal languages: teachers should not behave disrespectfully towards students.

Even this is not something feudal languages can easily handle. This is because teachers are expected to address students as nee (lowest you), refer to them as avan (lowest he) or aval (lowest she), and give instructions affectionately with terms like eda or edi. So, how can respect be given to avan or aval?

English and feudal languages are indeed two entirely different worlds.

To clarify this further, let us consider the example of the military.

In the Indian military, the system is such that ordinary soldiers and their kin are addressed with terms like tu (lowest you), app (you), or just their name with saab or memsahib (highest he/she), and us or un (lowest he/she). On one side are the ordinary soldiers and their kin, and on the other are the officers and their kin.

In such a system, it is impossible to enforce a rule requiring ‘respect’ towards ordinary soldiers or prohibiting disrespectful behaviour towards them.

However, since English lacks such devilish practices, if there were a rule prohibiting disrespectful behaviour towards ordinary soldiers, it would operate at an entirely different standard.

Since this is a deeply complex topic, I (this writer) intend to delve into it later.

The words Quote: Respect deities, parents, and teachers. End of Quote seem to have no deeper, enchanting significance beyond reinforcing the devilish requirements of feudal languages.

There is no antidote, magic, or mystical essence in these words to elevate those who are considered lower.

Even if the lower classes learn to speak pristine English, these lines cannot provide the mental elevation they would gain. Being Sanskrit words, their sound may seem to carry the fragrance of a mantra. In reality, that mantra may only be attempting to suppress those who are lower. Nevertheless, the aesthetic beauty of these words might provide the lower classes with an intoxicating allure, akin to a narcotic.

Last edited by VED on Sun Jun 08, 2025 11:57 pm, edited 1 time in total.

8. On dharma, adharma, sins, and offences

Let us now examine the next sentence in the quotation from the Taittiriya Upanishad.

Quote: Never engage in sinful acts. End of Quote

Such writings may lead a person into a moral dilemma.

What constitutes a sin is a significant question in itself. It is understood that the English word for paapam (sin) is ‘sin’.

In Christianity, there is the concept of the Seven Deadly Sins, which are pride (arrogance), greed (avarice), lust, envy, gluttony, wrath, and sloth.

Similarly, acts considered sinful include homicide, abortion, infanticide, fratricide, patricide, and matricide.

There are other sins as well, such as homosexuality, slavery, neglect, bigotry, and exploitation.

However, equally or even more severe than these is the unpardonable sin of blasphemy against the Holy Ghost, or Yahweh, or God, or God’s name.

It seems that sins in Islam may be somewhat similar, though I (this writer) lack the precise knowledge to confirm this.

Many of the sins mentioned above appear to be, to some extent, personal failings or weaknesses.

Others were defined as legal offences when the English administration enacted laws in this subcontinent. Thus, they may not strictly fall under the definition of spiritual sins.

Some sins were suppressed through social reform efforts and legislation by the English administration.

Consequently, the sin that religions most strongly oppose may be blasphemy against God or God’s name. It appears that the English administration did not address such sins, though I am not certain.

The sins relevant here are those defined as such in the Brahmin religion. It seems these should be based solely on the Vedas. However, today, in the Brahmin religion, or Hinduism, there is a tendency to label anything mentioned in various texts—written across different centuries over thousands of years with little connection to each other—as Hindu doctrine.

In that sense, any doctrine can be proclaimed as Hindu doctrine. There is little significance in this.

In the Brahmin religion, two concepts are evident: dharma and aparadham (offence).

As mentioned earlier, dharma may not have a strong connection with the English word ‘justice’ (fairness or righteousness). In the feudal language of Sanskrit, which socially and familially organises communities in a hierarchical structure, dharma likely refers to behaving in accordance with that structure, establishing personal relationships accordingly, and maintaining discipline in line with it.

It is somewhat akin to members of the Indian police forces behaving in a way that does not disrupt the hierarchical tiers of their institution.

Acting contrary to this would be adharma.

The concept of aparadham is similar.

Entering temples in vehicles or wearing footwear, not participating in festivals, not bowing before the deity, eating before making offerings, speaking loudly, turning one’s back, self-praise, or slandering others—these are written as offences.

In other words, failing to do what should be done, doing what should not be done, or being deficient in what should be done constitutes an offence.

There is also mention of a significant offence called poojya-pooja-vyatikramam, which seems to refer to negligence or indifference towards worshipping deities or venerating gurus.

The concept of aparadham must be understood in the context of the hierarchical codes of feudal languages. Attempting to study or discuss such matters through the English language will yield no understanding of Brahmin or Hindu concepts of dharma and adharma.

Although the Brahmin religion mentions sins in this manner, it is a remarkable achievement that the English administration in Malabar, without relying on any such spirituality or support, created a group of highly upright, incorruptible government officers—direct recruit officers—solely through the propagation of pristine English.

Though this officer class included people from various religions and castes, collectively, they observed, adhered to, and emulated only the behavioural codes and courteous communication practices of their English superiors.

Neither the Brahmin religion nor Hinduism succeeded in eliminating the hierarchical distinctions in this subcontinent. On the contrary, their doctrines of dharma and adharma reinforced such distinctions.

No religion seems to have succeeded in eliminating practices like government officers taking bribes, exploiting people with excessive salaries, treating them disrespectfully, or fostering intense personal enmity among people.

However, during the English administration in British India, the pristine English language was able to target these issues and quietly eradicate them without anyone noticing.

Quote: Never engage in sinful acts. End of Quote

Such writings may lead a person into a moral dilemma.

What constitutes a sin is a significant question in itself. It is understood that the English word for paapam (sin) is ‘sin’.

In Christianity, there is the concept of the Seven Deadly Sins, which are pride (arrogance), greed (avarice), lust, envy, gluttony, wrath, and sloth.

Similarly, acts considered sinful include homicide, abortion, infanticide, fratricide, patricide, and matricide.

There are other sins as well, such as homosexuality, slavery, neglect, bigotry, and exploitation.

However, equally or even more severe than these is the unpardonable sin of blasphemy against the Holy Ghost, or Yahweh, or God, or God’s name.

It seems that sins in Islam may be somewhat similar, though I (this writer) lack the precise knowledge to confirm this.

Many of the sins mentioned above appear to be, to some extent, personal failings or weaknesses.

Others were defined as legal offences when the English administration enacted laws in this subcontinent. Thus, they may not strictly fall under the definition of spiritual sins.

Some sins were suppressed through social reform efforts and legislation by the English administration.

Consequently, the sin that religions most strongly oppose may be blasphemy against God or God’s name. It appears that the English administration did not address such sins, though I am not certain.

The sins relevant here are those defined as such in the Brahmin religion. It seems these should be based solely on the Vedas. However, today, in the Brahmin religion, or Hinduism, there is a tendency to label anything mentioned in various texts—written across different centuries over thousands of years with little connection to each other—as Hindu doctrine.

In that sense, any doctrine can be proclaimed as Hindu doctrine. There is little significance in this.

In the Brahmin religion, two concepts are evident: dharma and aparadham (offence).

As mentioned earlier, dharma may not have a strong connection with the English word ‘justice’ (fairness or righteousness). In the feudal language of Sanskrit, which socially and familially organises communities in a hierarchical structure, dharma likely refers to behaving in accordance with that structure, establishing personal relationships accordingly, and maintaining discipline in line with it.

It is somewhat akin to members of the Indian police forces behaving in a way that does not disrupt the hierarchical tiers of their institution.

Acting contrary to this would be adharma.

The concept of aparadham is similar.

Entering temples in vehicles or wearing footwear, not participating in festivals, not bowing before the deity, eating before making offerings, speaking loudly, turning one’s back, self-praise, or slandering others—these are written as offences.

In other words, failing to do what should be done, doing what should not be done, or being deficient in what should be done constitutes an offence.

There is also mention of a significant offence called poojya-pooja-vyatikramam, which seems to refer to negligence or indifference towards worshipping deities or venerating gurus.

The concept of aparadham must be understood in the context of the hierarchical codes of feudal languages. Attempting to study or discuss such matters through the English language will yield no understanding of Brahmin or Hindu concepts of dharma and adharma.

Although the Brahmin religion mentions sins in this manner, it is a remarkable achievement that the English administration in Malabar, without relying on any such spirituality or support, created a group of highly upright, incorruptible government officers—direct recruit officers—solely through the propagation of pristine English.

Though this officer class included people from various religions and castes, collectively, they observed, adhered to, and emulated only the behavioural codes and courteous communication practices of their English superiors.

Neither the Brahmin religion nor Hinduism succeeded in eliminating the hierarchical distinctions in this subcontinent. On the contrary, their doctrines of dharma and adharma reinforced such distinctions.

No religion seems to have succeeded in eliminating practices like government officers taking bribes, exploiting people with excessive salaries, treating them disrespectfully, or fostering intense personal enmity among people.

However, during the English administration in British India, the pristine English language was able to target these issues and quietly eradicate them without anyone noticing.

9. When a sepoy ranker masquerades as an officer

The next rite in the Shodasha Kriya is the marriage ceremony.

Before proceeding to it, I believe it’s worthwhile to briefly review the Shodasha Kriya ceremonies discussed thus far.

2.1 Garbhadhana ceremony

2.2 Pumsavana ceremony

2.3 Seemanthonnayana ceremony

2.4 Jatakarma ceremony

2.5 Namakarana ceremony

2.6 Nishkramana ceremony

2.7 Annaprashana ceremony

2.8 Chudakarma ceremony

2.9 Upanayana ceremony

2.10 Vedarambha ceremony

2.11 Samavartana ceremony

The Garbhadhana ceremony involves a husband and wife uniting sexually to create a new individual in their lineage. Both must think and act with great social and mental elevation, upholding higher moral values than the lowly Pariahs residing around their household, in preparation for this rite.

It is clear that the aim is to embed lofty numerical values into the transcendental software codes of the mind, thoughts, emotions, and experiences.

Each subsequent ceremony strives to instill these lofty numerical values into the transcendental software codes of the child, whether yet to be born or already born.

The pregnant woman’s diet, sleep, thoughts, words, interactions, things heard, seen, closely observed, and scents smelled must all fill the transcendental software codes of her mind and body with elevated values. By hearing and contemplating words associated with sanctity and positive values—such as cows, wealth, longevity, and fame—the growing individual in the womb is imbued with these lofty values to the greatest extent possible.

Once the child is born, a firm belief must take root in their mind and body that they are a divine individual, distinct from the lowly Pariahs of varying standards living around the household. This fosters immense self-confidence, both socially and in communication. The words used by the lowly Pariahs must undoubtedly reflect the child’s superior status.

The child must hold an unshakable conviction, like a rock, that they are “highest he/she” (Oru), while the lowly Pariahs, regardless of their age, are merely “lowest you” (Nee/Inhi).

When naming the child, the name should proclaim their divinity to others. Names drawn from the illustrious deities of ancient, radiant mythology are ideal, as they may evoke sublime rhythms in the listener’s mind. Conversely, names carrying the taint of lowly origins will degrade the listener’s perception, dragging the word codes steeply downward.

Through observing nature, vast knowledge enters the inner chambers of the child’s imagination, born of noble lineage. The boundlessness of the universe and the verdure of nature may fill the individual with profound mental tranquillity, presence, and equanimity.

The first feeding of the child is celebrated as a grand occasion, further proclaiming the individual’s supreme importance to the lowly Pariahs.

The next rite is the Upanayana ceremony, the receiving of the sacred thread. In those days, this was akin to a young man from a prominent household passing the IAS/IPS examination and heading for training—an experience that left an impression on the lowly Pariahs around the household.

Following this, Vedic studies and learning in a gurukul take place. Afterwards, the young Namboodiri returns to the household.

This is comparable to returning home after IPS training, adorned with insignia of authority on shoulders, sleeves, and head. Everyone in the governmental hierarchy and ordinary people alike recognise this individual as someone with great authority. They will only use words that reflect this status.

It is evident what these Shodasha Kriya rituals aim to achieve. The commitment begins even before the child’s birth to create an individual of great elevation. However, the goal is not to create a genius or an extraordinary talent. Instead, it is to craft an individual with the firm conviction of their own superiority, free from any intellectual shortcomings or flaws.

Such an endeavour cannot be unilateral. Merely possessing this conviction of superiority is insufficient. If this mindset exists only within the individual, others may perceive it as delusion. There must be a group of people around who are willing to acknowledge their own subservience, maintain an inferior mindset, and offer their loyalty.

It is clear that the inspiration for implementing such Shodasha Kriya practices comes from the feudal language codes prevalent in society, which create hierarchies of the elevated and the lowly Pariahs. Without the existence of the lowly, such arduous efforts would lack relevance.

A primary purpose of these rituals and actions is to convince the lowly Pariahs that the individual, through language codes, is of a superior status.

This is a common feature in all feudal language movements.

In the Indian Army, officers are established as a highly divine class through various symbols, such as insignia, small flags, codes of conduct, the use of high-end liquor brands, derogatory language toward subordinates, exclusive mess halls for officers, private spaces for them and their families, exclusive evening banquets, and designated playgrounds. These maintain immense respect and subservience among ordinary soldiers.

While unwritten rules require officers to converse in English among themselves, there is an explicit or implicit rule prohibiting them from speaking in English with ordinary soldiers.

If ordinary soldiers mimic the officers’ behaviour, it may seem impressive to see or hear, but the question remains: what are they trying to achieve or convey?

Decades ago, an individual who retired from the army at an ordinary rank and became a Malayalam writer reportedly wrote a story about the military. In it, a young man from the hair-cutting section, recently married, returned with his youthful bride. His middle-aged supervisor reportedly convinced him to occasionally act like officers.

This is considered a bold endeavour, as everyone knows it involves living, even briefly, in the same mindset as the officers who dominate and suppress them with feudal language codes—a mentally exhilarating experience.

Thus, these two would occasionally dress up as officers at night. The middle-aged supervisor had convinced the young man that officers share their wives. Consequently, during these role-playing sessions, the supervisor would take possession of the young man’s youthful wife.

It is unclear how the story concluded. However, it is rumoured that the Indian Army subjected the writer to various difficulties.

This story is noted here because it seems the Brahmins performed the Shodasha Kriya rituals to shield their people from the derogatory language of the lowly Pariahs around them and to instil in their individuals a sense of immense superiority over these lowly people.

The notion that today’s lowly communities, now claiming to be Hindus, perform such acts is akin to ordinary soldiers playing at being officers.

This is because it is unclear what negativity the Shodasha Kriya rituals aim to rise above or avoid. Historically, Brahmins viewed these very communities as embodiments of negativity. The question arises: what harsher negativity are they trying to shield themselves from?

The next consideration is how an individual from a lowly community can protect their son or his daughter from the pervasive negativity surrounding and within them, and what kind of shield can be used to set them apart.

I plan to write about this in the next piece.

10. The aura of personality beyond divine individuality

Feudal languages shape a social ladder, with each person standing on its various rungs as part of the structure itself. This ladder is an element of the framework that designs the societal form.

If we consider this depiction more intricately, we can imagine that within this same framework, there exist numerous such ladders, and an individual can simultaneously occupy different rungs on multiple ladders, maintaining a presence across them.

However, before the English administration raised its flag in this subcontinent, individuals could only ascend a limited number of distinct ladders. The king, local chieftains, landlords, temple dwellers, Nairs, and the lowly Pariahs of various levels beneath them—each person within these groups typically had a presence on just one or two ladders: one in their occupational role and another in their family.

It was with the advent of the English administration that individuals began to engage in various domains based on their multifaceted abilities, participating at different levels in each. Prior to this, both the prominent and the lowly in society were confined to extremely narrow spatial limits.

The issue lies in the servility expressed and extracted under the guise of ‘respect.’ This notion of respect, with its manipulative nature, emerged when an uneducated linguistic group ascended to social heights in this subcontinent. This freed everyone, previously entangled in invisible chains, from societal constraints. They gained the ability to climb any ladder of their interest.

Now, let us consider a depiction crafted purely from imagination.

In Malabar, there is a young man from the socially lowly Pariahs—perhaps a Cheruman, Pulayan, Pariah, Malayan, Mala Arayan, Makkathayi Thiyyan, or Marumakkathayi Thiyyan, belonging to any such group. This individual comes from a family of low status, meaning they lack wealth, familial prestige, or official connections of high standing.

The harsh traits inherited from their lowly Pariah status were clearly visible in this person’s family—evident in their facial expressions, body language, behaviour, and stunted physical development.

Yet, this individual was distinctly different from their community in a particular way. Before elaborating on that, let me explain further.

Professionally, this person had risen considerably above the standard of their community. Subsequently, he married. His wife’s family shared the same social and cultural standing as his own. The couple had a child.

Now, let me describe the difference in this individual. From a young age, he had direct and indirect exposure to a refined English atmosphere. He had access to numerous English children’s literature, classical literary works, and comic books. Additionally, he had the opportunity to watch old English films.

This precise, subtle, yet profoundly transformative exposure shaped his mind, setting it apart from the mental standards of his family and community.

However, these internal changes were not necessarily apparent to a casual observer. This is because he was born, raised, and communicated in the local feudal language. Moreover, he grew up enduring the harsh suppression of word codes from socially inferior family members, societal overlords, and officials.

To outward appearances, this person bore the persona of a lowly Pariah, but within burned a mastery of English knowledge and proficiency at the highest level. This was not immediately evident to others. His English proficiency was not merely at the level of spoken English. Rather, it was at a level where, having read numerous classical English literary works, he could vividly imagine the social atmosphere of old England.

If spoken English proficiency is likened to the heights of the Sahyadri mountains, the level represented by classical English literary works is akin to the peaks of Mount Kailasa itself.

This person recognised the many positive qualities of the English language. He desired that his son also benefit from the qualities of an English linguistic atmosphere.

Yet, he was deeply aware that this alone would yield no significant benefit.

His lowly Pariah status and family ties, through feudal language codes, would impose a heavy burden and downward pull on his son’s mind. While government job reservations might secure high-ranking government positions for his son, his focus was not on the social elevation such jobs provide. Instead, he aimed for an almost impossible goal: to free his son’s personality from the mental traits of the lowly Pariahs and to entirely reshape him.

He understood that the label of being a child of the lowly Pariahs would be imposed as a social burden on his son through the blows of local language codes.

Yet, he also had the insight that this burden came not only from the upper echelons of society but also from himself, his own kin, his caste’s neighbours, and, moreover, from the teachers at the government school near their home, where his son was legally required to study, through their word codes.

The knowledge that high-ranking Namboodiris of old protected their children from such oppressive word codes and created a shield to deny their entry through the Shodasha Kriya ceremonies is indeed profound.

However, would replicating the rituals performed by the Namboodiris, treating them as customs, lead his son to be recognised as a divine individual in the eyes of his lowly Pariah family, neighbours, community, schoolteachers, and schoolmistresses?

If so, it could be understood that the Shodasha Kriya rituals possess a magical power. But his goal was not to make his son a divine individual!

It requires no great education to realise that thinking the Shodasha Kriya rituals could transform a lowly Pariah into a divine individual is sheer folly. For a lowly Pariah like him to expect great benefits from such actions is akin to the foolishness of an ordinary Indian Army soldier masquerading as an officer. Within the societal framework, each individual has a clearly defined position and status.

Performing many of the Namboodiris’ Shodasha Kriya rituals might facilitate a family gathering, but this person did not believe it would bring about the mental transformation he sought in his son. This was because the mental elevation he aimed for had no connection to the divinity targeted by the Shodasha Kriya rituals.

Nothing done within the societal framework would yield the mental liberation he sought.

What must be done is to step outside the societal framework and take strides toward the goals he envisioned.

11. The all-pervasive framework entrenched in the feudal language nation

Living outside the framework of the surrounding society and nation, in a manner contrary to its social structure, is almost entirely impossible in feudal language regions. Individuals gain a slight degree of freedom and a state of detachment from the rigid bonds of personal relationships only in pristine-English regions. However, even there, this may be unattainable for most beyond a certain limit.

In feudal language regions, individuals are tightly bound by harsh yet invisible strings.

It’s easy to say, “he (ayaalkku) could have done it this way,” “he (ayaalkku) could have spoken to him (Oru) like that,” or “he (ayaalkku) could have entered there at that moment,” but invisible strings hold each individual back, pulling and pushing them in various ways. Some invisible doors remain closed to him (ayaalku), while others stand open.

While such dynamics may exist in English as well, compared to feudal languages, they seem far gentler and less rigid.

The lowly Pariah individual with exceptional proficiency in English, mentioned in the previous piece, is striving to raise his son, freeing and detaching him from the invisible strings that could entangle him.

This young man’s endeavour requires extraordinary determination, purpose, discernment, and a mental outlook that transcends the lowliness of his surroundings, underpinned by profound proficiency in the English language. Financial security and independent sources of income could provide the economic energy needed to support such an undertaking.

In feudal language nations like India, the most prominent social and political framework is that of the government officialdom. Though often described as having the veneer of a welfare state, in this country, it is essentially an extortion organisation. It operates based on the collective interests of its members and the personal ambitions of each individual within it.

This framework exists as a vast structure, extending from top to bottom. Those outside it, standing beneath or near some level of it, secure whatever benefits, advantages, profits, or gains they can by grovelling, flattery, sycophancy, servitude, or bribery.

Each individual has a clearly defined position and status within this framework, with the elevated and the lowly Pariahs distinctly placed. By leveraging various mechanisms within this framework, individuals can move upward or downward within it. Competitive examinations leading to prestigious government jobs or commercial successes through various enterprises often facilitate upward mobility.

What binds individuals within this framework, indicates their relative rise or fall, and defines their status are the Indicant word codes of the feudal language. Family prestige, government employment, other occupations, caste-based hierarchies, and ownership of landed property can all influence these Indicant word codes.

Alongside this framework, other structures coexist, intertwined and interdependent, such as joint families, nuclear families, commercial enterprises, and educational institutions.

An individual who stands outside this vast framework or refuses to live subject to its controls and conventions is, in the eyes of the framework, a smouldering spark. This spark is indeed a troublemaker. Thieves, rogues, or robbers do not qualify as such sparks, as they operate within this vast framework.

The smouldering spark referred to here is someone unwilling to conform to the framework’s structure—not a thief, rogue, or any such miscreant.

If this framework were honest, free of deceit, hypocrisy, or bias, and treated individuals without discrimination, then this smouldering spark would indeed be a culpable miscreant. However, the framework in this nation stems from the extortionist organisation of government officialdom.

Thus, a smouldering spark standing apart from this framework need not be a wrongdoer. This person is neither a coward, a wielder of firearms, a murderer, nor an instigator of murder.

The young man referenced in this piece intends to raise his son free from the pervasive framework entrenched across this nation, liberated from its myriad constraints and pulls.

In old English nations, such an intention might not be overly challenging. However, the need for such an endeavour in those regions may be quite limited.

This is because their social framework does not resemble a sprawling vine climbing a towering wall rooted in society’s soil. Instead, society is like a flat canopy of diverse vines, with individuals largely free yet collaboratively sharing benefits in various ways.

The young man’s desire to free his son from the entrenched framework of this nation stems from the silent, overflowing mental inspiration and vibrant enthusiasm provided by the pristine-English language. However, as this is an English-inspired enthusiasm, it may not manifest in loud outward displays.

The English language exemplifies silent preparation, immense strength, and a powerful will poised to surge forth.

12. Strategies to chain down those standing outside the framework

Creating a miniature old England in Malabar, or reviving a bygone British-Malabar, may fall under the category of humanly impossible endeavours.

However, the lowly Pariah individual from Malabar, with profound proficiency in the English language, mentioned in this piece, is not attempting such feats. Instead, he (Oru) strives to break free from the pervasive, yet invisible, framework that grows like a sprawling vine from bottom to top in this nation, aiming to forge a new individual with an independent existence and personality.

Ironically, this new individual would, in reality, align with the rules, codes of conduct, and interpersonal norms outlined in the Constitution, which is written in English and grants citizens personal freedoms and dignity.

When translated into feudal languages, the Constitution seems to transform into a foolish document.

The framework entrenched across this nation starkly contradicts the principles enshrined in the Constitution. I won’t delve into that issue now.

The most critical step to liberate his son from this pervasive national framework is to avoid teaching him local feudal languages and to prevent others from communicating with him through such languages.

It’s uncertain whether readers grasp the depth of this point. Language encodes all manner of interpersonal codes, behavioural norms, provocations, ideas, beliefs, superstitions, obligations, subservience, standing in respect, or insulting by not standing, and more. Similarly, the arrogance of the officialdom, including the police department’s fearsome and repellent nature, stems from feudal language codes.

Translating these elements from one South Asian feudal language to another yields little change. However, translating rules, codes of conduct, and rights into pristine-English erases or renders unnecessary many forms of subservience and servility.

In other words, when an individual operates or behaves with an English-language mindset in feudal language settings, it may often be perceived as defiant by others.

The lowly Pariah individual mentioned here, by not teaching his son the local feudal language or allowing him to understand it, may create a situation where surrounding institutions and individuals cannot impose their personal strings, subservience, definitions, restrictions, or lowly mental attitudes on this growing individual.

While roles like elder brother, elder sister, uncle, aunt, younger brother, younger sister, teacher, pupil, political leader, government office peon, clerk, senior official, policeman, police officer, employer, worker, agricultural labourer, or toilet cleaner exist in English, these positions do not significantly alter word codes.

In contrast, in feudal languages, these roles require expressing subservience or dominance through prescribed word codes when interacting with others. Failing to show subservience where required may lead others to view the individual as ill-mannered or insolent. Conversely, failing to assert dominance or demean where expected may result in being seen as incompetent or worthless.

The English language creates mental states that defy such definitions, tailored to its unique requirements. Thus, thinking in English while behaving in feudal languages creates issues.

Namboodiris, through Shodasha Kriya ceremonies, aim to place their children at heights untouchable by the harsh, negative social strings around them. Yet, they do so within the societal framework, positioning themselves and their children at its apex, shielded from demeaning relational strings.

In contrast, the lowly Pariah individual here seeks to place his son outside the societal framework, neither above nor below anyone. This is intolerable to surrounding feudal language speakers.

When Namboodiris elevate their children, others can offer subservience, as language codes create such a mental state in all. However, those standing outside the societal framework—especially the son of a lowly Pariah—are not permitted to remain detached. This poses a problem for those at society’s heights, teachers, schoolmistresses, government office workers, police, neighbours, lowly Pariahs, and indeed, everyone.